In 1533 CE the Inca Empire was the largest in the world. It extended across western South America from Quito in the north to Santiago in the south. However, the lack of integration of conquered peoples into that empire, combined with a civil war to claim the Inca throne and a devastating epidemic of European-brought diseases, meant that the Incas were ripe for the taking. Francisco Pizarro arrived in Peru with an astonishingly small force of men whose only interest was treasure. With superior weapons and tactics, and valuable assistance from locals keen to rebel, the Spanish swept away the Incas in little more than a generation. The arrival of the visitors to the New World and consequent collapse of the Inca Empire was the greatest humanitarian disaster to ever befall the Americas.

The Inca Empire

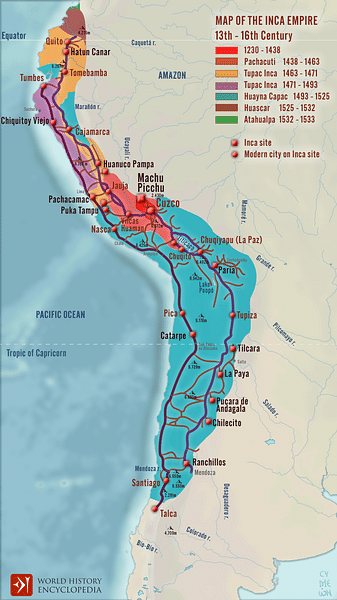

The Incas themselves called their empire Tawantinsuyo (or Tahuantinsuyu) meaning 'Land of the Four Quarters' or 'The Four Parts Together'. Cuzco, the capital, was considered the navel of the world, and radiating out were highways and sacred sighting lines (ceques) to each quarter: Chinchaysuyu (north), Antisuyu (east), Collasuyu (south), and Cuntisuyu (west). Spreading across ancient Ecuador, Peru, northern Chile, Bolivia, upland Argentina, and southern Colombia and stretching 5,500 km (3,400 miles) north to south, a mere 40,000 Incas governed a huge territory with some 10 million subjects speaking over 30 different languages.

The Incas believed they had a divine right to rule over conquered peoples as in their mythology they were brought into existence at Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) by the sun god Inti. As a consequence, they regarded themselves as the chosen few, the 'Children of the Sun', and the Inca ruler was Inti's representative and embodiment on earth. In practical terms, this meant that all speakers of the Inca language Quechua (or Runasimi) were given privileged status, and this noble class then dominated all the important political, religious, and administrative roles within the empire.

The rise of the Inca Empire had been spectacularly quick. Although Cuzco had become a significant centre some time at the beginning of the Late Intermediate Period (1000-1400 CE), the process of regional unification only began from the late 14th century CE and significant conquest in the 15th century CE. The Empire was still young when it was to meet its greatest challenge.

Pizarro & the Conquistadores

Francisco Pizarro and his partner Diego de Almagro were both in their mid-50s, from humble backgrounds, and neither had won any renown in their native Spain. Adventurers and treasure-seekers, they led a small group of Spanish adventurers eager to find the golden treasures their compatriots had found in the Aztec world of Mexico a decade earlier. Sailing down the Pacific coast from Panama in two small caravel merchant ships, they searched on in Colombia and the Ecuadorian coast but could not find the gold they so desperately sought. This was Pizarro's third such expedition, and it seemed his very last chance for fame and glory.

Then, in 1528 CE, one Bartolomé Ruiz (the expedition's pilot) captured a raft off the coast which was full of treasure. There might, after all, be something worth exploring deeper in South America. Pizarro used the discovery as a means to secure the right from the Spanish king Charles V to be governor of any new territory discovered with the Crown getting its usual one-fifth of any treasure found. With a force of 168 men, which included 138 veterans, 27 cavalry horses, artillery, and one friar, a Father Valverde, Pizarro headed for the Andes.

In 1531 CE, making slow and careful progress, he reached and conquered Coaque on the Ecuadorian coast and waited for reinforcements. These arrived the following year and swelled the Spanish force to 260 men of which 62 were cavalry. The force moved on down the coast to Tumbes, pillaging as they went and putting the natives to the sword. Moving on again they began to see the tell-tale signs of a prosperous civilization – storehouses and well-built roads. They formed a new settlement at San Miguel (modern Piura), and by the end of the year 1532 CE Pizarro was ready to make first contact with the rulers of what seemed a huge and wealthy empire.

Trouble in the Empire

When the foreign invaders arrived in Peru the Incas were already beset by some serious internal problems. As we have seen, their massive empire was a politically fragile and loose integration of conquered states whose subservience came from Inca military dominance and the taking of hostages - both of important persons and important religious artefacts - to ensure a continued, if uneasy, compliance to Cuzco's rule. Unpopular taxes were extracted in the form of goods or service (military and general labour), and many communities were forcibly resettled to other parts of the empire or had to welcome new communities of people more loyal to their overlords.

The Incas also imposed their religion on conquered peoples, even if they allowed the continued worship of some gods provided they were given a lesser status to Inti. The Incas even imposed their own art across the empire as a way to visually impress exactly who was the ruling class. There were some benefits to Inca rule – a more regulated food supply, better roads and communications, the possibility of Inca military protection, and occasional state-sponsored feasts. All in all, though, the lot of a conquered area was such that, in many cases, when a rival power threatened Inca rule, loyalty to preserve the empire was somewhat lacking. Some areas, especially in the northern territories were constantly in rebellion, and an ongoing war in Ecuador necessitated the establishment of a second Inca capital at Quito.

Perhaps more significantly than this unrest, when Pizarro arrived on the scene the Incas were fighting amongst themselves. On the death of the Inca ruler Wayna Qhapaq in 1528 CE, two of his sons, Waskar and Atahualpa, battled in a damaging six-year civil war for control of their father's empire. Atahualpa finally won but the empire was still beset by factions yet to be fully reconciled to his victory.

Finally, if all those factors were not enough to give the Spanish a serious advantage, the Incas were at that time hit by an epidemic of European diseases, such as smallpox, which had spread from central America even faster than the European invaders themselves. Such a disease killed Wayna Qhapaq in 1528 CE and in some places a staggering 65-90% of the population would die from this invisible enemy.

Pizarro Meets Atahualpa

On Friday, 15th of November, 1532 CE, the Spaniards approached the Inca town of Cajamarca in the highlands of Peru. Pizarro sent word that he wished to meet the Inca king, there enjoying the local springs and basking in his recent victory over Waskar. Atahualpa agreed to finally meet the much-rumoured bearded white men who were known to have been fighting their way from the coast for some time. Confidently surrounded by his 80,000 strong army Atahualpa seems not to have seen any threat from such a small enemy force, and he made Pizarro wait until the next day.

The first formal meeting between Pizarro and Atahualpa involved a few speeches, a drink together while they watched some Spanish horsemanship, and not much else. Both sides went away planning to capture or kill the other party at the first available opportunity. The very next day Pizarro, using the conveniently labyrinth-like architecture of the Inca town to his advantage, set his men in ambush to await Atahualpa's arrival in the main square. When the royal troop arrived, Pizarro fired his small canons, and then his men, wearing armour, attacked on horseback. In the ensuing battle, where firearms were mismatched against spears, arrows, slings, and clubs, 7,000 Incas were killed against zero Spanish losses. Atahualpa was hit a blow on the head and captured alive.

Atahualpa's Ransom & Death

Either held for ransom by Pizarro or even offering a ransom himself, Atahualpa's safe return to his people was promised if a room measuring 6.2 x 4.8 metres were filled with all the treasures the Incas could provide up to a height of 2.5 m. This was done, and the chamber was piled high with gold objects from jewellery to idols. The room was then filled twice again with silver objects. The whole task took eight months, and the value today of the accumulated treasures would have been well over $300 million. Meanwhile, Atahualpa continued to run his empire from captivity, and Pizarro sent exploratory expeditions to Cuzco and Pachacamac while he awaited reinforcements from Panama, enticed by sending a quantity of gold to hint at the wealth on offer. Then, having got his ransom, Pizarro summarily tried and executed Atahualpa anyway, on the 26th of July, 1533 CE. The Inca king was originally sentenced to death by burning at the stake, but after the monarch agreed to be baptised, this was commuted to death by strangulation.

Some of Pizarro's men thought this was the worst possible response, and Pizarro received criticism from the Spanish king for treating a foreign sovereign so shabbily, but the wily Spanish leader had seen just how subservient the Incas were to their king, even when he was held captive by the enemy. As a living god, Pizarro perhaps knew that only the king's death could bring about the total defeat of the Incas. Indeed, even in death, the Inca king exerted an influence over his people for the severed head of Atahualpa gave birth to the enduring Inkarri legend. For the Incas believed that one day the head would grow a new body and their ruler would return, defeat the Spanish, and restore the natural order of things. Crucially, the period of Atahualpa's captivity had shown the Spanish that there were deep factions in the Inca Empire and these could be exploited to their own advantage.

The Fall of Cuzco

Having cut off the snake's head, the Spanish then set about conquering Cuzco with its vast golden treasures which were reported by Hernando Pizarro following his reconnaissance expedition there. After that, they could deal with the rest of the empire. The first battle was with troops loyal to Atahualpa near Hatun Xauxa, but the Spaniards were helped by the local population delighted to see the back of the Incas. The Spaniards were given supplies from the local Inca storehouses, and Pizarro established his new capital there. Local assistance and the plundering of the Inca storehouses would become a familiar pattern which aided Pizarro for the remainder of his conquest.

The invaders next defeated an army in retreat at Vilcaswaman but did not have everything their own way and even suffered a military defeat when an advance force was attacked by surprise on their way to Cuzco. The next day the Old World visitors resumed their unstoppable march, though, and swept all before them. A brief resistance at Cuzco was overcome, and the city fell into Pizarro's hands with a whimper on 15th of November, 1533 CE. The treasures of the city and the golden wonders of the Coricancha temple were ruthlessly stripped and melted down.

Pizarro's first attempt to install a puppet ruler - Thupa Wallpa, the younger brother of Waskar - failed to restore any sort of political order, and he soon died of illness. A second puppet ruler was installed – Manco Inca, another son of Wayna Qhapaq. While he ensured the state did not collapse from within, Pizarro and his men left to pacify the rest of the empire and see what other treasures they could find.

Conquering the Empire

The Spanish were severely tested in the northern territories, where armies led by Ruminawi and Quizquiz held out, but these too capitulated from internal strife and their leaders were killed. The Europeans' relentless conquest could not be answered. In this, they were greatly helped by the Inca mode of warfare which was highly ritualised. Such tactics as deceit, ambush, and subterfuge were unknown to them in warfare, as were changing tactics mid-battle and seizing opportunities of weakness in the enemy as they arose. In addition, Inca warriors were highly dependent on their officers, and if these conspicuous individuals fell in battle, a whole army could quickly collapse in panicked retreat. These factors and the superior weaponry of the Europeans meant the Incas had very little chance of defending a huge empire already difficult to manage. The Incas did quickly learn to fight back and deal with cavalry, for example by flooding areas under attack or fighting on rough terrain, but their spears, slings, and clubs could not match bullets, crossbows, swords, and steel armour. The Spaniards also had nearly half the population of the old empire fighting for them as old rivalries and factions re-emerged.

The Spanish soon found out that the vast geographical spread of their new empire and its inherent difficulties in communication and control (even if their predecessors had built an excellent road system) meant that they faced the same management problems as the Incas. Rebellions and defections spread all over, and even Manco Inca rebelled and formed his own army to try and win real power for himself. Cuzco and the new Spanish stronghold of Cuidad de Los Reyes (Lima) were besieged by two huge Inca armies, but the Spaniards held out until the attackers had to retreat. The Inca armies were largely composed of farmers, and they could not abandon their harvest without starving their communities. The siege was raised again the next year, but once more the Spanish resisted, and when they killed the army leaders in a deliberately targeted attack, resistance to the new order ebbed away. Manco Inca was forced to flee south where he set up an Inca enclave at Vilcabamba. He and his successors would resist for another four decades. Finally, in 1572 CE, a Spanish force led by Viceroy Toledo captured the Inca king Thupa Amaru, took him back to Cuzco, and executed him. The last Inca ruler was gone and with him any hope of restoring their once-great empire.

Conclusion

Atahualpa, following victory in the war with his brother, had killed historians and destroyed the Inca quipu records in what was intended to be a total renewal, what the Incas called a pachakuti or 'turning over of time and space', an epoch-changing event which the Incas believed periodically occurred through the ages. How ironic then, that Atahualpa was to suffer a pachakuti himself and the new rulers would similarly loot, burn, and destroy every vestige of Andean culture they could find. The arrival of the Old World into the New turned it upside down. Nothing would ever be the same again.

The Spanish, after decades of their own internal problems, which included the murder of Pizarro, eventually established a stable colonial government in 1554 CE. For the Andean people, their way of life, which had stretched back millennia despite the Inca interruption, would be challenged again by the new epoch. These were the lucky ones, though, as by 1570 CE 50% of the pre-Columbian Andean population had been wiped out. For those ordinary people who survived the ravages of war and disease, there was to be no respite from a rapacious overlord once again eager to steal their wealth and impose on them a foreign religion.