The cascading geothermal pink and white terraces of Aotearoa New Zealand were often referred to internationally and within New Zealand as the eighth wonder of the world. They were a famous tourist attraction in the 19th century until the terraces were destroyed by the volcanic eruption of Mount Tarawera on 10 June 1886. The terraces were regarded by Māori as a taonga (a treasure).

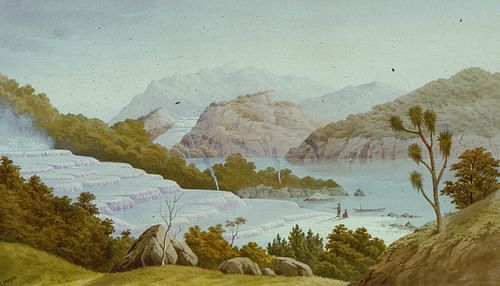

Located on the shores of Lake Rotomahana, 20 kilometres (12.4 mi) southeast of Rotorua on the North Island, the pink and white terraces were formed by silica-rich waters that flowed from boiling geysers, tumbling down the hillside, creating crystallised terraces, bathing pools, and natural staircases that were estimated to be over 1,000 years old.

The fan-shaped white terrace or Te Tarata ('the tattoed rock') was the larger formation, spanning approximately eight hectares (20 ac). Te Tarata's height was 30 metres (98 ft), and it had 50 scalloped layers or terraces of crystallised silica deposits. It was located at the northeast end of Lake Rotomahana, approximately 1.5 kilometres (0.9 mi) from the pink terrace.

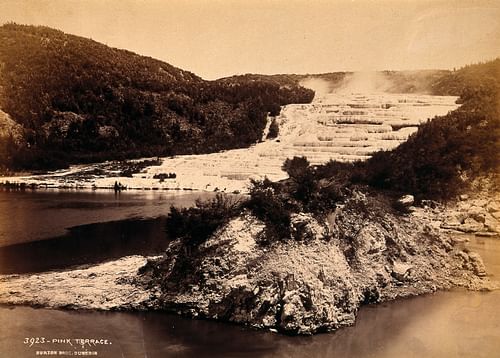

The pink terrace or Te Otukapuarangi ('the fountain of the clouded sky') was lower and on the western side of Lake Rotomahana. Otukapuarangi's geothermal waters were enjoyed by visitors, who bathed in the upper terrace blue water pools for health benefits. The salmon-pink appearance of this terrace, which rose to a delicate pink flush at the summit, was likely due to trace elements such as iron and manganese that dissolved in the hot springs.

The local Te Arawa iwi (tribe), who had ancestral rights to Lake Rotomahana, considered the white terrace to be male and the pink terrace to be female.

Although New Zealand's natural wonder was presumably destroyed, a rich visual history remains, and there are claims that the remnants of the terraces have been recently rediscovered.

Early European Visitors

The pink and white terraces lay at the foot of Mount Tarawera on the volcanic plateau of the North Island (known as the Ōkataina Volcanic Centre). Tarawera itself was tapu (taboo), for its slopes were the final resting ground of the local iwi's tapuna (ancestors), and pakeha (Europeans) could not step foot on it. However, early visitors to the terraces could stay with missionaries in the area before commercial hotels were built in the 1870s.

New Zealand, at the time, was a remote colony within the British Empire. The Victorian world discovered the terraces when Sir George Grey (1812-1898), a British soldier and twice governor of New Zealand, visited them in 1849 and spread the word of their spectacular beauty. The Victorian tourist, after a sea voyage to New Zealand of up to six months, then travelled 200 kilometres (124 mi) by steam train from Auckland to Tauranga, followed by a bumpy coach service to Rotorua. From there, it was another horse-drawn journey through uncultivated country to Te Wairoa, the gateway to the terraces, where the steam from boiling geysers could be seen rising above the surrounding Tikitapu bush and tall tree ferns. Accommodation was provided by the Rotomahana Hotel, owned by Joseph McRae (1849-1938), who survived the Tarawera eruption. A two-hour canoe journey to the terraces with local Māori guides would be arranged in the evening for the following day.

One of the earliest European visitors to the terraces was the German naturalist Ernst Dieffenbach (1811-1855), who lived and worked in New Zealand. In June 1841, Dieffenbach, who was the first European to scale Mount Taranaki successfully, was surveying for the New Zealand Company. His book, Travels in New Zealand, published in 1843, described the vivid blue waters of the bathing pools against the crystalline whiteness of the terraces, which helped spark the arrival of tourists. Travellers to the terraces were those who could afford the extensive journey or were officers of the British forces in New Zealand.

The Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) bathed in a cupped pool on the pink terraces in 1874 and said:

You go from one bath to another, trying the warmth of each. The water trickles from the one above to the one below, coming from the vast boiling pool at the top, and the lower, therefore, are less hot than the higher. The baths are shell-like in shape, like vast open shells, the walls of which are concave and the lips ornamented in a thousand forms. Four or five may sport in one of them, each without feeling the presence of the other. I have never heard of other bathing like this in the world. (quoted in Conly, 5).

Queen Victoria's son, Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh (1844-1900), left his mark behind in 1870 when he scrawled his name on a terrace wall. It became the habit of visitors to either graffiti the terraces or take away a souvenir such as native feathers and flowers encrusted with silica.

Fortunately, a rich legacy of artwork recorded the visual landscape of the pink and white terraces before their destruction. The English-born artist, Charles Blomfield (1848-1926) – known as the artist of the terraces - and his daughter, Mary, camped and painted for six weeks in 1885, even boiling a plum pudding tied on a long string and dunking it into the hot springs. John Hoyte (1835-1913), who arrived in New Zealand from London in 1860, also painted the terraces, depicting them in a soft, golden glow. Photographers found the terraces an attractive subject and flocked to the area, carrying the cumbersome equipment of plate photography. The Burton Brothers, a photographic studio based in Dunedin, produced albumen prints of the terraces.

Even a former New Zealand premier and close friend of the poet Robert Browning (1812-1889), Alfred Domett (1811-1887), was inspired to write that each scalloped terrace brimmed "with water – brilliant, yet in hue/ the tenderest delicate harebell blue/ deepening to violet" (A New Zealand Verse, 42)

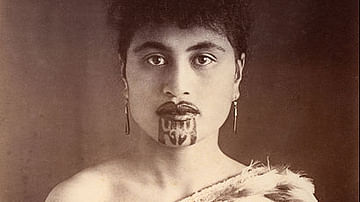

Māori Guides & Ghostly Warnings

Sophia Hinerangi (c. 1834-1911) and Keita Rangitūkia Middlemass (fl. 1880s-1918) were two popular Māori guides, known respectively as Guide Sophia and Guide Kate. Hinerangi means 'young girl in heaven', and Guide Sophia's father was Alexander Grey (1796-1839), a Scot, and her mother was of the Ngāpuhi iwi. Both guides spoke fluent English and accompanied tourists to the terraces. It was a lucrative tourism business with estimates of £4,000 a year in income for local iwi.

Guide Sophia was not only a popular guide but was one of the first to notice warning signs before the eruption of Mount Tarawera – signs that were largely ignored. The story of the phantom canoe might have passed into the realm of Māori mythology had it not been for independent pakeha witnesses. On 31 May 1886 – eleven days before the disaster – Guide Sophia was out on Lake Rotomahana with a group of six tourists when the lake level suddenly fell and then rose. This was followed by a phantom double-hulled waka (war canoe) speeding silently across the lake with a crew of 13 Māori standing in flax robes, their heads bowed. For the Māori onlookers, including Guide Sophia, the meaning was crystal clear: it was a waka wairua or spirit canoe, ferrying the souls of the departed to Mount Tarawera, where ancestors were buried.

In the canoe with Guide Sophia were three other Māori women, Father Kelliher, a priest from Auckland, Dr T. S. Ralph from Australia, Mr and Mrs Sise from Dunedin, and William Quick, who confirmed they had seen the canoe, which vanished before their eyes.

Guide Sophia also found the Te Wairoa creek had dried up at the landing point of Waituhurihuri, and canoes were stuck in cracked mud. Over the 1885-1886 season, the flax did not flower, which was interpreted as meaning a long hot summer was ahead, accompanied by a great earthquake in 1886.

A final unsettling sign was the collection of honey pollinated by wild bees on Mount Tarawera. It was considered tapu honey, and Guide Sophia refused to eat it when it was offered to her. It is said that everyone who ate the tapu honey perished in the volcanic eruption. Guide Sophia survived.

The last person to see the pink and white terraces was the Englishman Edwin Armstrong Bainbridge (1866-1886), a 20-year-old on a grand tour of the Pacific. The heir of Eschott Hall, Felton, Northumberland, Bainbridge and two other Englishmen had been taken by Guide Sophia to see the terraces on the afternoon before Mount Tarawera erupted. The hotelier, Joseph McRae, then arranged for Bainbridge to go pheasant shooting, but by the evening of 9 June 1886, Bainbridge was certain it was to be his last night on Earth.

The Night Mount Tarawera Erupted

In the early hours of the morning, Thursday, 10 June 1886, Mount Tarawera erupted. The evening before, the inhabitants of Te Wairoa had passed the time watching the conjunction of Mars with the Moon, which happened at 10:20 p.m. At 12:30 a.m., the first earthquake was felt. Joseph McRae was getting ready for bed after a long night and was rattled by the quake. Hotel crockery smashed to the floor of his hotel, but McRae retired, earthquakes being a common occurrence in New Zealand.

A loud roar was then heard at around 2:15 a.m. as Mount Tarawera split open, throwing scoria and ash into a sky flashing with forked lightning. An ink-black eruption cloud lit by electrical charges and reaching 9.5 kilometres (5.9 mi) was seen as the ground shook violently and hurricane-level winds blew. Aucklanders thought the booming sound was a distress signal from a vessel in distress off Takapuna or a Russian warship. Fire alarm bells in the Dunedin fire station, 925 kilometres (574 mi) to the south of Te Wairoa, rang intermittently for a few hours.

Volcanic ash and mud covered an estimated area of 15,000 square kilometres (5791 sq mi). More than 150 people were killed, some buried alive in their houses to a depth of 1.5 metres (4.9 ft), and Te Wairoa was destroyed. More than 60 people sheltered at Guide Sophia's whare (hut), 150 metres (492 ft) from the Rotomahana Hotel, while others took refuge in a chicken house. Joseph McCrae's hotel collapsed under a hail of red-hot volcanic rock. As the eruption was happening, the young tourist Edwin Bainbridge, who was staying at McCrae's and was killed when a balcony of the hotel collapsed, managed to write his final words:

This is the most awful moment of my life. I cannot tell when I may be called upon to meet my God. I am thankful that I find His strength sufficient for me. We are under heavy falls of volcanoes ... (quoted in Conly, 40).

The schoolmaster Charles Haszard (1839-1886) and his family had been celebrating his wife Amelia's birthday the night before the eruption. Charles Haszard and three of his children were buried when the roof of their house collapsed as lava rained down. Ina Haszard (c. 1870-1953), one of the daughters, and Amelia Haszard survived, and Ina would later produce a visual record of her experience. Her 1935 painting Mt Tarawera in Eruption – part of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa's collection – is based on her memory of the event that happened almost half a century before.

New Zealand's Pompeii

The eruption lasted for six hours. Survivors were making their way to Rotorua as a search party was sent out. The postmaster, Captain Roger Delamere Dansey, was on duty in Rotorua at the time of the Tarawera eruption and stayed at his post to tap out to the world that Mount Tarawera had erupted.

The first rescuer to reach Te Wairoa arrived with casks of water on Friday, 11 June 1886, the dust and ash blinding both himself and his horse. Over the next few weeks, it became apparent that Lake Rotomahana had completely disappeared, leaving behind steaming holes and hot mud, the hillsides were covered in ash, and the pink and white terraces were thought to have been destroyed.

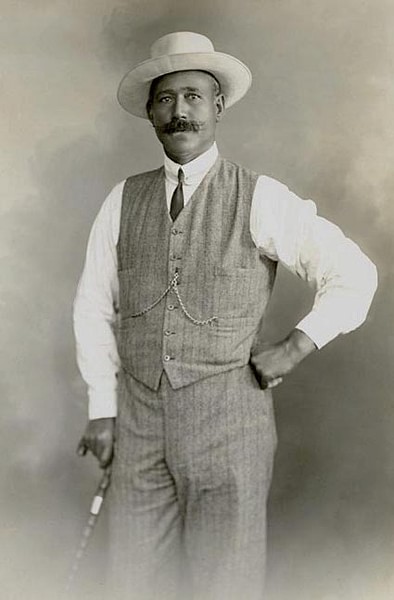

A prominent person involved in the rescue operations was Alfred Patchet Warbrick (1860-1940). The son of an English immigrant and Māori mother, Warbrick was a well-known rugby player and boatbuilder. Warbrick, who identified with the Ngāti Rangitihi iwi, witnessed the eruption from a bush hut on Makatiti hill, north of Lake Tarawera. On 14 June, Warbrick led a party of nine to discover what had happened to the inhabitants of the small Māori kainga (settlement) of Moura on the headland of Lake Tarawera. The kainga had been completely buried, and there were no survivors. Ironically, Warbrick's brother, Joseph Warbrick (1862-1903), who assisted Alfred in rescue efforts and was also a rugby player and tour guide, died when the Waimangu geyser in Rotorua erupted unexpectedly in 1903.

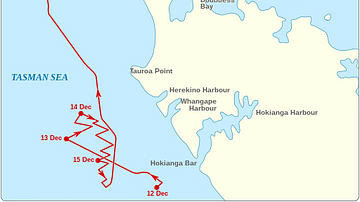

Alfred Warbrick was also tasked with trying to find out what had happened to the terraces, and along with special correspondent J. A. Philp from the Auckland Evening Star, he explored one of the sulphur-filled craters that had once been Lake Rotomahana. Warbrick reported that he believed he could see the pink terrace buried under mud, but the conditions were too dangerous to explore further. Alfred Warbrick never accepted that the pink and white terraces had been destroyed despite Assistant Surveyor-General Stephenson Percy Smith (1840-1922), who had been sent by the government to provide scientific evidence for the disaster, declaring they were gone forever.

The village of Te Wairoa was declared tapu because some bodies had not been recovered or were discovered in a good state of preservation. A Māori woman's body, with a young girl across her knees, was found in a seated position, a Bible in a shawl wrapped around her.

One of the tour guides who worked on the terraces provided an eyewitness account to a radio station on the 68th anniversary of the eruption in 1954, which captured the terror of that night.

The Terraces Rediscovered

The buried village of Te Wairoa has become a tourist attraction, but what has always been uncertain is whether the terraces were buried by mud and debris or completely destroyed. In 2011, two automated underwater vehicles from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) located what scientists believed to be remnants of the pink terrace at a depth of 68 metres (223 ft). A detailed view of the lake floor topography showed the post-eruption lake floor – a free map is available.

Part of the problem has been that the exact location of the pink and white terraces is not known. The only survey of the terraces before the eruption was in 1859 when Christian Gottlieb Ferdinand von Hochstetter (1829-1884) arrived in New Zealand as the geologist for an Austrian global scientific expedition. Hochstetter's field diary and his survey of the Lake Rotomahana region, which was completely altered by Mount Tarawera's eruption that dramatically expanded the lake's size and depth, were discovered in the Hochstetter family library in Switzerland in 2010. This is significant because Hochstetter's survey contained compass bearings that could be used to find the terraces. Researchers reverse-engineered Hochstetter's work six years after the WHOI underwater data collection and believe they established where Hochstetter would have been standing in 1859 to undertake the survey. The conclusion was that the terraces did not sink to the bottom of Lake Rotomahana but remained buried at a depth of around 15 metres (49 ft).

WHOI scientists reaffirmed their findings in 2018, but any extensive investigation requires the permission of local iwi who own the ancestral lands where the pink and white terraces once stood. So, for the moment, the iconic historic and cultural site of New Zealand, although thought to have been found, remains lost.