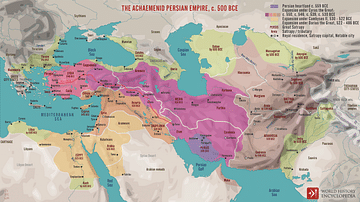

The Oxus Treasure is a collection of 180 artifacts of precious metal, dated to the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), which were discovered on the north bank of the Oxus River near the town of Takht-i Sangin in Tajikstan between 1876-1880 CE (commonly given as 1877 CE). The bulk of the collection is presently housed in the British Museum, London.

The treasure is thought to have once been owned by a temple – quite possibly a nearby temple – which was looted and the hoard then buried to be retrieved later. Conversely, it is possible the treasure was taken from a temple and hidden to prevent just such looting. The original provenance of the collection is unknown as is the exact spot where it was found, who found it, and what the original find might have been comprised of.

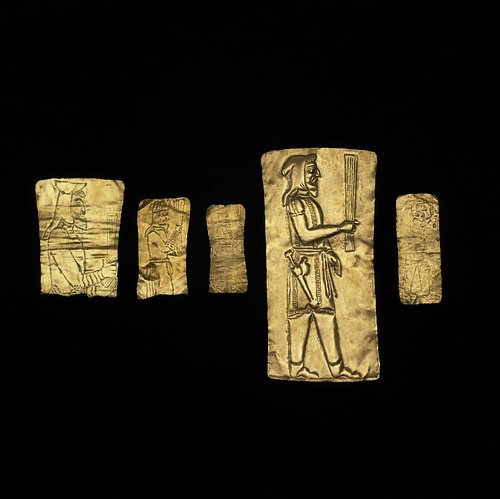

The connection of the treasure with a temple is suggested by the 51 gold-sheeted votive plaques which form part of the collection and by some of the figurines/statuettes which suggest devotional figures placed in holy sites. It is possible – though far from provable in any way – that the treasure was looted from a temple by the Seleucid king Antiochus III (the Great, r. 233-187 BCE) following his defeat by Rome at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE.

Following this event, and the Treaty of Apamea of 188 BCE, Rome placed the burden of a heavy war indemnity on the Seleucids which Antiochus III struggled to pay and so resorted to looting temples of their treasures. Antiochus III, in fact, was killed in 187 BCE while engaged in this kind of activity. The Oxus Treasure could have been among the loot taken at this time and buried near the fort of Takht-i Kuwad on the Oxus near to the town of Takht-i Sangin - which was a documented ferry station and would have been easily remembered by whoever buried the hoard - but this is speculative.

Although some scholars have challenged the find as fake – notably the American scholar Oscar Muscarella as recently as 2003 CE – the general consensus is that it is genuine, dates from the Achaemenid Period, and is representative of some of the finest art in metallurgy from that time.

The Treasure & Achaemenid Association

The Oxus Treasure includes but is not limited to:

- 2 gold model chariots with horses and figures

- 1 scabbard for a short sword (the akinakes) ornamented with a lion-hunting scene

- Figurines/statuettes of human beings – devotional in nature

- Figurines/statuettes of human beings – non-devotional

- Animal figurines

- Drinking vessels of gold and silver with attachments (handles)

- Other vessels of gold and silver

- Clothing appliques (ornaments/clasps for clothing)

- Torques (ornamental neck-rings)

- Finger rings and seals

- 2 golden armlets with griffin terminals once inlaid with gemstones

- 51 sheets of thinly pressed gold votive plaques

- Assorted pieces of gold and silver

- 1 golden fish ointment/perfume container

Other items are mentioned in the reports of the initial find which began appearing in correspondence in 1879 CE. A figure of a golden tiger, for example, is mentioned in these early reports but this item has never been catalogued and seems to have disappeared early on. Other items which were initially mentioned may have been lost to thieves or melted down by whoever originally found the lot, and it is known that some coins and other artifacts were purchased by British soldiers in the region.

The treasure is linked to the Achaemenid Period because many similar artifacts are pictured in Achaemenid art, especially in the bas-reliefs at Persepolis, and similar finds have come from excavations at Susa and elsewhere. The scabbard, for example, is similar in every way to one depicted in the reliefs at Persepolis. Who made these works, or where, is unknown but it is believed they were owned and worn by Achaemenid royalty. In discussing finds from the Susa tomb, as well as the Oxus Treasure, scholar Francoise Tallon writes:

The charter for the Palace of Darius states that Egyptian and Median goldsmiths, then considered the most skilled artisans in the trade, worked on the decoration of the palace. Yet there were certainly many centers for the production of precious objects. On the reliefs in the apadana at Persepolis, several delegations can be seen bringing bracelets (the Medes, the Scythians, and perhaps the Sogdians) or vessels of silver and gold (the Lydians and the Armenians). On the other hand, texts from Persepolis mention Carian goldsmiths. It is therefore difficult to attribute the manufacture of these jewels to a specific region because their style and iconographic motifs were common all across the empire, and they were made using techniques that had long been mastered throughout the Near East. (Harper, 242)

Following the Oxus Treasure find, the French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan unearthed the tomb of an Achaemenid noble on the acropolis at Susa in February 1901 CE. The tomb held a skeleton adorned with gold and silver jewelry accompanied by a silver bowl, alabaster vessels, and other grave goods. This find on its own would have been impressive enough but it substantiated the claim of some of the scholars at the time that the Oxus Treasure was also Achaemenid owing to the similarities of the Susa tomb grave goods and the treasure found by the river.

Treasure in Detail

Among the most impressive pieces are the model chariots, the griffin armlets, the scabbard, and the golden fish – although other pieces are nearly as remarkable. The figurines and votive plaques, for example, even those exhibiting a much rougher form of execution, are still impressive.

Model Chariots

There are two model chariots, both in gold, one incomplete. The chariots are pulled by intricately modeled horses and the carriage holds two figures – a driver and passenger – both of whom are depicted in detail down to their facial expressions. The horses, also, are detailed in their posture and gait. The carriage is ornamented with an image of the Egyptian god of fertility, Bes, on the front and designs on both sides while the wheels are spoked and beaded along the rims. The reins held by the driver are varied in presentation to create the illusion of motion.

Griffin Armlets

The Griffin Armlets are equally impressive, once inlaid with precious stone, and still resonant even in semi-ruin. The armlets were once adorned with inlays of gems and colored stones which have since fallen out and been lost. Scholar Edith Porada, among others, notes how the armlets especially “preserve Achaemenid and other motifs employed according to the taste of the region” which favored “strong colors” and “abstract stylization” characteristic of Scythian art but favored by the Achaemenids (174). It is possible, then, the armlets – and other pieces of the Oxus Treasure - were Scythian in origin but, as Tallon notes above, positive identification of origin is not possible owing to the fairly widespread skill of artisans working in gold in the region.

Scabbard

The scabbard is often identified as a “dagger scabbard” but this designation mistakes the Persian short sword (the akinakes) for a dagger. The scabbard is decorated with a lion-hunting scene and corresponds closely to one seen in the Persepolis reliefs where the armor-bearer of Darius I (r. 522-486 BCE) is wearing one. Porada, and other scholars, identify the scabbard design as Median in origin which supports the claim that the Oxus Treasure is Achaemenid since Cyrus the Great drew on the Median paradigm regularly in forming his own empire.

Golden Fish

The golden fish is 9.5 inches (24.2 centimeters) long and weighs 370 grams. It is hollow with an open mouth and a loop by which it would have been suspended. It is thought the piece held oil or perfume. The fish has regularly been identified as a carp but, in 2016 CE, writer and fishing enthusiast Adrian Burton identified the object as representing the Turkestan barbel, a fish endemic to the Oxus River and a much clearer model for the golden fish than the carp.

Figurines

A number of the human figurines are devotional – meaning they were made to represent people in attitudes of prayer at a temple – while others seem either merely decorative or, perhaps, representative of some individual. The devotional figurines are among the items identifying the Oxus Treasure with a temple treasury. The practice emerged in Mesopotamia during the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) among the elite who commissioned statuettes of themselves, made from gypsum or limestone, to be brought into the presence of a god in a given temple.

Mesopotamian religious rituals were not congregational in nature – a lone priest/priestess or group of clergy tended to the deity's statue in the temple – and so figurines were created which would represent an individual and could be placed in a shrine to petition a god directly. The devotional (votive) figurines of the Oxus Treasure follow the same basic model as Mesopotamian votive figures but are made of gold or silver. They were most likely used for the same purpose as in Mesopotamian temples. The purpose of the non-votive figures from the Oxus Treasure is unknown. It is possible they were memorial figures of the deceased.

The animal figures, such as horses, were most likely pendants/amulets and continue a tradition of using animal motifs in art begun in the Proto-Elamite period of the region of Iran. The image of a dog, for example, would ward off evil spirits while the image of a horse might encourage speed or stamina.

Votive Plaques

The 51 votive plaques are the other significant portion of the treasure linking it to a religious site. The plaques are rectangular sheets of gold depicting mostly human figures carrying barsom twigs, an offering to the gods which represented the earth and its bounty and was associated with deities such as the goddess of fertility, water and wisdom, Anahita. Some of the plaques show animals instead of humans which, again, hearkens back to the Proto-Elamite custom of depicting animals in art which symbolized one concept/characteristic or another. In Elamite art, animals would sometimes stand in for people and those depicted on the plaques could have represented some specific petition for strength or health or courage.

Elamite art influenced Scythian and Median art which, in turn, affected the work of Persian artisans. Porada notes:

Just as the Medes probably handed down to the Persians the elements of Scythian art which they had absorbed or obtained independently through eastern connections, so they must also have been the middlemen for the continuation in Achaemenid art of other stylistic traditions which prevailed in Iran in Median times. (146)

The plaques have commonly been identified as Median in style but this does not necessarily mean they were created by Medes. They were most likely commissioned by wealthy Persians to represent their petitions to the gods. Some of the plaques were clearly made my amateurs working in a medium they were unfamiliar with as they exhibit a low level of skill. These may have been created by people unwilling to pay an artisan to do a job they felt they could take care of themselves.

Jewelry and Vessels

Besides the griffin armlets, there are a number of pieces of jewelry and appliques in gold and silver. Some of these feature the Egyptian fertility god Bes and others draw on the animal motif. Among the most interesting is a gold ring with a creature often identified as feline but which is more likely an image of the dog-headed bird Simurgh, a benevolent entity from Early Iranian Religion who would be invoked in times of need. Wearing a ring with an image of Simurgh would have been comparable to carrying a good luck charm in the present day. There are also torques included among the jewelry which, stylistically, correspond to the lion-headed torque from Susa and show the same high level of craftsmanship.

The drinking vessels are bowls and jugs, most likely used for wine, and similar in design to the bowls found in the Achaemenid tomb at Susa. A significant difference is that the Oxus vessels seem to have been handcrafted individually in gold whereas the vessels from Susa were cast (as evidenced by a standard floral design on the bottom exterior which is not repeated in the interior). These artifacts, like many of the others, would have been given to the temple as gifts in gratitude for a prayer answered or in supplication for a petition.

In addition to the above, there are assorted stray pieces of gold and silver charms, amulets, and buttons. Initially, it was thought that 1,500 gold coins were also part of the original find, but this claim has been challenged and, today, the coins are thought to have been added to the collection later from another provenance.

Discovery

No one who was part of the initial discovery is identified as participating in the treasure's history afterwards, and there is no mention in the records of who, or how many, people were involved or what the circumstances were which led to the find. Later claims give accounts varying from villagers finding the treasure in the riverbed, to the hoard only being revealed during either a drought or the dry season which lowered the river's level, to a slip of land dislodging from the riverbank and revealing it. How and where the Oxus Treasure was found will probably never be known.

According to scholar John Curtis, the first mention of the treasure appears in the Numismatic Chronicle of 1879 CE, Volume 19, in which one Percy Gardener mentions how “a large hoard of gold and silver coins” were discovered “eight marches beyond the Oxus at an old fort, on the tongue of land formed by joining rivers” (295). This find was originally identified as Seleucid, dating to the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE), the polity founded after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE.

Later in 1879 CE, a Russian Major-General N. A. Mayev reported that he had excavated a site at the Oxus near the ancient fort of Takht-i Kuwad and spoke with local inhabitants who informed him that treasure had been found there in the past, including a large golden tiger, which had all been sold to “Indian merchants” (Curtis, 296). In 1880 CE, the Lahore Civil and Military Gazette for 24 June reported a robbery of substantial sums of gold from Indian merchants in Kabul, Afghanistan. A British officer stationed in the region, Captain Francis Charles Burton, pursued the thieves and retrieved most of the treasure, returning it to the merchants, who sold him one of the armlets from the collection; this brought the find to the attention of British authorities and, notably, Sir Alexander Cunningham (l. 1814-1893 CE) who had been appointed archaeological surveyor of India and had extensive historical and archaeological knowledge of the region.

Cunningham purchased a number of pieces from the merchants, and the British antiquary Sir A. W. Franks (l. 1826-1897 CE) bought most or all of the rest. Franks eventually purchased Cunningham's pieces and, as an administrator of the British Museum, bequeathed his collection to that institution. By 1881 CE, there was already disagreement on what constituted the Oxus Treasure as Percy Gardener notes in another volume of the Numismatic Chronicle (Volume 1, 1881) that the coins which were originally thought to be part of the original find did not correspond to the rest of the hoard, having their provenance in Cilicia and elsewhere. Gardener theorized that the merchants added the coins to the original hoard to increase its value (Curtis, 297). Cunningham disagreed, claiming that the majority of the coins belonged to the original find. The origin of the 1,500 gold coins has now been commonly accepted along the lines of Gardener's theory and are not considered part of the Oxus Treasure.

Conclusion

Controversy over the unity, and even the authenticity, of the collection, continued into the 21st century CE. The most famous conflict was initiated by scholar Oscar W. Muscarella who is well known for his efforts to prevent looting of archaeological sites and, further, his work in identifying modern forgeries. Muscarella claimed that the unity of the Oxus Treasure could not be substantiated – citing the unknown provenance of the find and the confused route it took to the hands of Cunningham and Franks – and that, further, many pieces (such as a number of the more amateurish votive plaques) were modern fakes. In spite of his reputation in the field, his claims were dismissed and the treasure is regarded as an authentic collection of Achaemenid Period artwork which was discovered and legally purchased in the late 19th century CE as per the reports of Cunningham and Franks.

In 2007 CE, the President of Tajikstan, Emomalii Rahmon, called for the return of the Oxus Treasure to his country, but his request was denied on the grounds that the artifacts were legally purchased by the British Museum. In 2011 CE, the museum agreed to send replicas of the artifacts to Tajikstan for display in their National Museum, and this agreement was concluded in 2013 CE. The bulk of the find remains in the British Museum with some artifacts held in exhibit by other institutions. Since the accounts of the initial find, the unity of the collection, and its acquisition by Cunningham and Franks have all been accepted as valid, these have become the official history of the Oxus Treasure in the modern era; whether these accounts are accurate is now impossible to determine.