Ninhursag (also Ninhursaga) is the Sumerian Mother Goddess and one of the oldest and most important in the Mesopotamian Pantheon. She is known as the Mother of the Gods and Mother of Men for her part in creating both divine and mortal entities.

She replaced the earlier Mother Goddess, Nammu (also known as Namma) whose worship is attested as early as Dynastic III (2600-2334 BCE) of the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE). Ninhursag had many different names given in various myths according to her particular role or the theme of the story.

She was originally known as Damkina and Damgalnuna in Sumer, a nurturing mother goddess associated with fertility in the city of Malgum. Her husband/consort was Sul-pa-e, a minor god associated with the underworld, with whom she had three children (Asgi, Lisin, and Lil). She is far more frequently depicted as the wife/consort of Enki, god of wisdom among many other attributes.

'Ninhursag' means 'Lady of the Mountain' and comes from the poem Lugale in which Ninurta, god of war and hunting, defeats the demon Asag and his stone army and builds a mountain of their corpses. Ninurta gives the glory of his victory to his mother Ninmah ('Magnificent Queen') and renames her Ninhursag.

She is also known as Nintud/Nintur ('Queen of the Birthing Hut') and, to the Akkadians, as Belet-ili ('Queen of the Gods'). Her other names include Makh, Ninmakh, Mamma, Mama, and Aruru. In iconography she is represented by a sign resembling the Greek symbol Omega often accompanied by a knife; this is thought to represent the uterus and the blade used to cut the umbilical cord thus symbolizing Ninhursag's role as mother goddess.

She first appears in written works during the Early Dynastic I Period (c. 2900-2800 BCE), but physical evidence suggests worship of the Mother Goddess figure dating back to at least 4500 BCE, during the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE), before the Sumerians had come to the region of southern Mesopotamia. Ninhursag is among the most likely candidates for the original "mother earth" figure, developing from Nammu, as she is associated with fertility, growth, transformation, creation, pregnancy, childbirth, and nurture.

Another of her early names, Ki or Kishar, identifies her as 'mother earth.' She was often invoked by mothers as she was thought to form and care for the child in the womb and provide food after he or she was born. Ninhursag is one of the four creating deities in Sumerian religious belief (along with Anu, Enlil, and Enki) and is frequently mentioned in many of the most important Mesopotamian myths.

Enki & Ninhursag

The Sumerian myth Enki and Ninhursag tells the story of the beginning of the world in the garden of paradise known as Dilmun. Ninhursag, depicted as a young and vibrant goddess, has retired for the winter to rest after her part in creation. Enki, god of wisdom, magic, and fresh water, finds her there and falls deeply in love with her. They spend many nights together, and Ninhursag becomes pregnant with a daughter they name Ninsar ('Lady of Vegetation'). Ninhursag blesses the child with abundant growth, and she matures into a woman in nine days. When spring comes, Ninhursag must return to her duties of nurturing living things on earth and leaves Dilmun, but Enki and Ninsar remain.

Enki misses Ninhursag terribly and, one day, sees Ninsar walking by the marshes and believes her to be the incarnation of Ninhursag. He seduces her, and she becomes pregnant with a daughter Ninkurra (goddess of mountain pastures). Ninkurra also develops into a young woman in nine days, and Enki again believes he sees his beloved Ninhursag in the girl.

He leaves Ninsar for Ninkurra whom he seduces, and she gives birth to a daughter named Uttu ('The Weaver of Patterns and Life Desires'). Uttu and Enki are happy together for a while, but just as with Ninsar and Ninkurra, Enki falls out of love with her once he realizes she is not Ninhursag and leaves her, returning to his work on earth.

Uttu is distraught and calls upon Ninhursag for help, explaining what has happened. Ninhursag tells Uttu to wipe Enki's seed from her body and bury it in the earth of Dilmun. Uttu does as she is told, and nine days later, eight new plants grow from the earth. At this point, Enki returns along with his vizier Isimud.

Passing by the plants, Enki stops to ask what they are, and Isimud plucks from the first and hands it to Enki, who eats it. This, he learns, is a tree plant and finds it so delicious that Isimud plucks the other seven, which Enki also quickly eats. Ninhursag returns and is enraged that Enki has eaten all of the plants. She turns on him the eye of death, curses him, and departs from paradise and the world.

Enki becomes sick and is dying, and all the other gods mourn, but no one can heal him except for Ninhursag, and she cannot be found. A fox appears, one of Ninhursag's animals, who knows where she is and goes to bring her back. Ninhursag rushes to Enki's side, draws him to her, and places his head against her vulva. She kisses him and asks him where his pain is, and each time he tells her, she draws the pain into her body and gives birth to another deity. In this way, eight of the deities most favorable to humanity are born:

- Abu - god of plants and growth

- Nintulla - Lord of Magan, governing copper & precious metal

- Ninsitu - goddess of healing and consort of Ninazu

- Ninkasi - goddess of beer

- Nanshe - goddess of social justice and divination

- Azimua - goddess of healing and wife of Ningishida of the underworld

- Emshag - Lord of Dilmun and fertility

- Ninti - 'the Lady of the rib,' who gives life

Enki is healed and repents for his carelessness in eating the plants and thoughtlessness in seducing the girls. Ninhursag forgives him, and the two return to the work of creation.

The myth represents Ninhursag as all-powerful in that she is able to inflict death on one of the most potent gods and is also the only one who can heal him. Enki and Ninhursag has also been cited, however, as the basis for the biblical story of creation found in Genesis. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer writes:

Perhaps the most interesting result of our comparative analysis of the Sumerian poem is the explanation which it provides for one of the most puzzling motifs in the biblical paradise story, the famous passage describing the fashioning of Eve, "the mother of all living", from the rib of Adam - for why a rib? Why did the Hebrew storyteller find it more fitting to choose a rib rather than any other organ of the body for the fashioning of the woman whose name, Eve, according to the biblical notion, means approximately "she who makes live". The reason becomes quite clear if we assume a Sumerian literary background, such as that represented by our Dilmun poem, to underly the biblical paradise tale; for in our Sumerian poem, one of Enki's sick organs is the rib. Now the Sumerian word for "rib" is ti (pronounced tee); the goddess created for the healing of Enki's rib was therefore called in Sumerian Nin-ti "the Lady of the rib". But the Sumerian word ti also means "to make live" as well as "the Lady of the rib". In Sumerian literature, therefore, "the Lady of the rib" came to be identified with "the Lady who makes live" through what may be termed a play on words. It was this, one of the most ancient of literary puns, which was carried over and perpetuated in the biblical paradise story, although there, of course, the pun loses its validity, since the Hebrew words for "rib" and "who makes live" have nothing in common. (149)

Aside from the influence on the later biblical tale, the myth makes clear the power of the mother goddess figure in Sumerian belief. None of the male gods who have participated in creation - not even the most powerful such as Anu or Enlil - can do anything to heal Enki; only the mother goddess can draw out the sickness and turn death into life. In all the myths concerning her, Ninhursag is associated with life and power, but Enki comes to rival and, finally, dominate her.

Enki & Ninmah

In the myth of Enki and Ninmah, Ninhursag begins on equal footing with the god, but by the end, loses her status. It is known that the female deities in Mesopotamia were overshadowed by the males during the reign of Hammurabi of Babylon (1792-1750 BCE). If it could be authoritatively determined that the story of Enki and Ninmah dated from this time, then the myth would correspond to the overall decline in stature and equality goddesses (and women) were then experiencing. No firm date has been established for the work, however. As scholar Jeremy Black notes:

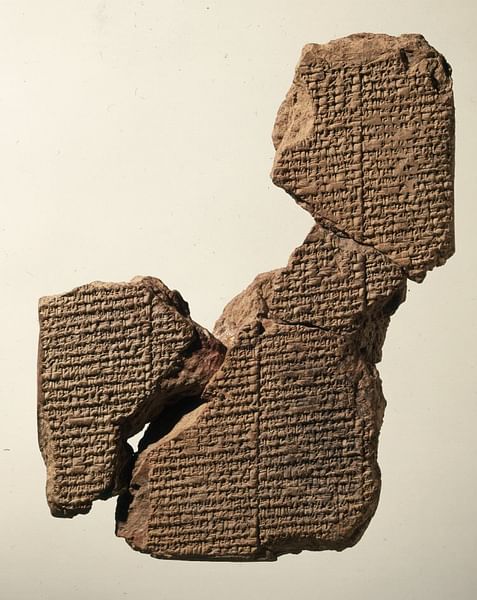

Lack of anything but a fairly general historical framework for Sumerian compositions means that any chronological approach to literary questions, such as the development of genres or correlation with historical processes or events, must be largely abandoned. (Reading Sumerian Poetry, 23)

It is possible that the story comes from the later period in Mesopotamian history, however, and given the loss in stature of the goddess in the myth, a later date is most likely. Although one may be tempted to locate this tale prior to Enki and Ninhursag, because she is known by her earlier name in this story, any such claims are untenable. The names of the goddess changed from story to story and are no aid in dating a particular text, save, perhaps, in those identifying Ninhursag as the earlier Damgalnuna.

The story opens with the younger gods weary from all their endless toil. They are forced to dig canals and harvest fields and engage in all kind of menial labor, which prevents them from greater work or any kind of leisure. They cry out to Enki to do something to help them, but Enki, represented as a supreme god, is resting after the effort of creation and will not wake. Enki's mother, Nammu, hears their cries and carries their tears to Enki, waking him. Enki is annoyed with the request but consents to his mother's wishes that he create beings who will ease the gods' burden. He asks her to work with Ninmah and other fertility goddesses to create human beings and give them life.

Once humans have been created, Enki holds a great banquet in celebration. All the older gods praise his wisdom, and the younger gods are relieved of their labors. Enki and Ninmah sit drinking beer together and eventually become quite drunk. Ninmah challenges Enki to a contest of sorts saying how the humans' bodies - Enki's design - may be either good or bad but their fates will be good or bad depending entirely on her will. Enki accepts her challenge saying, "Whatever fate you decide, good or bad, I will improve it."

Ninmah makes a man whose hands are weak and Enki improves his life by making him a servant to a king because he would not be able to steal. She then makes a man and blinds him, but Enki improves his life by giving him the gift of music and making him minstrel to the king. This same pattern goes on with Ninmah giving Enki greater and greater challenges, which he meets. She finally creates a being with neither penis nor vagina, but Enki finds a place for this creature as a eunuch to the king who will watch over him.

Ninmah is frustrated and throws her next lump of clay to the ground, but Enki picks it up and resumes the game, telling her how he will now fashion a creature and she must improve its fate as he has done. He creates a man afflicted in every area of his body and hands it to Ninmah. She tries to feed it, but it cannot eat, neither can it stand, walk, talk, or function in any way. She says to Enki, "The man you have fashioned is neither alive nor dead. He cannot support himself."

Enki objects, pointing out that she presented him with a number of challenging creatures and he was able to improve on them all. Ninmah's response to this is lost because the tablet is broken at this point, but when the story resumes, Enki is obviously the winner of the challenge, and the work ends with the lines, "Ninmah could not rival the great lord Enki. Father Enki, your praise is sweet!"

Although in this myth the goddess loses stature, she was still regarded as a powerful deity one could turn to in times of trouble and rely on for protection and guidance. Every myth, poem, or story Ninhursag appears in she is linked with life, caring, creation, and the role of the mother goddess.

Ninhursag, the Great Mother

Ninhursag also appears in The Atrahasis where she fashions humans out of clay mixed with the flesh, blood, and intelligence of one of the gods who sacrifices himself for the good of the many. The Atrahasis also gives Enki as the creator of humans who devises them as a means to relieve the gods of the burden of work. In this myth, when the Great Flood is released on the world by Enlil and humanity is destroyed, all the gods mourn but Ninhursag is specifically mentioned crying for the death of her children.

In some myths, presumed to be earlier works, she is the consort of Anu and co-creator of the world. In still others, she is identified with Kishar (also known as Ki), mother earth. Kramer notes how Ninhursag is listed last of the four creating deities, but how "in an earlier day this goddess was probably of even higher rank and her name often preceded that of Enki when the four gods were listed together" (122). She continued to be included in the list of the Seven Divine Powers, however, the oldest Sumerian gods: Anu, Enki, Enlil, Inanna, Nanna, Ninhursag, and Utu-Shamash. Each of these deities had their own specific gifts for people but Ninhursag, as the Great Mother, presided over all of humanity, commoner and king alike. She was primarily seen as the protector of women and children, who presided over conception, gestation, and birth but also held a position of high honor among the gods.

Scholar E.A. Wallis Budge notes how she "created the gods and suckled kings and terracotta figures of her represent her suckling a child at her left breast" (84). In ancient Mesopotamia, as elsewhere, the left side was considered feminine and "dark" while the right side was masculine and "light" (a concept familiar to anyone in the modern day acquainted with Reiki). Statuary representing the goddess always emphasizes the left side in one way or another. In the example Wallis Budge gives, it is a child at the left breast, but the symbolism could also be an uncovered left breast, raised left arm, or some other detail.

Ninhursag was worshiped at the city of Adab and was also associated with Kesh (as one of her names, Belet-ili of Kesh, confirms), not Kish, as is often incorrectly cited. She was further honored with temples at Ashur, Ur, Uruk, Eridu, Mari, Lagash, and many other cities throughout Mesopotamia for thousands of years. Kramer notes how "the early Sumerian rulers liked to describe themselves as 'constantly nourished by Ninhursag with milk.' She was regarded as the mother of all living things, the mother-goddess pre-eminent" (122).

The people would worship the goddess as they did any other Mesopotamian deity through private ritual and sacrifices/donations made to the temple. There were no temple services in which congregants gathered for weekly worship, but the many festivals held throughout the year provided opportunity for expressing one's devotion publicly.

In the second millennium BCE, as noted, feminine deities experienced a loss in status as the male gods of the Amorites of Babylon under Hammurabi took precedence. Following Hammurabi's reign, from c. 1750 BCE onwards, male deities would dominate the pantheons of Mesopotamia, and even after the Amorites were defeated, this same paradigm continued. The immensely popular goddess Inanna/Ishtar would become secondary to male gods like the Assyrian Assur, and the powerful goddess Ereshkigal, who ruled the underworld, would be given a male consort (Nergal) to reign with her.

In time, the left side associated with the goddess concept would be connected with darkness and evil as can be seen in the word 'sinister,' which originally was Latin for 'left' but came to signify 'threatening,' 'evil,' and similar concepts long before the word appears with such connotations in Late Middle English (c. 1375-1425 CE). The practice of wearing a wedding ring on the left hand originated in Rome to ward off evil powers associated with the left.

It is no accident that, in the Hebrew legend of Lillith, the rebellious first wife of Adam emerges from his left side to later fly away from paradise with her demons; the goddess figure and her symbols had to be inverted and charged with negative associations for the male gods to achieve dominance.

Ninhursag experienced this same decline as the other goddesses, and by the time of the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BCE, she was no longer worshiped. Her influence is considered significant, however, in the development of later goddesses as she has been associated with Hathor and Isis of Egypt, Gaia of Greece, and Cybele of Anatolia, the later Magna Mater of Rome, who would contribute to the development of the figure of the Virgin Mary.