The Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) is considered ancient Egypt's Classical Age during which it produced some of its greatest works of art and literature. Scholars remain divided on which dynasties constitute the Middle Kingdom as some argue for the later half of the 11th through the 12th, some the 12th to 14th, and some the 12th and 13th.

The 12th Dynasty is often cited as the beginning because of the vast improvement in the quality of art and architecture but these developments were only possible because of the stability the 11th Dynasty secured for the country. The most commonly accepted dates for the Middle Kingdom, then, are 2040-1782 BCE, which include the latter part of the 11th Dynasty through the middle of the 13th Dynasty.

The 13th Dynasty was never as powerful or stable as the 12th and allowed an immigrant people known as the Hyksos to gain power in Lower Egypt, which eventually grew strong enough to challenge the authority of the 13th Dynasty and usher in the era known as the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782-c.1570 BCE). According to every estimation of the Middle Kingdom, Egypt reached its highest point of culture during the 12th Dynasty, and the innovations of this period influenced the rest of Egypt's history.

Designations such as 'Middle Kingdom' and 'Second Intermediate Period' are constructs of 19th century CE Egyptologists in their attempt to make more manageable the long history of the country. The ancient Egyptians themselves used no such names for their eras in history. Those periods which are marked by the country's unification under a strong central government are called 'kingdoms' while the times of disunity or long-term political or social unrest are known as 'intermediate periods.' Each of these eras has their own defining quality, including the Middle Kingdom, but scholars have claimed this period is more difficult to connect to any central image or accomplishment. Mark van de Mieroop comments on this:

While both the modern term 'Middle Kingdom' and the ancient presentation of [it] may suggest that this period parallels the Old and New Kingdoms, in many respects it is more difficult to define the Middle Kingdom than those other periods. In simplistic terms we can point to the pyramids as the Old Kingdom's defining characteristic and at the empire for the New Kingdom; no comparable single feature describes the Middle Kingdom. It was a period of transformation. (97)

It could be argued, however, that the physical evidence of that transformation is the defining characteristic. The literature and art of the Middle Kingdom are unlike any that came before it and influenced everything which followed after. Even though the Middle Kingdom may not have the grand pyramids of Egypt's past or the power which lay in the future, the contributions made by this era contributed enormously to the definition of Egyptian culture as it is recognized in the present day.

Influence of the First Intermediate Period

The Middle Kingdom rose following the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE), a time when the central government was diminished almost to the point of non-existence and the regional administrators (nomarchs) governed their districts (nomes) directly until two kingdoms developed - Herakleopolis in Lower Egypt and Thebes in Upper Egypt - out of minor provincial cities and challenged each other for supreme rule of the country.

Under the prince Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) the rulers of Herakleopolis were defeated and Thebes became the capital of Egypt. Mentuhotep was praised as a "second Menes" in reference to the first king of the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150-2613 BCE) who initially united the country.

Although the Middle Kingdom rulers tried to emulate those of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, and scholars have traditionally represented the Middle Kingdom as a return to the earlier paradigm, the political and social structure of the era was quite different. The First Intermediate Period had introduced a level of wealth and independence to the districts of Egypt which had not existed in the Old Kingdom structure of a supremely powerful centralized government, and when that era ended with Mentuhotep II's reunification, those changes in the culture remained. Although the king was again the ruler of all Egypt, subordinate officials often lived and acted like small kings and there was an ease in upward mobility in the society which had not existed before.

These changes from the First Intermediate Period are most clearly seen in the art and literature of the 12th Dynasty, which gives the Middle Kingdom its epithet of 'Classical Age.' The influence of many different districts of the country is seen in the architecture, written works, inscriptions, paintings, and tombs of the 12th Dynasty clearly indicating that regional influences were welcomed and respected and that artistic expression was more fluid at this time. The works of the Old Kingdom were commissioned and controlled by the royalty and are uniform in appearance and style, while those of the Middle Kingdom are much more varied. None of these changes could have come about, were it not for the transitional era known as the First Intermediate Period.

The First Intermediate Period & the Rise of Thebes

After the collapse of the Old Kingdom following the 6th Dynasty, there was no strong central government in Egypt. This came about, in part, because of the great works commissioned by the kings of the 4th Dynasty who built the pyramids at Giza. King Sneferu, the first ruler of the 4th Dynasty, initiated the construction of pyramids and set the paradigm of diverting resources and manpower to building mortuary complexes. His successors Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure (the builders of the Giza pyramids) followed his example, but it is no accident that the pyramid of Khafre is smaller and his complex less luxuriant than Khufu's Great Pyramid or that Menkaure's is smaller than Khafre's. The enormous resources required for these projects ran out as the Old Kingdom went on.

It was not just a problem of what it cost to build the pyramid complexes but also a matter of maintaining them. The maintenance was left to the priests of the complexes and the local official, the nomarch, of the region, who received money from the royal treasury. As more money went to the districts from the capital at Memphis, those districts naturally increased in wealth, and with the rise in popularity of the Cult of the Sun God Ra, the priests gained more wealth and power. This situation, combined with others of the time, brought about the end of the Old Kingdom.

During the First Intermediate Period, these nomarchs who now had the power to control their own districts without regard for Memphis essentially became kings of their regions. They passed and enforced laws and gathered taxes without consulting with the kings who still tried to rule from the old capital. The diversity of the regions of Egypt at this time can be seen in the art and architecture which express each separate district's individuality.

Thebes, at this time, was a minor city on the banks of the Nile which had no more prestige than any other. The kings of Memphis moved their capital to Herakleopolis, perhaps in an effort to gain more control over the larger population there, but remained as ineffectual as they had been in the old city. Around 2125 BCE a nomarch of Thebes named Intef challenged the authority of Herakleopolis and initiated a rebellion which set Thebes up as a rival to Herakleopolis. Intef's successors each gained more and more ground as Thebes grew in power and wealth. New and greater tombs were built and grander palaces until, with the ascension of Mentuhotep II and the defeat of Herakleopolis, Thebes became the capital of Egypt.

Mentuhotep II & the 11th Dynasty

Although Mentuhotep II became the 'second Menes' who united Egypt and ushered in the era of the Middle Kingdom, the path to that unification was initiated by Intef I and made clear by his successors. Mentuhotep I (c. 2115 BCE) followed Intef I's lead and conquered the surrounding nomes for Thebes, greatly enhancing its stature and increasing the city's power. His successors continued his policies, but Wahankh Intef II (c. 2112-2063 BCE) is credited with some of the most important steps toward unification in taking the city of Abydos and claiming for himself the title 'King of Upper and Lower Egypt.' Wahankh Intef II further strengthened the position of Thebes by ruling justly and commanding military expeditions against Herakleopolis, which weakened the Memphite king's hold on their region.

Mentuhotep II built on these early successes to finally defeat Herakleopolis and, afterwards, to punish those nomes which had remained loyal to the old kings and reward those which had honored Thebes. Once the process of unification was underway, Mentuhotep II turned his attention to governing, military feats, and building projects. Margaret Bunson writes:

The era that began with the fall of Herakleopolis to Mentuhotep II was an era of great artistic gains and stability in Egypt. A strong government fostered a climate in which a great deal of creative activity took place. The greatest monument of this period was at Thebes, on the western bank of the Nile, at a site called Deir el-Bahri. There Mentuhotep II erected his vast mortuary complex, a structure that would influence architects of the 18th Dynasty. The Mentuhotep royal line encouraged all forms of art and relied upon military prowess to establish new boundaries and new mining operations. (78)

Mentuhotep II's successor, Mentuhotep III (c. 2010-1998 BCE) continued his policies and enlarged their scope. He sent an expedition to Punt and fortified the boundaries of the north-eastern Delta. He was succeeded by Mentuhotep IV (c. 1997-1991 BCE) about whom little is known other than that he sent his vizier, a man named Amenemhat, on an expedition to quarry stones. His entire seven-year reign is silence, but he most likely continued the policies of his predecessors successfully because when Amenemhat succeeds him as king the country is flourishing.

The 12th Dynasty Begins

Scholars who claim that the Middle Kingdom only truly begins with the 12th Dynasty do so because of the reign of Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) and the culture his dynasty forged. His family would rule Egypt for the next 200 years, maintaining a strong, united country and interacting significantly with neighboring lands.

When Amenemhat was vizier to Mentuhotep IV and was sent with his expedition to quarry stones for the king's project, he ordered an inscription made of amazing events which he experienced. First, a gazelle gave birth on the stone which had been chosen for the lid of the king's sarcophagus, signifying that stone had been chosen rightly as it was blessed with fertility and life. Second, an unexpected rainstorm fell upon the party which, once it had passed, revealed a well large enough to water the entire party.

This inscription was later interpreted to mean that Amenemhat was chosen by the gods to become king as the gods had clearly allowed him to experience miracles few others had. The later Middle Kingdom work Prophecy of Neferty enlarges on this idea by claiming to have been written before Amenemhat I's reign and "predicting" a king who will "come from the south, Ameny, the justified, by name" who will rule a united Egypt and smite his enemies.

Amenemhat I, for reasons not entirely clear, left Thebes and set up his capital and court at a city called Iti-tawi, south of Memphis. The exact location of the city is unknown but was probably near Lisht and was referred to in documents simply as the 'Residence.' The name Iti-tawi means "Amenemhat is he who takes possession of the Two Lands", according to van de Mieroop, and emphasizes the unity of Egypt (101). Amenemhat may have moved the capital to the Lisht region to distance himself from the previous dynasty - those who had united Egypt by force - and present himself as the unbiased king of the whole nation.

Lisht was close by the old capital of Herakleopolis and near to the fertile area of the Fayyum, and so placing the court of the king there would signal that this dynasty was not just Theban but open to all Egyptians. There seems to have been significant unrest at the court toward the end of his reign, and evidence suggests he was assassinated. His death and the succession which followed forms the backdrop for the famous Egyptian literary text The Tale of Sinuhe.

The Classical Age of the Middle Kingdom

Amenemhat I's successor was Senusret I (c. 1971-1926 BCE), who improved the infrastructure of the country and initiated the kinds of grand building projects which had characterized the Old Kingdom and represented the power of the king, including a temple to Amun at Karnak, which initiated the construction of the great temple complex there. Amenemhat I had followed the example of Wahankh Intef II and Mentuhotep II in granting power only to those most trusted in the family and limiting the power of the local nomarchs and priests.

One of the ways in which he curbed the nomarch's power was the creation of the first standing army. Prior to the 12th Dynasty, the Egyptian army was made up of conscripts raised by the nomarchs and sent to the king. Amenemhat I increased the power of the king by reforming the military so it was directly under his control.

Senusret I followed this same policy, which resulted in greater wealth and power for the throne and a stable central government. The bureaucracy of the 12th Dynasty was so efficient that, unlike that of the Old Kingdom, it kept wealth concentrated with the king but allowed for the growth and flourishing of individual districts without letting them grow too powerful. The king ruled all of Egypt, but individual officials were rewarded for their loyalty. Van de Mieroop writes:

All over Egypt local worthies announced their special status by erecting steles inscribed with biographies where they focused on their own achievements and, in many respects, this era shows the same cultural diversity as the preceeding period. (101)

The lack of tension between district officials and the crown allowed for great success in building projects, expansion of borders, defense, agricultural production, the improvements of cities and roads, and the development of art and literature. All of these improvements made Egypt one of the wealthiest and most stable countries in the world at the time. Margaret Bunson notes:

The 12th Dynasty kings raided Syria and Palestine and marched to the Third Cataract of the Nile to establish fortified posts. They sent expeditions to the Red Sea, using the overland route to the coast and the way through the Wadi Tumilat and the Bitter Lakes. To stimulate the national economy these kings also began vast irrigation and hydraulic projects in the Fayyum to reclaim the lush fields there. The agricultural lands made available by these systems revitalized Egyptian life. (78-79)

Senusret I began these policies by draining the lake at the center of the Fayyum through the use of canals. This not only made the fertile land of the lake bottom available for agriculture but freed up the water for easier access by more people. He is responsible for the White Chapel, a structure significant to archaeologists and scholars for listing all the nomes of the time on it.

The White Chapel was destroyed and recycled for use in the Temple of Karnak but restored between 1927-1930 CE and may still be seen today. Although the capital had left Thebes, the city was not neglected as construction of temples there - especially the great Temple of Karnak - continued throughout the Middle Kingdom and on into the New Kingdom.

Art in the Middle Kingdom

Artistic expression, although still employed for the glory of the king or the gods, found new subject matter during the Middle Kingdom. Even a cursory examination of Old Kingdom texts shows they were largely of a type such as inscriptions on monuments, pyramid texts, theological works. In the Middle Kingdom, although these kinds of inscriptions are still seen, true literature developed which dealt not just with kings or gods but the lives of common people and the human experience. Works such as the Lay of the Harper question whether there is life after death as does Dispute Between a Man and his Ba (his soul). The best known and most popular prose works such as The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and The Tale of Sinuhe also come from this period.

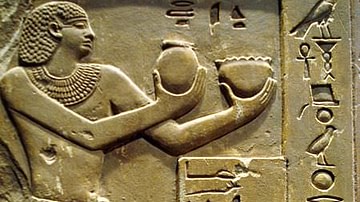

Sculpture and painting also often focus on daily life and common surroundings. Paintings of streams and fields, of people fishing or walking, are more common at this time. Images of everyday life and activities were painted in tombs so that the soul would be reminded of the life it had left behind on earth and move toward the Field of Reeds, the paradise of the afterlife, which was a mirror image of what had been left behind. Statuary became more realistic and new techniques were developed to create sharper and more life-like creations.

Temple building, following the great mortuary complex of Mentuhotep II at Thebes, worked to create a seamless relationship between the structure and the surrounding landscape which resulted in almost every temple built in the 12th Dynasty mirroring Mentuhotep II's to greater or lesser degrees. The kings of the 12th Dynasty encouraged this kind of expression and their cordial relationship with the local nomarchs made the 12th Dynasty one of the greatest in the history of Egypt.

The King & the Nomarchs

Senusret I was succeeded by Amenemhat II (c. 1929-1895 BCE) who may have ruled jointly with him. A distinctive feature of the Middle Kingdom is the practice of co-regency whereby a younger man, the king's chosen successor (usually a son) would rule with the king in order to learn the position and ensure a smooth transition of power. Scholars are divided on whether this practice was actually observed, although at points such as with Amenemhat II and his successor Senusret II (c. 1897-1878 BCE) there is no doubt. The practice of co-regency is suggested by double dates for two rulers on official cartouches but the meaning of those double dates is not clear.

Little is known of Amenemhat II's reign, but Senusret II is known for his good relations with the regional nomarchs and increased prosperity for the country. It is interesting to note that, under Senusret II's reign especially, the local officials prospered just as they had toward the end of the Old Kingdom and yet this did not cause the problems for the crown which it had before. Van de Mieroop writes:

The 12th Dynasty kings at Itj-tawi were powerful but they were not alone in possessing wealth and social standing. For a long time during the Middle Kingdom the provincial elites that had been more-or-less independent in the First Intermediate Period kept their local authority, albeit within a setting where a king ruled the entire country. (103)

These local officials were extremely devoted to their kings as evidenced by their biographies carved into tombs such as those at Beni Hassan (even though these are probably idealized). These tombs are all large and well-crafted, attesting to the wealth of their owners, and all were for nomarchs or other regional administrators, not for royalty.

Senusret III & Egypt's Golden Age

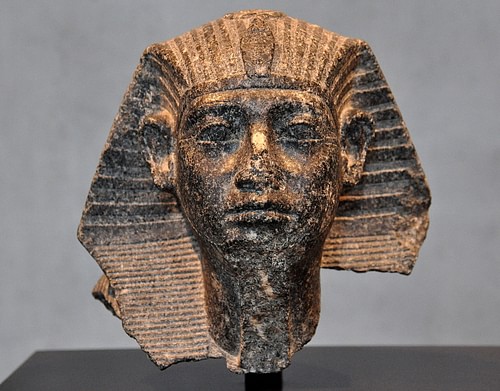

Senusret II was succeeded by Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE), the most powerful king of the era whose reign was so prosperous he was deified in his lifetime. Senusret III is considered the model for the legend of Sesostris, the great Egyptian Pharaoh who, according to Herodotus, campaigned in and colonized Europe and, according to Diodorus Siculus, conquered the entire known world. Senusret III is the best candidate as basis for Sesostris as his reign is marked by military expansion into Nubia and an increase in wealth and power for Egypt.

The prestige of the nomarchs declines during Senusret III's reign and the title vanishes from the official records suggesting the position was absorbed by the crown. This interpretation is supported by the institution of larger districts under the control of the central government. The individual families who had held the position do not seem to have lost their status, however, as the tombs at Beni Hassan mentioned earlier attest. Many of the biographies inscribed tell the story of a former nomarch who became a royal administrator devoted to the king.

Senusret III was the epitome of the warrior-king and embodied the Egyptian cultural value of military skill and decisive action. At the head of his army, he was considered invincible. His campaigns into Nubia expanded Egypt's boundaries and the fortifications he built along the border fostered trade. He also led an expedition into Palestine and afterwards increased trade relations with that region.

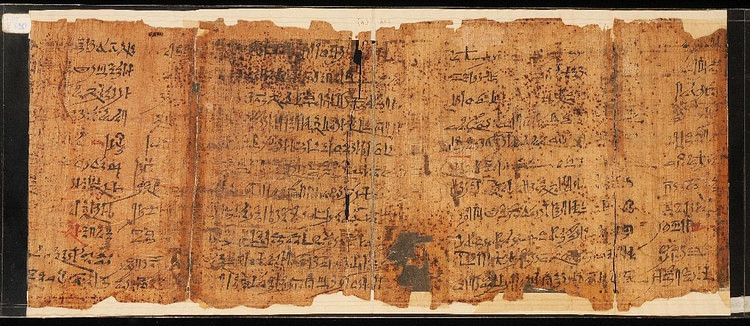

Although the Middle Kingdom was a stable time of great prosperity, one still finds evidence of uncertainty in the literature and other inscriptions of the period. The Lay of the Harper mentioned earlier, for example, questions the existence of an afterlife and encourages a more existential view. The Execration Texts, objects upon which spells were written to destroy one's enemies, are more numerous during the Middle Kingdom than any other period in Egypt's history. The Egyptians believed in sympathetic magic whereby one could elevate a friend, or destroy an enemy, by working with an object which represented them.

The Execration Texts were clay objects, sometimes statues, with the names of one's enemies written on them and a verse one would recite before smashing the object. As the piece was destroyed, so would one's enemies be. Senusret III's campaigns and military success assured the Egyptians of safety, but the number of these objects found during this period indicates that, as Egypt grew more secure and wealthy, the people grew more fearful of loss. The realism of the literature of the New Kingdom could be interpreted to reflect people's growing concern with the present, rather than an idealized afterlife, as their daily lives became more comfortable and they found they had more to lose than before.

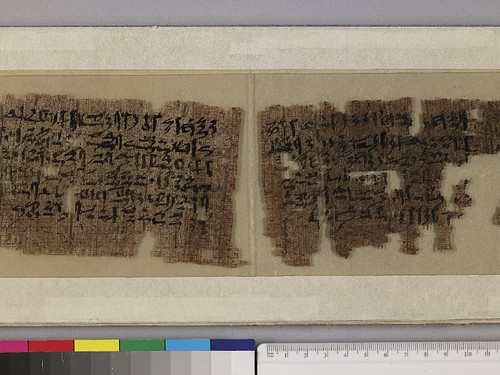

An example of this kind of fear can be read in the Ipuwer Papyrus (The Admonitions of Ipuwer) in which a scribe bitterly laments the loss of a golden age and the terrible conditions of the present. Although the Ipuwer Papyrus has been interpreted as history concerning the First Intermediate Period it is actually literature expressing the common human experience of a yearning for a golden age, a time when everything was beautiful, as contrasted to a present of uncertainty and fear.

The vivid images in the Ipuwer Papyrus convey clearly how times have changed for the worse which has encouraged a literal reading of it as referring to the First Intermediate Period, but the work makes more sense when read as an expression of fear of loss in the present, in the Middle Kingdom, and the kind of chaos which one should expect. The writer goes to great lengths to make sure the reality of such a loss is keenly experienced by the reader.

This fear of the loss of material goods, social stability - even all that one knew - could account for the rise in popularity of the Cult of Osiris at Abydos and the increasing veneration of Amun at Thebes. Amun combined the earlier aspects of the sun god Ra and the creator god Atum into an all-powerful god whose priests (like those of Ra in the past) would eventually amass more land and wealth than the pharaohs of the New Kingdom and would actually eventually topple the New Kingdom. Osiris, originally a fertility god, would become known as Lord and Judge of the Dead, the deity who determined where one's soul would spend eternity, and his cult would become the most popular, merging finally with that of his wife Isis.

Both of these gods promised stability in one's earthly journey and an eternal life beyond the grave. Senusret III paid special attention to the city of Abydos, where Osiris' head was thought to be buried, and sent representatives there with gifts for Osiris' statue. Abydos developed into a wealthy city during this time, the most popular place of pilgrimage in all of Egypt, with the most coveted necropolis. People wanted to be buried near Osiris to have a better chance of impressing him when their time came to stand before him at judgment.

At the same time, Amun's Temple at Karnak was continually being added to. This temple was dedicated to Amun, Lord of the Sky and Earth, who would become known as Amun-Ra, King of the Gods of Egypt. Amun assured believers of his constant watchful care during their lives and the continuation of harmony. The realism of the literary and artistic works of the time can be seen as reflected in the religious developments which promised an unbroken continuation of one's present life.

As the afterlife, presided over by Osiris, was seen as a direct reflection of one's present life, and one's present life was protected by Amun, one had no reason to fear change because there would be none. Death was only another change in the course of one's life, not the end of it. The depictions of the afterlife at this time became just as vivid and realistic as those of common scenes from everyday life.

The End of the 12th Dynasty

This realism even extends to how Senusret III is portrayed artistically. Whereas previous kings of Egypt are always depicted in statuary as young and strong, those of Senusret III are realistic and show him at his actual age and looking worn and tired from the responsibilities of rule. This same realism is apparent in the statuary of his son and successor Amenemhat III (c. 1860-1815 BCE), who is represented in statuary both ideally and realistically. Amenemhat III boasted of no great military victories but built almost as many monuments as his father and was responsible for the great mortuary temple at Hawara known as 'The Labyrinth,' which Herodotus claimed was more impressive than any of the ancient wonders of the world.

He was succeeded by Amenemhat IV (c. 1815-1807 BCE), who continued his policies. He finished his father's building projects and initiated many of his own. Military and trade expeditions were launched numerous times during his reign and trade flourished with cities in the Levant, especially Byblos, and elsewhere. The policy of the co-regency, if it was actually followed, which had ensured a smooth transition of power from ruler to ruler now failed in the case of Amenemhat IV who had no male heir to groom for success.

Upon his death the throne went to his sister (or wife) Sobekneferu (c. 1807-1802 BCE) about whose reign little is known. Sobekneferu is the first woman to rule Egypt since the Early Dynastic Period unless one accepts the queen Nitiqret (Nitocris) of the 6th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom as historical. The debate over the historicity of Nitocris has been going on for decades and is no closer to a resolution but many scholars (Toby Wilkinson and Barbara Watterson among them) now accept her as an actual person rather than a myth Herodotus created.

That aside, Sobekneferu reigned centuries before Hatshepsut, the woman often cited as Egypt's first female monarch, and to rule with full royal powers as a man. A woman named Neithhotep (c. 3150 BCE) and another, Merneith (c. 3000 BCE), are thought to have ruled in their own names and by their own authority in the Early Dynastic Period but these claims are contested. Merneith may have only been a regent for her son Den and Neithhotep, whose reputation as a reigning monarch relies largely on the grandeur of her tomb and inscriptions, could have simply been honored as a great king's wife and mother.

Unlike Hatshepsut, whose statues increasingly portray her as a male, Sobekneferu is clearly depicted as a female monarch. She either refurbished or founded the city of Crocodilopolis south of Hawara in honor of her patron god Sobek and commissioned other building projects in the great tradition of the other rulers of the 12th Dynasty.

When she died without an heir the 12th Dynasty ended and the 13th began with the reign of Sobekhotep I (c. 1802-1800 BCE). The 12th Dynasty was the strongest and most prosperous of the Middle Kingdom. As van de Mieroop notes, "All but the last two rulers of the 12th Dynasty built pyramids and mortuary complexes in the surroundings and filled them with royal statuary, relief sculptures, and the like" (102). The 13th Dynasty would inherit the wealth and the policies but would not be able to make any great use of them.

The End of the Middle Kingdom

The 13th Dynasty is traditionally seen as weaker than the 12th, and it was, but exactly when it began to decline is unclear because the historical records are fragmentary. Certain kings, such as Sobekhotep I, are well attested but they become less so as the 13th Dynasty continues. Some kings are only mentioned in the Turin King's list and nowhere else, some are named in inscriptions but not in lists. Manetho's king list, which is regularly consulted by Egyptologists, fails in the 13th Dynasty when he lists 60 kings ruling for 453 years, an impossible duration, which scholars interpret as a mistake for 153 years (Van de Mieroop, 107). The claim that the dynasty lasted for 150 years after Sobekhotep I is also probably wrong in that the Hyksos were firmly established as a power in Lower Egypt by c. 1720 BCE and were in control of that region by c. 1782 BCE.

The 13th Dynasty seems to have continued the policies of the kings of the 12th and kept the country unified but, as far as the fragmentary records indicate, none of them had the personal strength of the previous kings. Separate political entities began to spring up in Lower Egypt, the Hyksos being the greatest, and the capital at Itj-tawi does not seem to have had the resources to control any of them. Mortuary complexes, temples, and steles were still raised during this time and documents show the efficient bureaucracy of the 12th Dynasty was still in place but the momentum which propelled Egypt throughout the 12th Dynasty was lost.

As with the transition from the period of the Old Kingdom to the First Intermediate Period, the change from the Middle Kingdom to the Second Intermediate Period is often characterized as a chaotic decline. Neither of these characterizations is accurate. The 13th Dynasty faltered and a stronger power rose to take its place. Although the later Egyptian histories would characterize the time of the Hyksos as a dark period for the country, the archaeological record argues otherwise. The Hyksos, although they were foreigners, continued to respect the religion and culture of Egypt and seem to have benefited the country more than later historians give them credit for.

The Second Intermediate Period, during which the Hyksos ruled Egypt, may not have been the chaos it is presented as but still could not approach the heights of the Middle Kingdom. There was, in fact, some loss of culture such as that of hieroglyphic script and the rise of hieratic script. There is also evidence that artistic achievements were of a lower quality during the Second Intermediate Period. Scholars Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs write of the Middle Kingdom:

During its flowering, the Egyptian language attained a level of refinement that ever after made it the model for good prose in ancient Egypt. Art achieved an elegant realism: for the first time, pharaoh's faces were shown with lines of care and age, rather than idealized. Buildings, though not as mammoth as those of the Old Kingdom, possess a refinement that makes them second to none. Egypt also mounted serious military expeditions into the Sudan, forays that would later extend throughout the Middle East. Even a thousand years later, Egyptians looked back on the Middle Kingdom as a glorious time. (25)

The fear of loss evident in the texts of the Middle Kingdom was realized with the dissolution of the 13th Dynasty and the coming of another period of disunity and uncertainty. Later Egyptian writers would contrast the Middle Kingdom with the supposed lawlessness which preceded and succeeded it and raise it to the status of a golden age. The achievements of the period, especially of the 12th Dynasty, are undeniable and would continue to elevate the culture of ancient Egypt for the rest of its history.