Orisha (also given as Orisa and Orishas) are supernatural entities usually referred to as deities in the Yoruba religion of West Africa, though they are actually emanations or avatars of the supreme being Olodumare. Their number is usually given as 400 + 1 as a kind of shorthand for "without number" or innumerable.

Belief in the Orishas is thought to have developed between 500-300 BCE but is most likely much older, as this dating is supported by archaeological evidence and there are many West African sites still unexcavated. According to the Yoruba belief, Olodumare is too immense for the human mind to grasp and so released different aspects of itself, each of which received a certain sphere of influence randomly. Olodumare threw the powers of dominion into the air, and whichever Orisha caught one was responsible for that sphere of influence.

The Orishas traveled to the Americas and the Caribbean via the Transatlantic Slave Trade, when many of the Yoruba were enslaved, and there they became syncretized with the Christian saints of Catholicism. The Yoruba were able to continue practicing their religion by nominally becoming Catholic as the saints served the same purpose in Catholicism as the Orishas did in their native faith, as intermediaries between a believer and the supreme deity.

In the modern day, people invoke the Orishas in personal or communal rituals for spiritual strength, enlightenment, or assistance in daily challenges. Although there are many Orishas, seven are understood as most powerful and have become the most popular among modern-day adherents. Orisha worship today is practiced by people around the world in a number of forms including the systems of Santeria, Candomblé, and Vodun, as well as nominal Catholics and those who identify as Neo-Pagan, Wiccan, or New Age practitioners.

Yoruba Religion

The beliefs of the Yoruba faith were passed down orally for generations until committed to writing and so there are a number of different versions of the same stories. In some, the supreme being is referenced as Olodumare, in others, it is Olodumare-Oloorun, in still others, Olofin, but all refer to the same entity – neither male nor female – who both created and is the universe. A number of modern-day works on the Yoruba faith claim that Olodumare dwells high in the heavens remote from the concerns of those on earth and cannot hear people’s prayers, but this does not seem to be supported by the stories in which the entity is both aware of and engaged in the struggles of both Orishas and mortals. Scholar Alex Cuoco comments:

Olodumare-Oloorun is the Supreme, Almighty God of the Yoruba and not an Orisha. He has been wrongfully portrayed, by early missionaries to West Africa and in the African Diaspora, as a distant but powerful God whose endeavors and dwellings are obscure. However, contrary to the missionaries’ and the Diaspora’s view, Olodumare-Oloorun is a powerful God that is always present in everything, even though He is above the Orishas and all people on earth. (2)

Cuoco’s use of the male pronoun is for convenience as Olodumare is All Things and so both male and female. In Yoruba cosmology, Olodumare sits at the top of the hierarchy, and everything else descends down from him:

- Olodumare

- Orisha

- Human Beings

- Human Ancestors

- Plants and Animals

On the same level as the Orisha are the Ajogun, who are difficult to define but are often associated with the Western concept of a demon. An Ajogun is a supernatural being who causes trouble, encourages misunderstandings, brings illness, and causes accidents. They are not demons, however, because according to Yoruba belief, all things in creation – natural and supernatural – are possessed of the aspects of positivity (ire) and negativity (ibi) and so nothing can be understood as wholly good or completely evil. It is possible the Ajogun are Orisha tricksters, but whatever they are, they cannot be considered 'evil' or 'demonic' in a Christian sense.

Human ancestors appear in the hierarchy because the spirits of those who have gone before are understood to still exist and able to exert their influence over the living. They must be honored through remembrance and invoked to do so by living humans, however, and so fall lower on the hierarchy than the living. Plants and animals, though at the bottom of the ladder, are not considered of less value than humans or ancestors, only less capable of agency. Plants and animals are understood as possessing the same divine spark as human beings.

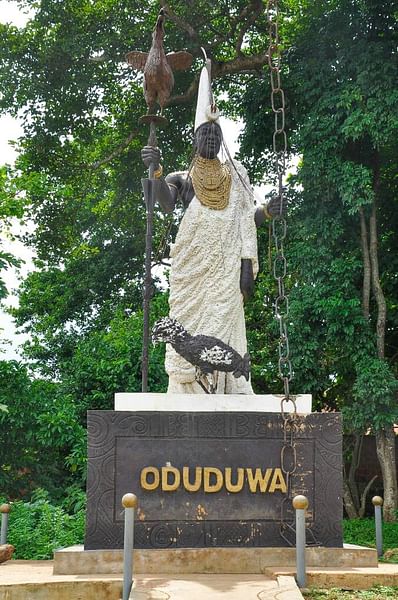

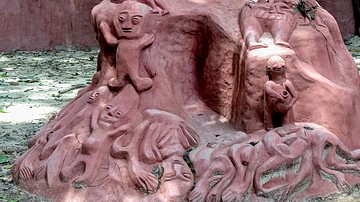

The Yoruba creation story, like many others, has different versions. In one, far back at the beginning of time, Olodumare created the Orishas and spread powers between them randomly. The Orishas then huddled by the great baobab tree that provided them with everything they needed and refused to use their powers for creation, preferring to satisfy their own needs. Olodumare then took care of the act of creation through the Orisha (or god) Oduduwa, who made the Yoruba people and established life at the city of Ife (also Ile-Ife) as well as the concept of cultural identity and kingship. Whether the Orishas then decided to participate in creation is not addressed.

Their participation in creation is given in another version, however, where the Orisha Obatala separates the land from the waters and Olodumare then sends down 17 Orishas to complete the work. 16 Orishas are male and the 17th, Oshun, is not only female but the youngest among them. The males ignore her efforts and suggestions and wind up failing in their task. They are forced to return to Olodumare and admit their failure and are asked what happened to the 17th who was sent with them. The male Orishas confess they ignored her because she was a woman and much younger and are told only she can complete the work. The Orishas return to earth and apologize to Oshun who finishes creation with the gifts of beauty, fertility, love, and sweetness, instilling the need for these things in all people everywhere who had been given life through the breath of Olodumare.

All humans, therefore, are connected to each other – no matter their appearance, religion, or location – because all owe their existence to the same divine breath that animates them, and all humans are related to other living things for the same reason. The animating force is known as Ashe (or Ase) and is essentially life itself as it is in constant motion and transformation. Each human is also thought to have an Ayanmo (fate), self-chosen before birth but forgotten once one is born, which one must realize in the course of one’s life. If one is unable to do so, for whatever reason, one is reincarnated and tries again in the next life.

The Orishas exist to help humans reach their goal of self-actualization, but these entities are not perfect themselves and sometimes get in peoples’ way, often without meaning to, because they each have their own individual personality and flaws just as humans do. Orishas, like mortals, are supposed to devote themselves to developing a strong character that pursues what is good and shuns what is evil, but neither people nor Orishas are capable of doing so all the time, and personal weakness, desire, pride, spite, and arrogance often come between what the Orishas know they should do and what they want to do.

Olodumare & the Orishas

The best examples of this are the stories in which the Orishas rebel against Olodumare in the belief that the supreme deity is too old to manage the maintenance of the world and they could do much better. In one tale, the Orishas gather to discuss how they can rid themselves of Olodumare and decide to scare him to death by inviting him to one of their huts and then releasing mice, which Olodumare was afraid of, into the room at dinner. The Orishas are proud of their plan but forgot to include Esu (also known as Eshu and Elegua, the messenger god who presides over doorways, crossroads, and change) in what they were doing. Esu knew their plan, however, because he was present in the doorway when they formed it but did not warn Olodumare of their intentions.

On the given day, Olodumare came to the Orisha hut where the mice were hidden, happily expecting to share a meal with others but, as soon as the threshold was crossed, the door slammed shut, and hundreds of mice were released scampering across the floor. Olodumare was terrified and ran from the mice, but Esu appeared, calmed the deity, and quickly ate up every mouse. Olodumare demanded to know who had done this, and Esu pointed out the guilty who were swiftly punished. Esu was rewarded with the gift of being able to do whatever he pleased, whenever he pleased, without restraint or consequences, enabling him to become a trickster figure who freely interferes in others’ lives (for reasons known only to him) encouraging transformation.

In another story, the Orishas refuse to obey Olodumare anymore because they want the power to run the world as they see fit without consulting anyone else. Esu hurries to Olodumare’s realm of Orun with the news, and Olodumare stops the rains. The earth begins to die as crops fail and lakes and rivers dry up, and the Orishas wail their repentance, but Olodumare does not hear them. Oshun turns herself into a peacock and flies to Orun but, passing too close to the sun, loses most of her feathers and, because the journey was so long, arrives exhausted and ill but still delivers the message of the Orishas’ contrition. Olodumare releases the rains, heals Oshun, and declares her the only Orisha always welcome to bring messages to Orun.

The Seven Orishas

The Orishas are not always causing trouble for Olodumare, however, and most of the time are attentive to their responsibilities. It is understandable how one would conclude that Olodumare is too far away from human affairs for mortals to make contact, but at the same time, it should be recognized that each Orisha is an emanation of Olodumare and so the supreme being is aware of every prayer of thanks or supplication made to any Orisha.

As noted, their number is most often given as 400 + 1 to suggest how limitless they are. The understanding is that, even if one thought one knew every Orisha and could name them all, there would always be one more one had missed. Even so, not all the multitude of Orishas appear in the stories – frequently only 20 or 30 at most do so – but there are seven that appear often who have become the most popular and are referred to as gods and goddesses:

- Esu – messenger god who presides over crossroads, doorways, and transformation

- Ogun – (also Ogoun) god of metallurgy, strength, transformation, and healing

- Obatala – sky god of creation, protector of the weak and disabled, champion of purity

- Yemaya – Mother of All Water, the Divine Earth Mother, protector of women

- Oshun – goddess of sweet water, fertility, love; second wife of Shango

- Shango – god of lightning and thunder, fire, virility, war, foundations

- Oya – goddess of transformation and rebirth, guardian of the dead; third wife of Shango

These are all only the most basic descriptions of the dominions of the Seven Orishas. Oya is also goddess of the Niger River as Oshun is of the Osun River, and both are associated with protection and guidance. All can be said to be transformative figures to greater or lesser degrees, and their responsibilities are far-ranging. Esu, for example, as a deity of crossroads, acts as a psychopomp – a guide for the souls of the dead – bringing them to the afterlife and comforting them while, at the same time, he may have had a hand in the circumstances that led to their death. Ogun is able to destroy as easily as heal, as is Oshun when she is displeased, and Shango can lash out in anger with thunder and lightning as often as he does in justice.

Orishas & the Catholic Saints

The Orishas are never represented as perfect beings, and there are a number of stories of them behaving badly, but they are depicted as trying their best to do what is expected of them in very human terms. Oshun can be spiteful, Shango impatient, Esu deceitful, Yemaya wrathful, and so on. They can be counted on, however, to deliver the messages of mortals to Olodumare and so they came to be associated with the saints of Catholicism when the Yoruba people were brought as slaves to the so-called New World.

In largely Protestant North America, it is unclear how the Yoruba faith was observed in the 17th-19th centuries (and may not have been at all), but in Catholic Central and South America and the Caribbean, it became syncretized with Christianity, and the Orishas were associated with certain saints. Like the stories told by the Yoruba in West Africa, different Orishas were linked to different saints in different regions, and it is not possible to definitively say which Orisha came to be identified with which saint. Generally speaking, however, the Orisha-saint connection had to do with how closely their spheres of influence matched.

Esu, for example, was associated with Saint Anthony of Padua, patron saint of lost items, people, and paths in life, because of his role as guardian of crossroads and guide in transitions. Ogun was linked with Saint Peter because of his association with strength as Peter was known as the 'rock' upon which Jesus Christ would build his church. Yemaya came to be linked with the Virgin Mary as Our Lady of Regla in Cuba while Oshun was associated with the same figure as Our Lady of Mercy. Shango was linked with Saint Barbara who is invoked for help in thunderstorms but is also the patron saint of artillerymen and so linked to war. The other Orishas followed this same pattern with many of the females associated with the Virgin Mary under her different epithets in various regions.

Conclusion

Orishas, like the saints, were relatable because they were fallible. St. Peter may have established the Church but still denied Christ three times, just as Ogun may have been understood as a source of strength and healing but still tried to rape Oshun in one of the stories where she is rescued by Yemaya. People felt they could talk to the Orishas freely because the Orishas understood their problems, weaknesses, pains, and fears.

In another story from the Yoruba religion, after the world was created and populated, every human was equal, and no one wanted for anything. As time went on, however, people began to complain about this situation noting how, if everyone had everything they needed, and if everyone was equal, no one could be any different from their neighbor and they had no goals to strive for. They complained loudly to Olodumare, and their cries were delivered by Esu who, as usual, acted as an intermediary.

Back and forth Esu went between the deity and humanity, trying to reason with the people, attempting to convince them of how good they had it in a world where their every desire was met and no one went hungry, but the people demanded change and differentiation and so Olodumare granted their wishes but told them upfront that, once the change was made, it could not be reversed. Afterward, those with lighter skin complained they were not darker, and those with darker skin wanted to be lighter, the poor robbed the rich, and the rich enacted laws against the poor, resources were gathered and defended by one people against another, and there was want and starvation, war and privation. The people were sorry for having questioned the plan of the supreme deity but understood they had received exactly what they had asked for and would have to live with it. They were given aid, however, through the efforts of the Orishas.

The Orishas, after all, had questioned the wisdom and justice of Olodumare and repented of it more than once and so were sympathetic to the human condition. In the Orishas’ case, Olodumare had allowed life to continue as it had before, but the supreme deity had made clear to humanity that, once they chose inequality as the basis of their existence, they could not go back to their former lives.

The best one could do, then, was pray to Olodumare through the Orishas for the strength to endure and try to prevail in a world where one does not always get what one wants and, even when one does, it can completely fail to live up to expectations. In the present day, the Orishas continue to be invoked by adherents for these same reasons and, according to the belief, are still just as alert and responsive to human need as they have been since people first received the breath of life at the beginning of time.