Namazu (aka Onamazu) is the giant catfish of Japanese mythology held responsible for creating earthquakes. The creature was thought to live under the earth, and when it swam through the underwater seas and rivers there, it caused earthquakes. Subdued by the thunder god Takemikazuchi-no-mikoto, Namazu, nevertheless, remains a force to be reckoned with, even if he can, on occasion, bring good fortune and a redistribution of wealth as well as devastation.

The Japanese archipelago has suffered periodic and devastating earthquakes throughout its history (10% of the world's seismic activity occurs in Japan), and the creation of a monster which personified these terrible events was a mechanism which allowed people to explain and justify their seemingly random occurrence. The catfish Namazu swimming in the waters deep beneath the earth is thus an answer to the cause of the movement of the earth. Closely associated with the thunder gods, Namazu is seen as their counterpart below the earth. There was also another earthquake god, Nai-no-kami, who appears around the 7th century CE and later became identified with Namazu. In the Meiji Period (1868-1912 CE) Nai-no-kami was separated again and given his own personification.

Although Namazu was capable of great destruction, help was at hand from the heroic thunder and warrior god Takemikazuchi-no-mikoto (aka Kashima Daimyojin), for it was he who had a special stone, the kaname-ishi ('pinning rock'), and digging down into the earth he used the stone to weigh down Namazu's head, restricting his movements and so limiting the frequency, or at least the intensity, of earthquakes. The 15 cm tip of this massive stone which still projects through the earth's surface can be seen at the Kashima shrine of Hitachi, to the northeast of Tokyo. Thus, there is a popular saying: “Even if the earth moves, have no fear, for the Kashima kami (spirit) holds the the kaname-ishi in place” (Ashkenazi, 220).

One legend recounts that Tokugawa Mitsukuni (1628-1700 CE), perhaps in a fit of scepticism, attempted to excavate the kaname-ishi stone and see just how deep it went, but he gave up after seven days of digging and after he still hadn't found the bottom of the stone. Unfortunately, Namazu is not always pinned down for when Takemikazuchi-no-mikoto has to attend the annual conference of all the gods at Izumo, the catfish can squirm a little more than usual and cause an earthquake or two by thrashing his tail. Nevertheless, the idea spread of placing stones similar to the kaname-ishi at shrines to try and prevent or minimise earthquakes.

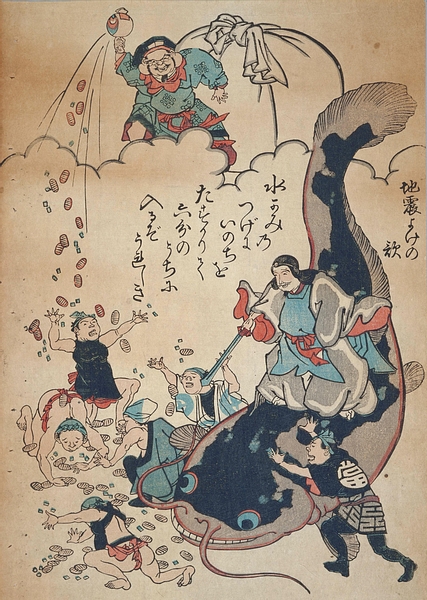

Namazu's efforts might bring destruction and despair but he does have a positive side. The catfish represented the regular renewal of the world known as yo-naoshi which was welcomed by the poor as an opportunity to shake up the wealthy classes, redistribute their accumulated riches, and make a new start. This idea became especially popular following a series of earthquakes in the Edo Period (1600-1868 CE) which many times reduced the haves to the level of the have-nots and provided the poor with a momentary opportunity to improve their lot in the chaos that immediately followed such disasters. The yo-naoshi idea includes the hope that the poor will inherit the wealth of the rich and this role-reversal has meant that Namazu is sometimes associated with good fortune, or more specifically a temporary fortune. This is manifested in shrines or depots sacred to a local deity with an aspect of Namazu. Known as kuramaya, people may borrow bowls and utensils from them, but Namazu will bring personal misfortune if they are not cared for and returned after use.

Takemikazuchi and Namazu were popular subjects in Japanese paintings, especially ukiyo-e prints, when they were used during the Edo Period as talismans in people's homes to prevent serious earthquakes from striking and invoke Takemikazuchi's help should they do so. Images of Namazu are still around today, too, and seen, for example, on the digital warning devices produced by Japan's Meteorological Agency.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.