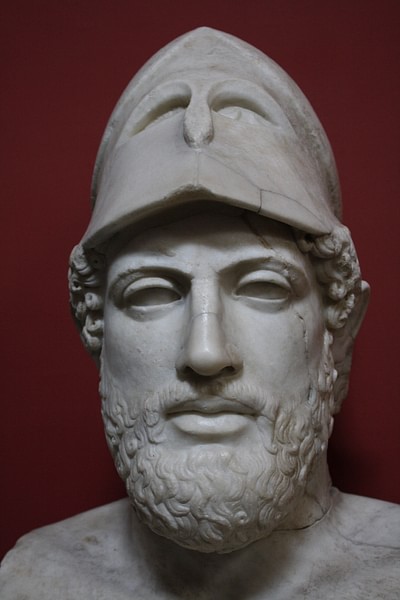

Pericles (l. 495–429 BCE) was a prominent Greek statesman, orator, and general during the Golden Age of Athens. The period in which he led Athens, in fact, has been called the Age of Pericles due to his influence, not only on his city's fortunes, but on the whole of Greek history during the 5th century BCE and even after his death.

He was a fierce proponent of democracy, although the form this took differed from the modern day as only male citizens of Athens could participate in politics. Even so, his reforms would lay the groundwork for the development of later democratic political systems.

Pericles' name means "surrounded by glory" and he would live up to his name through his efforts to make Athens the greatest of the Greek city-states. His influence on Athenian society, politics, and culture was so great that the historian Thucydides (l. 460/455 - 399/398 BCE), his contemporary and admirer, called him "the first citizen of Athens" (History, II.65).

Pericles promoted the arts, literature, and philosophy and gave free rein to some of the most inspired writers, artists, and thinkers of his time. According to his contemporaries and later writers, he was encouraged and directed in this, as well as in other aspects of his career, by his consort Aspasia of Miletus (l. c. 470-410/400 BCE) who seeems to have served as the muse to many famous Athenians of the time.

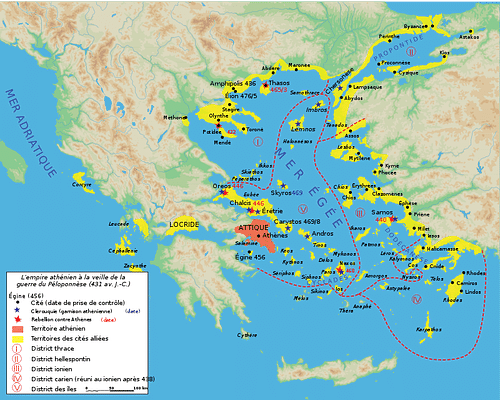

The degree of influence Aspasia had over Pericles continues to be debated but his accomplishments are well-established. Pericles increased Athens' power through his use of the Delian League to form the Athenian empire and led his city through the First Peloponnesian War (460-446 BCE) and the first two years of the Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). He was still actively engaged in political life when he died during The Plague at Athens, 430-427 BCE, in 429 BCE.

Early Life & Rise to Power

Pericles was born in Athens, in 495 BCE, to an aristocratic family. His father, Xanthippus (l. c. 525-475 BCE) was a respected politician and war hero and his mother, Agariste, a member of the powerful and influential Alcmaeonidae family who encouraged the early development of Athenian democracy.

Pericles' family's nobility, prestige, and wealth allowed him to pursue his inclination toward education in any subject he fancied. He read widely, showing an especial interest in philosophy, and is recognized as the first Athenian politician to attribute importance to philosophy as a practical discipline which could help guide and direct one's thought and actions rather than a mere speculative past-time or the trade of the Sophists.

Pericles' early years were quiet and the introverted young man took to avoiding public appearances and speeches, instead preferring to devote his time to his studies. Later in life, this initial shyness would encourage the claims of his detractors that his consort Aspasia of Miletus taught him how to speak and wrote his speeches for him because, they said, there was no evidence of him learning oratory in his youth. It was a grave insult to a man of Athens, especially a statesman, to claim a woman was responsible for his successful career and Pericles' political enemies would focus on this charge repeatedly.

Pericles was involved in politics already in the early 460's BCE but precisely when is unknown. He prosecuted a case against his political rival Cimon (l. c. 510 - 450 BCE) in 463 BCE charging the latter with corruption in his dealings with Macedon. Cimon, son of Miltiades (the hero of Marathon, l. c. 555 - 489 BCE), was acquitted but this may have been due more to his political connections and influence than any failing on Pericles' part to prosecute the case.

Cimon was the leader of the conservative party and an able military commander who had fought at Salamis in 480 BCE when the Greeks defeated the Persians. During the Persian invasion of 480 BCE, Athens had rallied the other city-states to defense and, afterwards, assumed a dominant position. The Delian League, a confederation of the city-states, was formed in 478 BCE to provide defense against further Persian aggression and Cimon was instrumental in persuading various city-states to join.

Years before Pericles entered politics, Cimon was already influential and had done a great deal of good for the people of Athens and the other city-states. Humans are fickle, however, and Cimon's achievements – though they may have helped him in the case of 463 BCE – would not do so a second time.

The conservative party supported the aristocratic political assembly of the areopagus while the democratic faction in Athens encouraged reforms in the popular assembly known as ekklesia. The leader of the democratic party was Ephialtes (5th century BCE) who was Pericles' mentor. Cimon had served as a diplomat between Athens and Sparta a number of times since 478 BCE and, in 465 BCE, led the Athenian contingent of 4,000 soldiers to aid Sparta in putting down a rebellion by helots. Sparta insulted Athens by dismissing this sizeable force while welcoming the aid of other city-states. Athens responded by breaking their diplomatic ties with Sparta.

The reason for Sparta's dismissal of the Athenian force is unknown but it has been suggested that Sparta did not trust Athens to remain loyal and feared they would switch sides during the conflict. Early accounts simply state that the Spartans did not like the look of Cimon's soldiers.

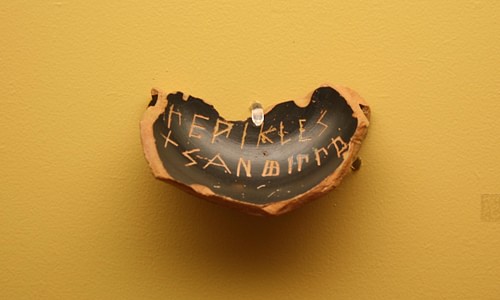

Whatever the reason was, in 461 BCE Pericles again charged Cimon with corruption – this time by claiming he was aiding Spartan interests – and succeeded in having his rival ostracized from the city for ten years. Shortly afterwards in the same year, Ephialtes was assassinated; these two events mark the beginning of Pericles' rise to power.

The First Peloponnesian War

The Delian League had existed for almost twenty years at this time and had increasingly become more of an extension of Athenian power and politics than a Greek confederacy for mutual defense. City-states preferred to simply pay Athens to defend them rather than send troops and supplies for the common cause and this penchant – which Athens welcomed - made the city rich and powerful.

Historian Edith Hamilton elaborates:

Back in 480, after the final defeat of the Persians, the Athenians had been chosen to lead the new confederacy of free Greek states. It was a lofty post and they were proud to hold it, but the role demanded a high degree of disinterestedness. Athens could be the leader of the free only if she considered the welfare of others on the same level with her own. During the war with Persia she had been able to do that…As head of the league, too, for a time she had not let her power corrupt her. But only for a short time. The temptation to acquire still more power proved as always irresistible. Very soon the free confederacy was being turned into the Athenian Empire. (117)

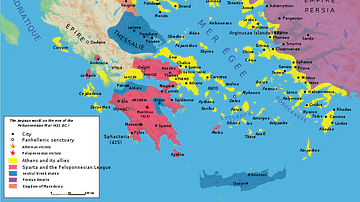

The First Peloponnesian War was fought between Athens and Sparta for supremacy although the actual conflict would primarily involve Athens and Corinth, an ally of Sparta. Greece was not a united country at this time but a confederacy of city-states bound together through “shared blood, shared language, shared religion, and shared customs” (Herodotus as cited in Boardman, 127). Certain city-states would align themselves with either Athens or Sparta, the two most powerful, depending on self-interest and this created the web of alliances which would form the opposing sides of the war.

Sparta feared that Athens' growing power was a threat but could not hope to defeat the Athenian navy which had only become larger and more effective since the victory at Salamis in 480 BCE. Corinth, however, had a fleet and so did another ally, Aegina, which the Spartan coalition made use of. Although these alliances – as well as the helot revolt and the Spartan insult to Athens - are commonly cited as the source of the conflict, Edith Hamilton expands on these claims:

The real cause of the war was not this or that trivial disturbance, the revolt of a distant colony, the breaking of an unimportant treaty, or the like. It was something far beneath the surface, deep down in human nature, and the cause of all the wars ever fought. The motive power was greed, that strange passion for power and possession which no power and no possession satisfy. Power, or its equivalent wealth, created the desire for more power, more wealth. The Athenians and the Spartans fought for one reason only – because they were powerful and therefore were compelled to seek more power. (114)

Pericles, as commander-in-chief, led the Athenian forces in a number of battles but neither side could gain a significant advantage. A truce was finally agreed to, orchestrated by Cimon, who returned from his exile in 451 BCE and served as intermediary on Pericles' behalf. The truce allowed Pericles to focus his attention on other areas. He issued his so-called Congress Decree in 449 BCE inviting all the city-states to gather for talks on a unified country but when Sparta refused to attend, the initiative stalled. Hostilities were not resumed, however, and the First Peloponnesian War concluded with a treaty which established limits to the reach of both Athens and Sparta.

Aspasia & the Funeral Oration

Throughout the war, Pericles was engaged in various cultural initiatives in Athens which brought him into regular contact with the leading intellectuals of the city. Among these was the foreign-born writer and teacher Aspasia of Miletus and, in 445 BCE, he divorced his wife (name unknown) and began (or continued) a romantic relationship with Aspasia. Aspasia's talent as a writer, and close association with Pericles, encouraged his enemies to claim she was the author of his greatest speeches but it seems clear he had a gift for oratory from a young age, long before he met her, as evidenced in speeches such as the one which exiled Cimon.

The most famous of these speeches is his Funeral Oration, given at the conclusion of the First Peloponnesian War. In this work, Pericles praises the soldiers who fell in battle, the bravery of their Athenian ancestors, the families who sacrificed loved ones for the city, and encourages survivors to honor the memory of the fallen. His primary focus, however, is the glory of Athens and how unique it is among all the other cities of the world. The speech, recorded by Thucydides, highlights how Athenian democracy encourages personal freedom and sets the city apart from the rest as an example to all:

Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favours the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if no social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition. The freedom which we enjoy in our government extends also to our ordinary life. There, far from exercising a jealous surveillance over each other, we do not feel called upon to be angry with our neighbor for doing what he likes, or even to indulge in those injurious looks which cannot fail to be offensive, although they inflict no positive penalty. But all this case in our private relations does not make us lawless as citizens. Against this fear is our chief safeguard, teaching us to obey the magistrates and the laws, particularly such as regard the protection of the injured, whether they are actually on the statute book, or belong to that code which, although unwritten, yet cannot be broken without acknowledged disgrace. (History, II.34-46)

Although certainly an idealized vision of Athens, Pericles' speech continues to resonate in its advocacy for a free and democratic state and the benefits such a system offers. Throughout the work, he emphasizes how the city has been able to achieve its greatness through the freedom of thought and expression of the people. Although democracy was developing in Athens long before Pericles, his initiatives allowed it to flourish and, as it did, so did Athenian culture.

Cultural Achievements

During the Age of Pericles, Athens blossomed as a center of education, art, culture, and democracy. Artists and sculptors, playwrights and poets, architects and philosophers all found Athens an exciting and enlivening atmosphere for their work. Athens under Pericles saw the rebuilding and expansion of the agora and construction of the temples of the Acropolis including the glory of the Parthenon, begun in 447 BCE. The painter Polygnotus (l. 5th century BCE) created his famous works which were later immortalized by the writer Pausanias (l. c. 110 - 180 CE).

Playwrights Aeschylus (l. c. 525 - c. 456 BCE), Sophocles (l. c. 496 - c. 406 BCE), Euripides (l. c. 484 - 407 BCE), and Aristophanes (l. c. 460 - c. 380 BCE) - in short, all of the great Greek writers for the stage - invented theater as it is now known during this period. Hippocrates (l. c. 460 - c. 370 BCE), who inspired the Hippocratic Oath still taken by physicians today, practiced medicine at Athens while Herodotus (l. c. 484 - 425/413 BCE), the Father of History, traveled and wrote his famous work.

Great sculptors like Phidias (l. c. 480 - c. 430 BCE), who created the statue of Zeus at Olympia (considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World), as well as the statue of Athena Parthenos for the Parthenon worked at his craft and Myron (l. c. 480 - c. 440 BCE) the sculptor produced his masterpiece known as the Discus Thrower.

The great philosophers Protagoras (l. c. 485 - c. 415 BCE) Zeno of Elea (l. c. 465 BCE), and Anaxagoras (l. c. 500 - c. 428 BCE) were all personal friends of Pericles. Anaxagoras, in fact, is said to have influenced Pericles' public demeanor and acceptance of fate, especially after the death of Pericles' sons from plague. Socrates (l. c. 470/469 - 399 BCE), the founder of western philosophy, also lived and taught in Athens during this period and his students – most notably Plato (l. 428/427 - 348/347 BCE) – would go on to found their own philosophical schools and change western thought forever.

The Second Peloponnesian War & Death

The Age of Pericles, however, could not last any more than any other in history. At the beginning of 431 BCE Athens entered into the Second Peloponnesian War with Sparta which would end in Athens' defeat; but Pericles would not live to see the fall of his city. In his Funeral Oration, Pericles said that, “Grief is felt not so much for the want of what we have never known as for the loss of that to which we have been long accustomed” (History, II.43). The Athenians present at the speech would certainly have keenly felt this particular line in reference to those they had lost but, by the end of the second war with Sparta, his words would no doubt have resonated even more as Athens lost everything it had worked so hard for.

Soon after the war began, the great leader who had directed the city through the first conflict died in 429 BCE; the plague struck the city and Pericles was among its victims. Bereft of his leadership, the Athenians made mistake after mistake in their military decisions leading eventually to their defeat by the Spartans in 404 BCE, the destruction of their city's walls, and their occupation and rule by Sparta.

In his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides makes clear what a disaster Pericles' death was for Athens in that those who came after him desired to be popular rather than effective and, in so doing, doomed the city to ruin:

The reason [Pericles was such a superior statesman was that he was] strong in both repute and intellect and was conspicuously incorruptible, held the masses on a light rein, and led them rather than let them lead him. This was because he did not have to adapt what he said in order to please his hearers, in an attempt to gain power by improper means, but his standing allowed him even to speak against them and provoke their anger. Whenever he saw that they were arrogant and undeservedly confident, he would speak to strike terror into them; and when he saw them unreasonably afraid he would restore their confidence once more. The result was in theory democracy but in fact rule by the first man. (II. 64-65)

His successors never lived up to Pericles' ideal leadership and Athens suffered accordingly. Although Thucydides admired and supported Pericles, there is no reason to conclude that his claims are simply a form of bias. History bears out Thucydides' view in that, with the death of Pericles, Athens fell into an intellectual, cultural, and spiritual darkness which the Athenians would struggle with over the next 30 years, culminating in the execution of Socrates in 399 BCE.

Although Pericles has been criticized as a “populist” who appealed to the baser instincts of the people, as well as a war-monger who encouraged both wars with Sparta, he quite obviously was able to create an atmosphere of freedom of thought and expression which resulted in some of the greatest contributions to world culture ever made.

The period of Greek history in which he lived and reigned is rightly known as the Age of Pericles because his initiatives allowed that era to flourish. Even at war, Pericles was able to maintain the social stability necessary for art, literature, and philosophy to flourish and the works of this age continue to influence and inspire people around the world in the present day.