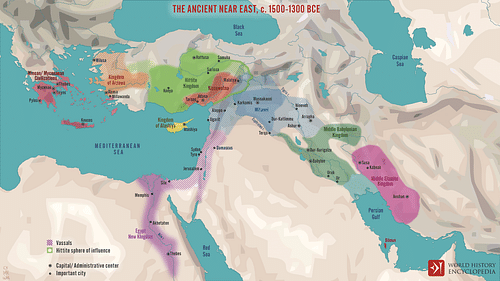

The Near East is a modern-age term for the region formerly known as the Middle East comprising Armenia, Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and part of Turkey, corresponding to ancient Urartu, Mesopotamia, Elam, Persia, the Levant, and Anatolia. The history of the ancient Near East is usually given as c. 5000 BCE-7th century CE.

Although human habitation of the region dates to the Stone Age (c. 10,000 BCE) and permanent settlements began to appear during the Neolithic Age around 7,000 BCE, the region’s history begins in the Chalcolithic Period (the Copper Age, c. 5,900-3,200 BCE) and, in Mesopotamia, in the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE) specifically. This corresponds roughly to developments in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) and other areas but there were sophisticated permanent settlements and sacred sites existing much earlier such as the city of Jericho (c. 9000 BCE) in Palestine and Gobekli-Tepe (c. 10000 BCE) in Anatolia (modern Turkey).

The Near East is often defined as the region bordered by the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea, Caspian Sea, Persian Gulf, and Red Sea, and access to these waterways encouraged long-distance trade, notably with the cities of the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 7000 - c. 600 BCE) as well as the various Near Eastern cities and ports. The region is often referred to as including the Fertile Crescent, and is known as the Cradle of Civilization, although civilization had also developed elsewhere, such as ancient China, the Indus Valley, and the Americas.

Even so, the Near Eastern region of Mesopotamia, specifically Sumer, is regarded as the oldest civilization on earth due to the established dating of inventions and developments which constitute civilization, including:

- Animal husbandry

- Agricultural innovations

- Urbanization

- Astronomy and mathematics

- The concept of time

- Long-distance trade

- Religious rituals and sacred sites

- Medical practices

- Scientific thought

- Technological innovations

The history of the ancient Near East ends with the conquest of the region by the Muslim Arabs in the 7th century CE and the fall of the Persian Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) which marks the beginning of the new phase of the region’s history.

Early Mesopotamian & Egyptian Periods

The term Near East, though widely used, is by no means universally accepted by modern-day scholarship as some writers still consider Middle East more accurate. Scholar Marc van die Mieroop comments:

The term “Near East” is not widely used today. It has survived in a scholarship rooted in the nineteenth century when it was used to identify the remains of the Ottoman empire on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Today we say Middle East to designate this geographical area, but the two terms do not exactly overlap, and ancient historians and archaeologists of the Middle East continue to speak of the Near East. (1)

The region’s long history and varied civilizations also present problems in creating a clear narrative of events which is all-inclusive and so most scholars focus on Mesopotamia with brief mention of the other regions and political entities that interacted with it. Following this lead, the history of the Near East begins with the Ubaid Period during which the first temples (the ziggurat) were built, and permanent settlements grew into small villages.

During the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) these villages developed into urban centers engaged in agriculture, manufacturing, and trade as the basis for their economy. Writing was invented in Sumer as cuneiform script (c. 3600 BCE) and the wheel followed soon after (c. 3500 BCE) along with other technological and agricultural innovations.

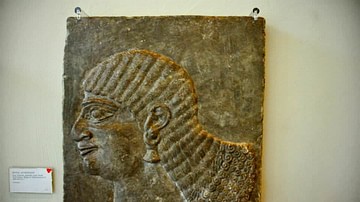

During this same era in Egypt, writing was developed as hieroglyphic script by the Naqada Culture III c. 3400-3200 BCE and some Egyptian cities, such as Xois, were already regarded as ancient by that time. The Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) established kingship when Narmer (also known as Menes) united the region and, by this time, trade with the cities of Mesopotamia had been ongoing for centuries.

Early Dynastic Period

During the Early Dynastic Period in Mesopotamia (2900-2334 BCE), kingship was established as society moved away from the concept of the ruler as priest-king (established during the Uruk Period) to a division of responsibility between a king and a high priest. The king would now concern himself with military matters and civic duties while the high priest would serve the god of the city and tend to matters concerning the temple complex.

By this time, the monumental structure of the ziggurat had already been appearing in Mesopotamian cities for centuries and scholars continue to debate whether these structures influenced the pyramids of Egypt that were raised during the period of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE). While this is a possibility, as the civilizations were in close contact through trade, it seems the pyramid developed from the earlier Egyptian mastaba tomb and had nothing to do with the ziggurat either in design or purpose. Egyptian pyramids were royal tombs; Mesopotamian ziggurats were religious sites topped by temples to a specific god. Egyptian pyramids were designed with interior rooms; Mesopotamian ziggurats were solid structures of mud brick with no interior chambers.

The Sumerian King List (composed c. 2100 BCE) gives the names and reigns of the Mesopotamian monarchs, claiming that kingship was established at the city of Eridu (founded in c. 5400 BCE) and passed to other cities from there. Just as there is no evidence of a connection between ziggurats and pyramids, there appears to be none between the concept of monarchy in Mesopotamia and that of Egypt. Mesopotamian administrative records and archaeological evidence also make clear that cities in the region differed from those elsewhere in that they were usually larger, walled, and were supported by often sprawling suburbs of farming communities.

First Empire & Sumerian Revival

Each Mesopotamian city-state was its own political and military entity until the rise of Sargon of Akkad (the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE) who unified the region under the Akkadian Empire. Sargon established the first multi-national political entity in the world and held it through careful placement of trusted officials in important positions in the various cities (such as his daughter, Enheduanna, l. 2285-2250 BCE, as high priestess of Ur) and by military strength. Sargon’s reign united the Near East region from modern-day Iraq through Jordan, Syria, the Levant, part of modern-day Turkey, to Cyprus.

The empire reached its height under the reign of Sargon’s grandson, Naram-Sin (2261-2224 BCE) but, after his death, declined and finally fell to the invading Gutians in c. 2218 BCE. The fall of Akkad initiated the Gutian Period in the region (2218-2047 BCE) which is characterized by scribes of the time (and afterwards) as a lawless time of chaos. This seems to have been something of an exaggeration as noted by scholar Paul Kriwaczek who cites climate change, bringing drought and famine, as the most likely cause for the fall of Akkad and the dark times that followed (129-130).

Whatever happened, trade in the Near East declined during the Gutian Period, as did construction of temples and other building projects, until the Sumerian King of Uruk, Utu-Hegal (r.c. 2055-2047 BCE) rose in revolt. After Utu-Hegal’s death, the war was continued by Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) who initiated the Ur III Period (also known as the Sumerian Renaissance), and hostilities were concluded with the victory of Ur-Nammu’s son, Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE). The Ur III Period was a time of great cultural revival and significant building projects such as the great Ziggurat of Ur.

By this time, many of the most important inventions and innovations of the Sumerians had been adopted by the other cultural entities of Mesopotamia and spread by trade throughout the Near East. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer, in his iconic work History Begins at Sumer, gives a list of 39 “firsts” appearing in ancient Sumer which influenced the development and culture of other Near Eastern civilizations:

- The First Schools

- The First Case of 'Apple Polishing'

- The First Case of Juvenile Delinquency

- The First 'War of Nerves'

- The First Bicameral Congress

- The First Historian

- The First Case of Tax Reduction

- The First 'Moses'

- The First Legal Precedent

- The First Pharmacopoeia

- The First 'Farmer's Almanac'

- The First Experiment in Shade-Tree Gardening

- Man's First Cosmogony and Cosmology

- The First Moral Ideals

- The First 'Job'

- The First Proverbs and Sayings

- The First Animal Fables

- The First Literary Debates

- The First Biblical Parallels

- The First 'Noah'

- The First Tale of Resurrection

- The First 'St. George'

- The First Case of Literary Borrowing

- Man's First Heroic Age

- The First Love Song

- The First Library Catalogue

- Man's First Golden Age

- The First 'Sick' Society

- The First Liturgic Laments

- The First Messiahs

- The First Long-Distance Champion

- The First Literary Imagery

- The First Sex Symbolism

- The First Mater Dolorosa

- The First Lullaby

- The First Literary Portrait

- The First Elegies

- Labor's First Victory

- The First Aquarium

In addition to these “firsts” of the Near East is Enheduanna, the first author in the world known by name, the dog collar and leash, the corbel arch and, from Egypt, the toothbrush and toothpaste, the true pyramid, and the first recorded female physicians – Merit-Ptah (l. c. 2700 BCE), physician of the royal court, and Pesehet (l. c. 2500 BCE), known as Lady Overseer of Female Physicians. Female dentists and doctors are referenced in ancient Mesopotamian texts but not by name.

Babylon & Hittites

The Sumerians fell to incursions of Elamites and Amorites and the latter established themselves, notably, at Babylon. Under Hammurabi, (r. 1792-1750 BCE), Babylon became the center of the great Babylonian Empire which controlled roughly the same region once held by Sargon of Akkad. After Hammurabi’s death, his empire fell apart and was taken by the Hittites and Kassites who established their own cultural and political centers.

The Hittite Period is divided by modern scholars into the era of the Old Kingdom (1700-1500 BCE) and the New Kingdom (also known as the Hittite Empire) of 1400-1200 BCE with an interregnum period between sometimes referred to as the Middle Kingdom. The Hittite Empire was at its height under King Suppiluliuma I (r. c. 1344-1322 BCE) and his son and successor Mursilli II (r. c. 1321-1295 BCE) but declined during the Bronze Age Collapse. Their decline was hastened by invasions by the Kaska tribe and the Sea Peoples who also contributed to the waning, sometimes temporarily and other times permanently, of other Near Eastern civilizations.

Assyrians, Persians, & Alexander the Great

The Assyrians under Adad Nirari I (r. c. 1307-1275 BCE) ended Hittite control in the region and established the city of Ashur in prominence, from which the Assyrian Empire steadily spread. The Assyrian Empire was the largest in the world up to that time, conquering territories from northern Syria through modern-day Turkey and across through Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine. The Neo-Assyrian Empire (912-612 BCE), the best-known and most well-documented period of their reign, continued the practice of forced deportation and relocation of the conquered, spreading the culture, religious ideas, and technologies of different people across the Near East.

The diverse population was controlled through the Assyrian’s military strength and strict laws, but the different regions were also held by the elevation of the god Ashur to the level of supreme deity. Ashur was originally only the god of the city of Ashur but, as the Assyrian army engaged in their campaigns of conquest, they carried their god with them and, with each victory, shrines were erected in his honor. From a local god presiding over a single city, Ashur became the supreme deity of all the Near East. Kriwaczek comments:

One might pray to Ashur not only in his own temple in his own city, but anywhere. As the Assyrian Empire expanded its borders, Ashur was encountered in even the most distant places. From faith in an omnipresent god to belief in a single god is not a long step. Since He was everywhere, people came to understand that, in some sense, local divinities were just different manifestations of the same Ashur. (231)

Monotheism had been attempted in Egypt under Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE) but had failed and all traces of his reign destroyed by his successors. It is unlikely that Akhenaten’s monotheism influenced any later development of it elsewhere (though this is possible) but the rise of Ashur is thought to have been more influential in suggesting a supernatural power who lived, not in a temple, as had been the belief throughout the Near East, but who was everywhere at once. As Kriwaczek notes, this belief encouraged significant changes in how people saw themselves in relation to the natural world:

Nature came to be desacralized, deconsecrated. Since the gods were outside and above nature, humanity – according to Mesopotamian belief created in the likeness of the gods and as servants to the gods – must be outside and above nature too. Rather than an integral part of the natural earth, the human race was now her superior and ruler. (229)

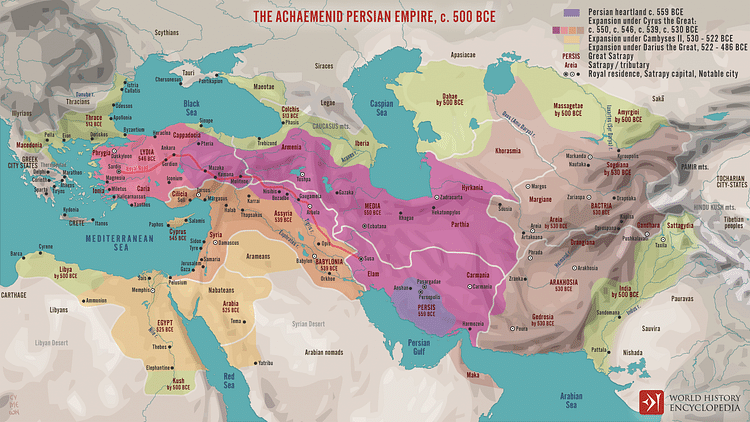

This belief also led to a decline in the status of women, a trend that had begun under the reign of Hammurabi when male deities began replacing earlier Sumerian and Akkadian goddesses. The all-powerful male deity encouraged a belief in the superiority of men and inferiority of women. After the Assyrian Empire fell to a coalition of their enemies in 612 BCE, this paradigm continued until c. 550 BCE when the region was taken by Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE), founder of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE). Under Cyrus II, and his successors, women’s status greatly improved (an aspect of their culture criticized by the Greek historian Herodotus) even though the Persian supreme deity, Ahura Mazda, was also envisioned as an omnipresent male.

Persian women ran their own businesses, served in the military, supervised males in the workplace, and were paid the same wages for the same jobs. Although Zoroastrianism had replaced the earlier Iranian polytheism, some of those deities, like the goddess Anahita, were still worshipped as aspects of Ahura Mazda and some scholars believe this practice provided a balance lacking in the earlier Assyrian religion.

The Persians introduced several cultural innovations familiar today such as the postal system, hospitals, refrigeration, air conditioning, birthday celebrations and dessert, animal rights, the precursor of the guitar (the sestar), and even the English word paradise from their word for an enclosed, landscaped garden.

The Persian Achaemenid Empire surpassed the Assyrian Empire as the largest and wealthiest in the world but was already in decline in 330 BCE when it fell to the armies of Alexander the Great. Alexander established his own empire in the region and, in doing so, spread Hellenistic thought and culture throughout the Near East, a process that would be continued by his successors.

Conclusion

After Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, his generals fought each other for control of the empire and Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE) took Mesopotamia and established the Hellenic Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE). The Seleucids combined Hellenic and Persian customs, expanding the empire toward the east until their power began to decline owing to a combination of factors including the rise of Rome, inefficient monarchs, and a territory too vast to maintain.

The Seleucids were replaced, even before their final fall, by the Parthian Empire (247 BCE-224 CE) who then gave way to the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE), both Persian political entities, who maintained the culture of the earlier Achaemenid Empire but had also been influenced by the Seleucids’ Hellenism. The Sassanian Empire maintained a high level of cultural development, including religious tolerance (except in some notable instances), women’s rights, and a focus on literacy in order to read the religious texts of the Avesta.

In 651 CE, the Sassanians fell to the Muslim Arabs who, in keeping with the practice of conquerors going back to the beginning of the region, suppressed the culture of the conquered and replaced it with their own. There were many aspects of Persian culture that were adopted, however, and as the Persians had preserved elements of earlier civilizations, aspects of these survived as well.

Still, the history of the ancient Near East was poorly understood until the 19th century when excavations in the region uncovered the ruins of the cities and the written works of the people. Up until the mid-19th century, Mesopotamian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics were considered some sort of ornamentation. Once they were understood to be written languages, the past opened up to the present, revealing some of the richest and most significant civilizations in the world.