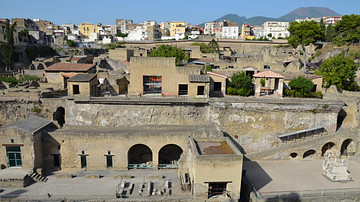

Pompeii was a large Roman town in Campania, Italy which was buried in volcanic ash following the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE. Excavated in the 19th-20th century, its excellent state of preservation gives an invaluable insight into Roman everyday life. Pompeii is perhaps the richest archaeological site in the world for the volume of data available to scholars.

Settlement in Campania

The area was originally settled in the Bronze Age on an escarpment on the mouth of the river Sarno. The site of Pompeii and the surrounding area offered the twin advantages of a favourable climate and rich volcanic soil which allowed for the blossoming of agricultural activity, particularly olives and grapes. Little did the original settlers realise that the very escarpment on which they built had been formed by a long-forgotten eruption of the now seemingly innocent mountain that over-shadowed their town. However, in Greek mythology, a hint at the volcano's power was found in the legend that Hercules had here fought giants in a fiery landscape. Indeed, the nearby town Herculaneum, which would suffer the same fate as Pompeii, was named after this heroic episode. In addition, Servius informs us that the name Pompeii derives from pumpe, which was the commemorative procession in honour of Hercules' victory over the giants.

Greeks established colonies in Campania in the 8th century BCE and the Etruscans were also present until they were defeated by Syracusan and local Greeks at the battle of Cumae in 474 BCE. From then on the Samnite people from the local mountains began to infiltrate and dominate the region. The 4th century BCE saw Samnite infighting break out into the Samnite Wars (343-290 BCE) across Campania and the beginning of Roman influence in the region. Pompeii was favoured by Rome and the town flourished with large building projects being carried out in the 2nd century BCE. However, Pompeii, with its Samnite origins, had always been independently minded when it came to Roman authority and Sulla besieged the city following a rebellion and set up his colony of Venus in 80 BCE, re-settling 4-5,000 legionaries in the town. Another period of prosperity followed, a local senate (ordo decurionum) was formed and a new amphitheatre and odeion were built with capacity for 5000 and 1500 spectators respectively. After centuries of ups and downs, the town had reached its peak.

Following seismic activity and coastal changes, the ancient city now stands 2km inland but it would have been much closer to the sea and the mouth of the Sarno in Roman times and around four metres lower. The Roman town of Pompeii covers some three square kilometres (one third remains unexcavated) but the outer suburbs were also densely populated. There were also hundreds of farms and around one hundred villas in the surrounding countryside. The population of the town has been estimated at 10-12,000, with one third being slaves. Twice as many people again would have lived in the surrounding farms and villas. The coast of Campania was a favourite playground of Rome's well-to-do and so many of the villas were particularly grand with panoramic sea-side views. Even Nero (reign 54-68 CE) is thought to have had a villa near Pompeii and it is to be remembered that his wife Poppaea Sabina was a native of the town.

A Prosperous Trade Centre

The ancient city was one of the more important ports on the Bay of Naples and the surrounding settlements such as Nola, Nuceria and Aceria would have sent their produce to Pompeii for transportation across the Empire. Goods such as olives, olive oil, wine, wool, fish sauce (garum), salt, walnuts, figs, almonds, cherries, apricots, onions, cabbages and wheat were exported and imports included exotic fruit, spices, giant clams, silk, sandalwood, wild animals for the arena and slaves to man the thriving agricultural industry. On the subject of food, besides the foodstuffs mentioned above, we know that the diet of Pompeians also included beef, pork, birds, fish, oysters, crustaceans, snails, lemons, figs, lettuce, artichokes, beans and peas. Although, some of these and other delicacies, such as honey-roasted mice and Grey Mullet livers, would only have been within the reach of the better-off citizens.

The town itself, in the Roman custom, was surrounded by a wall with many gates, often with two or three arched entrances to separate pedestrian and vehicle traffic. Within the walls, there are wide paved streets in a largely regular layout (with the exception of the rather haphazard southwest corner) but there were no street names or numbers. There is also evidence that traffic was limited to one direction in certain streets. The town presents an astonishing mix of several thousand buildings: shops, large villas, modest housing, temples, taverns (cauponae), a pottery, an exercise ground, baths, an arena, public latrines, a market hall (macellum), schools, water towers, a flower nursery, fulleries, a basilica, brothels and theatres. In amongst all of these were hundreds of small shrines to all kinds of deities and ancestors and around forty public fountains. In short, Pompeii had all the amenities one would expect to find in a thriving and prosperous community.

Pompeii had many large villas, most of which were built in the 2nd century BCE and they display the Greek colonial origins of the town. The typical entrance of these plush residences was a small street doorway with an entrance corridor (fauceis) that opened out into a large columned atrium with a rectangular pool of water (impluvium) open to the sky and from which other rooms, for example, a bedroom (cubicula) or dining room were accessed. Movable screens, often decorated with mythological scenes, separated rooms and in winter kept in the heat provided by braziers. Other common features were a tablinum or hall space where archives and valuables were kept and there was also a place for the ancestor cult (alae) so much a part of Roman family life. A striking feature of these residences is their magnificent floor mosaics which depict all manner of scenes from myths to the homeowner's business activities.

Many houses had a private garden (hortus) with statues, ornate fountains, vine-covered pergolas, canvas awnings and the whole surrounded by a peristyle. Many private residences even had areas dedicated to viniculture. The House of the Faun is a good example of the typical grander residence of Pompeii.

Many of the larger villas also had a permanent triclinium or eating area in the garden so that guests might dine outside on cushioned benches. Ten such villas even had systems of small canals running between the diners so that as dishes floated past they could take their pick of the delicacies on offer. Those villas without such charms often employed trompe-l'oeil wall paintings to give the illusion of landscape vistas. Indeed, the wall paintings from these residences have also given insights into a myriad of other areas of Pompeian life such as religion, sex, diet, clothes, architecture, industry and agriculture. They also, on occasion, revealed the status of the guests as seating was formally arranged so that the importance of the guest ascended as one went clockwise around the circle of diners and sometimes the wall decoration reflected the status of the guest who ate in front of it.

In complete contrast to the richer residences, slave quarters have also survived and they show the cramped, prison-like existence of this large section of the population. Other more modest architecture included basic two or sometimes three-storied residences, simple taverns and small buildings, nothing more than curtained cubicles, where lower-class prostitutes plied their trade.

Mount Vesuvius Awakes

The area around Mt. Vesuvius received its first warning sign that the mountain was perhaps reawakening when a massive earthquake struck on the 5th of February 62 CE. The quake measured 7.5 on the Richter scale and devastated the surrounding towns; even parts of Naples, 20 miles (32 km) away, were damaged. At Pompeii, few buildings escaped damage. Temples, houses and parts of the thick city walls collapsed, fires ravaged sections of the town and even sheep in the surrounding countryside died from the release of poisonous gases. The death toll was likely in the thousands rather than the hundreds. The water supply to the ancient city was also severely affected with damage to aqueducts and underground pipes. The recovery process was also hampered by the collapse of the bridge over the Sarno. Things were so bad that a significant portion of the population left the town for good. However, slowly, the town made repairs, some hasty and others more considered and life began to return to normal. The civic repairs and improvements must also have been spurred on by the royal visit of Emperor Nero in 64 CE, an occasion which led to the lifting of the ban on gladiator games imposed following the famous crowd riots in 59 CE.

Seismic activity continued for the next decade but it seems not to have unduly perturbed the population. Life, and repairs from the catastrophe of 62 CE continued until 79 CE. It was then, in high summer, that strange things began to occur. Fish floated dead in the Sarno, springs and wells inexplicably dried up and vines on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius mysteriously wilted and died. Seismic activity, although not strong, increased dramatically in frequency. Something was clearly not right. Strangely, although some people left the town, the majority of the population seemed to still not be too worried about the events that were unfolding but little did they know that they were about to face an apocalypse.

Volcanic Eruption in Pompeii, 79 CE

On the morning of 24th of August 79 CE (the traditional date, although a partial inscription discovered at the site in 2018 CE suggests the eruption was actually some time in mid-October) a tremendous bang signalled that the magma that had been building over the last thousand years had finally burst through the crater of Vesuvius. Fire and smoke bellowed from the volcano. At this point, it may have seemed that the mountain was doing nothing more than offering a harmless pyrotechnic display but at midday Mount Vesuvius erupted: An even bigger explosion blew off the entire cone of Vesuvius and a massive mushroom cloud of pumice particles rose 27 miles (43 km) into the sky. The power of the explosion has been calculated as 100,000 times greater than the nuclear bomb which devastated Hiroshima in 1945 CE. The ash that started to rain down on Pompeii was light in weight but the density was such that within minutes everything was covered in centimetres of it. People tried to flee the town or sought shelter where they could and those without shelter tried desperately to keep themselves above the shifting layers of volcanic material.

Then in the late afternoon another massive explosion rang the air, sending a column of ash six miles higher than the previous cloud. When the ash fell it was as much heavier stones than in the first eruption and the volcanic material that smothered the town was by now metres thick. Buildings began to collapse under the accumulated weight; survivors huddled near walls and under stairs for greater protection, some hugging their loved ones or clasping their most precious possessions. Then at 11pm the huge cloud hanging above the volcano collapsed from its own weight and blasted the town in six devastating waves of super-heated ash and air which asphyxiated and literally baked the bodies of the entire population. Still the ash kept falling and relentlessly the once vibrant city was buried metres deep, to be lost and forgotten, wiped from the face of the Earth.

Rediscovery & Archaeology

Pompeii was finally re-discovered in 1755 CE when work on the construction of the Sarno Canal began. Local stories of 'the city' were proved to have been based on fact when under just a few metres of volcanic debris lay an entire town. From then on, after a series of major excavations, Pompeii became an essential stopping point on the fashionable Grand Tour and included such famous visitors as Goethe, Mozart and Stendhal. Indeed, the latter perfectly captured the strange and powerful impression on the modern visitor of this immense window into the past when he wrote, '...here you feel as if, just by being there, you know more about the place than any other scholar'.

Besides architectural remains, scholars of Pompeii have been presented with a mine of much rarer historical artefacts, a real treasure trove of data providing unique insights into the past. For example, the quantity of bronze statues has led scholars to recognise the material was more commonly used in Roman art than previously thought. A particularly rich source of data has been skeletal remains and the possibility to take plaster casts of the impressions left by the dead in the volcanic material provide evidence that bad teeth were a common problem - enamel was worn away by stone chips in bread, residue from the basalt milling stone. Tooth decay and abscesses from an over-sweet diet were a common problem and tuberculosis, brucellosis and malaria were also rife. The skeletal remains of slaves, often found still chained despite the disaster, also tell a sad tale of malnutrition, chronic arthritis and deformity caused by overwork.

It has also been possible to reconstruct the daily life of the town through the wealth of written records preserved at the site. These take the form of thousands of electoral notices and hundreds of wax tablets, mainly dealing with financial transactions. The wax of these tablets has long since melted but often impressions of the stylus have remained on the wooden backing. Other invaluable sources of text include signs, graffiti, amphorae labels, seals and tomb inscriptions. Not only are such sources typically unavailable to the historian but also their variety permits an insight into sections of society (slaves, the poor, women, gladiators.) usually ignored or scantily treated in traditionally surviving texts such as learned books and legal records. We know that there were 40 festivals of one kind or another every year and that Saturday was market day. Graffiti, for example, tells us how a gladiator was 'the sighed-for joy of girls', a mosaic in the house of a local businessman proudly proclaims 'Profit is Joy' and corrections on tablets reveal the changing status of citizens over time. Something more than names and figures has survived, however. The unique archaeological evidence from Pompeii allows us the rarest of opportunities - the possibility to reconstruct the actual thoughts, hopes, despair, wit and even the very ordinariness of these people who lived so long ago.