Ninja (aka Shinobi) were the specialised assassins, saboteurs, and secret agents of medieval Japanese warfare who were highly-trained proponents of the martial arts, especially what later became known as ninjutsu or 'the art of the ninja'. These special forces were adept at disguise, deception, and assaulting enemy positions and strongholds, usually at night when they moved like shadows in their traditional dark clothing. Employed from the 15th century CE onwards, ninjas, because of their lengthy secret training in specialised schools and mysterious anonymity, have acquired a perhaps exaggerated reputation for fantastic feats and weapons play, which makes them perfect characters for many modern comic books and computer games.

Martial Arts & Ninjutsu

In medieval Japan, there were no fewer than 18 individual martial arts (bugei or bujutsu). Besides the more familiar ones which are still practised today such as judo, jujutsu and kendo, there were those involving horsemanship and swimming. One of the 18 was the art of the ninja or ninjutsu, which developed during the Edo Period (1603-1868 CE). However, ninjas as military special forces had been in operation since the 15th century CE and the Warring States Period (aka Sengoku Jidai, 1467-1568 CE) when the factious infighting that beset Japan required reconnaissance, intelligence and spying in order to ascertain who exactly one's enemies were or might be in the near future.

A ninja, then, had two main roles: as an assassin and as a spy to gather intelligence on enemy movements and plans. For both, they employed disguises and learnt the art of deception. The real identity of successful ninjas was, of course, concealed to ensure their own safety and continued usefulness in future operations. Ninjas were also used as forward scouts and to generally cause as much disruption as possible behind enemy lines during nighttime commando raids.

Besides organised bands of ninjas, there were many freelance ninjas who offered their services to the highest bidder in the unsettled times of 15th and 16th century CE Japan. Crafty leaders sometimes employed ninjas to infiltrate the ninja bands of the enemy. In order to make sure ninjas within a group were who they should be passwords were used at random. A ninja was supposed to stand whenever they heard the password and anyone left seated was thus exposed.

The tactics of subterfuge, ambush and trickery, as well as their use of projectile weapons, meant that ninjas did not enjoy the high reputation that samurai warriors, perhaps not entirely fairly, acquired for being chivalrous and courageous. By the Edo Period and the peace which followed from the Tokugawa domination of Japan, ninjas were no longer required in such numbers and so the formal martial art of ninjutsu developed to continue their traditions. Illustrated manuals were written as guides for would-be practitioners, the most famous being the Bansen shukai, compiled by Fujibayashi Samuji in 1676 CE.

Training

The earliest approach to ninja training was taken by particular families of samurai warriors who passed on their skills from father or master (sensei) to son. These became the famous ninja families and explain why certain localities established long traditions of producing the specialised warriors. From childhood, a future ninja would learn to ride, swim, and handle weapons of all kinds. From the 15th century CE, ninjas were being trained in special camps which might involve entire villages. Some schools became especially famous such as the Iga and Koga schools. As leaders did not want rivals copying their tactics, all training was done orally lest written records fall into the wrong hands.

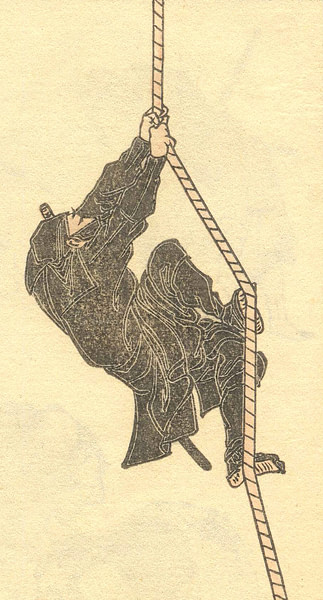

A ninja was trained to be physically fit and nimbly athletic; jumping from heights and across moats and other obstacles was a particularly useful skill and is probably the origin of the legends involving flying ninjas. In addition, they were also trained to work in acrobat-like teams so that they could use each other to climb greater heights. Ninjas could also throw grappling hooks with precision, scale up and down ropes and collapsible ladders, and enter places closed to less-skilled operatives. Ninjas could create spyholes using pocket folding saws and gouging tools. They could impede pursuers by throwing down makibishi (caltrops - metal clusters of points). Ninjas were taught such useful skills as concealing oneself in various terrains, survival skills to live off the country, how to read topography and maps, understand indications of weather changes, use explosives, securely tie up captives, mix poisons, destroy a building by fire, and, for when things did not go well on a mission, the arts of escape and medicine.

Ninja Costume

Although no medieval texts actually describe in detail a ninja's outfit, the most usual depiction in Japanese art from the early 19th century CE has them clad all in black. This would seem to be the most obvious colour choice because most of their work was done at night. It is also a convention of Japanese performance arts that a character wears black to show the audience that he or she is invisible. However, ninjas did sometimes wear chain mail or armour of metal plates sewn onto fabric and, as they were meant to blend into their surroundings, they sometimes wore camouflage, disguises (as beggars, monks or wandering musicians, for example) and even the costume of their enemies when required. The classic ninja outfit consists of trousers, gaiters, a jacket, a belt, a head cover and a face cover all in soft material that did not impede movement and which had no dangling parts that might catch on anything. Soft shoes were worn which were more like socks (tabi) with the big toe divided from the rest of the toes and a reinforced sole; simple knotted-rope sandals (waraji) might be worn over these to provide a better grip for climbing.

Ninja Weapons

The main weapon of a ninja was his sword or katana, perhaps a little shorter and less curved than those used by other warriors as a ninja might find himself in a restricted space like a narrow castle corridor. So as not to impede his movements a ninja typically wore his sword not at the belt but diagonally across his back. The handle guard (tsuba) was useful because if one leaned the sword against a wall it could be used as a step, and, by putting a foot through the customary cord of the scabbard, the sword could then be lifted up and not left behind.

Besides being adept at using the more usual weapons of Japanese warfare - the sword, spear, halberd and bow - ninjas had their own particular and highly specialised weapons. Throwing knives were a common weapon in medieval Japan and ranged from daggers to curved blades, but the most frequently associated with the ninja is the multibladed steel throwing star or shuriken. The typical shuriken was 20 cm in diameter and had at least four points which made them useful, light weapons which did not impede movement. There were even ninja schools which specialised in the use of throwing stars such as those in the regions of Sendai, Aizu, and Mito.

Ninjas were especially associated with the kusarigama or crescent-shaped sickle. The sickle blade was attached to a wooden pole which had a 2-3 metre (6.5-10 ft) long chain with a weight at the other end. The ninja version, the shinobigama, had a much shorter pole and a smaller blade than usual, which was kept in a scabbard when not in use. The ninja would hold the end of the chain and swing it so that he could damage the weapon of his opponent or knock it from his hands or trip him up with the chain.

Another specialised weapon was small metal pins (fumibari or fukumibari) which a ninja placed in their mouth and spat at the enemy, aiming for their eyes. Some of the more personalised weapons included metal knuckledusters (tekagi) and hand claws (hokode) which could be useful for climbing, too.

The bombs used by ninjas were of two main types - a paper- or wicker-covered package which could release smoke or poisonous gas when lit and a hard-cased bomb with an iron or ceramic cover. Both types used gunpowder and might include shrapnel; both were also small enough to be used as hand grenades. They were lit using cord fuses and a tinder box which was typically lacquered to make it waterproof.

When they did not have weapons, a ninja could resort to their formidable martial arts skills such as aikido which uses an opponent's momentum to throw and disable them by applying pressure at key weak points such as wrists and elbows. And they learnt kendo which uses a bamboo sword (although in ancient Japan it more often had a metal blade) so that even a wooden pole could become a deadly weapon in the skilled hands of a ninja.

Legacy

In the myths and legends which have been written about ninjas since the medieval period, these highly-trained professionals are often given extraordinary, even superhuman abilities. Some writers believed ninjas could fly or transform themselves into creatures like spiders and rats - significantly, those sorts of pests admired for their agility but not much-loved by anyone. They were credited with other incredible feats which ranged from removing the pillow from beneath a sleeping enemy or assassinating a warlord from below while he sat on his toilet. These stories are likely exaggerations, but it is true that many a careful warlord protected himself from any would-be assassin by providing their castle with anti-ninja devices like terribly creaking floorboards, confusing layouts, revolving walls, and hidden trapdoors.

Ninjas remain a popular character element in films, comic books, and computer games in Japan, and the martial art of ninjutsu is still practised today. There are, too, many museums devoted entirely to the history of ninjas, particularly, of course, in Japan, and chief amongst these being the castle of Iga-Ueno in Mie Prefecture, one of the ancestral homes of the ninja warriors.