Oedipus the King (429-420 BCE), also known as Oedipus Rex or Oedipus Tyrannos ('Tyrannos' signifies that the throne was not gained through an inheritance) is the most famous surviving play written by the 5th-century BCE poet and dramatist Sophocles. The play is part of a trilogy along with Antigone and Oedipus at Colonus.

The plot - an old myth already known to most of the audience - was simple: a prophecy claiming he would kill his father and lie with his mother forces Oedipus - whose name means 'swollen foot' after his ankles were pierced as a child - to leave his home of Corinth and unknowingly travel to Thebes (his actual birthplace). En route he fulfills the first part of the prophecy when he kills a man, the king of Thebes and his true father. Upon arriving in Thebes, he saves the troubled city by solving the riddle of the Sphinx, then he marries the widowed queen (his mother) and becomes the new king. Later, when a plague has befallen the city, Oedipus is told that to rid the city of the plague he must find the murderer of the slain king. Unknowingly, ignorant of the fact that he was the culprit, he promises to solve the murder. When he finally learns the truth, he realizes he has fulfilled the prophecy; he blinds himself and goes into exile.

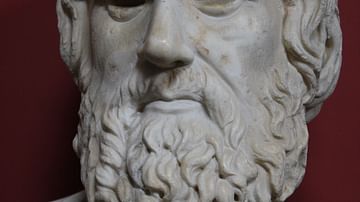

Sophocles

Sophocles (c. 496 BCE - c. 406 BCE) was born to a wealthy family in the deme or suburb of Colonus outside the heart of Athens. Besides being an author, he was extremely active in Athenian public life, serving as a treasurer in 443-42 BCE and a general 441-40 BCE. When he was in his eighties, he was named a member of the group of special magistrates assigned to the dubious task of organizing both financial and domestic recovery in 412-11 BCE after the disastrous defeat at Syracuse. He had two sons; Iophon by his wife Nicosrate and Ariston (also called Sophocles) by his mistress Theoris. Both sons would eventually become playwrights. Among his close friends were the historian Herodotus and the statesman Pericles.

Although active in Athenian political circles, his plays rarely contain any references to current events or issues - something that makes the dating of his plays difficult. Classicist Edith Hamilton wrote that he was a passionless, detached observer of life. In her book The Greek Way, she said that the beauty of his plays was in their simple, lucid, and reasonable structure. He was the embodiment of what we know to be Greek. She wrote that “… all definitions of the Greek spirit and Greek art are first of all definitions of his spirit and his art. He has imposed himself upon the world as the quintessential Greek, and the qualities pre-eminently his are ascribed to all the rest” (198-199). She added that he was conservative in politics and believed in the established order of things, even in theology. Author David Grene in his translation of Oedipus the King said that his plays had tightly controlled plots with complex dialogue, character contrasts, an interweaving of spoken and musical elements, and the “fluidity of verbal expression.”

Main Characters

Greek tragedians performed their plays in outdoor theaters at various festivals and rituals in competitions. The purpose of these tragedies was to not only entertain but also to educate the Greek citizen, to explore a problem. Along with a chorus of singers to explain the action, there were actors, often three, who wore masks. Sophocles' contemporaries included Aeschylus, author of Prometheus Bound, and Euripides, author of Medea. At the festival of Dionysius, Sophocles won 18 competitions, while Aeschylus won 13, and Euripides only five. Few accurate dates are known for his plays; Oedipus the King was probably written in the mid-420s BCE. This estimate is based on his reference to a plague that beset the city during Oedipus's time on the throne. Oddly, while it was one of his most popular plays then and now, it did not win first prize.

The play's characters are few:

- Oedipus, the king

- Creon, his brother-in-law

- Teiresias, an old blind prophet

- Jocasta, Oedipus' wife and mother

- two messengers

- a herdsman

- a priest

- and, of course, the chorus.

Plot Summary

The play opens with the city of Thebes in turmoil, beset by a plague. A priest speaks to Oedipus:

A blight is on the fruitful plants of the earth, a blight is on the cattle in the fields, a blight in on our women that no children are born to them… (Grene, 74)

He reminds the king that he had freed the city from the tribute paid to the Sphinx, and now the city pleads for him to find some way to rescue the city and “set it straight.” Oedipus replies that he understands the plight of the people and has sent his brother-in-law Creon to the temple of Apollo (often referred to in the play as King Phoebus) to find an answer. Upon returning to the city, Creon requests to speak to the king in private, but Oedipus replies: “Speak it to all, the grief I bear, I bear it more for these people than for my own life” (77). To rid the city of the plague they must find the murderer of King Laius. Knowing little about the former king's death, Oedipus listens to the details of the murder, a crime supposedly committed by robbers. He vows to find the murderer:

Whoever he was that killed the king may readily wish to dispatch me with his murderous hand: so helping the dead king I help myself. (79)

Oedipus speaks to the audience, begging that if anyone knows the murderer to come forward, promising that he has no punishment to fear, only exile. However, he invokes a curse:

… whether he is one man and all unknown, or one of many - may he wear out his life in misery to miserable doom. (82)

He is told of a local blind prophet, Teiresias, who often sees what Apollo sees and might help him solve the murder. However, after the prophet arrives, he is afraid to speak, fearing for his life if he tells the truth. Oedipus pleads, “You know of something but refuse to speak. Would you betray us and destroy the city?” (86) To try and force him to speak, Oedipus accuses him of being part of a plot. Reluctantly, the old prophet relents, telling Oedipus that he, himself, is the murderer. Oedipus is irate, threatening Teiresias. The old man replies that Oedipus taunts him “with the very insults which everyone soon will heap upon yourself” (89). The king questions if this accusation comes from him or Creon. The old prophet replies that Creon is not to blame. The old prophet then inquires of Oedipus if he knows who his parents are, adding that a “curse from father and mother both, shall drive you forth out of this land, with darkness on your eyes” (91).

Oedipus and Creon meet to talk. Immediately, Oedipus threatens his brother-in-law, calling him a traitor and plotting against him. In defense, Creon asks if he is to be banished. When Jocasta arrives, the king tells her that her brother is plotting against him, but she replies in defense, “… what was it that roused your anger so?” (104) He tells her that Creon accuses him of killing her husband, the king. She responds that he should not concern himself with the matter and tells him of the prophecy of the oracle and the death of her husband:

… it was fate that he should die a victim at the hands of his own son … (b)ut see now, he, the king was killed by foreign highway robbers at a place where three roads meet. (105)

With his curiosity aroused, Oedipus asks about the murder: How long ago was it? What did he look like? How old was he? She tells him of the only survivor, an old servant who was sent away. Oedipus asks to speak to the old man, and if their stories are the same, he will be free of any guilt.

Oedipus then relates the story of his own departure from Corinth. He had been called a bastard at a dinner party held by his parents, the king and queen. Although his parents denied the accusation, he soon learned that a prophecy fated him to murder his father and lie with his mother. To avoid fulfilling the prophecy, he fled the city only to come to a crossroads where he encountered a carriage. A dispute ensues and he ends up killing the carriage's occupant and the driver. “I killed them all.” He asks of Jocasta, “Was I not born evil? Am I not utterly unclean?” (110)

A messenger arrives to tell Oedipus that his father, the king of Corinth is dead. Oedipus realizes that the old prophecy was wrong.

They prophesied that I should kill my father. But he's dead and hidden deep in the earth, and I stand here who never laid a hand or spear near him… (116)

However, he is confused and not completely relieved, still fearing that the prophecy may be proven to be true. The messenger adds that King Polybius was not Oedipus' real father, for he had received a baby - Oedipus - from a shepherd and given it to the king. Oedipus realized that this shepherd was the same man who had been sent away by Jocasta. To help appease the king's anguish Jocasta tells Oedipus that she hopes the gods keep him from finding out who he really is.

The old herdsman arrives to speak to Oedipus. After the king pressures him, he reluctantly relates the story of how he had pitied the baby that came from the house of Laius and given it to the messenger. After hearing the herdsman's confession, Oedipus is beside himself, begging for a sword so he could kill his wife, his mother. Speaking to the chorus, a second messenger arrives and tells that the audience that Jocasta is dead; she had committed suicide. When Oedipus enters her room, he finds her hanging with a twisted rope around her neck. He tore the brooches from her robe and stabbed himself in his eyes, repeatedly. Blinded, he begs to be shown to the men of Thebes as his father's killer. He laments: “Why should I see whose vision showed me nothing sweet to see?“ (134) He proclaims that he is godless and a child of impurity. “If there is any ill worse than ill, that is the lot of Oedipus” (135). Creon comes to him but not to laugh, only to ask what he could do. Oedipus asks to give Jocasta a proper funeral, and for himself, to be driven out and live “away from the city.”

Legacy & Oedipus Complex

Oedipus the King was not only staged throughout antiquity but is still performed to this day and is required reading in many schools. It survived as the model for plays by such noted authors as Seneca, Dryden, and Voltaire. The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud even coined the phrase “Oedipus Complex” to describe the developmental phase when one may experience a desire for one's parent of the opposite sex. David Grene wrote that Oedipus serves as “a metaphor for every human being's quest for personal identity and self-knowledge in a world of ignorance and human horrors” (11).