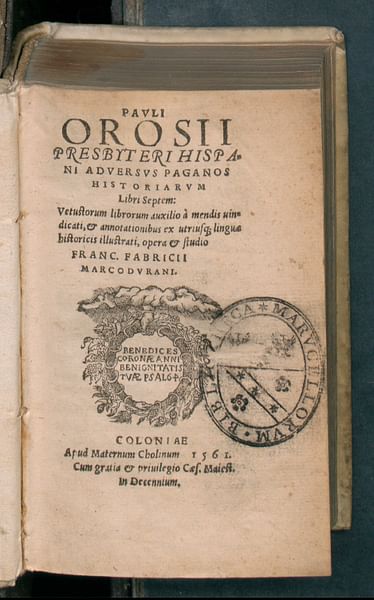

Paulus Orosius (usually given as Orosius, 5th century CE) was a Christian theologian and historian who was also a friend and protege of St. Augustine of Hippo (l. 354-430 CE). He is best known for his work Seven Books of History Against the Pagans in which he argued that the 410 CE sack of Rome by Alaric I, King of the Goths (r. 394-410 CE) had nothing to do with the Roman adoption of Christianity, a claim popularly supported among the pagans of the day. He was encouraged to undertake the work by Augustine whose book City of God was inspired by the same event. Tracing the history of the world from creation to his own time, from a Christian perspective, Orosius' work was immensely popular with followers of the new religion and became a standard history referenced by later writers. Following the publication of his book, he disappears from the historical record.

Life & Career

Little is known of Orosius' early life. He was probably born in Portugal to an upper-class family in c. 380 CE and entered the priesthood at some point in his early years, probably before the age of 20. In 414 CE he was forced to leave his home in Hispania quickly (for unknown reasons) and booked passage on a ship to Hippo in North Africa to meet Saint Augustine. He seems to have made a good impression on the older cleric because, the next year, Augustine sent him to Jerusalem to debate with the heretic Pelagius, author of the Pelagian Heresy, which claimed that man was capable of individual salvation without the church's intercession.

In Jerusalem, Orosius conferred with Saint Jerome and John, Bishop of Jerusalem and faced Pelagius at a synod called to discuss the heresy. The outcome was inconclusive but, in the official report sent to Rome, Orosius' own orthodoxy was questioned. This charge prompted him to write his defense in the book Liber Apologeticus contra Pelagianos (Defense against Pelagius) maintaining his orthodoxy while condemning Pelagius.

Orosius left Palestine at some point in early 416 CE, having been given the relics of the first Christian martyr Saint Stephen (from the biblical Book of Acts 6 & 7) to bring back to his home in Portugal. He stopped first in Hippo to deliver letters to Augustine from Jerome, and it is generally thought that Augustine approached him at this time regarding writing his history.

Most scholars agree that Orosius' history shows signs of being written in haste and perhaps Augustine wanted it finished quickly so that he could use it as a resource in completing City of God. Other theories suggest that Orosius assisted in writing City of God and his history is written quickly because he was working on two pieces at once. All of this is speculation, however, because all that is really known is that Orosius left Hippo and returned with St. Stephen's relics to Portugal. He then wrote his history and, shortly afterwards, disappeared.

Significance of the History

Orosius' Seven Books of History Against the Pagans was the first world history by a Christian and was completed c. 418 CE, shortly after the sack of Rome by Alaric. Using material taken from Livy, Caesar, Tacitus, Justin, as well as Suetonius, Florus, the Bible, and the History of the Church by Eusebius, Orosius supported his claim that Christianity had done more good than harm in the world and, certainly, had no part in the recent catastrophe for Rome.

Orosius' work is not only a refutation of the pagan claim that Christianity destroyed Rome but also a detailed history which features the Christian god in the role of director of human events. Augustine was interested in a history of the world which would illustrate how God arranged the affairs of nations for his own ends which, though not often clear to humanity, were always for the best. Orosius took this request seriously and began his work with the creation of the world as understood from the Christian perspective. Orosius begins his work, writing:

I shall, therefore, speak of the period from the creation of the world to the founding of the City, and then of the period extending to the principate of Caesar and the birth of Christ, from which time dominion over the world has remained in the hands of the City down to the present day. So far as I can recall them, viewing them as if from a watchtower, I shall present the conflicts of the human race and shall speak about the different parts of the world which, set on fire by the torch of greed, now blaze forth with evils. (Book I, chapter 1:4)

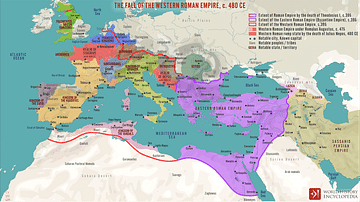

The city Orosius references, of course, is Rome (the 'city' in Augustine's City of God as well) which was considered (with good reason) to be the most important and influential urban center in the world at the time. In Book I, Orosius gives the history of the world from creation to the Great Flood and the early founding of Rome. The second book discusses Roman history up until its sack in 390 BCE by the Gauls and Rome's interactions with other nations afterwards. In the third and fourth books, Orosius deals with Alexander the Great, the rise and fall of nations, and Rome's role in the Punic Wars and the destruction of Carthage. The fifth, sixth, and seventh books focus on Rome from the end of the Third Punic War (146 BCE) to Orosius' time c. 418 CE.

The purpose of Augustine's City of God was to defend Christianity theologically and philosophically against paganism and, specifically, against the accusation that Christianity had played a part in the sack of Rome. The purpose of Orosius' work was to complement Augustine's opus with a detailed history showing how great nations had risen and fallen since the beginning of the world, long before the coming of Christ, and so the claim that Christianity was responsible for a nation's calamities was untenable. Rome fell for the same reasons earlier cities and states had fallen – because God willed it so and God was in control – and not because Christianity had somehow interfered with humanity's relationship with the divine; on the contrary, Orosius pointed out, Christianity had revealed the true nature of that relationship.

The significance of both works, for the authors, was the salvation of souls and the defense of their faith. If the claim that Christianity had destroyed Rome persisted and became more widely accepted, fewer people were apt to embrace the new faith. The fear at the time was that paganism would revive because of the sack of Rome and Christianity would falter, perhaps even fail, and souls which could have been saved would be lost for eternity. The works of both men had to be detailed and precise because the polytheistic religion of Rome had been intimately entwined with all aspects of the people's daily lives and one could not simply claim that this belief had been wrong; one had to prove conclusively that it had been wrong.

Pagan Rome

Rome's polytheistic religion was state-sponsored, and the health of the state was thought to be contingent on the proper observation of religious rites and practices. The gods of ancient Rome were regularly consulted on matters of state, and the priests were thought to be able to accurately interpret the divine will. Whether the question concerned launching a military campaign or building a new complex or planting a certain crop at a certain time, the gods were called upon to render a decision which was then respected and adopted.

One example of the relationship between the temple and state is the Vestal Virgins. These women were the only full-time clergy in ancient Rome and served the goddess Vesta who protected hearth, home, and domestic life. Vesta was considered one of the most important goddesses because her care ensured the peace and tranquility of each of the citizens of Rome and happy individuals created happy communities and encouraged stability and the greater good.

The Vestal Virgins were charged with the responsibility of tending Vesta's sacred flame in the Roman forum, taking care of her shrine and the objects consecrated to her, presiding over ceremonies, and making the special bread served on the feast day of 1 March, the Roman New Year. The virgins (only four or six at any given time) had taken vows of chastity for the duration of their 30-year term of service, dedicating their bodies to the service of Vesta as they had their hearts and souls. The punishment for breaking their vow of chastity was death because they were thought to have not only betrayed Vesta but the state. Their offense against the goddess, it was thought, would ignite her wrath against the city.

If the virgins performed their duties faithfully, Vesta would be pleased and all would be well for the people of Rome. This same paradigm held for the other gods and goddesses of the Roman pantheon. The state mandated the specific rites and types of behavior acceptable to the gods, sponsored festivals and feast days for the gods, and sacrificed regularly to the gods, in the sure knowledge that their gods, in turn, would protect and help them in times of need. This quid pro quo relationship (this-for-that) only worked, however, if the people of Rome held up their end of the bargain. Christianity, the pagans claimed, had caused them to fail in this and brought Alaric to Rome as punishment.

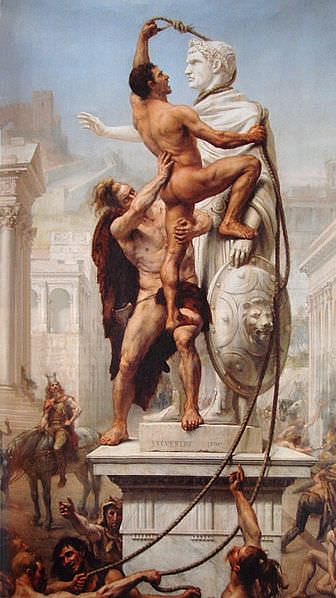

Alaric's Sack of Rome

As the Roman Empire expanded, it required more and more men for military service and began employing more and more mercenaries in its army. Mercenaries were nothing new to the Roman war machine – Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) had employed mercenaries on his campaigns – but the number of these types of soldiers increased in step with the empire's expansion. By the time of the 3rd century CE, mercenaries outnumbered Romans in the army and many of these were Goths.

In the late 4th century, the Goth king Alaric I joined his army with Rome's as a mercenary contingent in the civil war between Theodosius I of the Eastern Roman Empire (r. 379-395 CE) and Eugenius of the Western Roman Empire (r. 392-394 CE). Alaric's decision was not voluntary as it was a stipulation of a treaty between the Goths and Rome from 382 CE that the Goths could settle in the Balkans (as allies, not full citizens) in exchange for military service. At the Battle of the Frigidus in 394 CE, Alaric's troops fought for Theodosius I but were placed in the front lines as, essentially, fodder for the enemy's missiles. Theodosius I's forces won the battle – allegedly with divine assistance – but Alaric's losses were heavy.

A few months after the battle, Theodosius I died, leaving his two young sons to the care of his general Stilicho (l. 359-408 CE). Stilicho, therefore, became regent for Theodosius I's young heir Honorius (r. 395-423 CE). Alaric, in an attempt to recoup his losses and force Rome to reconsider the terms of the 382 CE treaty, initiated a series of raids in the Balkans, which he claimed would cease if the Goths were provided with grain and full citizenship as Romans. Stilicho refused this request, and the raids continued while Alaric sent another message requesting 4,000 pounds of gold.

Stilicho, at this point, was going to concede but the Senate overruled him and declared Alaric an enemy of the state. One of the senators, Olympius, gained the trust of young Honorius and persuaded him that Stilicho was in league with Alaric. In 408 CE, Olympius orchestrated the massacre of Goth mercenaries serving in the Roman army and Stilicho himself was among the victims. Tired of Roman machinations and duplicity, Alaric invaded Rome in 410 CE, sacking the city.

This event was, naturally, considered a great tragedy by the Romans who struggled to understand how and why it could have happened. They had, after all, always done best to keep their part of the bargain with the gods but these deities had seemingly betrayed them to their enemies. The practical, earthly, sequence of events which led to the sack of Rome was completely ignored in the quest to find some supernatural explanation for the catastrophe, and the answer which suggested itself was that the Christians were to blame for angering the gods by ruining Rome's relationship with the divine through their new faith.

The Pagans vs. Orosius

The pagans pointed out how Christians had refused to participate in festivals, refused to sacrifice to the gods, even mocked the gods, and so negated the contract between the gods and Rome by angering them. The gods of Rome had traditionally been kind to the city, they pointed out, protecting it from invaders for over 800 years, and the Christian faith was an ungrateful affront to the centuries of kindness and love the gods had shown to the city. Every aspect of Roman life came from the gods – from one's home life to that of the state itself – and had due respect and honor continued, the sack of Rome would never have taken place.

Orosius attempted to show how, long before Christianity appeared on the world stage, great nations and states had collapsed while worshipping gods quite similar to those of Rome in very similar ways. If these earlier nations had fallen while engaged in polytheistic religious belief and rites, why would Rome be an exception? Far from Christianity being to blame for Rome's fall, it was far more likely the Roman stubbornness in refusing to accept the revelation of God through Jesus Christ was the true cause. Rome had worshipped false gods and devils for centuries and, when the true god appeared, he was rejected in favor of the comfort of tradition and false idols.

Conclusion

Orosius' work was published around the same time that Christianity was gaining momentum. In 415 CE, the pagan philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria was murdered by a Christian mob in Egypt and pagan temples and libraries looted. Orosius himself alludes to such events in his work, claiming it was a shame that books had been lost through the zeal of Christian brothers. Christian churches were replacing pagan temples across the ancient world when Rome was sacked, and it was for this reason that a defense had to be mounted by Augustine and Orosius to make sure that momentum continued.

Seven Books Against the Pagans became very popular upon publication and, owing to Orosius' friendship with and patronage by St. Augustine, was accepted easily by the early church as 'true' history and, eventually, found its way into the accepted history of the fall of the Roman Empire until Edward Gibbon published his famous six-volume The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (between 1776 and 1788 CE) which presented a vastly different view of the situation and has, since, influenced other historians to re-evaluate Orosius' interpretation of earlier sources. Even so, Orosius remains an important writer of his time, and his work is still often referenced in theological, philosophical, and historical works.

Of equal importance, Orosius' history provided ancient historians a guide for writing history as well as for map-making. Orosius' detailed description of the geography of the ancient world provided map-makers with much-needed information well into the Middle Ages and beyond. The famous Hereford Mappa Mundi (Hereford map of the world, c. 1300 CE) credits Orosius as its source.

Although much has been made of the Christian vision of Seven Histories Against the Pagans and the City of God, Orosius and Augustine were really trying to explain an aspect of the human condition which still upsets and confuses people – of all faiths or none – in the present day: why bad things happen to good people. Augustine freely admitted that bad things happen to all kinds of people – good and bad, Christian and pagan – all the time, and Orosius illustrated that point through his history. Neither author, however, was able to answer to question of why seemingly good people suffer or why seemingly bad people prosper just as no one has provided an adequate answer to that question up to the present day.