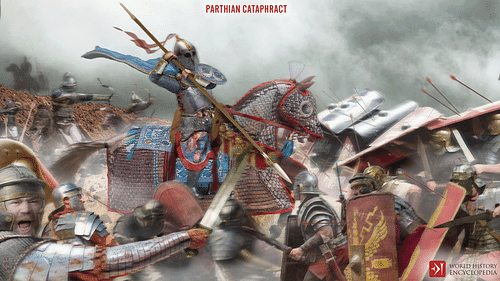

The Parthian Cataphract was a heavy cavalry unit of Parthian warfare, an entirely armored, huge fast horse mounted by a completely armored rider, equipped with a long lance and a long sword. Like a modern tank designed to smash through enemy defenses, the integrated tactical use of the cataphract was something the Parthians brought to a new level in battle.

Tactics

Working in concert with their light cavalry, when they were not mopping up fleeing combatants, the cataphracts, as Cassius Dio relates (40.22), ran pell-mell, with their heavy horse, into an enemy formation. Such a massive animal at top speed would, like a bowling ball, have scattered soldiers left and right, even causing those near the area of impact to be jostled. Multiple cataphracts attacking a formation at once would have had a devastating effect up and down a line of defense. Besides those directly killed or trampled, with bodies flying, fighters fleeing, and shields down, the cataphracts would have created gaps of vulnerability into which their horse archers shot arrows from their "mighty bows" (Plutarch, Crassus, 24.4-5).

The Parthians thus fielded a formidable military machine consisting primarily of cavalry, as "their cataphractii defeated the Seleucids in western Iran and Mesopotamia in the 2nd century BC" (Farrokh, 4). Moreover, a match for Roman warfare, they defeated Mark Antony in 36 BCE. Although little is known about the part their cataphracts played in that and other battles, their use, and appearance are best known from Plutarch's description of the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, the cataphract graffito from Dura Europos from their later reign, and the Firuzabad rock relief of their final defeat by the Sassanians in 224 CE.

Armor

While there is some debate distinguishing cataphracts from heavy cavalry, which consisted of varying degrees of armor for the riders and their larger horses while employing a variety of weapons, much can be learned about the narrower use and distinct appearance of the cataphracts at Carrhae, in modern Turkey. There Surena commanded 1,000 Parthian cataphracts and 9,000 horse-archers against Marcus Crassus' over 30,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.

Before the battle unfolded, Surena performed some astounding psychological warfare. Plutarch notes that, before the Romans approached, Surena hid the bulk of his force behind his advance guard so his army would appear small. Then, "to confound the soul and unseat judgment," the Parthians filled the plain with a deafening beat of kettledrums – their noise "like the bellowing of beasts mixed with sounds resembling thunder" (23.7). Before their closing with the already unnerved Romans, Surena had his cavalry cover their armor with skins and robes. Then, as they got near, after spreading their troops out, they took the wrappings off and showed the Romans their "blazing helmets and breastplate; their Margianian steel glittering keen and bright" (23.6-24.1).

The moniker 'Margianian steel', like 'Damascus swords' or 'Corinthian helmets', suggests a higher quality product. Interestingly, as high-grade steel is stronger and less prone to corrosion, it keeps and displays a keener sheen. Though such products were expensive and the cataphract riders paid for their own outfit, with Surena, the wealthiest of Parthians (next to the king) at their head, they apparently could afford and chose the 'Margianian steel'. Moreover, that their helmets and breastplates shone so brightly suggests a fuller surface of reflection, something full helmets and cuirass-like breastplates would do.

Later in the same battle, Plutarch mentions breastplates again, including leather ones. Like many armies of antiquity, there was a varying standard of equipment. Perhaps the poorer nobles could only afford the cheaper but still effective leather breastplates. Interestingly, the word 'cuirass' carries a leather construction etymology. The idea and advantage of one-piece protection of the most critical vitals – the head and heart – with fewer points of entry, was realized early on. Cuirasses can be traced to classical antiquity, with surviving Greek ones dating to 620 BCE. As vassals and then conquerors of the Seleucid Empire, such products would have been familiar to and likely used by the Parthians. Even their conquerors used them. Carved to celebrate Sassanian victory over the Parthians in 224 CE, the Firuzabad relief in Iran shows full breastplates on Sassanian and Parthian riders alike.

Along with the helmets and breastplates, Plutarch also mentions the use of mail. Likely invented by the Celts and one of the most popular forms of personal armor, mail consisted of tiny metal rings joined together to form a metal fabric. Worn like clothing, mail provided the wearer a higher degree of maneuverability than lamellar and laminar armor. One of the pivotal moments at Carrhae was when, after Crassus' main body was pummeled and pinned down by the arrows of Surena's horse-archers, Publius Crassus, with Roman cavalry, broke out in chase after the Parthian cataphracts. As the Parthians led Publius on for some distance, "their mail-clad horsemen" suddenly whirled about to confront the Roman army (25.4). The Parthian horse-archers kicked up a huge cloud of dust, causing the Romans to close rank in confusion, which made them easy targets. Desperate to escape this mess, Publius once more charged the cataphracts, but the "mail-clad horsemen" with their longer "pikes" made it a no-contest (25.6-7, 27.1).

The Firuzabad relief clearly shows the use of mail with breastplates. Thus it is probable the appearance of Surena's cataphract riders at Carrhae included full helmets and combined use of mail and breastplates. In preparation, they would at first have dressed in their usual tunic and trousers. They then would have covered themselves head-to-ankle with mail, and over that, they wore the breastplate and helmet. Finally, keeping in mind that the Roman legionary would slash and stab at anything and everything, extra protection of shins, arms, hands, and feet would likely have been employed.

Plutarch describes Parthian horses "clad in plates of bronze and steel" (24.1), Herodotus mentions the early use of scale armor by Persian soldiers (Histories, 7.61), and images like the Dura Europos drawing of a Parthian horse and those of Sarmatian horses on Trajan's Column suggest scale was a popular choice. Consisting of overlapping metal plates sewn onto a cloth or leather undergarment, the Parthian heavy horse was, except for legs and tail, enveloped in scale.

Saddles

While stirrups appear to be a later advent and no period artifact shows them available for the Parthians, saddles are another story. Some ancient images appear to show Parthian riders without them, but archaeological evidence concerning their availability is definitive. An important innovation before stirrups was the integration of the pommel and cantle onto the rider's seat. These help the rider to stay on when jostled, give stability when the horse brakes, and assist maneuverability in a turn. According to Elena Stepanova's detailed re-creation, based on finds dating to the 4th century BCE, the Scythians crafted an ingenious four-part saddle of split pommels and cantles. The design itself reveals the rider's purpose: turning and directional changes as well as swift acceleration. Such saddles are also found on the Black Sea Bosporan reliefs of Cimmerian horse-archers dating to the 2nd and 1st century BCE.

While these saddles were probably for light-horse cavalry, Parthia's heavy cataphracts would have needed a simpler design. Given their head-on impact and extraction purpose, a robust two-part design is probable. While the cantle and pommel helped cradle the rider on impact, the pommel would keep the rider from being unhorsed as he pulled back from the melee. A substantial pommel and possible cantle appear evident on the swift Sassanian riders from the relief at Firuzabad, Iran. Ongoing Parthian-Scythian relations and the fact that Parthia's conquerors used saddles make it likely the Parthians did, too.

Changes

While heavy cavalry could perform different purposes, the Parthian cataphract, defined as a tank of sorts, was meant to punch through enemy lines. As it is the nature of warfare, countering tactics combined with intellectual and material innovation all add to the ongoing changing nature of any military asset, defensive or offensive, and so the Parthian cataphract evolved. Even at the Battle of Carrhae, things quickly changed. As Crassus smartly stacked the depth of his front lines into a column formation in anticipation of cataphract impact, Surena chose to put his cataphract tanks on hold and instead unleashed a punishing array of arrows from his horse-archers. Anticipating a breakout of Crassus' heavy cavalry, Surena's cataphracts, feigning retreat, ran the Romans into an ambush of more arrows and one-on-one heavy cavalry combat.

As to change in personal armor, comparing the Dura Europos and Firuzabad images with Plutarch's account, interesting developments occur. The disadvantage of mail is that it is heavy on the shoulders, besides allowing blunt force injury. It appears the Parthians addressed this problem on the Dura Europos image with laminar protection of the arms, legs, and feet. While using mail to protect the head and neck, the upper torso is also guarded with mail, the weight of which is carried by a girdle of lamellar plates protecting the lower torso. Yet the Firuzabad relief clearly shows both Parthian and Sassanian riders wearing breastplates. Additionally, at Firuzabad, the Sassanian riders use mail for arm and leg protection and wear only headbands, while the Parthian uses laminar armor and dons a full helmet with scale protection for the neck. Sporting their fashionable diadems, the Sassanian king Ardashir I and his son Shapur I do not seem to be worried about strikes to the head or neck.

Tactics-wise, if there is one impression the Firuzabad relief means to show is the swiftness of their riders and steeds. With their horses in mid-air at full gallop, their tails horizontal, and the rider's hair and scarfs swept behind, the swiftness of their cavalry is apparent. Thus, it appears the Sassanians employed a change of use. Overall, there seems to be a lightening of the load for speed. The Taq-e Bostan image from the 4th century CE shows a Sassanian cataphract horse with front armor only, of what appears to be a gambeson of padded cloth. Not only does this reveal less weight but also an end to the tactic of full penetration into enemy ranks and the ensuing melee. It appears the heavy cataphract, used as a tank to break infantry lines would finally go from select to little use until the Middle Ages with comparable implementation in Byzantine warfare.