The Mystic Massacre of 1637 (also known as the Pequot Massacre) was the pivotal event of the Pequot War (1636-1638) in New England fought between the English (along with their Native American allies the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes) and the Pequot tribe of modern-day Connecticut.

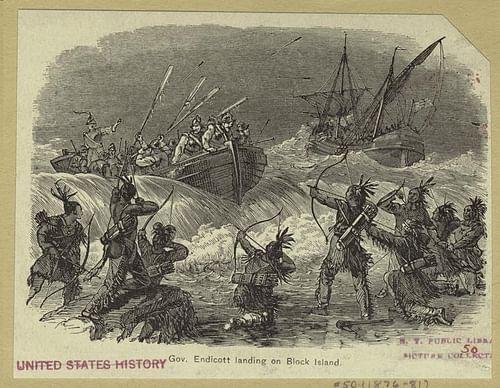

The conflict was initiated by the English who accused the Pequots and one of their tributaries, the Niantics, of murdering English traders. Even though governors Sir Henry Vane (l. 1613-1662), and John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649) both accepted the explanation of the Pequot chief Sassacus (l. c. 1560-1637) for the murders, as well as the wampum paid to atone for the deaths, Vane still sent John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665) to demand more of the Pequots in August of 1636.

Endicott’s demands included more wampum, Pequot children to be held as hostages to ensure good behavior, and the men responsible for the murders. When the natives refused, Endicott attacked them burning Niantic villages on Block Island, a Pequot village on the Connecticut River, and killing a number of people. The Pequots retaliated with raids on English settlements throughout the fall of 1636 and into the spring of 1637 until the Mohegans and Narragansetts led the English to the Pequot stronghold early in the morning of 26 May 1637 where they set the fort on fire and killed almost all of the Pequots found there. Estimates range from 500-700 killed either by burning to death, being shot as they ran from the flames, or by other means with most scholars agreeing on the higher number and, most likely, one even higher. Since the warriors were away from the fort with Sassacus at the time, most of the Pequots killed that morning were women and children.

Sassacus directed an attack on the colonists as they were returning home afterwards but did not have enough men to win an advantage. He retreated with his surviving members to New Netherlands (modern-day New York) to seek assistance from the Iroquois Confederacy but was executed by the Mohawks who sent his head and hands back to the English. Of the 3,000 Pequots living in Connecticut prior to the massacre, only approximately 200 survived. They were then sold into slavery or absorbed by other tribes and their lands divided among the victors by the Treaty of Hartford of September 1638.

The Mystic Massacre is considered a decisive event, not only in New England history but also in shaping the later colonial and then United States policy toward Native Americans. The colonial narratives of the massacre encouraged the view of natives as untrustworthy, bloodthirsty savages who needed to be reformed through conversion to Christianity and removed from contact with English, and then American, settlers. This policy would continue up through the 20th century and, subtly, still informs Anglo-Native relations today.

Initial Conflict & War

The Dutch had established trade with the Pequot by 1622 and built a trading post on the Connecticut River. Trade between the Dutch and Pequot had been ongoing since c. 1614, but after the English Plymouth Colony was founded in 1620, English colonists began competing with the Dutch for trade. Conflicts were resolved by a treaty between the English and the Dutch in 1627 dividing territories and tribes each would trade with.

In 1630, the Puritan English lawyer John Winthrop arrived with 700 colonists and established the Massachusetts Bay Colony around its capital at Boston. Governor Winthrop either did not know or chose to ignore the 1627 treaty and established a trading post upriver from the Dutch on the Connecticut River in 1633 to intercept fur shipments, leading to more conflicts between the English and Dutch and their respective Native American trade partners.

In 1634, the English Captain John Stone (d. 1634) was killed, allegedly, by Western Niantic warriors, tributaries of the Pequot, along with seven of his men in response to Stone’s actions against the natives, including kidnapping. John Winthrop sent his son to inquire into the situation, and the Pequots appeared before the magistrates at Massachusetts Bay. Scholar James A. Warren comments:

Massachusetts Bay agreed to establish trade relations with the Pequots…In return, the Pequots would surrender the killers of John Stone and pay the hefty sum of four hundred fathoms of wampum and seventy beaver and otter skins as tribute. The value of the tribute equaled 250 pounds sterling at the time, which was slightly less than half of the total property taxes levied by Massachusetts on its entire population in 1634…No matter its exact value, the tribute demanded was sufficiently draconian to amount to extortion. The Puritan authorities were probably well aware the “tribute” could not be paid in full under the best of circumstances. (81)

Sassacus rejected the demand as unreasonable, increasing tensions between the Pequot and the English. In 1636, Captain John Oldham (l. 1592-1636) was murdered and again the Niantics of Block Island were said to be the culprits. Vane sent Endicott to demand the surrender of the killers, children as hostages to guarantee future good behavior, and even larger payment in wampum and fur. The Pequot had already told Winthrop that they had mistaken Stone for a Dutchman and, regarding Oldham, had no knowledge of his death. When Endicott confronted the Niantics of Block Island, they repeated this but Endicott, famous for his quick temper and lack of patience, attacked them, killing one and burning their villages; he then did the same to a Pequot village on the river.

The Pequots responded by attacking the settlement of Fort Saybrook in Connecticut and others elsewhere throughout the fall of 1636 into the spring of 1637. They tried to get the Narragansetts to ally with them against the English, pointing out to them that, if the Pequots were defeated, the Narragansetts and other tribes would be next because the English clearly were not going to be content until they had all of the natives’ lands. The Narragansetts were considering the proposal but were convinced to side with the English by Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683), an exile from Massachusetts Bay who had lived among them and whom they trusted more than they did Sassacus.

Mason’s Account of the Massacre

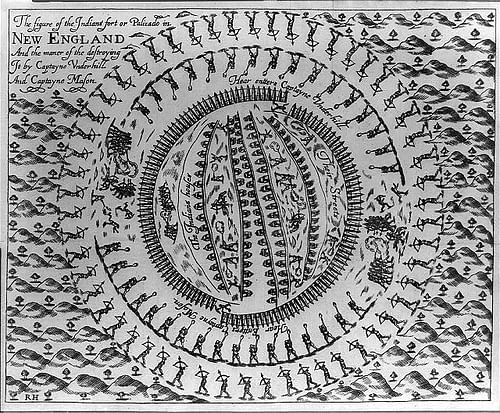

In May of 1637, it was decided the Pequots should be destroyed and militias were organized under captains John Underhill (l. 1597-1672) of Massachusetts Bay and John Mason (l. c. 1600-1672) of Connecticut Colony possibly with some volunteers supplied by Governor William Bradford (l. 1590-1657) of Plymouth Colony. They were led to the site of the Pequot fort by the Mohegans and Narragansetts, arriving early in the morning. Both Captain Underhill and Captain Mason – who would later become national heroes celebrated in story and statuary – wrote accounts of the action against the Pequots, which match well with each other. Part of Captain Mason’s account follows, beginning with their arrival at the Pequot fort, as given in Puritans in the New World: A Critical Anthology, edited by David D. Hall:

Captain Underhill came up and marched to the rear and, commending ourselves to God, divided our men. There being two entrances to the fort, intending to enter both at once, Captain Mason leading up to that on the northeast side, who approaching within one rod, heard a dog bark and an Indian crying “Owanux! Owanux!” which is “Englishmen! Englishmen!” We called up our forces with all expedition, gave fire upon them through the palisade; the Indians being in a dead indeed their last sleep. Then we wheeling off, fell upon the main entrance, which was blocked up with bushes about breast high, over which the captain passed, intending to make good the entrance, encouraging the rest to follow…We had formerly concluded to destroy them by the sword and save the plunder.

Whereupon Captain Mason, seeing no Indians, entered a wigwam; where he was beset with many Indians, waiting all opportunities to lay hands on him, but could not prevail. At length, William Heydon, espying the breach in the wigwam, supposing some English might be there, entered; but in his entrance fell over a dead Indian, but speedily recovering himself, the Indians some fled, others crept under their beds. The captain, going out of the wigwam, saw many Indians in the lane or street; he making towards them, they fled, and were pursued to the end of the lane, where they were met by Edward Pattison, Thomas Barber, with some others, where seven of them were slain, as they said.

The captain facing about, marched a slow pace up the lane he came down, perceiving himself very much out of breath, and coming to the other end near the place where he first entered, saw two soldiers standing close to the palisade with their swords pointed to the ground. The captain told them that we should never kill them after that manner. The captain also said, “We must burn them” and immediately stepping into the wigwam where he had been before, brought out a firebrand, and putting it into the mats with which they were covered, set the wigwam on fire. Lieutenant Thomas Bull and Nicholas Omstead beholding, came up and when it was thoroughly kindled, the Indians ran as men most dreadfully amazed.

And indeed, such a dreadful terror did the Almighty let fall upon their spirits, that they would fly from us and run into the very flames, where many of them perished. And when the fort was thoroughly fired, command was given that all should fall off and surround the fort, which was readily attended by all…

The fire was kindled on the northeast side to windward which did swiftly overrun the fort to the extreme amazement of the enemy, and great rejoicing of ourselves. Some of them climbing to the top of the palisade, others of them running into the very flames, many of them gathering to windward, lay pelting at us with their arrows and we repaid them with our small shot. Others of the stoutest issued forth, as we did guess, to the number of forty, who perished by the sword.

What I have formerly said is according to my own knowledge, there being sufficient living testimony to every particular. (248-249)

Commentary

The accounts of Underhill and Mason both make clear there were few warriors in the fort and the inhabitants, who should have been regarded as non-combatants as they were women and children, fled or tried to hide more often than they fought back. Even so, the massacre was hailed as a great victory and John Winthrop declared a day of thanksgiving to honor the safe return of the brave soldiers who had taken part in it. The English suffered casualties of two dead and 26 injured as contrasted with the 700 Pequots, who mounted a minimal defense. Even though the first-hand accounts make clear the details of the massacre, it was still hailed as a great victory of the forces of good over evil. Underhill’s account includes the passage:

When a people is grown to such a height of blood and sin against God and man, and all confederates in the action, there [God] hath no respect to persons, but harrows them, and saws them, and puts them to the sword, and the most terrible death that may be. Sometimes the Scripture declareth women and children must perish with the parents. Sometimes the case alters; but we will not dispute it now. We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings. (Warren, 91)

The association of the massacre with the Christian God and a day of thanksgiving informs modern-day Native American protests against the holiday of Thanksgiving Day in the United States, and with good reason. Drawing on the Old Testament narratives of the Hebrew heroes smiting the enemies of God, the English colonists characterized the Pequots as demonstrably evil and worthy of destruction even though the leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony had earlier accepted the explanation of the murders of Stone and Oldham and, most likely, understood that the Pequots could not easily pay the tribute demanded of them.

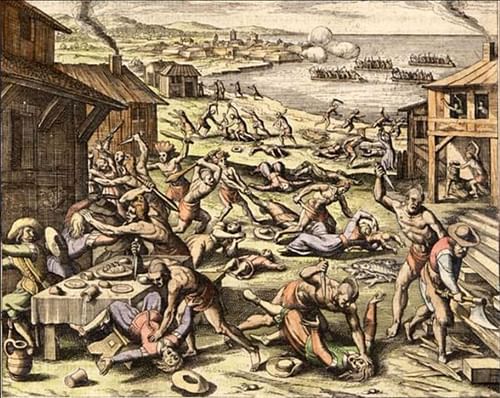

Influence of Indian Massacre of 1622

The Mystic Massacre of 1637, far from a triumph of good over evil, was nothing more than the English solution to dismantling the profitable Pequot-Dutch trade agreement and gaining access to Pequot lands. The only semblance of justification for the attack is the English colonists’ memory of the so-called Indian Massacre of 1622 at Jamestown Colony of Virginia, which haunted them. On 22 March 1622, Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646), chief of the Powhatan Confederacy of Virginia, attacked the settlements which had developed after the establishment of Jamestown, killing 347 colonists in a single morning. News of this attack reached New England within a month. The fear of another such action against New England colonists was a constant and, after the Pequot raids of the months leading up to the massacre, would have no doubt grown more intense.

This fear was not unfounded either. As noted, the Pequots had tried to convince the Narragansetts to ally with them to accomplish exactly what Opchanacanough had attempted in Jamestown in 1622: driving the English from the land. William Bradford, in his Of Plymouth Plantation, describes the Pequot proposal:

The Pequots…had sought to make peace with the Narragansetts and used very pernicious arguments to persuade them: the English were strangers, and were beginning to overspread their country, and would deprive them of it in time if they were allowed thus to increase. If the Narragansetts were to assist the English to subdue them, the Pequots, they would only make way for their own overthrow, for then the English would soon subjugate them; but if they would listen to their advice, they need not fear the strength of the English, for they would not make open war upon them, but fire their houses, kill their cattle, and lie in ambush for them as they went about the country – all of which they could do with but little danger to themselves. (Book II; ch. 18)

The colonists knew of this proposal through Roger Williams, who spoke Algonquian and served as an interpreter, but exactly when they knew is not clear. Even given the fear of an organized Native American assault on the settlements, however, the Mystic Massacre still cannot be justified as it was an assault on mainly defenseless women and children. Casting the massacre in the light of biblical narratives with the colonial militias as the instrument of God’s justice certainly made the colonists feel better about their crimes, but the Underhill and Mason accounts still show some evidence of lingering guilt which they had to suppress.

Conclusion

Sassacus and his followers retreated to the region of New Netherlands after the war, but news of the massacre had spread quickly, and other tribes were quick to seek the friendship of the English. The Mohawks executed Sassacus and sent his head and hands to the English, hoping to establish good relations. The Pequots who had accompanied him either remained with the Mohawks or returned to be enslaved, some sent to Bermuda or the West Indies and others given as slaves to local landowners or divided between the Mohegans and Narragansetts in accordance with the Treaty of Hartford of 21 September 1638, which also allocated the best lands along the Connecticut River – formerly Pequot territory – to the English. Most scholars in the present day fully recognize that the war was started on pretext to seize Pequot lands and the Mystic Massacre was completely unjustified and indefensible.

The Mystic Massacre would inform the actions of King Philip’s War (1675-1678) in New England just as the Indian Massacre of 1622 informed the Mystic Massacre. The tribes of the Wampanoag Confederacy under Metacom (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676) – as well as others, including the Narragansetts, who were non-combatants – were slaughtered by the English indiscriminately, enslaved, placed on reservations, and their lands seized for settlement after the Wampanoag were defeated.

King Philip’s War, in turn, set the policy of the colonists going forward in removing the indigenous tribes from their ancestral lands and pushing them further and further away from English settlements, creating the reservation system through which the former owners of the land could be contained and neutralized as a potential threat. Fortunately, many of the indigenous tribes survived the genocidal efforts of the English and, presently, are making significant strides in reclaiming their land rights, language, and cultural heritage.