Orpheus is a figure from ancient Greek mythology, most famous for his virtuoso ability in playing the lyre or kithara. His music could charm the wild animals of the forest, and even streams would pause and trees bend a little closer to hear his sublime singing. He was also a renowned poet, travelled with Jason and the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece, and even descended into the Underworld of Hades to recover his lost wife Eurydice. Orpheus was seen as the head of a poetic tradition known as Orphism where, according to some scholars, adherents performed certain rituals and composed or read poems, texts, and hymns, which included an alternative view of humanity's origins. Orpheus is widely referenced in all forms of ancient Greek art from pottery to sculpture.

Family

Orpheus had an excellent musical pedigree as his mother was the Muse Calliope and he learnt his great skills from his father the god Apollo, the finest musician of them all. Orpheus' mortal father was generally considered to be King Oeagrus (or Oiagros) of Thrace, where the Greeks believed the lyre also came from. Orpheus' brother was the unfortunate Linos (Linus) of Argos, the inventor of rhythm and melody, and the kithara teacher of Hercules, who was killed by his famous pupil after he over-chastised the hero. Orpheus also passed on his musical skills, notably tutoring King Midas, the mythical king of Phrygia whose touch changed everything into gold. In some myths, Orpheus had a son, Leos who was regarded as the founder of the Athenian Leontids.

The Argonauts

Orpheus visited Egypt but then returned to Greece to become a member of Jason's expedition to find the Golden Fleece in Colchis on the Black Sea. The talented virtuoso not only entertained the Argonauts but also kept time for the rowers of the Argo ship and even ended a few drunken brawls amongst the mariners with his gentle notes. It was also said that he even calmed the seas with his seductive singing and charmed the terrible Sirens who tempted sailors to their deaths. The story is an early example of the ancient Greek's faith in the magical powers of music.

Eurydice in Hades

Orpheus married Eurydice (aka Agriope); however, their happiness was short-lived, for Eurydice was bitten on her ankle by a poisonous snake when attempting to escape an attacker, the demigod Aristaeus. Eurydice died, in some accounts, on her wedding night. Distraught, Orpheus followed his love down to Hades, the Greek Underworld, and with his music charmed Charon, the ferryman, and Cerberus, the fearsome dog which guarded the gates, to allow him into the realm of shades. Meeting Persephone, the wife of the god Hades, he beseeched the goddess with his song to release Eurydice and allow her to return to the land of the living. Hades, who ruled the Underworld, then appeared and, moved by Orpheus' offer that if Eurydice could not be released, he would stay himself in the Underworld, the god consented to her release. There was, however, a condition. The shadow of Eurydice would follow behind Orpheus as he left Hades, but if he once looked back at her, she would forever remain in the world of the dead. Delighted, Orpheus agreed to this simple request but as he walked through the shadows of Hades and heard not a single footfall from behind, he began to doubt Eurydice was still there following. Then, almost at the threshold of the world of light and happiness, the doubtful Orpheus looked back. There she was, the shadow of Eurydice, but as soon as their eyes met, the girl vanished. In despair, Orpheus stumbled to the daylight and collapsed, his grief not allowing him to eat or drink. Finally, he gathered his senses and roamed the forests of Thrace, but he shunned human company and never sang or played his lyre again.

Maenads & Death

Orpheus' misery would soon end, though, when he was set upon by a group of frenzied Maenads (the female followers of Dionysos, the god of wine). They stoned him to the ground and ripped him to pieces for his lack of merriment (or homosexuality in some interpretations). In some versions of the myth, Dionysos had sent his followers on their terrible task because Orpheus had preached to the people of Thrace that Apollo and not Dionysos was the greatest god. It is interesting to note that in the Bronze Age, fugitive priests from Egypt did settle in the northern Aegean and brought with them worship of the sun god Amun. This also explains the element of the Orpheus story that he once visited Egypt. According to Plutarch (c. 45-50 - c. 120-125 CE), the Maenads were punished for their crime by being turned into trees. Other Thracian women had their bodies tattooed by their husbands as a warning not to repeat such a crime - a cultural practice in the region stretching from antiquity to modern times.

All this did not help Orpheus, of course, and limbs of the unfortunate musician were carried out to sea (or were buried at the foot of Mount Olympus) while his head, still whispering his lover's name, was said to have washed up on the island of Lesbos where the Muses buried it. At this spot, they also built a shrine on which birds would sing in such a fashion as to recall the fabulous lost talent of Orpheus. In (yet another) version of events, Orpheus' head became an oracle of Apollo but the god soon tired of the competition with his other oracles at Delphi and elsewhere and so buried it. The great musician's lyre was smashed by the Maenads in some accounts, whilst in others, it is also washed up on Lesbos, discovered by a fisherman, and given to Terpander, the famed 7th-century BCE musician and poet of that island. In an alternative version, the lyre of Orpheus was made into a constellation by Zeus in lasting recognition of a great musical gift.

Orphism

Even the ancient Greeks themselves were divided over whether or not Orpheus had existed in some form or another and written surviving poems. Both the historian Herodotus (c. 484 - 425/413 BCE) and the philosopher Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) deny that Orpheus ever wrote hexametric poems, for example. There was, though, a movement of some sort which is called Orphism by modern scholars, who still debate its significance. Some historians believe nothing more than the name Orpheus connected various poets and practisers of rituals, some suggest it was merely an aspect of mystery cults focussed on Dionysos, while still others suggest that communities did form with specific texts (Orphica) and rites. The latter view has recently been supported by archaeological finds such as the Derveni Papyrus which mentions a specific group of Orphic deities, a number of 400 BCE gold leaves (from northern Greece, Crete, and southern Italy) inscribed with instructions on how the soul should behave in the Underworld, and 5th-century BCE bone tablets discovered in Olbia (Crimea).

The texts that these adherents to Orphism revered and produced included poems, rites, and hymns, which often describe the origins of the gods and frequently contain references to secrecy and hidden meaning. The origins of humanity are told differently compared to other works of Greek literature such as the Theogony of Hesiod (c. 700 BCE). In the orphic tradition, the Titans (persuaded by Hera) cook and eat Zeus' son Dionysos and, for this, they are punished, Zeus striking them down with his thunderbolts. While Dionysos was reborn from the only original part left of the god - his heart - humanity sprang from the dust of the Titans. However, humans must now atone for both the crime of their progenitors and for that 'Titanic' streak in their character which they have inherited from them. The atonement must be done in this life - through rituals of purification - in order to be ready for the next. The idea of an inherent negative facet of human nature and the need to atone for it in some way was influential on later religions, especially Christianity. A minority of scholars suggest that this interpretation of humanity's origins and its consequences, which differs from the more widely known and accepted Greek theogony, is merely a modern one but there are references to it in several ancient writers from Plato (c. 428 - c. 347 BCE) to Plutarch.

In Art & Culture

Aside from music, Orpheus was considered the first Greek poet who passed on the artistic mantle to the mythical singer and poet Musaeus, who, in turn, passed it on to the more familiar Hesiod and Homer. Orpheus is mentioned as such, albeit rather negatively, by both the philosopher Plato (Protagoras and Apology) and the writer of Greek comedy plays Aristophanes (c. 460 - c. 380 BCE), for example, Frogs. Orpheus was also credited with the powers of prophecy, and some traditions credit him with giving the human race the gifts of agriculture, medicine, and writing.

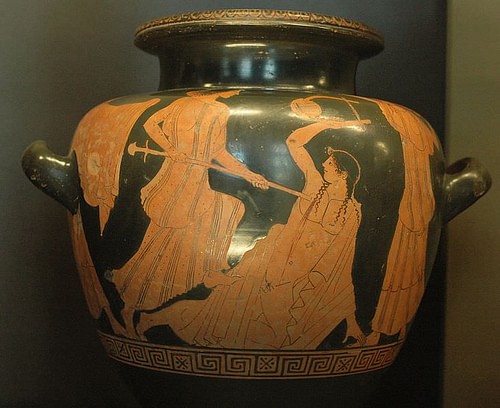

In ancient Greek art, Orpheus is, unsurprisingly, usually depicted with his lyre or kithara close at hand, and from the 4th century BCE, he is sometimes seen wearing Thracian dress. On red-figure pottery, scenes from the Eurydice myth are popular as are scenes of the musician's death, attacked by ferocious women (although interestingly, none ever have the attributes of Maenads).

![The Greek Myths: The Complete and Definitive Edition [May 15, 2018] Graves, Robert](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51QGERJF7lL._SL160_.jpg)