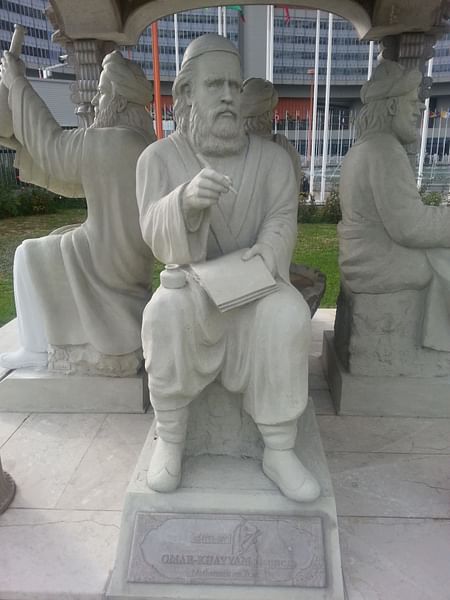

Omar Khayyam (also given as Umar Khayyam, l. 1048-1131 CE) was a Persian polymath, astronomer, mathematician, and philosopher but is best known in the West as a poet, the author of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. His famous work has been embraced by the West since it was translated in the 19th century CE.

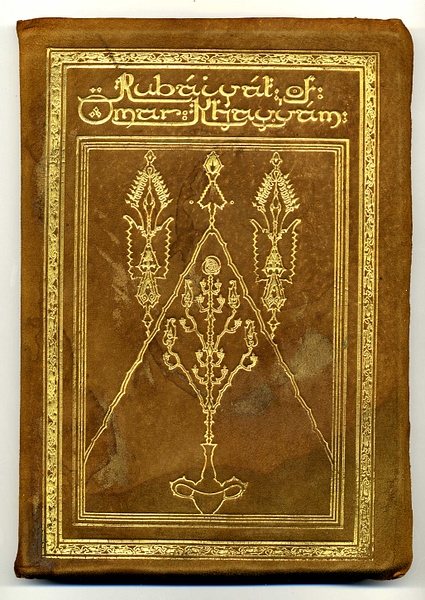

The Rubaiyat was translated and published in 1859 by the English poet Edward Fitzgerald (l. 1809-1883) and would become one of the most popular, oft-quoted, and frequently anthologized works in the English language. Khayyam's name became so well-known among English speakers that organizations were founded in his honor which encouraged interest in other Persian poets and their work.

In the East, however, Khayyam is known primarily as a scientist, particularly as an astronomer and mathematician who contributed to the Jalali Calendar (a solar chart which corrected the Islamic Calendar) and as a philosopher whose works prefigured the existentialist and humanist movements. Until fairly recently, Khayyam was not recognized primarily as a poet in the East – certainly not of the stature of Rumi or Hafez Shiraz – and modern-day scholars have questioned whether Khayyam even wrote the poems that make up his famous Rubaiyat because, to some, the poetry represents a very different worldview from the philosophical works.

This seeming contradiction, however, can be explained by Khayyam's use of poetry to express his personal feelings about life which he did not want to frame as philosophical discourse. For Khayyam, though a devout Muslim, the painful realities of human existence could not be explained by the Quranic insistence on a loving God who had created the world according to a divine plan. His beliefs brought him into conflict with devout Muslim jurists and so he tempered his public discourse and probably wrote his poems for himself.

These poems, consciously or not, draw on the pre-Islamic Persian belief system of Zorvanism in which Infinite Time is the creator and controller of all things, human life is predestined (and brief), and there is nothing one can finally do to alter one's destiny. The only rational course open to a human being, therefore, was to enjoy life as best as one could – especially through drink and good company – and to set aside worries which only served to waste the little time one had been given on earth.

Early Life & Influences

Khayyam was born in Nishapur (modern-day northeastern Iran) where he would spend most of his life. His family is thought to have been (or were descended from) tentmakers, which was a respectable and lucrative profession. His parents were certainly of the upper class as he was sent to study with the greatest teachers of the city who only accepted students from prominent families. One of these teachers was the mathematician Bahmanyar (d. 1067 CE), a former student of the great polymath and physician Avicenna (l. 980-1037 CE) and a former Zoroastrian who had converted to Islam. It is possible that Khayyam learned Zoroastrian/Zorvanist precepts from him but it has also been suggested that Khayyam's father was a former Zoroastrian, who had also converted to Islam, and if so, the young scholar would have been acquainted with the ancient faith from an early age. Khayyam's references to himself as a “student of Avicenna” are allusions to his time with Bahmanyar from whom he learned Avicenna's scientific method of observation and inquiry.

His earliest teacher appears to have been Imam Mowaffak of Nishapur, a renowned scholar and, according to Edward Fitzgerald (in his preface to the Rubaiyat), it was under Mowaffak's tutelage that he met Nizam al-Mulk (d. 1092 CE), the future vizier of Baghdad. Fitzgerald relates a passage from al-Mulk's Testament in which the vizier recounts his days in Nishapur and his two closest friends and classmates, Omar Khayyam and Hasan Ben Sabbah. One day, Ben Sabbah remarked to his friends how it was well known that those who studied under Mowaffak attained great success and how it was quite likely that at least one of them would. He then proposed that whichever of them should meet with the greatest success, that one would share it equally with the others.

Mathematics, Astronomy, & Philosophy

In mathematics, Khayyam wrote treatises which, according to the interpretation of some scholars, show that he understood and employed the concept of the binomial theorem and that he also was able to revise and improve upon Euclid's work with apparent ease. He also contributed to the understanding and usage of algebra and geometry, working in what he called pure arithmetic, which enabled his astronomical pursuits. Under the patronage of Nizam al-Mulk, Khayyam traveled to Isfahan in 1074 CE to a newly established observatory where he was instrumental in perfecting the Jalali Calendar, a solar calendar considered far more accurate than the Gregorian Calendar, still in use today in the region of Greater Iran.

In his philosophical works, he argued for God as a Necessary Being (very like the Unmoved Mover of Aristotle) from whom all else proceeds and, accordingly, human free will is subject to divine will. Since one has no control over when one will be born, to what station in life, in what region, or under what circumstance, one's life is necessarily begun beyond one's ability to control and proceeds from that point on with life determined by God's will. If this is so, however, then God is also responsible for the evil in the world; a serious contradiction of definition given that God, in order to be worthy of worship, must be all-good. Khayyam sidesteps this dilemma by characterizing evil as an absence of good. Evil appears when God's directives are ignored, when one pushes back against what is divinely determined, or is simply one's interpretation of a natural event.

In this view, what humans define as “evil acts” are a contradiction of God's plan, not a part of it, whereas the aftermath of such acts can still be part of the Divine Plan in so far as a person can recognize and respond correctly. Not everything, it could then be argued, is “determined” since one's response would be an act of one's own will but, at the same time, that exercise of free will is determined by one's past up to that moment.

Khayyam advances the theory (later articulated as the Hierarchy of Needs by psychologist Abraham Maslow, l. 1908-1970) that one cannot pursue self-improvement or higher goals until the basic necessities of life are met. Khayyam writes:

God created the human species such that it is not possible for it to survive and reach perfection unless it is through reciprocity, assistance, and help. Until food, clothes, and a home, that are the essentials of life, are not prepared, the possibility of the attainment of perfection does not exist. (Aminrazavi & Van Brummelen, 8)

This concept is also an echo of Aristotle who, in his Nichomachean Ethics, states that the purpose of human life is happiness but, to attain this state, one must first have provided for one's physical needs (Book I, 1098b.12-32; Book III, 112b.12-30). Khayyam's concept of virtue, defined as acting in accordance with the highest precepts of the self, are also Aristotelian while his argument concerning essence – as in what it means to be a human being – is Platonic. In his use of these philosophers, as well as others and of religious concepts, Khayyam adds his own personal touch which is largely informed by Zorvanism.

Zorvanism & The Rubaiyat

Zorvanism was a sect (sometimes referred to as a heresy) of the Persian religion of Zoroastrianism which seems to have first emerged during the latter part of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) and was fully developed by the time of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE). Zoroastrianism held that there was one supreme, all-good and uncreated deity – Ahura Mazda (later given as Ormuzd) – from whom all else was created and that human beings had free will to choose to follow the precepts of Ahura Mazda or reject him and side with his arch-rival Angra Mainyu (also known as Ahriman), the embodiment of evil. The problem with this religious construct was that if Ahura Mazda was all-good, where had Ahriman and evil come from?

Zorvanism attempted to solve the contradiction by elevating Zorvan, a minor god of Time from Early Iranian Religion, to the position of Supreme Deity. The androgynous Zorvan, representing Infinite Time, wishes for a son and prays to himself for a good result in impregnating himself. Nothing happens, however, and he experiences a moment of doubt – in which Ahriman is conceived – but then banishes this doubt and regains faith in himself – engendering Ahura Mazda/Ormuzd. Zorvan proclaims he will give sovereignty of the world to whichever twin is born first and Ahriman, hearing this, cuts his way out of the womb and assumes mastery. Zorvan corrects this by decreeing that Ahriman will only have sovereignty for 9,000 years, after which Ahura Mazda/Ormuzd will reign. Ahura Mazda, then, is the creator of the world but the “evil” one experiences in life comes from Ahriman.

The Moving Finger writes and, having writ,

Moves on; nor all your piety nor wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a line,

Nor all your tears wash out a word of it.

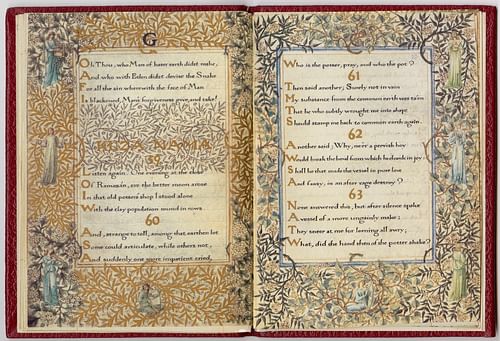

One's daily life is dictated by Time – the “moving finger” – whose writ propels one through life, whether one wants to move on or remain where one is, and there is nothing one can do to change that. Therefore, Khayyam proposes throughout the work, the best course is to eat, drink, and be as merry as one can be before one is snatched unexpectedly by death. The brevity of life, and how one should best respond, is central to the work from beginning to end. Fitzgerald's translation makes a point of forming the various poems into a narrative beginning with the opening of a tavern in the morning and moving on to one of the patrons musing on the meaning of life, injustice, evil, pleasure, and death, before closing with the moonrise at night and remembrance as the only hope for one's immortality.

Stanza 1 awakens the reader to the morning of the narrative, stanza 2 encourages one to fill one's cup “before life's liquor in its cup be dry” and stanza 3 has the patrons gathering outside the tavern door, demanding it be open for, “You know how little while we have to stay/And once departed may return no more”, while the last stanzas, 74 and 75, depict the day's end, the moon rising over the tavern's garden in the night sky, and how, on some future date unknown, the beloved of the speaker will look to the garden where they have enjoyed themselves and find him gone. The poem ends with the request that the beloved remember the speaker by turning down an empty glass at the place where they used to spend time together as envisioned in the famous stanza 11:

A book of verses underneath the bough

A jug of wine, a loaf of bread, and thou

Beside me, singing in the wilderness –

Ah, wilderness were paradise enow.

The most reasonable response to the tyranny of time is defiance in the form of sensual enjoyment, as Khayyam points out repeatedly, as, to cite just two examples, in the first lines of stanza 23, “Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend/Before we too into the dust descend” and in stanza 37:

Ah, fill the cup; what boots it to repeat

How time is slipping underneath our feet

Unborn tomorrow and dead yesterday

Why fret about them if today be sweet.

Although some scholars have claimed that Khayyam's use of wine and drunkenness is in keeping with the Sufi tradition (expressed in the works of Rumi and Hafez Shiraz), this is untenable in that Sufis of Khayyam's time rejected his work and Khayyam shows no affinity for Sufism in any of his writings. The Sufis regarded him as an overly scientific atheist based on his treatises and discourses. In his philosophical work, Khayyam addresses the nature of life and its various disappointments from an objective, scientific standpoint and emphasizes the importance of an educated, rational response to human existence. One suffers – or seems to suffer – because of one's interpretation of external events which are predetermined; this is hardly in keeping with the Sufi philosophy. In the Rubaiyat, on the other hand, he laments the brevity of life, the loss of friends, and how Time robs one of youth and pleasure; none of which fits the Sufi vision either.

Authorship & Translation

Khayyam's pessimism and embrace of a life of enlightened hedonism has encouraged some scholars to suggest the author of the Rubaiyat cannot be the same as the Omar Khayyam who wrote the philosophical discourses. The Rubaiyat, after all, rejects intellectual pursuits in favor of wine, good company, and song. Stanza 27 disparages academic pursuits completely:

Myself when young did eagerly frequent

Doctor and Saint and heard great argument

About it and about, but evermore

Came out by the same door as in I went.

This criticism, however, ignores the fact that the speaker of the poem is a fictional character, who may or may not be speaking for the author. Even if he is, the philosopher-poet, in any age or culture, is not always able to completely balance the two sides equally all the time; what the philosopher explains away, the poet rages against. Far from suggesting that the Rubaiyat cannot be written by the same author as the discourses or mathematical treatises, Khayyam's verse acts as a kind of mirror to his prose, reflecting precisely the opposite response to life.

No one contests that Khayyam wrote poetry, only that he may not have written the pieces which comprise his famous Rubaiyat. Khayyam as a poet is attested by the Persian historian and scholar Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani (l. 1125-1201 CE) and the Persian polymath Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (l. 1150-1210 CE) who quotes stanza 62 of the Rubaiyat completely. Even so, some scholars continue to keep alive the criticism that the book could be the work of another poet.

Edward Fitzgerald…did not set out to translate the quatrains of Omar Khayyam. In a letter he remarks `God Forbid' that he should be thought to be translating. He was, in fact, working in the now almost forgotten tradition of the Imitation. Since he was possessed of the genius of a poet, his imitation is one of the most successful poems in the English language…Of it, Fitzgerald used the coinage `transmogrification'. (Lewisohn, xiii)

Even so, Fitzgerald had learned Persian from his colleague and friend Edward Byles Cowell (l. 1826-1903) and so he was working from Khayyam in the original language. Fitzgerald's The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam is, therefore, as much the work of the Victorian English poet as the medieval Persian. This “collaboration” has been recognized as one of the most successful in literary history as The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam would attract worldwide attention by the beginning of the 20th century, introduce a Western audience to Persian literature, influence countless artists in different mediums, revive interest in Khayyam scholarship in the East, and remain a bestseller for the past 100 years. Modern audiences respond to Khayyam's work as warmly as the Victorians for the same reason: the beauty of a poetic vision offering an alternative to despair in navigating a life characterized by loss and defined by the inevitability of death.