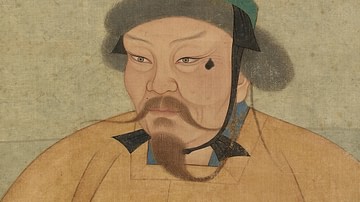

Mongke Khan was ruler of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE) from 1251 to 1259 CE. As the third Great Khan or 'universal ruler' of the Mongols, Mongke would oversee administrative reforms that continued to centralise government and ensure he had at his disposal the resources to successfully expand the empire further into China in the east and as far as Syria in the west. His reign was the last of the Mongol khans to oversee a unified empire before its definitive break-up into several khanates ruled by competing descendants of the man who had founded it all, Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE).

Genghis Khan's Descendants

In December 1241 CE Ogedei Khan died, having laid down the foundations for a governable empire that now spanned the whole of Asia. He was succeeded by his son Guyuk in 1246 CE after a brief stint as regent by Ogedei's wife Toregene. Guyuk's reign as the third khan of the Mongol Empire would last a mere two years. Guyuk had never been a popular choice, and many nobles, whose loyalties were divided amongst Genghis Khan's descendants, disputed the decision, hence the delay in his nomination after Ogedei's death. It is likely Guyuk was poisoned by a rival in 1248 CE and, perhaps not coincidentally, his death staved off a planned assault on the western part of the empire which had not supported his claim to the throne.

Once again, the empire's throne was empty and the descendants of Genghis Khan squabbled to see who would be the 'universal ruler' or Great Khan. A prime candidate was Mongke, born in 1209 CE the son of Tolui (c. 1190 - c. 1232 CE), the youngest son of Genghis Khan. Mongke had campaigned in southern Russia and eastern Europe with success along with other Mongol commanders from 1237 CE to 1241 CE. Specifically, he had been in command of that wing of the Mongol army that successfully attacked the Kipchaks (aka Cumans) north of the Caspian Sea. After his capture, the Kipchak chief Bachman refused to kneel before Mongke and so was cut in two pieces for his lack of obedience.

Mongke's candidacy for Great Khan was supported by Batu Khan, who represented the House of Jochi, This clan group had been headed by Batu Khan's father Jochi, the eldest son of Genghis Khan, but he had died in 1227 CE just before Genghis. Another impediment to this side of the family was that Jochi had been born while his mother had been in captivity and so his legitimacy as a true descendant of Genghis Khan was always disputed by other branches of the family. Perhaps for this very reason, Jochi's family had been given the lands in the far western part of the Mongol Empire but they remained the greatest rivals to the House of Ogedei, and the unruly Batu was the principal reason why Guyuk had been planning a campaign there.

Succession

Batu Khan had refused nomination for the position of Great Khan himself and preferred anyone except an Ogedei to rule the empire. Batu thus supported Mongke of the Tolui line. Batu was also grateful to Mongke's mother Sorghaghtani Beki for she had warned him of Guyuk's intention to campaign against him. Batu had established his domain around the Russian Steppe (mostly modern Kazakhstan and southern Russia), an area later given the rather romantic name the Golden Horde, which Batu ruled from 1227 to 1255 CE. In return for supporting Mongke's candidacy, Batu was given complete autonomy in his part of the empire.

After Mongke officially gained power at the kurultai meeting of Mongol tribal leaders in 1251 CE, he embarked on a ruthless purge of the House of Ogedei, the remains of which, represented by Qaidu II (1236-1301 CE), the grandson of Ogedei who was too young to be a threat, fled to set up permanent home in Siberia. The wife of the former khan Guyuk, Oghul Qaimish, who had served as regent (1248-1251 CE) following her husband's death, was one of the most infamous victims of the purge; tried for treason in December 1252 CE and then thrown into a river wrapped in felt - a fate usually reserved for witches. The House of Chagatai - another branch of Genghis' descendants - was similarly purged. Nobles and senior administrators across the empire were butchered by such imaginative methods of execution as trampling, cutting off the hands and feet, or filling the victim's mouth with stones. The wave of terror finally subsided and left the House of Tolui as the dominant clan group in the Mongol world.

Administrative Reforms

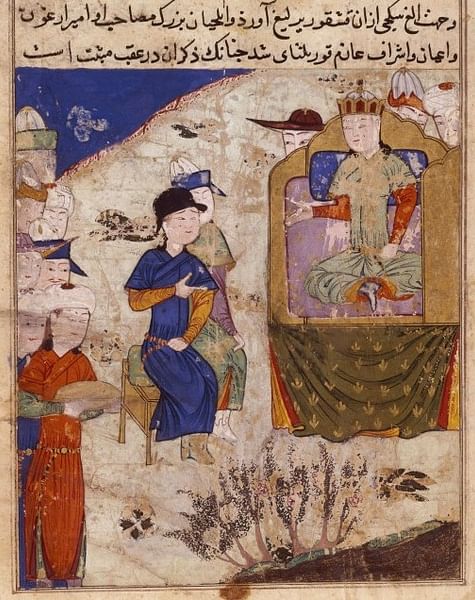

The Mongol Empire during Mongke's reign was described in detail in Itinerarium by William of Rubruck (c. 1220-1293 CE). The Franciscan missionary travelled to the capital Karakorum amongst other places, and the division of power between Mongke and Batu is reflected in the following quote from the Great Khan: "Just as the sun spreads its rays in all directions, so my power and the power of Batu is spread everywhere" (quoted in Morgan, 127). Rubruck also lamented that Mongke was frequently drunk whenever he was called to have an audience with the khan. The missionary was able to enjoy Mongke's court hospitality because many foreign representatives were welcomed there and there was no repression of any of the many religions practised in the empire - provided their adherents did not threaten the state. However, accounts in some sources that the khan converted to Christianity do not have any convincing evidence to support them.

Despite the bloody start to his regime, Mongke has been traditionally credited with instituting several important administrative reforms within the Mongol Empire, although many of these may, in fact, date back to the reign of Ogedei. Whoever was responsible, the general approach to government continued to shift from mere conquest and appropriating booty or imposing irregular taxes whenever required to properly governing an empire. Consequently, it was ensured that a prosperous sedentary community could provide a long-term and more constant revenue to the state via a fairer system of taxation. A census was ordered, new provinces included in the administration like those conquered from the Rus, and the government centralised. To help better regulate the tax system, from 1253 CE payments were made permissible in silver, silver coins, and silk as well as in the traditional kind (and furs in the Rus provinces and paper money in northern China were accepted, too). That all of these policies achieved their aim of enriching the state is evidenced in Mongke's ability to raise massive armies for campaigns on both sides of his empire.

Campaigns in Persia

Mongke made his younger brothers Hulegu (d. 1265 CE) viceroy (ilkhan) of Iran and Kublai viceroy of Mongol-controlled northern China. Each was given an army composed of two out of every ten soldiers in the empire (a scheme made possible thanks to the earlier census). From 1253 CE, Hulegu would mobilise and campaign in the west to successfully expand his domain in Iran and Iraq, crushing the troublesome Ismailis, otherwise known as the Assassins on the way in 1256 CE (who nobody liked for their heretic religious views and their penchant for assassinating people). More victories followed and eventually Hulegu defeated the Abbasid Caliphate (founded in 750 CE) of Iraq in January 1258 CE. The Mongols captured Baghdad the following month after a brief siege. The week-long slaughter that followed - killing up to 800,000 people according to tradition - and the execution of the caliph, brought the collapse of the Abbasid Caliphate, although its empire was recentered in Cairo and became the Mamluk Sultanate (1261-1517 CE). The murder of the caliph was famously reported by Marco Polo and others; he met his end bricked up in a tower with all his treasure as a reminder he should have spent more money on defence. A less romantic (and more likely) version of events has the caliph wrapped up in a Persian carpet and kicked to death.

The Mongols swept on until they reached Syria and besieged Aleppo in December 1259 CE, the main city falling within a week and the usual slaughter of inhabitants following soon after. Then, in mid-1260 CE, news of Mongke's death reached them and the campaign was halted. A small Mongol army left in Syria was defeated by the Mamluks at the battle of Ain Julut on 3 September 1260 CE, but despite this most unusual of setbacks, the territory that Hulegu hard carved out, with its heartland in Iran, would become yet another slice of Asia under Mongol rule, the state known as the Ilkhanate.

Campaigns Against the Song

Kublai, meanwhile, had even higher ambitions, but for the moment he bided his time, taking the opportunity to create a local network of support and a team of talented advisors in northern China, notably Liu Bingzhong (1216-1274 CE). From 1253 CE, Mongke personally campaigned alongside Kublai in his attacks on southern China, still controlled by the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE). Mongol forces moved through Tibet and into Yunnan, subduing the Dali Kingdom in 1257 CE; Sichuan and eastern China were also overran. From the territory gained the Mongols could now strike at the weak underside of Song China, and so a four-pronged attack was planned to invade from the south and west. However, barely under weigh, the campaign came to a halt following Mongke's death on 11 August 1259 CE while he was besieging the Chinese city of Chongqing.

Death & Kublai Khan

Mongke's unexpected death not only brought an end to the Song campaign but also yet another scramble amongst the Mongol commanders over who might be his successor. The Mongol Empire was now essentially composed of four quite separate parts: the Golden Horde, the Ilkhanate, the Chagatai Khanate in central Asia, and the rump of Mongolia and northern China. Although Hulegu declined to forward himself as a candidate for the next khan, civil war ultimately broke out between the two main remaining candidates: Kublai and his younger brother Ariq Boke (1219-1266 CE), whom Mongke had nominated as his regent while he was on campaign against the Song. Both candidates declared themselves the new khan. Kublai had the support of Hulegu and the greater resources so that he won the four-year war and became the recognised new Great Khan in 1260 CE. Kublai would go on to expand the Mongol Empire to its greatest ever extent and, by at last conquering the Song, he would establish himself as the emperor of China under a new dynasty name: the Yuan Dynasty.