Located on the fertile Mesara plain in central Crete, Phaistos has been inhabited since the Final Neolithic period (c. 3600-3000 BCE). The settlements greatest period of influence was from the 20th to 15th century BCE, during which time it was, along with Knossos, Malia and Zakros, one of the most important centres of the Minoan civilization.

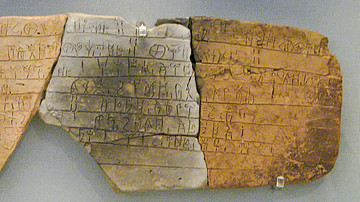

The settlement of Phaistos continued into the Mycenaean era and this period was followed by a brief resurgence in the 7th century BCE. Phaistos' independence was finally lost when it was conquered in c. 180 BCE by Gortyn, the Roman capital of Crete. Artefacts from the site include many Linear A tablets, seals, and the celebrated but mysterious Phaistos disk, a clay disc covered in undeciphered symbols.

Origin of the Name

Tradition attributes the founding of Phaistos to either Minos, ruler of Knossos, or to his brother Radhamanthys. The name derives from Phaistos (the son or grandson of Herakles), who was killed by the Cretan King Idomeneus. It was Idomeneus who led the Cretans in the Trojan War and Phaistos is described in Homer's Iliad as 'a well-founded city'.

Architecture

The first large scale buildings date back to c. 3000 BCE but it was from 2000 BCE that the first palaces were built on the site. The first and finest palace was constructed between 2000 BCE and 1700 BCE. This large scale Minoan palace was built on a wide plateau on the lowest of three hills, 97m high. The palace, at its widest extent, occupied an area of 8,400 square metres and was second only to Knossos in size and importance. Constructed on three terraces and ranging from one to three stories, it was a splendid building, with the large courts (the biggest being 1,100 square metres), royal apartments, colonnades, stairways and light wells so typical of Minoan palatial architecture.

It has been suggested that the palace was an administrative, manufacturing, and commercial centre with storage of goods for domestic and foreign trade and shrines for religious worship - in particular, of the Mother Goddess. Some scholars argue that the thousands of sealings, Linear A tablets and the quality and variety of ceramics found - particularly, Kamares ware - would suggest that the palace was something more than a communal gathering place and was perhaps the seat of a theocratic power. However, the archaeological evidence is inconclusive as to the specific role of the palace in the community. Certainly, the splendour of the buildings and richness of pottery finds suggest a period of great affluence for the city as part of the wider network of sites on Minoan Crete.

The first palace complex was destroyed by two earthquakes around 1700 BCE and the second palace was soon built over the first. More modest than its predecessor, the second palace was itself destroyed mid-1600 BCE and abandoned until a brief revival in the 16th century BCE, after which Phaistos became second in importance to nearby Hagia Triada, the local seat of power under the Mycenaeans.

Archaeological Finds

Excavations of the site were begun in the early 20th century by the Italian Archaeological School and continue to the present day. The extensive remains visible today are principally from the second palace. There are two large staircases - the monumental entrance to the main court (14m wide) and the entrance to the west court, (6m in height); a large theatre area with nine ranks of stone seats or steps, 24m long and with a possible capacity of over 400 standing spectators; the western court, where the celebrated bull-games were possibly held; two walled, circular pits; a lobby with benches; magazine rooms; remains of light wells; and large apartments, one - the so-called King's Megaron - still with original alabaster flagstones and red plaster interstices.

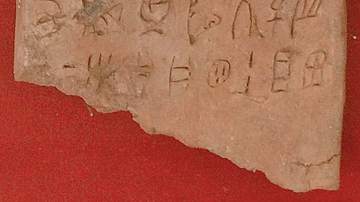

Amongst the many artefacts found at the site, the most celebrated is the unique Phaistos Disk. This clay disk, dated to 1600 BCE, is imprinted on both sides with 241 symbols or Cretan hieroglyphics in a spiral pattern. The disk may be said to be an ancestor of typography as each symbol was separately printed using a stamp. Despite much scholarly endeavour and debate, these symbols remain undeciphered. Artefacts from Phaistos now reside primarily in the Archaeological Museum of Iraklion, Crete.