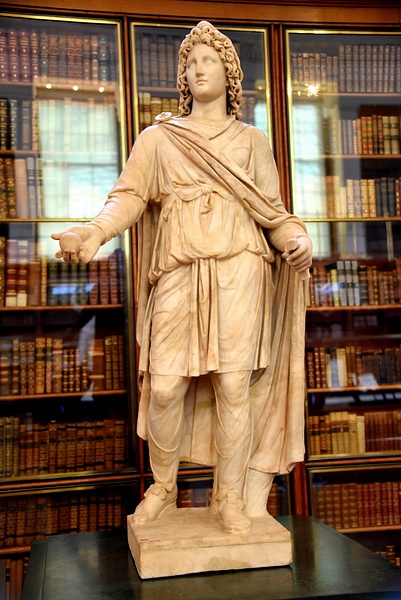

Oenone was a nymph in Greek Mythology, the daughter of the river god Cebren and sister of the nymph Asterope/Hesperia. She was given the gift of prophecy by Rhea (mother of the gods) and the gift of healing by Apollo. Her name comes from the Greek word oinos, for 'wine'. She lived on Mount Ida where she met the young prince Paris of the city of Troy when he was a shepherd, unaware of his own noble birth.

The two were married and enjoyed their life together until Paris was chosen by Zeus to choose between the goddesses Athena, Aphrodite, and Hera as the most beautiful and chose Aphrodite who promised him the most beautiful woman in the world if he chose her. That woman was Helen of Sparta, the wife of Menelaus, king of Sparta, and Paris left Oenone to voyage to Sparta where he met Helen and carried her off; thus igniting the Trojan War as depicted in Homer's Iliad.

Oenone's story, like the death of Achilles, does not appear in the Iliad but comes from later sources which also developed the tale of the death of Paris. Her abandonment by Paris, efforts to win him back from Helen, and tragic death inspired later works in art and literature, most famously by Ovid (l. 43 BCE-18 CE) and the English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson (l. 1809-1892 CE) though her story was also developed by many others. She is always presented sympathetically as a woman in love with an unappreciative and shallow young man who has no capacity for returning her love.

Her name has been translated as 'Lover of Paris' without regard to etymological roots. The Greek island of Aegina was originally known as Oenone or Oinone, 'Island of Wine', due to the excellence of the wine made there, before the King Aeacus renamed it after his mother. It is generally held that the island's original name had nothing to do with the Greek nymph.

Paris' Birth, the Prophecy, & Oenone

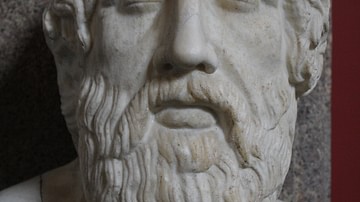

Setting aside considerations of the historicity of the Iliad, the creation of the literary character of Paris is credited to the Greek poet Homer (c. 8th century BCE). Afterwards, other writers developed Homer's story and characters in their own works, adding to the richness of the story, and Paris' character is among the most-often referenced.

According to Homer and these later tales, Paris was among the many sons of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy. Just before he was born, Hecuba dreamed she gave birth to a torch of bright flame. This dream was interpreted by Aesacus, another of Priam's sons and a seer (who also loved, and lost, Oenone's sister Asterope). Aesacus understood the dream to mean that the child would bring ruin upon Troy and should be killed. Once Paris was born, neither his father nor mother could bring themselves to harm him and so Priam gave him to his trusted herdsman, Agelaus, to remove from the palace and dispose of.

Agelaus could not bear to harm the boy either, but also could not bring him back to Priam, and so left him exposed to die on Mount Ida. When he returned nine days later, he found the infant thriving, having been suckled daily by a she-bear. Agelaus then brought the baby back to his own house to rear as his own.

Paris grew up as a shepherd on Mount Ida, presumably the son of Agelaus, but his noble heritage was apparent in his great beauty, courage, and natural intelligence. After he had driven off a group of thieves, he was known as Alexandros (“defender of men”), the name most commonly used for him by later writers. He attracted the attention of Oenone who fell in love with him, even though he was a lowly shepherd and she a nymph and the daughter of the river god, and he swore his eternal love for her, promising he would never leave. The two were married, Oenone bore Paris a son, Corythus, and the family lived happily on Mount Ida.

Some years later, Paris took one of the bulls from Agelaus' herd to Troy as an offering in a grand celebration, not knowing this event was a commemoration of his own “death” consisting of funeral games in his honor. He took part in these games and won the bull he had brought as well as the admiration of many but some, including his own brothers, berated him for his presumption since he was only a shepherd and yet had managed to somehow do better than his superiors and even better even than the god Ares who had participated in a bull's form. Before they could attack him, however, he was identified as the supposedly dead prince by his sister Cassandra who had the power of prophecy.

Oenone, Corythus, and Paris then moved to Troy and were welcomed into the royal family. Scholar Robert E. Bell writes:

The brief stay among the princes and princesses of Troy must have been difficult for [Oenone] since she, a simple and unassuming nymph, was out of place among her urban in-laws. (330)

According to some sources, the three remained in Troy while, in others, they returned to Mount Ida. Oenone is said to have used her powers to make people forget about the prophecy surrounding Paris and accept him as a long-lost son. No account of how Hecuba or Priam might have honestly reacted to the return of the son they thought they had sent to be killed exists.

Judgment of Paris & Betrayal

The Judgment of Paris is referenced casually by Homer in the Iliad, suggesting his audience would already have been acquainted with the story and it needed no elaboration. The early sources of the tale have been lost, if they were ever written down, and the extant story comes from later writers.

The story tells of a great banquet held by Zeus, the king of the gods, to celebrate the marriage of Peleus and Thetis (the future parents of the hero Achilles) but did not invite Eris, the goddess of discord, who Zeus feared would have ruined the party. Eris was insulted and arrived at the banquet anyway, throwing a golden apple into Zeus' hall with the words, “For the Fairest” written on it.

The goddesses Athena, Aphrodite, and Hera all claimed the apple as theirs and, when none of them would relinquish it, asked Zeus to judge between them. Zeus, refusing to choose between the three, referred the matter to Paris who had done so well at the games of Troy that he had even bested Ares. He had his trusted messenger-god Hermes guide the three goddesses to Mount Ida where they bathed in a spring near to where Paris who, although now recognized by the court of Troy as the long-lost prince, had returned to tending the livestock of his foster-father Agelaus (though, in some sources, this tale comes before he is recognized).

They asked him to judge between them who was the fairest. Hera offered him power in the form of kingship of all Europe and Asia if he chose her. Athena promised him wisdom and martial prowess. Aphrodite assured him he would have the most beautiful woman in the world. Paris chose Aphrodite who rewarded him with the love of Helen of Sparta – a woman he had not yet met – the wife of the king Menelaus.

When Helen, who had been courted by many exceptional suitors, married Menelaus, the king of Ithaca, Odysseus, told her father Tyndareus that all would swear to defend the marriage. Paris told Oenone he had to travel to meet with Menelaus on a matter of diplomacy between Troy and Sparta though, actually, it was to claim the prize Aphrodite had promised him.

Oenone's Devotion & Death

Oenone had been given the gift of prophecy by Rhea and so foresaw the results of Paris' actions in Sparta and tried to talk him out of going. Paris refused, however, and so Oenone told him that, should he be wounded in his venture, he should return to her for only she could heal him owing to the power given her by Apollo.

Once he arrived at Sparta, Paris abducted Helen (or, according to other sources, she fell in love with him and left willingly), and Menelaus called in Odysseus' pledge to her father for the former suitors and his friends to defend his marriage. These alliances launched the one thousand ships which left Greece to bring Helen back and defend the honor of Menelaus, resulting in the ten-year Trojan War.

Paris brought Helen back to Troy where their marriage was celebrated. Oenone, abandoned, vowed revenge on her faithless husband, and when the Achaean Greeks arrived, she had Corythus guide them to Troy. As the war wore on, she sent Corythus again to seduce Helen and prove to Paris that his new wife was faithless and hardly worth his affection. Paris found Corythus in bed with Helen and, not recognizing his adult son, killed him.

Paris, the cause of the war, was the weakest participant in the conflict whose sole achievement was killing the Achaean hero Achilles by firing the arrow which struck his heel, the only part of his body unprotected by the promises of all the elements and aspects of the earth which had sworn to his mother to defend him. Paris was afterwards struck by the arrow of the Achaean hero Philoctetes and was carried to Mount Ida to be saved by the potions of Oenone.

She, hurt by his betrayal of her with Helen of Sparta, refused to help him and he was carried back to Troy where he died. Oenone repented of her decision and rushed to Troy with aid but arrived too late. In her grief and regret, she flung herself onto his funeral pyre and died. Two alternate ends of Oenone's life claim she hanged herself or threw herself off a cliff near Troy.

Oenone in Later Sources

Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote a famous poem about Oenone in 1833 CE which sparked widespread interest in the legend in the 19th century CE and inspired artists of the Romantic period to further pursue the themes of the story. Writer since that time have picked up on this theme, which knows no boundaries of time or particular culture, to explore relationships between men and women.

Oenone's story is related through the works of a number of ancient writers such as Bacchylides (l. 5th century BCE), Lycrophon (l. 3rd century BCE) and the poet and grammarian Parthenius of Nicaea (d. 14 CE). The earlier writers' mentions of Oenone are fragments while Parthenius' account remains intact in his Erotica Pathemata (Sorrows of Romantic Love) which features tragic love stories from history or mythology. Oenone's tale by Parthenius is given as follows:

When Alexandros [Paris], Priamos' son, was tending his flocks on Mount Ida, he fell in love with Oinone (Oenone) the daughter of Kebren (Cebren): and the story is that she was possessed by some divinity and foretold the future, and generally obtained great renown for her understanding and wisdom. Alexandros took her away from her father to Ida, where his pasturage was, and lived with her there as his wife, and he was so much in love with her that he would swear to her that he would never desert her, but would rather advance her to the greatest honour. She however said that she could tell that for the moment indeed he was wholly in love with her, but that the time would come when he would cross over to Europe, and would there, by his infatuation for a foreign woman, bring the horrors of war upon his kindred. She also foretold that he must be wounded in the war, and that there would be nobody else, except herself, who would be able to cure him: but he used always to stop her, every time that she made mention of these matters.

Time went on, and Alexandros took Helene to wife: Oinone took his conduct exceedingly ill, and returned to Kebren, the author of her days: then, when the war came on, Alexandros was badly wounded by an arrow from the bow of Philoktetes. He then remembered Oinone's words, how he could be cured by her alone, and he sent a messenger to her to ask her to hasten to him and heal him, and to forget all the past, on the ground that it had all happened through the will of the gods. She returned him a haughty answer, telling him he had better go to Helene and ask her; but all the same she started off as fast as she might to the place where she had been told he was lying sick. However, the messenger reached Alexandros first, and told him Oinone's reply, and upon this he gave up all hope and breathed his last: and Oinone, when she arrived and found him lying on the ground already dead, raised a great cry and, after long and bitter mourning, put an end to herself. (Chapter IV)

Her story is also told by Ovid in his Heroides (written c. 4-8 CE) but here it is framed as a letter from Oenone to Paris. Ovid's version also includes elements which are not found in Parthenius or the earlier writers. Ovid's piece begins with Oenone insulting Paris' manhood by asking whether he will be allowed to read her letter or whether his new wife will forbid it and he will not have courage or authority enough to defy her.

The letter continues by reminding him of his vow of eternal love and how happy they once were together, noting how she lowered herself – as the daughter of a god – to marry with someone who was not only a mortal but, as far as she knew, only a shepherd's son and not even of noble birth. She reminds him of their time together and how he once carved their names into the trunk of a tree after promising he would never leave her and, further, how he swore that her father could cause the river Xanthius to flow backwards if he should break that promise.

Ovid then has Oenone recollect how she begged Paris not to go to Sparta, crying as she watched him leave, and tells him that Menelaus is justified in launching the war to bring his wife back and how, since Helen was unfaithful to Menelaus, she will also be to Paris. She tells him that many have desired her, before and after she met Paris, but she has always been faithful to him. Oenone's letter ends with her plea for him to remember their love and happier days and return to her.

The story is also told by the British poet and scholar Robert Laurence Binyon (l. 1869-1943 CE) famous for his poem For the Fallen published in 1914 CE and regularly recited at Remembrance Day in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the UK. In 1906 CE, Binyon published his work, Paris and Oenone: A Tragedy in One Act, based on the work of Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica, chapter X. 259-489 (4th century CE).

Binyon's play begins with Oenone weeping over Paris' betrayal of her for Helen. Paris then enters the scene, mortally wounded, and reminds her of her promise to heal him if ever he were hurt. Oenone refuses, still stung by his desertion, and Paris limps away to die. Oenone then repents and goes after him but finds Helen instead who is also trying to find Paris and help him. Oenone tells Helen she can save Paris with her magic herbs and skills taught her by Apollo but, as she does, she and Helen learn Paris has died as his funeral pyre is lighted behind them. Oenone, consumed by grief for her one true love, then runs and leaps into the flames while Helen watches helplessly.

Conclusion

In every version of the story, Oenone is represented as the dutiful and loving wife who is deserted by her one true love and takes her own life in response. Bell writes:

Oenone could quite easily be called the epitome of the abandoned wife, but one unwilling to accept her fate without resorting to a series of actions to recover her lost love. Her first attempt was reasoning, but that failed. Then she tried a thwarting tactic by providing her son as a weapon to end the war quickly. When that didn't work, she tried to discredit her rival. Finally, she allowed the death of her self-destructive ex-husband, but repented and, in a final desperate action, tried to save him. After that, there was nothing left but her own destruction. (331)

Oenone continued - and continues - to be remembered this way as a cautionary tale to women who devote themselves to men who do not deserve their love. In the present day, she is also referenced in grief therapy in pointing out the danger of refusing to let go of what has been lost.