The imperial Ming Dynasty ruled China from 1368 to 1644. It replaced the Mongol Yuan dynasty which had been in power since the 13th century. Despite challenges from abroad and within, the Ming dynasty oversaw an unprecedented growth in China's population and general economic prosperity. The Ming were succeeded by the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

Notable achievements of Ming China included the construction of the Forbidden City - the imperial residence in Beijing, a blossoming of literature and the arts, the far-flung explorations of Zheng He, and the production of the timeless blue-and-white Ming porcelains. Eventually, though, the same old problems that had beset previous regimes bedevilled the Ming emperors: court factions, infighting, and corruption, along with government overspending and a disenchanted peasantry which fuelled rebellions. As a consequence, the economically, politically (and some would say morally) impoverished Ming could not resist the invasion of the Manchus who established the Qing dynasty from 1644.

Collapse of Mongol Rule

The Ming dynasty was established following the collapse of the Mongol rule of China, known as the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). The Yuan had been beset by famines, plagues, floods, widespread banditry, and peasant uprisings. The Mongol rulers also squabbled amongst themselves for power and failed to quash numerous rebellions, including that perpetrated by a group known as the Red Turban Movement led by a peasant called Zhu Yuanzhang (1328-1398). The Red Turban Movement, an offshoot of the radical Buddhist White Lotus Movement and initially reacting against forced labour on government construction projects, was most active in northern China, and Zhu took over their leadership in 1355. Zhu also replaced the Red Turban's traditional policy aim of reinstating the old Song dynasty (960-1279) with his own personal ambitions to rule and gained wider support by ditching the anti-Confucian policies which had alienated the educated classes. Alone amongst the many rebel leaders of the period, Zhu understood that to establish a stable government he needed administrators not just warriors out for loot.

Zhu Yuanzhang as Emperor

Zhu Yuanzhang's first major coup had been the capture of Nanjing in 1356. Zhu's successes continued, and he defeated his two main rival rebel leaders and their armies, first Chen Youliang at the battle of Poyang Lake (1363) and then Zhang Shicheng in 1367. When Han Lin'er died - he who had claimed to be the rightful heir to the line of Song emperors - Zhu was left the most powerful leader in China, and he declared himself emperor in January 1368. Zhu would take the reign name Hongwu (meaning 'abundantly marital') and the dynasty he founded Ming (meaning 'bright' or 'light'). The Hongwu Emperor (aka Ming Taizu) would reign until 1398, and his successors continued his efforts to unify China through a strong centralised government and so consolidate the Ming dynasty's grip on power. A new and draconian law code was compiled (the Da Ming lü or Grand Pronouncements); dissenting officials were ruthlessly punished or executed; the Secretariat, which had acted as a bureaucratic limit on an emperor's power, was abolished; land and tax obligations were meticulously registered; provincial governments were reorganised with imperial family members placed at their heads; hereditary military service was imposed on the peasantry in threatened regions; international trade was curbed as all things foreign were considered a threat to the regime; and the old tribute system required of neighbouring states was revived.

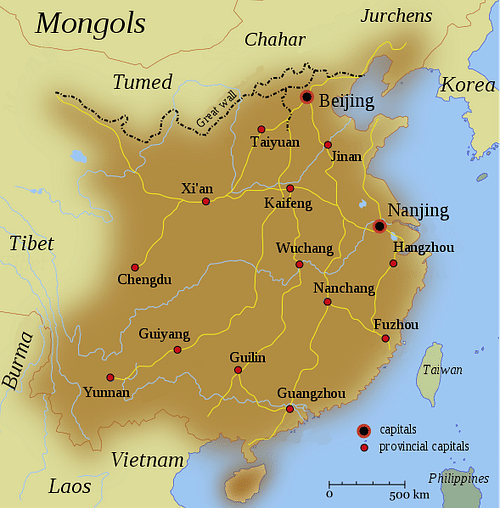

In the early 15th century the Mongols experienced a resurgence on China's borders and so Emperor Yongle (aka Chengzu, r. 1403-1424, the second son of Hongwu who had taken the throne after a three-year civil war) moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing in 1421 to be better placed to deal with any foreign threat. At huge expense, Beijing was enlarged and surrounded by a 10-metre high circuit wall measuring some 15 kilometres in total length. Such was the city's need for food, the Grand Canal was deepened and widened so that grain ships could easily reach the capital. The Great Wall of China was also repaired to better defend the northern frontier. The Ming, though, would greatly benefit from the divisions within the Mongol state - generally split into six competing groups which limited attacks to sporadic and half-hearted invasions rather than a concerted effort to restore China to the position it found itself under the Yuan. The Mongols did briefly besiege Beijing in 1449 but the city stood firm and the invaders withdrew back to the steppe.

International Trade

The stability of the Ming regime and agricultural reforms allowed significant economic growth and an increase in international trade (now promoted again), especially from the 16th century. The emperors were initially a little old-fashioned in their trade policies, insisting that certain countries only use certain ports at certain times, but eventually these rules were relaxed, and East Asia became a melting pot of trading neighbours as well as attracting the Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese. Vast quantities of silver, in particular, came into China via Manila from European-controlled Peru and Mexico. In 1557 the Portuguese were even permitted a trading base of their own at Portguese Macao. This opening up of trade also helped deal with the rampant piracy that had been plaguing Chinese waters, now that the Ming invested in a naval fleet.

There were brand new products coming in from the New World, exotica like sweet potatoes, maize, tomatoes, peanuts and tobacco, some of which would be cultivated in areas of China not suitable for homegrown crops, thus greatly expanding food production and so, in turn, the population. Over the course of the dynasty's reign, the population of China would rise from 60-80 million to 150-200 million. As urban centres grew so women amongst the wealthier classes began to enjoy more freedom than previously. They were able to own businesses in their own right, trade as merchants, and make an independent living as an artist or dancer. Conversely, changes in inheritance laws meant women's right went backwards in that area. Widows, for example, could no longer inherit their husband's land and they were expected not to remarry.

The economic prosperity in Ming China would, in turn, create a boom in the arts as a richer class of gentry developed who had money to spend and a great desire to show off their appreciation of fine art to any visitors to their homes. Aesthetic tastes were not limited to the classical arts either as gardens became a popular way for the well-off to entertain guests and display one's culture. The walled gardens of Suzhou became particularly famous where specially chosen rocks, tended pine trees and bamboo, pavilions, and walkways were all arranged to create a harmonious imitation of the scenes seen in landscape paintings by such renowned artists as Shen Zhou (1427-1509) and Dong Qichang (1555-1636).

Internal Problems

The Ming dynasty, despite its political success in the first half of the reign, eventually began to suffer the age-old problems that had beset every other regime in China through the ages. Intrigues perpetrated by the court eunuchs; abuses of power, and especially executions of those deemed guilty and their extended families, all usually carried out on a whim; a long line of talentless, ineffective, and often erratic rulers who spent more than they should have on grandiose building projects; factional fighting between ruling families; the ballooning of a parallel eunuch and civil service apparatus with each branch despising the other; and peasant revolts against incessant taxes and the harsh rule of often distant landowners all took their toll and weakened the Ming emperors' hold on power.

The dynasty was already in decline in the 16th century under Emperor Wanli (r. 1573-1620), especially when he withdrew from court affairs in 1582 following the death of his talented Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng, who had, more or less single-handedly, made the country's economic apparatus much more efficient and corruption-free. The power vacuum was willingly filled by the court eunuchs, and the economy took a nose dive following several hugely expensive wars against the Mongols and Japanese in Korea. In the 1620s a drop in average temperatures seriously affected crops, on top of which there was a wave of floods, then droughts, and widespread famine as a consequence.

In 1644 a rebel army led by Li Zicheng (1605-1645) attacked Beijing and, entering the city on 15 April, the last Ming emperor, Chongzhen (r. 1628-1644), hanged himself rather than be captured. On hearing the news of the capital's fall, the army commander Wu Sangui, stationed at Liaodong in north-east China, decided to allow a Manchu army - which had already fought Ming forces on several occasions in the past and was just then threatening to invade again - into China unimpeded in the hope they would put down the rebellion. As it turned out, despite some pockets of resistance from Ming loyalists, the Manchus established their own dynasty, the Qing dynasty and Li Zicheng was killed by peasants in 1645.

The Forbidden City

One of the lasting contributions to Chinese history made by the Ming emperors was the building of the Forbidden City in Beijing. Known in Chinese as Zijincheng ('Purple Forbidden City') and begun by the Yongle emperor from 1407, the complex was built as the imperial residence. The buildings were made of painted red wood and yellow ceramic roof tiles and surrounded by a high wall. Used also by the emperors of the Qing dynasty, the complex was continuously extended and restored until reaching its present impressive spread of some 7.2 square kilometres.

The buildings and their thousands of rooms are all carefully laid out in a plan which reflects the traditional Chinese view of the world. At the heart of the complex, on the most elevated site, is the Hall of Supreme Harmony, where imperial receptions were held. Other halls spread outwards from this central point, all built along a north-south axis. The emperor himself and all-male attendants lived in buildings on the eastern side while women lived on the western side of the complex. The Forbidden City also included government offices, all arranged strictly according to the rank of imperial officials. Needless to say, the forbidden aspect derives from the controlled access to it, with only officials of certain ranks and invited ambassadors being permitted within its walls. Today the complex contains the largest collection of imperial treasures and artworks in China.

Zheng He

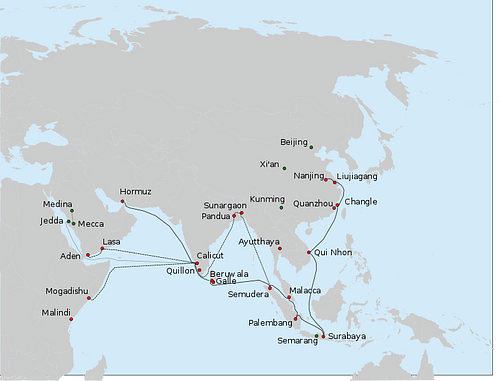

One of the enduring symbols of the Ming dynasty's eagerness to extend international relations is Zheng He (1371-1433), widely regarded as China's greatest-ever explorer. Born in Yunnan in southern China, Zheng was a eunuch Muslim who rose to become an admiral in the imperial fleet. The Yongle Emperor sent Zheng on seven diplomatic voyages between 1405 and 1433, with each voyage involving several hundred ships. Zheng would sail along established routes to the coast of India, the Persian Gulf, and the east coast of Africa, but many of his final destinations were new points of contact for the Chinese.

Zheng He's travels brought Southeast Asia into the sphere of the Chinese tribute system, but it was not successful in widening the system even further. Zheng did return to China with shiploads of valuable goods, although these did not generally meet the value of those goods shipped out in the first place (for example, silk, tea, and porcelain) and which were intended to woo foreign rulers into sending ambassadors to the imperial court in Beijing, principally to legitimise Yongle's rule and perpetuate the idea that the Chinese emperor was the greatest ruler on earth. Less tangible than wealth, Zheng certainly brought back plenty of knowledge of foreign lands and customs, and he did ship back such exotica as giraffes, gems, and spices.

Religion & Philosophy in Ming China

Neo-Confucianism continued to dominate in Ming China, as it had under the Song. The Chinese literati did generally become more questioning during the Ming, with such noted thinkers as Wang Yangming (1472-1529) who, influenced by Chan Buddhism, proposed radical new ideas. Wang believed that all people, even commoners, could develop their own innate knowledge of what is right through contemplation (as opposed to merely studying Confucian texts) and this would lead to the performing of actions which are right. Just what is 'right', of course, was open to debate, and the later thinkers of the Qing dynasty would cite such subjectivity as a reason for the moral decline they saw in later Ming times.

Buddhism, Taoism, and local cults continued to appeal to many, although they were less popular than Confucianism, even if Buddhist monasteries and monks grew in number during the supportive years of Hongwu's reign - the first emperor having spent a period of his childhood in a Buddhist monastery. One development in Buddhism during the Ming was the doctrine that one could arrive at Nirvana by doing good deeds and particular deeds were worth certain points. When one reached a total of 10,000 points, Nirvana would be reached. In general, as with Confucianism, there was thus a questioning of orthodoxy in all ways of thinking, which resulted in often radical new approaches, but these would have really only been seen, debated or followed by a minority of the scholarly class. These intellectuals had a forum for their views in the many independent academies which sprang up in the late Ming period, most important of which was the Donglin Academy, founded in 1604 and which survived into the 19th century.

What Were the Ming Dynasty's Cultural Achievements?

In 1370 the Ming reintroduced the traditional civil service examination system, which had been an essential path of social progression in pre-Mongol China and which would continue right into the 20th century. The Ming introduced a geographical quota system so that the richer regions did not, as was previously the case, dominate all the positions in the civil service. Meanwhile, the increase in the number of schools meant children with parents who could not afford private tuition could receive the essential education necessary to prepare for the exams. Success in these examinations required the study of Chinese classic literature which saw a revival in Confucianism after the Yuan.

There were several developments in Chinese literature in Ming China. Thanks to better printing presses, more books were printed than ever before, volumes were illustrated using woodblock prints to make them more attractive, and literature was itself made more accessible by being written in the vernacular language. There were books on how to live a good life, handbooks of etiquette, commentaries on classic texts, military treatises, notes for exam preparation, collections of woodblock prints, anthologies of poems, erotic works, and of course, fiction. Shuihuzhuan (about a group of well-meaning bandits), Xiyouji (about a priest who journeys to India to collect Buddhist scriptures), and Jin Ping Mei (a risqué satire of Ming government examining the life of a wealthy merchant) were all famous novels written in the vernacular during the Ming dynasty. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi), written in the 14th or 15th century and often attributed to Luo Guanzhong, remains to this day one of the most popular of all Chinese novels with its fantastic tales interwoven with historical figures during the fall of the Han dynasty and the beginning of the Three Kingdoms Period.

Scripts of the plays which travelling troupes performed were another popular source of reading. One of the most popular of all plays was The Peony Pavilion by Tang Xianzu (1550-1616). Written in 1598, it tells the story of a young woman who falls in love with a young man she only meets in dreams. The girl dies of loneliness and buries a portrait of herself in her garden. The young man of the dream then buys the house and finds the portrait, falls in love, and brings the girl back to life through the strength of his affections.

The Yongle Dadian was created during the reign of Emperor Yongle, a massive encyclopedia of all important Chinese literary works that had survived up to that point. The work, taking up over 22,000 chapters, was too large to be printed and, unfortunately, most of the original was lost in the strife at the end of Ming dynasty and that of a copy in a fire during the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901). Around 800 chapters of the encyclopedia do still exist in various libraries outside of China.

Ming Blue-and-White Porcelain

Finally, space must be allowed for the blue-and-white porcelain wares which have come to symbolise the Ming dynasty for many people today. Although artists of the Ming dynasty produced a wide range of pottery, it is this fine 'china' which was exported with unprecedented success. Actually made in earlier dynasties but perfected to new levels of craftsmanship under the Ming, porcelain - a hard, pure white, and translucent ceramic - was made at such noted centres as Jingdezhen and sold across China and to an appreciative world market which had not yet learnt the secret of making it. Porcelain was not just used to make vases and crockery but was shaped into all manner of goods from writing desk paraphernalia to bird feeders. The classic shapes and cobalt blue designs, which often used foliage motifs combined with landscape scenes inspired by scroll paintings, would be imitated around the world from Japan to Britain.