Cochin, located on the southwest coast of India, was a Portuguese colony from 1503 to 1663. Known to the Portuguese as Cochim, it was one of several important cities on India’s Malabar Coast and a great trade centre for spices like pepper. Cochin was the administrative capital of Portuguese India until it was replaced by Goa in 1530.

A fort was built at Cochin in 1503, the first in Portuguese India, as the Europeans used the city as their first headquarters in the East. The great explorer Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) spent his last days in the city, and it remained a lucrative hub of the spice trade into the 17th century. The city was taken over by the Dutch in 1663, then the English in 1814, and finally gained independence with the rest of India in 1947. Today, the city is known as Kochi and is the most prosperous port in the Kerala region of India.

Vasco da Gama

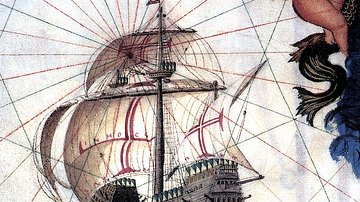

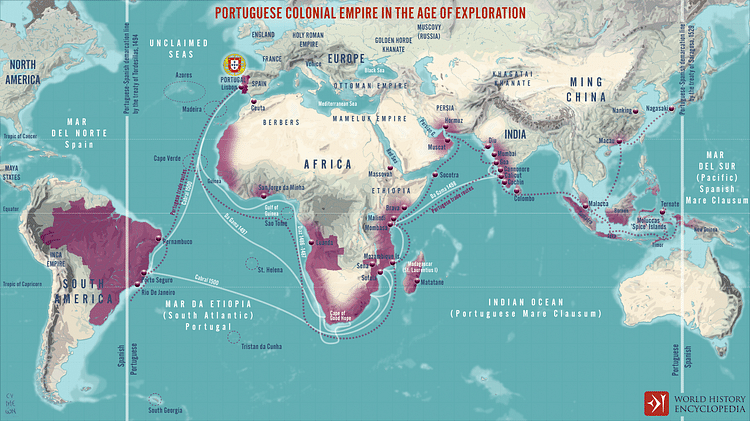

In the 15th century, the Portuguese colonization of Madeira in the North Atlantic from 1420 was the first in a series of colonial stepping stones that eventually led to India. The treacherous Cape Bojador in West Africa was negotiated in 1434, the Azores were colonised from 1439, Cape Verde from 1462, and São Tomé and Principe from 1486. In 1488 Bartolomeu Dias sailed down the coast of West Africa and made the first voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, the southern tip of the African continent (now South Africa).

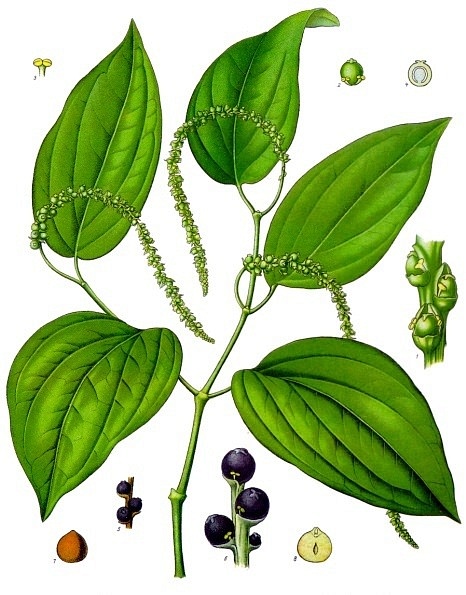

The famed Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama followed in Dias’ wake and pioneered a maritime route from Portugal to India when in 1497-9, he sailed around the Cape of Good Hope, went up the coast of East Africa, and crossed the Indian Ocean to arrive at Calicut (now Kozhikode) on the south-west coast of India. His voyage, supported by King Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1495-1521), was intended to find a legendary Christian kingdom in the East and to give Portugal direct access to the Eastern spice trade and cut out the Arab middlemen traders. The first aim ended up being an illusion but the second was indeed achieved. For the first time, Europe could access by sea a trade which had been going on for centuries but which channelled luxury goods through the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf to be then taken by camel caravan to the Mediterranean. Such goods as pepper, ginger, cloves, and cinnamon were immensely popular in Europe and expensive.

Vasco da Gama, through a mix of inexperience, lack of trade goods, and Indian confidence in the status quo, failed to establish friendly trading relations with Calicut. A second Portuguese expedition, this time with 13 ships and 1500 men and commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral, set off to repeat da Gama’s feat in March 1500 and was given the brief of muscling-in on Muslim trade by sinking any Arab ships they came across. Vasco da Gama sailed for a second time to India in 1502-3, this time with 15 ships. A result of this voyage was more trouble with the ruler of Calicut, but a trade treaty was agreed with Cochin further down the coast.

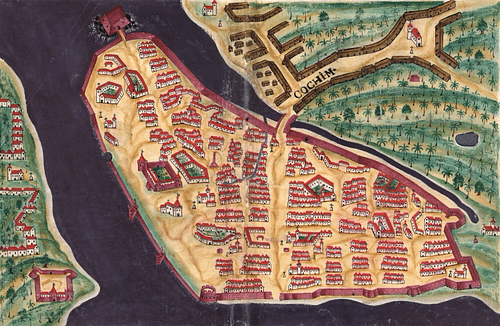

The Port of Cochin

Cochin had been a busy trading port for 150 years before the Portuguese arrived. A particularly bad monsoon had silted up the coastal area in 1341 and a local prince had taken advantage of the creation of a new advantageous topography to found a new port. Slowly, the city grew on a spur of land which was surrounded on three sides by woodlands and on the fourth by the sea. The harbour areas consisted of a group of waterways and calm lagoons created by the silted outflow of seven converging rivers. It was the ideal spot for loading and unloading cargo ships. With the best harbour on the Malabar coast, Chinese traders were attracted to Cochin and their influence could be seen by the Portuguese in the style of suspended fishing nets still in use. The Chinese Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644) had since withdrawn as a part of its wider isolationist foreign policy. There was a significant community of Jewish traders in Cochin.

The current ruler of Cochin, Unni Goda Varma, was nominally under the suzerainty of the ruler of Calicut and so any Portuguese assistance to finally establish his dominance over that city was most welcome. Ambassadors from Cochin went with da Gama back to Portugal and took with them a tribute for King Manuel. Da Gama left a factor, Diogo Fernandes Correia, to look after Portuguese trade interests in the town and the remaining Christians. Cochin, then, looked the most promising place to do business, but actually acquiring precious spices would prove more difficult than imagined.

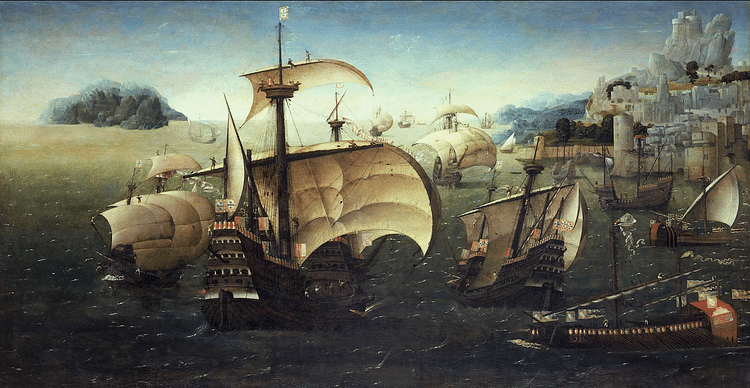

Portuguese Control of the Indian Ocean

The real problem for the Portuguese in their trading ambitions in the East was that they did not really possess any goods the Indians desired. Centuries of profitable relations with Muslim traders on the Swahili coast of East Africa and in the Persian Gulf had already made them immensely rich, and they were loath to make any changes to a regional trade network that was working extremely well and, more importantly for everyone, peacefully.

What the Portuguese did have was far superior weaponry, especially their naval guns. Indian rulers and some Arab traders did have some cannons, but these were not of the same quality as the European ones, and more significantly, Muslim trade ships were built for cargo and speed, not for naval warfare. The Europeans, in contrast, had been fighting sea battles for some time. The solution was simple, then: take over the Indian Ocean trade network by force and establish a monopoly on the spice trade. Such control would permit the Portuguese to buy the goods cheaply in the East and then, after shipping them to Europe, sell at much higher prices without any competition from elsewhere. Thus began a policy of sinking rival vessels on sight, blasting coastal trade centres into submission, and confiscating whatever goods were considered of value wherever they might be found. The Portuguese established a fully-armed naval force which permanently patrolled the Indian Ocean. In addition, forts were built to protect Portuguese interests, and the first was established at Cochin, the Fort Manuel, in 1503. The wooden fort and its garrison were needed in 1504 when Duarte Pacheco Pereira (c. 1450 - c. 1526) led a successful defence against the Samudri of Calicut, who had at one point taken over the town, and earned himself the nickname the "hero of Cochin". In 1506, a more permanent fort was built at Cochin with the permission of Unni Goda Varma who was eager to prevent a repeat attack from his enemies the Samudri.

Portuguese Colonization

In 1505, King Manuel was convinced enough of Portuguese control of the Indian Ocean to appoint a Viceroy of India, one Francisco d’Almeida. This was hopelessly ambitious as the Europeans at this point had no means to colonize an entire subcontinent or even a slice of it, but it was certainly a declaration of intent. The starting point for this Eastern empire was Cochin, which became the administrative capital of the Estado da India, the collective name given to the Portuguese colonies east of the Cape of Good Hope. In 1509, colonization gathered apace under the new viceroy, Afonso de Albuquerque, who served until his death in 1515. More forts were built, Portuguese Goa was established in the north in 1510, and as imperial tentacles stretched ever further, Malacca in Malaysia was taken over in 1511, Hormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf in 1515, and a fort established at Colombo in Sri Lanka in 1518. Every corner of Eastern trade was being brought into the Portuguese Empire, which although not grand in terms of territory, was hugely impressive in terms of the string of coastal trading pearls it had strung for itself across half the globe.

Portuguese colonization was not, then, directly concerned with territory, ousting rulers, or culturally dominating indigenous peoples. Missionaries did try and convert people to Christianity but the colonization really expressed itself in the desire to control trade. Cochin was a typical example of this policy where the indigenous population and the ruling class were permitted to continue their lives in what became known as the Cochim de cima area around the port, royal palace, and temples (what is today the Mattanchery district). The Portuguese community, on the other hand, inhabited the area around their fort (Fort Kochi, today) where they built churches and streets with Portuguese-style buildings. By the 1520s the Portuguese in Cochin numbered over 5,000 people.

Colonial Government

The apparatus of government was created for the primary goal of controlling commerce. The Portuguese viceroy, effectively the civil and military governor of Portuguese India, was, in theory, accountable only to the king. Religious affairs were led by an archbishop and legal matters were the responsibility of a High Court. A captain led the military force, which usually resided in a fort, and a factor was responsible for royal trade and extracting the lucrative customs duties from other types of trade. This was the colonial model applied at Cochin and elsewhere.

The viceroy was assisted by a ruling council, but in the first half of the 16th century, this was an informal body called whenever the viceroy needed specific advice and its membership varied depending on the expertise required. Only from 1604 would a formal Council of State be formed. Vasco da Gama was appointed Viceroy in 1524, but he died shortly after arriving at Cochin. He was interred in the Santo António church in Cochin, but his remains, as he had wished, were then returned to Portugal some years later. Each colony had its own local council, which was elected by the Portuguese and Eurasian citizens of the European settlement. By 1530, Goa had grown in importance, and it became the new administrative capital of Portuguese India, although officials still transferred to Cochin during the monsoon season.

A rivalry developed between Portuguese Goa and Cochin with Dom Aires da Gama, brother of Vasco, displaying a distinct preference when he reported to the king that "Cochin is the thing in India of which Your Highness has the greatest need" (Subrahmanyam, 274). With the decline of Calicut, Cochin was indeed now the spice capital of the Malabar coast. From 1523 to 1610, every year, a royal vessel sailed from Cochin to the Spice Islands (the Maluku Islands or the Moluccas) and back again, a round trip that took at least 23 months and often 30. Goods taken from Cochin and exchanged for spices like cloves, nutmeg, and mace included Indian-made cotton goods, dry foodstuffs, and copper. Other Cochin ships sailed to the Persian Gulf, Sri Lanka, the Bay of Bengal, and Portuguese Macao, where spices and other goods were re-exchanged for silver, fine textiles, and rice.

The Portuguese Monopoly

The Portuguese made a tremendous go of establishing a monopoly both of trade between Asia and Europe and within Asia itself. The Portuguese Crown issued all kinds of decrees that resulted in any private trader - European or otherwise - caught with a cargo of spices being arrested, his wares and ship confiscated. Muslim traders fared the worst and were often executed. After it was realised this policy was impossible to enforce everywhere, some local traders were permitted to trade spices in limited quantities, but often only one, most commonly pepper. Crews of European ships were permitted to take quantities of spices as a substitute for pay.

Another way to control the spice trade, and that in other goods, was to only permit ships to visit certain ports, for example Portuguese Macao, if they had a royal license. In short, the seas were no longer free. Even ships trading goods other than spices had to travel with a Portuguese-issued passport or cartaz, and if they did not, the cargo and the ship were confiscated and the crew imprisoned or worse. In addition to the cartaz, ships had to pay customs duties at their port of call. Yet another method to extract duties was to oblige all ships to sail in Portuguese-protected convoys, the cafilas. There was a threat from pirates in the Indian Ocean and beyond, but the real purpose was to ensure all trading ships stopped at a port like Cochin where they would have to pay duties (plus leave a cash deposit guaranteeing they returned to make a second payment). In these various ways, customs duties came to account for some 60% of the entire Portuguese revenue in the East.

The trade on the Indian Ocean was undoubtedly destabilised by the Portuguese presence, and this disruption did not leave Cochin unaffected. Vasco da Gama had noted on his third visit the difference in the prosperity of the town compared to his first two trips. Warehouses were now often empty, and the river silted up, in places blocking harbours. Indeed, to sweeten the ruler of Cochin and compensate him for the loss of revenues this decline brought, he was permitted from 1530 to extract his own customs duties from traders resident in the city.

Battleground

Naturally, neither Portugal’s trade rivals in the Islamic world or their fellow-European kingdoms were keen to sit back and watch massive revenue opportunities slip away and become dominated by one state. In addition, as the 16th century wore on, the Portuguese Crown frittered away its earnings on immensely costly forts and fleets, not to mention the overlavish lifestyle of the monarchy. There was, too, a revival in the Middle East land and sea routes to transport spices to meet an ever-increasing demand in Europe. Arab, Indian, and other traders continued to avoid the Portuguese attempts at monopoly, aided by the sheer size of the geographical area the Europeans were trying to police. There were, too, plenty of corrupt Portuguese officials who conducted their own private illegal trade to avoid customs duties. Some local rulers even opted for armed resistance. Even peaceful Cochin was not so glad to welcome Christian missionaries, and those locals who did convert to Christianity were often discriminated against by their peers. Overambition, mismanagement, and a thriving ‘illegal’ trade all meant the Portuguese did not get quite as rich as they had hoped on the spice trade, and now the world was changing again as European colonization in the East became territorial.

From the early 17th century, other European powers now wanted to directly involve themselves in the Eastern trade bounty, notably the Venetians and the Dutch. The Dutch arrived in Southeast Asia in 1596 and from there steadily took over many Portuguese trading centres such as Malacca (1641) and Colombo (1656). They took over Cochin in 1663 after a four-year siege, blockading Goa at the same time. Portugal was struggling to police the vast spread of its empire and many forts suffered from a lack of upkeep making them relatively easy targets.

Meanwhile, the Persians, with English assistance, had taken over Hormuz in 1622. The Hindu Marathas were also winning great victories in southern India. The Dutch were causing some serious problems in Portuguese Brazil, too. The Portuguese Empire, such as it was, was crumbling away while events back home were also worrying as a war rumbled on with Spain from 1640 until 1668. Although the Portuguese still continued to trade, albeit on a lesser scale than before, and they did keep some outposts such as Goa, Cochin was never recovered. In 1814 the Dutch handed Cochin over to the British. In 1947, Cochin joined India when it became free from British rule. Today, Cochin thrives as a major Indian port under the name of Kochi.