Obsidian is a dark volcanic glass which provides the sharpest cutting edge available in nature. Ancient Mesoamerican cultures greatly esteemed the properties of obsidian, and it was widely traded across the region. Obsidian was used to create tools, weapons, and, when polished, for mirrors and as a decorative inlay in anything from jewellery to ritual masks.

Properties & Trade

Obsidian (chemical name: silicon dioxide) is a type of volcanic glass created when hot lava cools and solidifies so quickly that crystals have no time to form in it. Made of a variety of chemical compositions, most obsidian is silica based. Obsidian is usually black but can come in a range of shades such as blue-black, peacock, mahogany, and even much lighter, greenish ones. These colour variations are caused by the presence of minerals like hematite or minute bubbles of gas. It can also come with white flecks of cristobalite (snowflake obsidian).

Despite the lack of rarity of the raw material, worked pieces of obsidian were greatly prized by all Mesoamerican cultures from the Olmecs to the Aztecs (aka Mexica), and so it was one of the earliest and most commonly traded goods. It was particularly valued for the super-sharp cutting edge that carefully chipped obsidian can provide, as sharp as any modern razor blade (indeed, some surgical procedures today involve the use of obsidian-edged scalpels). Obsidian is easily thinned by striking it with a harder stone to remove flakes along conchoidal fractures (which appear shell-like). Its use in weapons and tools of various kinds has led the historian M. E. Miller to describe obsidian as "the 'steel' of the New World" (11). The material was also esteemed for its smooth texture and unusual dark vitreous lustre when polished, which ancient Mesoamericans usually achieved using abrasive sand.

As with other sought-after materials like jade and turquoise in Mesoamerica, the more unusual varieties of obsidian were the most highly valued. A rare olive-green type of obsidian was obtained from the Sierra de las Navajas mines at Pachuca, and nearby Tula (aka Tollan) became a major trading centre for obsidian. Tula was the capital of the Toltec civilization which flourished in central Mexico between the 10th and mid-12th centuries. The number of obsidian workshops at Tula has led to historians estimating that around 40% of Tula's total population of 30–40,000 people was engaged in working obsidian for the city's needs and for trade.

Mesoamerican trade in obsidian, though, goes back much earlier than the Toltecs, with evidence it was exchanged in the second millennium BCE during the period often called the Early Formative. Major deposits of Mesoamerican obsidian besides Pachuca came from the highlands of Jalisco (western central Mexico) and the highlands of Guatemala (El Chayal and San Luis Jilotepeque). From these highland deposits, obsidian was transported via canoes along waterways to the wider region. Trade was not always carried out by city-states or elites, craftworkers themselves sometimes arranged the procurement of unworked obsidian, as can be seen at sites like Xochicalco, which flourished between c. 700 and c. 900 CE. On the other hand, we know that at some contemporary sites in western Mexico (the Tequila valleys) obsidian jewellery was controlled by the ruling elite and that at neighbouring Tarascan sites, the production of obsidian blades was controlled by the state. Clearly, there was a division in value and control between unworked obsidian and finished articles associated with power like elite jewellery and weapons.

Uses

Obsidian was often worked from a raw piece into a multi-faceted cone-like form from which multiple blades or shards could be easily split off. As a cutting edge, obsidian was second to none, but it does have the fatal flaw of being easily shattered. Teotihuacan in central Mexico was at its height from 375 to 500 CE, and there, worked obsidian blades were used for various types of weapons and tools, as here explained by the historian D. M. Carballo:

Teotihuacan's soldiers were armed with obsidian-tipped darts, short spears thrown with an atlatl or spear-thrower, obsidian knives, and wooden clubs. Within the city some obsidian workshops were located in apartment compounds where primarily utilitarian tools were fabricated, whereas at least one workshop was located near to the Moon Pyramid and specialised in the production of weapons (dart points and knives) as well as ceremonial items of the type that were deposited as consecratory offerings and exported as far away as certain Maya cities. Domestic workshops appear to have been organized as independent commerce undertaken by extended families, but the workshop of the Moon Pyramid precinct would have been overseen by state functionaries, and the finished weapons may have been stored in state armories. (41)

Effigy figures of obsidian have been excavated at Teotihuacan of both humans and animals, especially serpents. Sculptures and relief carvings of deities at Teotihuacan were often inlaid with obsidian, usually reserved for features like eyes, the chest, and jewellery. Black and obsidian were associated with night, death, and the underworld, hence the use of obsidian for elements of funerary items. An example is the obsidian lid of a spectacular travertine urn containing the cremated remains of a single male, which was discovered at the base of the Templo Mayor at Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City). The remains may have belonged to a ruler of the Aztecs, the last great Mesoamerican civilization.

As a semi-precious material, highly polished obsidian was used in the jewellery of Mesoamerican society's elite. As beads or inlay, it was worn as necklaces, bracelets, anklets, finger rings, earplugs, lip piercings, and as an element of larger pieces like belts, pectorals, and headdresses. Tula craftworkers, whose skills were legendary to the later Aztecs, managed to make wafer-thin pieces of obsidian jewellery, which was often faced with a more precious material like gold or turquoise.

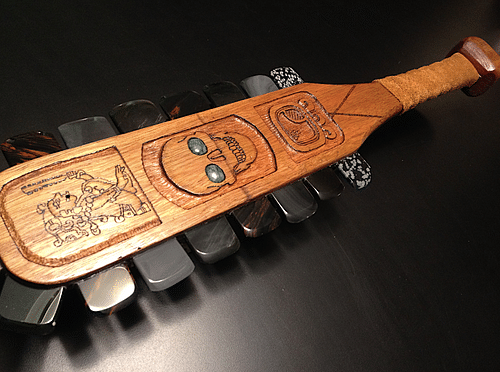

The Aztecs, like all those before them in the region, used obsidian (which they called itztli) for weapons such as knife blades, arrowheads, spear blades, dart tips, and axe heads. One particular Aztec weapon was the combination of sword and club known as a macuahuitl. Shaped like a long paddle made of wood, the worked obsidian blades were inserted on both sides of its length. Obsidian blades must have caused some horrific injuries, and it is no wonder that Mesoamerican warriors strived to protect themselves. Round shields of wood or cane strengthened with leather were used (chimalli) and sometimes leather helmets. Body armour (ichcahuipilli) was also worn and made from quilted cotton, which was soaked in salt water to make the garment stiffer and more resistant to enemy blows. This armour was so effective even Spanish conquistadors used it in their encounters with obsidian-armed indigenous armies.

Sacred Associations

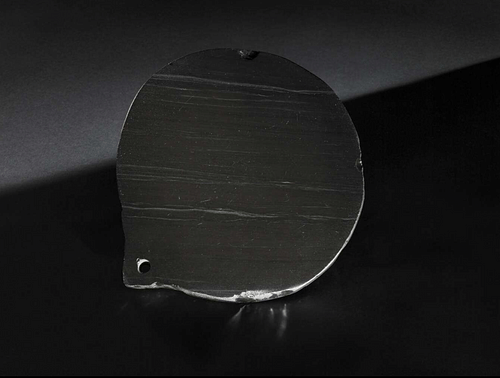

When highly polished, obsidian was used to create mirrors throughout the history of Mesoamerica, although other materials were used, too, such as polished pyrite. They were often given wooden frames or an outer edge of exotic feathers and pierced with a single hole so that a cord could be put through them. Mirrors were not simply items to check one's reflection in but were given special associations. The Aztec and Toltec god Tezcatlipoca was thought to be the very personification of a polished obsidian mirror; indeed, his name in the Nahuatl language means 'Smoking Mirror' (the reflective properties of a smoking fire were often equated with those of a mirror). Tezcatlipoca was a creator god and a bringer of good and evil. As he represented the duality of change through conflict, a mirror was an entirely suitable emblem for him with its real and reflected surface. Similarly, the god's all-seeing omnipresence was well represented by an all-seeing, truth-seeking mirror. It was believed the god regarded humanity only as a reflection in his mirror, a reminder of the latter's mortality. It was believed that the god could use his two-sided mirror to not only divine the future but to "reveal the true nature of things, including one's soul (Carballo, 179). It is interesting to note that examples of surviving obsidian mirrors have often been polished on both sides, perhaps in imitation of Tezcatlipoca's own special mirror. Representations of Tezcatlipoca in art frequently show the god with an obsidian mirror at the back of his head or with one at each of his temples and sometimes with another as a replacement for one of his feet.

Obsidian tools played an important part in certain Mesoamerican-wide rituals like bloodletting. A form of mild self-sacrifice, bloodletting was in imitation of the sacrifice the gods had made in order to create humanity. Obsidian bloodletting tools were often buried in tombs alongside the deceased, both males and females.

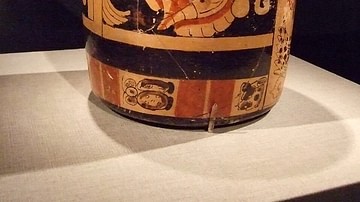

Obsidian appears in writing systems. For example, the city of Itzteyocan was represented by a combination of a road, a stone, and a black obsidian blade. Obsidian pieces were also used as a material upon which to write or incise gods, symbols, and patterns. Several pieces excavated from beneath a stela at Maya Tikal in Guatemala have been incised to represent specific gods. The burial of incised obsidian pieces beneath stelae is not unique to Tikal and was a practice conducted throughout the central Maya area.

The Cakchiquel Maya communicated with a sacred obsidian stone, which was perhaps regarded as an oracle, which they called Chay Abah. The historian M. Miller suggests that the Chay Abah may well have been a polished mirror. Shamans also used mirrors – either in the form of bowls of water or a polished material like obsidian – to see into both the past and future and to communicate with the dead. It was believed in many Mesoamerican cultures that a mirror – because one could look into it but not through it – was somehow an access point to another, spiritual world. Just as the gods gazed upon humanity through the reflections of a mirror, so, too, gifted humans and, particularly, community leaders, could see the gods reflected in a mirror and so gain hints as to what they planned for the future.

The power of an obsidian mirror to tell the future forms part of a legend involving the last true Aztec ruler Motecuhzoma II (aka Montezuma, r. 1502-1520). Local fishermen one day came across an extraordinary bird similar to a crane but with a mirror on its head. The oddity was duly presented to Motecuhzoma, and when he looked into the mirror he was surprised to see for just a moment a starry night sky and then several warriors riding deers. Whether these warriors represented Spanish conquistadors on horseback (an animal then unknown to Mesoamericans) or some other future event or whether this vision actually happened at all or is an example of history being written after the event, we cannot know, but it does, at least, reveal the powers Mesoamericans were willing to give to highly polished obsidian. Mirrors, obsidian or otherwise, were regarded as such valuable and significant items they were worn as a sort of jewellery or status symbol, particularly by rulers, and this may explain why the fishermen were so keen to present their 'mirror-bird' to Motecuhzoma.

It seems the appeal of worked obsidian crossed cultures and appealed to foreign rulers, too, since Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598) was said to have owned several Mesoamerican-made obsidian mirrors. The reverence given to obsidian mirrors was difficult to eradicate for Spanish priests in New Spain (as the region became known), which perhaps explains why they tolerated the frequent addition by converted Mexicans of an obsidian mirror to atrial crosses in and around colonial churches, some of which are still standing today with their obsidian mirrors still in place.