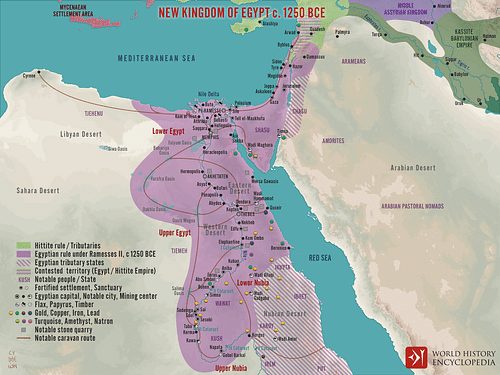

The New Kingdom (c. 1570- c.1069 BCE) is the era in Egyptian history following the disunity of the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-1570 BCE) and preceding the dissolution of the central government at the start of the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-c. 525 BCE). This is the time of Imperial Egypt when it became an empire.

It is the most popular era in Egyptian history in the present day with the best known pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty such as Hatshepsut, Thuthmoses III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, those of the 19th Dynasty like Seti I, Ramesses II (The Great), and Merenptah, and of the 20th Dynasty such as Ramesses III.

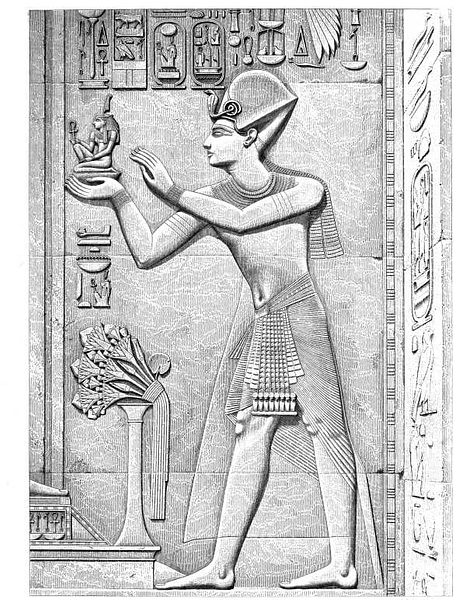

It is during the new kingdom that these Egyptian rulers are known as "pharaohs", meaning "Great House", the Greek word for the Egyptian Per-a-a, the designation of the royal residence. Prior to the New Kingdom Egyptian monarchs were known simply as "kings" and addressed as "your majesty". The fact that the word "pharaoh" is so commonly used to reference any Egyptian ruler from any era attests to the impact the New Kingdom has had on the modern-day understanding of Egyptian history.

The New Kingdom is the most completely documented period in Egyptian history. Literacy had expanded during the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) and Second Intermediate Period so that, by the time of the New Kingdom, more people were writing and sending letters. Further, Egypt was now in contact with other foreign powers through diplomatic relations and trade which necessitated written contracts, treaties, letters between kings, and bills of sale. The operation of the empire also required a large bureaucratic network which, of course, generated a vast amount of written material much of which is still extant.

During the Second Intermediate Period the foreign kings known as the Hyksos ruled in Lower Egypt from Avaris, the first time outsiders had managed to amass the kind of wealth and power to enable them to become a political force in Egypt. The Hyksos were driven out by Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE), founder of the 18th Dynasty and the New Kingdom period, who instantly set about securing and then expanding the borders of Egypt to provide a buffer zone against any further invasions.

Later pharaohs, most notably Thuthmoses III, expanded these buffer zones into an empire. This empire would elevate Egypt's status on the international stage, making her a member of the coalition modern historians call the "Club of Great Powers" along with Assyria, Babylon, the Hittite New Kingdom, and the Kingdom of the Mitanni all of whom participated in trade and diplomatic relationships.

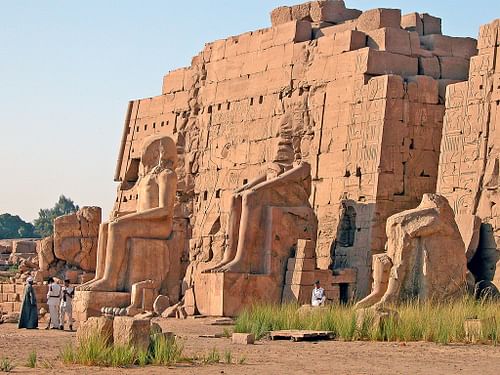

The 18th, 19th, and early 20th Dynasties brought Egypt to its height of power but during the latter part of the 20th Dynasty (known as the Ramessid Period) that power began to wane as the priests of Amun gained greater wealth and influence and the status of the pharaoh diminished. The power of the Cult of Amun can best be appreciated by the size of the temple to the god at Karnak which every ruler of the New Kingdom contributed to. By the end of the New Kingdom there were over 80,000 priests employed by the temple at Thebes alone, not counting other cities in various districts. The most notable of these priests were richer and owned more land than the pharaoh.

The unity and strength which characterized the 18th and 19th Dynasties steadily was lost during the 20th. The New Kingdom ended when the priests of Amun grew strong enough to assert their power at Thebes and divide the country between their rule and the pharaoh's at the city of Per-Ramesses. With the loss of a strong central government and monarch, Egypt entered the era known as the Third Intermediate Period which is characterized by a steady decline in power and concludes with the Persian invasion of Egypt in 525 BCE.

Beginning of the New Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom had been a time of unity and prosperity which dissolved during the 13th Dynasty so that by c. 1782 BCE a new power had been able to rise in the north of Egypt, that of the Hyksos. The Hyksos were Semitic peoples who established a seat of power at Avaris in Lower Egypt while, at the same time, the Kingdom of Kush rose in the south in Upper Egypt. These two powers were enabled to establish themselves so firmly because of the neglect of the latter part of the 13th Dynasty. The rule of the Hyksos and, to a lesser extent, the rise of Kush, characterize the era which 19th and 20th century CE scholars named the Second Intermediate Period.

Although Egyptian writers of the New Kingdom, and later, would characterize the time of the Hyksos as a time of chaos and destruction, the archaeological record - as well as evidence from the time - show this is a literary exaggeration intended to contrast the greatness of a strong, unified country (such as prevailed in the New Kingdom) with the disunity that came before it.

All evidence points to a cordial, if not warm, relationship between the foreign kings at Avaris and the Egyptian rulers at Thebes until the wars broke out which finally resulted in the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt. Further, the Hyksos introduced a number of cultural innovations, especially in warfare, which the Egyptians made use of in building their empire. Scholars Brier and Hobbs write:

However pleased the Egyptians may have been to evict the Hyksos, they owed a great debt to their former occupiers. Egypt learned about chariots and horses from the Hyksos along with the secret of producing bronze, a metal harder than their copper. Battles against the Hyksos also led Egypt to look beyond its northern borders for the first time and, with a better-equipped arm, eventually to dominate the Middle East. (27)

The war with the Hyksos began when the Egyptian king Seqenenra Taa (also known as Ta'O) interpreted a message from the Hyksos king Apepi as a challenge and went to war with him. Ta'O was killed, most likely in battle, and the cause was taken up by Kamose of Thebes (probably Ta'O's son) who claimed victory over the Hyksos after destroying the city of Avaris.

Later inscriptions from the time, and the archaeological record, show that Avaris was still a Hyksos stronghold in the time of the next king, Ahmose I, who fought three battles to take it and drove the Hyksos first to Palestine and then to Syria. With the defeat of the foreign kings and their expulsion from Egypt, Ahmose I re-established his borders, pushed the Kushites further to the south, unified the country under his rule from the city of Thebes, and thus initiated the period of the New Kingdom.

The 18th Dynasty

Ahmose I understood that the Hyksos had been able to establish themselves so firmly because they had been allowed to by earlier Egyptian monarchs. He therefore decided to create buffer zones around Egypt to secure the borders and fortified neglected settlements at key spots to guard the country. Ahmose I's struggle against the Hyksos brought him and his army into contact with the regions of Palestine and Syria where he continued his campaigns as well as leading military expeditions south against the Kingdom of Kush in Nubia. When he died he had consolidated his rule and secured the country leaving a stable political and economic situation for his successor Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE).

Amenhotep I maintained his father's policies and emulated him as a warrior king in inscriptions but probably only led campaigns in Nubia. There are no records of him leading expeditions into Palestine or Syria but he may have since those regions remained secure during his reign and that of his successor. Amenhotep I is best known for his contributions to the arts and religious developments. The Book of Coming Forth by Day (better known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead) attained its final form under his reign and he was the patron of the artist's colony of Deir el-Medina, the village responsible for work done on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings where the great pharaohs were buried.

He concentrated his efforts on creating temples, stelae, and securing the borders but made no serious attempts at expanding Egypt's territory. Upon his death he was deified as the god of the artisans of Deir el-Medina and was venerated by a funerary cult in his name. He was succeeded by Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) who instantly began campaigns to broaden Egypt's reach.

Thutmose I put down a rebellion in Nubia which broke out shortly after he came to the throne, personally killing the Nubian king and hanging his body from his ship's prow as a warning to other rebels. He then expanded Egypt's hold on Nubia further south before turning his attention to Palestine and Syria. He added to the great Temple of Karnak at Thebes and erected numerous other temples and monuments throughout Egypt. He was succeeded by Thutmose II (1492-1479 BCE) about whose reign little is known because he was instantly overshadowed by his more powerful half-sister Hatshepsut.

Thutmose II was the son of Thutmose I by a lesser queen while Hatshepsut was Thutmose I's legitimate daughter and, according to her inscriptions, his designated heir. Thutmose II married Hatshepsut to secure his succession after Thutmose I's death but no records survive which suggest he ever had any real power. He may have ordered military expeditions into Syria but led none himself and it is actually thought that these campaigns were commissioned by his half-sister/wife.

Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) is among the most powerful and successful of the New Kingdom monarchs. She had one child with Thutmose II and he had another by a minor wife whom he designated as successor, Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE). Hatshepsut was named regent of Egypt upon Thutmose II's death and ostensibly co-ruled with the child Thutmose III but she had been the power behind her husband's reign and continued to do as she thought best after his death.

Hatshepsut is responsible for more building projects than any other Egyptian ruler except for Ramesses the Great (1279-1213 BCE). She organized and commissioned the most successful expedition to the Land of Punt, contributed her own works to the temple at Karnak, and ruled in peace with Nubia to the south. Her building projects were so beautiful, and so numerous, that later pharaohs claimed them as their own. They were able to do this because, sometime around 1458 BCE, Hatshepsut's name was removed from all her monuments, including her magnificent complex at Deir el-Bahri.

It is unclear why her name was removed, or by whom, but it seems it was the work of her successor Thutmose III who tried to blot out the reign of a female pharaoh in order to maintain the traditional gender roles in the culture. He may have felt that a strong and successful female ruler would empower other women to seek power and so upset the natural balance.

Thutmose III was handed a prosperous and stable nation in 1458 BCE and took no time to begin improving upon it. It is Thutmose III who creates the Egyptian Empire which would be maintained by his successors. He used the war chariot inherited from the Hyksos, as well as bronze weapons and superior tactics, to defeat the surrounding nations and expand Egypt's domain further than it had ever reached in the past.

In 20 years he led at least 17 different military campaigns , subduing kingdoms from Libya to Syria into Egyptian subjects and extending Egypt's control in the south from the area around Buhen down to Kurgus. His inscriptions and monuments tell his story so completely he is regarded as one of the best-documented rulers in Egyptian history after Ramesses II.

He was succeeded by his son Amenhotep II (1425-1400 BCE) who, like his father, inherited a strong and secure kingdom and improved on it. He was not as active in military campaigns as his father but commissioned numerous building projects and concluded peace treaties and trade documents with other nations such as the Mitanni. His successor, Thutmose IV (1400-1390 BCE), continued his policies. Thutmose IV is considered a usurper, even though he is the legitimate son of Amenhotep II, based upon interpretations of his famous Dream Stele which tells the story of how he came to the throne. He is best known as the pharaoh who restored the Great Sphinx at Giza.

He is succeeded by Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE) who is also considered one of the most successful and powerful rulers of Egypt. Amenhotep III reigned over Egypt at one of its highest points culturally, politically, and economically. His reign is among the most opulent in the history of Egypt and he consistently used his wealth in dealings with other countries to coax them into doing what he wanted. He maintained a stable rule of the country, expanded its borders, and devoted himself to the arts and building projects. Many of the most impressive Egyptian monuments come from his reign.

During his time, however, the priests of Amun began to acquire more and more wealth. They owned more land than the king and made use of it to further enrich themselves. Amenhotep III tried to quell their growing power by aligning himself with a minor god, Aten, represented by a sun disc.

It seems he thought the power of pharaoh behind the cult of Aten would increase the prestige of those priests at the expense of those of Amun. His plan did not work but it did elevate the god Aten who would feature prominently in the reign of Amenhotep's son and successor.

Amenhotep IV is better known as Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) the pharaoh famous for instituting monotheism in Egypt and banishing the old gods. The time of his reign has come to be known as the Amarna Period because the Egyptian capital was moved from Thebes to modern-day Amarna. He came to the throne as Amenhotep IV but, in the fourth or fifth year of his reign, changed his name to Akhenaten, abolished the old religion - especially the cult of Amun - and elevated the god Aten to the position of the one true god.

Only the Cult of Aten was viewed as a legitimate religious body; all the temples to the other gods were closed and their worship proscribed. At the great Temple of Amun at Karnak, which he also closed, he erected a temple to Aten. Akhenaten moved the capital from Thebes to a new city he had built, Akhetaten, to which he retired and largely neglected affairs of state. His wife was the famous Nefertiti (c. 1370-1336 BCE) best known for the magnificent bust created by the sculptor Thutmose.

Akhenaten's reforms have long been regarded as a sincere effort at religious reformation but may have simply been his most effective solution to the problem of the growing power of the Cult of Amun. As noted, the priests of Amun were a cause of concern to Akhenaten's father whose efforts at curbing the cult failed. Akhenaten effectively neutralized the power of the priests by outlawing their cult and banishing their god.

Upon Akhenaten's death he was succeeded by his young son Tutankhaten who swiftly changed his name to Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE), moved the capital back to Memphis, restored the religious center of Thebes (which also held political significance), re-opened the temples, and brought back the old religion to Egypt. Although he initiated important reforms which stabilized the country, he is best known for his magnificent tomb discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter. Tutankhamun was married to his half-sister, Ankhsenamun, until his death at the age of approximately 18.

Ankhsenamun may have then married the vizier Ay (possibly 1324-1320 BCE) who, according to some scholars, succeeded Tutankhamun or she may have tried to rule on her own. A letter from her to the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (1344-1322 BCE) asks for one of his sons in marriage whom she would make an Egyptian king. This son was sent by the king but was murdered upon reaching Egypt and it has been suggested this was carried out either by Ay or Horemheb. Whatever role Ay played in the succession, Ankhsenamun vanishes shortly after Tutankhamun's death and the general Horemheb came to power, devoting himself to restoring Egypt to her former glory.

Horemheb (1320-1295 BCE) went to great lengths to wipe the Amarna Period kings from Egyptian history by destroying all the monuments and inscriptions of Akhenaten, including demolishing his temple at Karnak so thoroughly that no trace was left of it. The only way later historians learned of Akhenaten's reforms was because Horemheb used the ruined monuments, stelae, and inscriptions as fill in other projects.

Horemheb championed the old religion and the traditions of ancient Egypt. Under Akhenaten's reign relationships with other nations, and the infrastructure of Egypt itself had been neglected. Horemheb restored Egypt to its former stature even though he could not raise it to the height it had known under Amenhotep III. He died without an heir and was succeeded by his vizier Paramesse who took the throne name Ramesses I (1292-1290 BCE) who began the 19th Dynasty.

The 19th Dynasty

Ramesses I was an elderly man when he came to the throne and fairly quickly appointed his son, Seti I, as successor. Ramesses I continued the work begun by Horemheb in rebuilding Egypt's temples and shrines and adding to the great Temple of Amun at Karnak. He authorized Seti I to carry out military expeditions to win back territories lost during the reign of Akhenaten.

When he died, Seti I (1290-1279 BCE) took the throne and continued the reformation and revitalization of Egypt, adding his own touches to the grand project at Karnak and grooming his successor for rule. His son, Ramesses II (known as The Great, 1279-1213 BCE) is the best known pharaoh of Egypt in the modern day because of his long association with the unnamed Egyptian ruler in the biblical Book of Exodus and his depiction in film adaptations of that story.

The actual Ramesses II was not the pharaoh of the Exodus story and there are a number of very strong arguments clarifying this. Among them is the fact that, more than any other pharaoh in history, Ramesses II documented his reign thoroughly. This king left more monuments and inscriptions behind than any other and yet nowhere in any of these is there any mention of Hebrew slaves, plagues, or the mass migration of upwards of 600,000 people from Egypt.

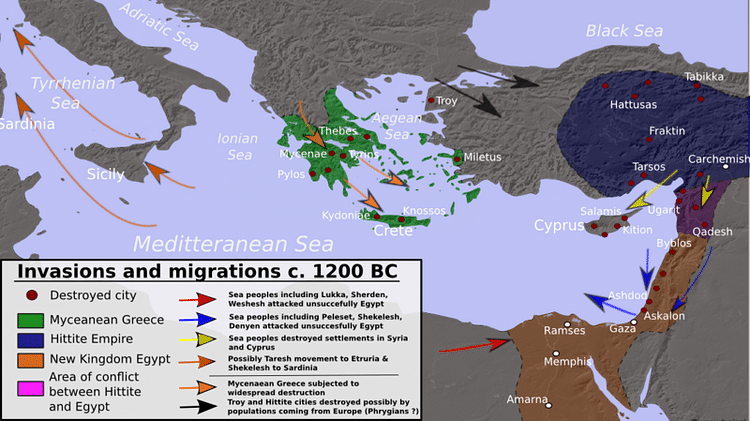

Ramesses II famously defeated the the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE, a feat he was most proud of (although the battle was more of a draw), and signed the world's first peace treaty. He also stopped an invasion by the Sea Peoples and secured the country against further attacks. He is routinely depicted as a great hunter and warrior-king, an image he encouraged, even though he led few, if any, campaigns after Kadesh.

Egypt flourished under the reign of Ramesses II. He erected so many monuments and left so many inscriptions that there is no ancient site in the country which does not bear some mention of his name. In an effort, perhaps, to secure the northern regions of the country he moved the capital from Thebes to a new city he built at Avaris called Per-Ramesses (also known as Per-Ramesu) which he divided into quarters each dedicated to a god, two Egyptian deities and two Asiatic, suggesting he was trying to blend Egyptian culture with that of Syria-Palestine. Whatever his motivation in moving the capital, it would later prove a mistake in that it allowed the priests of the Cult of Amun at Thebes to consolidate power to the point where they would rival the pharaohs.

Ramesses II lived to be 96 years old and, when he died, his people could not remember a time when he had not been king. His death caused wide-spread panic among the populace who were facing a future without Ramesses II as king. He was succeeded by his son Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE) who was almost 60 years old when he came to power.

Merenptah was the thirteenth son of Ramesses II and was not his chosen successor. He only became pharaoh because all of his brothers had died in the course of their father's long life and reign. Merenptah quickly aligned himself with his father's image as warrior king defeating the Libyans in battle and driving back an invasion of the Sea Peoples. His account of his campaigns includes the famous Merenptah Stele which provides the first mention of the people of Israel as a tribe.

He was succeded by Amenmesse (1203-1200 BCE) who was a usurper attempting to take power from the rightful heir Seti II (1203-1197 BCE). Amenmesse was most likely a son of Merenptah but not the chosen successor. Evidence suggests that Amenmesse tried to erase any evidence of Seti II, seized power at Thebes and extended it south through Nubia, and forced his kingship on the court. His date of death is unknown but he vanishes from the record after 1200 BCE while Seti II's reign extend to 1197 BCE.

He followed the precepts of Merenptah and initiated his own building projects including improvements/additions to the Temple of Karnak. He was succeeded by Merenptah Siptah (1197-1191 BCE) who came to the throne as a ten year old and died around the age of sixteen. His stepmother Twosret (also known as Tausret, 1191-1190 BCE) reigned with him as regent and succeeded him at his death. Twosret ruled two more years before she died and was succeeded by Setnakhte (1190-1186 BCE) a usurper who founded the 20th Dynasty of Egypt.

The 20th Dynasty

The evident confusion of rule following the death of Merenptah suggests that the succession of Egyptian kings was broken allowing usurpers to ignore the earlier traditions. This would have been a serious breach of the concept of ma'at (harmony, balance) if it had been tolerated or condoned. Amenmesse was defeated in his attempts but Setnakhte was accepted; suggesting that Setnakhte was not so obviously a usurper and was most likely one of the sons of Seti II.

Setnakhte stabilized the government but records from his reign appear confused. He may have driven off another invasion of the Sea Peoples or could have simply been repeating a story concerning Egypt's past. He was succeeded by Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) best known for defeating the Sea Peoples and driving them from the coasts of Egypt for the last time. Ramesses III's inscriptions regarding his battle with the Sea Peoples encourages the claim by some scholars that Setnakhte had fought them previously but this claim is not widely supported.

Ramesses III is the last strong pharaoh of the New Kingdom. The power of the priests of Amun had continued to grow once Horemheb revived the old religion and their steady ascent drew revenue and influence away from the throne. As in the time of Akhenaten, the priests of Amun held more land than the pharaoh and commanded greater authority in the provinces. This situation would worsen throughout the Ramessid Period of the 20th Dynasty.

Ramesses III maintained a strong central government, secured the borders, and kept Egypt prosperous but the empire was slipping away from him. The office of the pharaoh of Egypt no longer commanded the kind of respect it had previously because the priests of Amun fulfilled the role of an intermediary with the gods. Ramesses III was wounded in an assassination attempt orchestrated by one of his lesser wives and later died of his injuries. His successor, Ramesses IV (1155-1149 BCE), only came to the throne because his older brothers had died. He tried his best to emulate the great pharaohs of the past, and did accomplish a number of building projects while struggling to maintain the shrinking empire, but died after a short reign.

He was then succeeded by his son Ramesses V (1149-1145 BCE) who struggled to maintain power against the priests of Amun and hold together the empire. His successor, Ramesses VI (1145-1137 BCE), continued this struggle with no better success. Instead of great accomplishments in battle or monumental projects, Ramesses VI is best known among modern day historians for his tomb - but not for any great riches found inside. When Ramesses VI's tomb was built the workmen inadvertently buried the earlier tomb of Tutankhamun, keeping it safe from grave robbers until the 20th century CE.

He was succeeded by Ramesses VII (1137-1130 BCE), then Ramesses VIII (1130-1129 BCE) about whom nothing is known, then Ramesses IX (1129-1111 BCE), Ramesses X (1111-1107 BCE) and Ramesses XI (1107-1077 BCE). All of these pharaohs struggled to maintain the empire in the face of incursions from outside forces and internal struggles with the priests of Amun. An episode relating to these struggles, though far from clear, has to do with a man named Amenhotep, High Priest of Amun, who was ousted from his office by the vizier Pinehasy who then had to flee south to Nubia.

Amenhotep seems to have been reinstated by Ramesses XI during the period known as Whm Mswt (Wehum Mesut) which literally has to do with a rebirth of culture but seems the time when the power of the Egyptian monarchy declined rapidly. Although some ancient fragments of records seem to indicate Amenhotep the High Priest was restored to his position at Thebes, others claim he was succeeded by another priest named Herihor who was powerful enough to rule Egypt from Thebes, dividing the country with Ramesses XI. Unlike the rest of the New Kingdom, the records from this time are less complete and many are fragmentary. The only aspect of the time which does seem clear, though, is that the priests of Amun now had enough power to reign as pharaohs from Thebes.

Fall of the New Kingdom

This division of rule between Thebes in Upper Egypt and Ramesses XI's reign in Lower Egypt resulted in the same kind of disunity which characterized the First and Second Intermediate Periods. Again there was no strong central government in Egypt and the policies of the past which had preserved the empire were no longer effective. Historian Margaret Bunson writes how the Ramessid pharaohs had "little military or administrative competence" after Ramesses III and that "the 20th Dynasty, and the New Kingdom, was destroyed when the powerful priests of Amun divided the nation and usurped the throne" (81).

Ramesses II's decision to move the capital north to Avaris weakened the government by abandoning Thebes to the priests. Although ostensibly the Cult of Amun was under the authority of the pharaoh, in reality power rested in the hands of the party with the greatest wealth and influence. The priests of Amun were able to acquire massive amounts of land and profit from it without any interference from the pharaohs who were now so far away in the north.

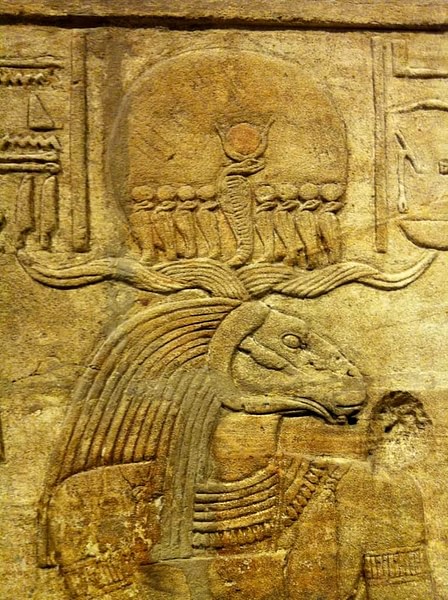

These priests were able to amass wealth to begin with because of the way the god Amun had come to be seen. He combined the aspects of the earlier creator god Atum with the sun god Ra and became recognized as the King of the Gods. The early pharaohs of the New Kingdom, like the kings before them, associated themselves with the god Horus but Seti I aligned himself with Horus' adversary Set and the Ramessid pharaohs with the sun god Ra. The name "Ramesses" comes from the Egyptian `Ra-Moses' meaning "Son of Ra".

The priests of Amun, the supreme deity, were in direct contact with the creator and sustainer of the universe, a god greater than Ra or Horus or Set. As worship of Amun increased in popularity so did his cult and so did their wealth. More importantly, however, the power of the pharaoh diminished as he was no longer seen as a necessary intermediary between the people and their gods. Now the priests of Amun could intercede on the people's behalf and they could receive answers directly. Scholar Jacobus Van Dijk comments on this:

The king no longer represented god on earth but was subordinate to him; just like all other human beings, he was subject to the will of god...Once it had been recognized that god's will was the governing factor in everything that happened, it became mandatory to know his will in advance. Oracles, which had originally been consulted only by the king, perhaps as early as the Old Kingdom began to be used in the Ramessid Period to consult the god on all sorts of affairs in the lives of ordinary human beings. Priests would carry the portable bark with the god's image in procession out of the temple and a piece of papyrus or an ostracon bearing a written question would be laid before him; the god would then indicate his approval or disapproval by making the priests move slightly forwards or backwards or by some other motion of the bark. Appointments, disputes over property, accusations of crimes, and later even questions seeking the god's reassurance that one would safely live in the hereafter, were thus subjected to the god's will. All of these developments further minimalized the role of the king as god's representative on earth; the king was no longer a god, but god himself had become king. Once Amun had been recognized as the true king, the political power of the earthly rulers could be reduced to a minimum and transferred to Amun's priesthood. (Shaw, 306-307)

The 20th Dynasty ends with the death of Ramesses XI and his burial by his successor Smendes I (1077-1051 BCE). A tradition going back to the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150-2613 BCE) was that whoever buried the king succeeded him. Smendes I was from Tanis in Lower Egypt and so, after burying the dead pharaoh, proclaimed himself successor and centered his capital there. He only ruled in Lower Egypt and eventually over a fairly limited territory. The New Kingdom concludes c. 1069 BCE under his reign as he becomes more of a provincial monarch. The priests of Amun held power at Thebes in Upper Egypt and the Nubians in the south, with no central Egyptian power to hold them in check, took back the lands they had lost under Thuthmose III and the other great pharaohs of the New Kingdom.

The regions of Syria, Palestine, and Libya followed suit and the Egyptian Empire fell. The country then entered another era of division and weakness known as the Third Intermediate Period but, unlike the previous times of transformation between unified eras, Egypt would not emerge from this one stronger and more advanced than before. The First and Second Intermediate Periods led to the Middle and the New Kingdoms but the Third Intermediate Period concludes with the Persian invasion of Egypt following the Battle of Pelusium in 525 BCE.

After the Persians arrived Egypt never again became an autonomous state for any great length of time. The 30th Dynasty (c.380-343 BCE) succeeded in re-establishing Egyptian rule but the country was again taken by the Persians who would rule until their defeat by Alexander the Great. The closest the country would come to Egyptian rule again would be under the dynasty of the Ptolemies (323-30 BCE), the Greek rulers who revived Egyptian customs and traditions. Theirs would be the last dynasty of Egypt before the coming of Rome.