Old Dongola (aka Dungulah or Dunkula), located in modern Sudan, was the capital of the ancient Nubian kingdom of Dongola (aka Makuria or Makurra) which flourished from the 6th to 14th century CE. A Christian kingdom for at least 750 years and then Muslim after incursions by the Mamluks of Egypt in the early 14th century CE, Dongola prospered thanks to agriculture and trade relations with the Byzantine Empire via Egypt and African kingdoms to the south and east. Today, Old Dongola's ruined stone churches and royal palace leave a tantalising record of the wealth this mysterious desert kingdom once enjoyed. It is not to be confused with the modern Sudanese city of Dongola, which is located some 160 km (100 miles) to the northwest.

Historical Overview

The area around Dongola was inhabited from at least 6000 BCE, with pottery finds being radiocarbon dated to c. 5000 BCE. These small agricultural communities and groups of pastoralists probably traded with ancient Egypt to the north during the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) if not before. The settlement of Old Dongola grew from the 6th century CE and was located on the River Nile bend between the third and fourth cataract in what is today northern Sudan. The kingdom prospered thanks to the use of the water wheel (saqia), which irrigated land previously unsuitable for agriculture. Crops grown in the region included wheat, barley, millet, dates, and vines. Animals kept included cattle, sheep, chickens, and donkeys.

Adoption of Christianity

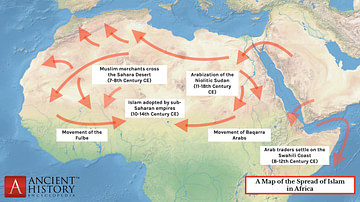

The Kingdom of Dongola adopted Christianity (orthodox Melkite) following a mission originally sent by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) which arrived between 540 and 543 CE after having travelled down from then Christian Egypt. However, there had already been Christian missionaries in the kingdom before this and the precise date of the religion's official adoption is not known. Tombs have also indicated that some pre-Christian practices still continued well into the Christian era of Nubia. Around a century later, the kingdom adopted the Monophysite doctrine of Christianity following influence from the Christian Kingdom of Axum (in modern Ethiopia, 3rd-6th century CE) and another Byzantine mission, this time led by one Bishop Longinos who trained local clergy. In a further connection, the Patriarch of Alexandria would appoint the bishops in the Kingdom of Dongola right through the medieval period. The religion was further spread throughout the kingdom via the establishment of churches in towns and rural monasteries.

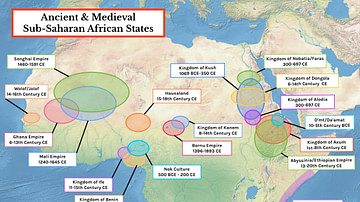

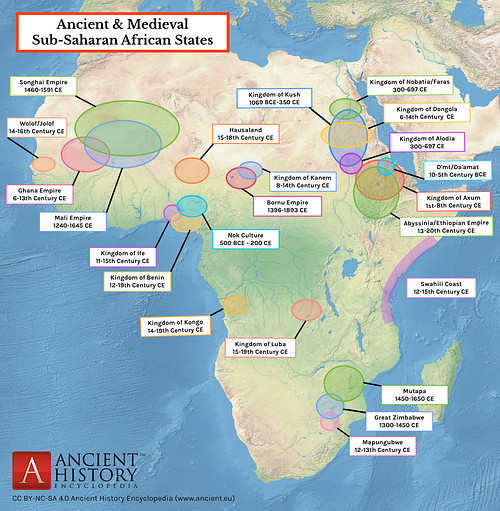

The 7th century CE saw the Kingdom of Dongola absorb the smaller neighbouring Christian kingdoms of Faras (aka Nobadia), located to the north, and perhaps, too, Alodia in the south, forming a unified state led by King Merkuiros of Dongola (r. from 697 CE), which remained the capital. The unification was likely a response to the increased threat from Muslim North African states, especially Egypt, although Nubian warriors, armed with javelin, sword, and bow, were able to hold their own and maintain the kingdom's independence. However, a large Muslim raid in 651 CE, which included a 5,000-strong Muslim force, had attacked the capital Old Dongola with catapults. As a result of this siege, a truce was declared and a treaty was signed between Dongola and Egypt c. 652 CE, known as the baqt. In return for an annual tribute of 360 slaves, the Christians would receive grain, cloth, and wine. All Muslims were to be given protection as they passed through the kingdom, any person was to be allowed to worship in a mosque at Old Dongola, and any escaping slaves were to be sent right back northwards. In return, Dongola was to be left to its own devices. Although some minor conflicts did break out, the treaty was largely respected for the following six centuries.

Trade

Peace and the unity of the Nubian kingdoms brought prosperity. Trade networks connected Dongola to neighbouring states, especially Egypt as evidenced by a large number of Egyptian amphorae found at Old Dongola and other Nubian sites. Ivory was exported to the Byzantine Empire while gold went to Ethiopia. In the other direction, ceramics and glassware were imported in great quantities from Egypt. Byzantine influence was not only seen in religion and trade relations but also general culture, with the well-off residents of Dongola adopting Byzantine clothing and women wearing long colourful robes decorated with intricate embroidery. The political administration was similarly modelled on Byzantine ideas with an eparch governing provinces. Yet another Byzantine influence was the use of the Greek and Coptic languages in the kingdom, as well as (from the 9th century CE) the indigenous Old Nubian. Few details of everyday life and culture are known beyond those mentioned above, although, Dongolan farmers were tenants as the king owned the lot and taxes were payable to him depending on land occupied.

The Mamluk Conquest

The stability Dongola had long enjoyed was rudely shattered by the Mamluks of Egypt (1250-1517 CE) who attacked the kingdom in 1276 CE. Fortunately, Dongola remained just on the edge of the Mamluk Empire and seems not to have been considered rich enough to bother too much about. In 1315 CE, however, the Mamluks again showed an interest in the region and, returning in force, installed a puppet ruler. The cathedral and palace of Old Dongola were converted into mosques in 1317 CE. Both the Muslim Mamluk ruler and the Kingdom of Dongola were then attacked by the nomadic Juhayna Arabs who swept into Sudan from northern Egypt at some time in the 14th century CE. Certainly, by 1365 CE, the kingdom had moved its capital from Dongola to Daw (of uncertain location but possibly Jebel Adda to the north).

The Kingdom of Dongola, not for the first time in its history, then fades into historical obscurity for a few centuries and only receives the briefest hints of its existence from European missionaries visiting Ethiopia who heard of a mysterious Christian kingdom somewhere in the desert to the west. In the 17th century CE, the Darb el-Arba'in camel caravan route ran through Old Dongola and Nubian rulers collected duties at Argo near Kerma in northern Sudan. The presence of large stone Islamic tombs, known as qubbas and shaped like massive beehives, are a testimony to the region's continued ability to generate wealth in this period. However, by the 18th century CE, the caravan route had shifted elsewhere and Dongola was definitively abandoned, its ruins left to the desert sands. Polish archaeologists have been excavating the dunes of Old Dongola since 1964 CE.

Architecture

In the 7th century CE, Old Dongola boasted two large Christian churches built in a Nubian version of the Byzantine basilica. The first, known today as the Church of the Granite Columns, had a cross in a square floor plan with a wide nave and an aisle on either side. The granite columns, which give the church its name, today number 16 in total, reach a height of 5.2 m (17 ft) and were topped with well-carved volute capitals. The walls were built of baked brick and strengthened by occasional horizontal wooden beams and cross-ties at the corners. The roof was flat and made of wood with horizontal supporting rafters. Where such long and heavy wooden beams came from is unknown. The second church, known as the Church of the Mausoleum, has a symmetrical cross floor plan with a large central square space. Giving the church its name is a rectangular mausoleum attached to the rear of the building.

Besides the remains of two more churches, the city also boasted a city wall, large houses and wide streets. A baked red-brick two-storey palace, once with domes, dates to c. 1002 CE, while most ordinary housing was constructed using unbaked mud bricks. These estates spread over an area of some 35 hectares or 350,000 square metres at Old Dongola. Housing may have used simple materials but many that have been excavated, which date to the 9th century CE, have their own bathroom, water supply, and heating system.

Arts

The interiors of buildings and especially churches in the kingdom were painted with large frescoes, those in the cathedral of Faras are amongst the finest and show scenes from the Bible and portraits of local dignitaries. Potters in the Kingdom of Dongola produced their own fine wares, superior to those of contemporary Egypt. In the 9th century CE, ceramics were brightly coloured and further decorated with scenes of animals and floral patterns. Weaving was another important industry. Cloth made from wool and camel hair had brightly coloured stripes or check designs and were highly sought after by neighbouring kingdoms. Iron tools, palm-fibre baskets, and leather goods were also manufactured in great quantities, and there is still today a strong local tradition for making such everyday items.