Nagasaki, on the northwest coast of Japan’s Kyushu Island, was an important Portuguese trading base from c. 1571 to 1639, and the most eastern outpost of the Portuguese empire. The Portuguese presence transformed Nagasaki from a small fishing village into one of the great trade centres of Japan and East Asia.

Only briefly under direct Portuguese administration (1571-1614), the city was used as an access point to the lucrative Japanese market where goods like silk, silver, and gold were exchanged between China, Portuguese Macao, and Lisbon, as well as many other colonial outposts in Asia. The Portuguese presence came to an end in 1639 when the Japanese military government or shogunate decided to expel all foreigners from the Japanese mainland.

The Portuguese Empire

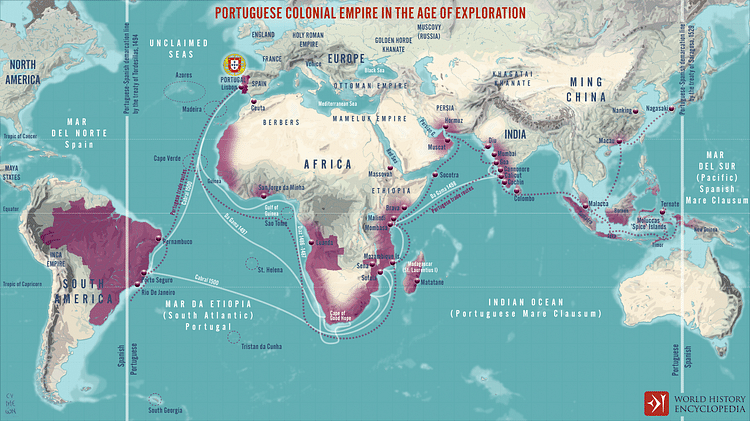

Ever since 1497-1499, when Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) had sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and shown the possibilities of a maritime route between Europe and Asia, the Portuguese had been busy building an empire. Portuguese Cochin was founded in 1503, and Portuguese Goa was established in 1510. Portuguese Malacca in Malaysia was set up in 1511. The Portuguese sailed relentlessly eastwards, and c. 1557 Portuguese Macao was established on the coast of southern China near Guangzhou (Canton). This gave the Portuguese merchants direct access to the trade fairs of Canton where such goods as precious silk could be acquired. Always eager for more, the Europeans next wanted a foothold in Japan.

Three Portuguese mariners were the first Europeans to set foot on Japanese soil in September 1543, albeit by accident. These intrepid traders were on board a Chinese junk, which was aiming for Ningpo in China, but the junk’s Chinese pilots could do little to prevent a storm blowing them to western Japan and the island of Tanegashima. Significantly, the Portuguese were carrying firearms, and these greatly impressed the Japanese, even if these were crude harquebuses. Oda Nobunaga would import these handy weapons and use them to great effect when he established himself as Japan’s foremost military leader between 1568 and 1582.

The Port of Nagasaki

Nagasaki is located on the northwest coast of Kyushu, Japan. The Portuguese established a permanent presence there from c. 1571 when the viceroy of the Portuguese Indies (Estado da India) based at Goa decided that this should be the principal base for their China-Japan trade. Nagasaki was a modest fishing port when the Portuguese arrived, but it would be transformed into a thriving trade centre that eventually became one of the major cities of Japan. The state of Japan was not yet fully unified, and Nagasaki harbour was given as a fiefdom to the Portuguese by Omura Sumitada, a daimyo (feudal lord) from Hizen in the northwest of Kyushu. Specifically, the port was handed over to the Jesuit Gaspar Vilela who was selected thanks to persuasion by a vassal of Sumitada’s. Both Japanese men had recently converted to Christianity. The handover occurred c. 1571, but the formal deed was not signed until 1580. As a bonus, Sumitada gave the Jesuits the nearby fortress of Mogi. A condition was that there would be no permanent Portuguese military presence in the port area.

The port was, then, administered by the Jesuit Society of Jesus, and it was their only sovereign territory. Nagasaki thus became an important headquarters of Jesuit missionary work in East Asia. Missionaries, beginning in 1549 with the Spaniard Jesuit Francis Xavier (aka Francisco de Javier, l. 1505-1552), spread Christianity with surprising success in Nagasaki and the surrounding region. Indeed, the religion remains significant in the city even today. The Jesuit management of Nagasaki lasted until 1614. After this date, the Portuguese were content to maintain a trade-only foothold in the lucrative Japanese market. Nagasaki remained the most eastern outpost of the Portuguese Empire.

The Portuguese base of merchants, missionaries and immigrants at Nagasaki prospered for around 60 years. The port was (despite the original agreement) given fortifications, and a large cathedral was built to replace the early chapel built by Vilela. Most of the permanent residents were Japanese Christians who had converted from Buddhism, while Portuguese traders tended to visit only for trade purposes and so lived in temporary residences. Unlike in other colonies, there was not a great deal of social relations with the local people and intermarriages which produced a new (lower) class of mixed-race descendants. Rather, the temporary traders at Nagasaki were content to make use of young Japanese prostitutes sent to the port for that express purpose by families keen to acquire a dowry for their daughters that could then be used to marry a Japanese man back home. The port was not formally part of the Portuguese Empire, a situation that was familiar to other ports in Asia where the Portuguese had established a presence and trading concessions with the local government.

The East Asian Trade Network

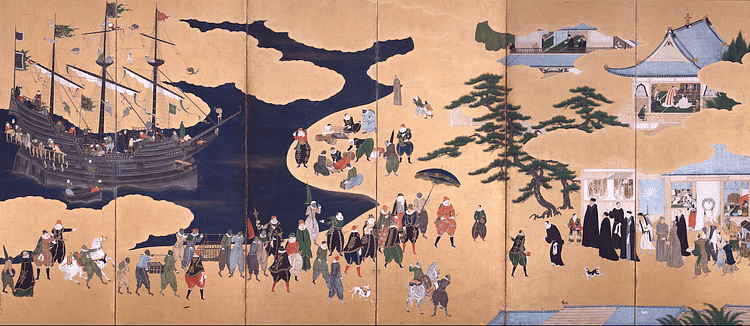

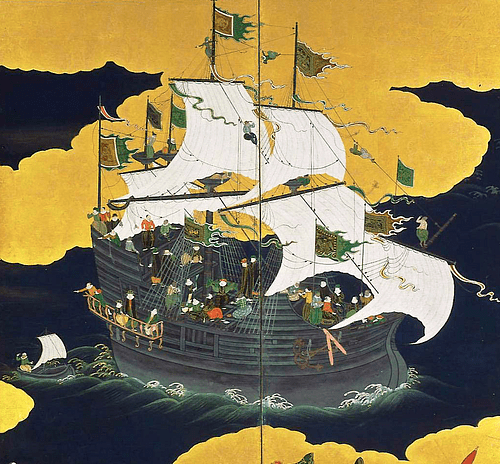

Following the establishment of Portuguese Nagasaki, each year until 1618, a single large carrack vessel, the ‘Great Ship’, sailed from Macao to Japan (having arrived from Goa). From 1619 to 1639 this single ship was substituted with a fleet of smaller vessels. The large Portuguese carrack cargo ships that plied the route between Macao and Nagasaki had Chinese pilots but were packed with goods and Portuguese traders who appear on Japanese screen paintings of the period. The carracks themselves appear on these screens, too, the 'black ships' as the Japanese called them because of their treated hulls designed to keep marine parasites at bay. The Japanese called these foreigners Nanbanjin ('southern barbarian people') and the trade with them the 'Nanban trade'.

Goods exported from Japan included silver (from the mines on Honshu), copper, painted screens, lacquerware, cabinets, kimonos, swords, and pikes. The Portuguese ships were able to bring silk, gold, and Ming porcelain from their contacts between Canton and Portuguese Macao, and spices and other goods from their Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia trade networks.

The British and Dutch arrived to cash in on the Japan trade from the early years of the 17th century and were permitted by the Japanese authorities to trade, even if the Portuguese at Nagasaki tried to have their European rivals executed as pirates. Despite the new competition, the Portuguese traders in Nagasaki continued to thrive for another three decades.

The Tokugawa Shoguns

Relations with Japan began to turn sour from the 1630s when the Japanese government, the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868), began to detain Portuguese vessels arriving at Nagasaki. The confiscations were a direct result of a Spanish captain hijacking a Japanese junk. Since Spain and Portugal were now unified, the Japanese treated ships of both nations in the same way. The shoguns then imposed a trade embargo on the two European kingdoms. A representative was sent from Macao to Japan in 1630, one Dom Gonçalo de Silveira, to try and negotiate a lifting of the ban. It took the emissary four years but, at last, the Japanese government consented to resume trade with the Portuguese. It was to be a temporary respite.

Things got much worse for the Portuguese in 1639 when two of their ships returned to Macao with the disturbing news that they had not been allowed to lower anchor and unload at Nagasaki. The Tokugawa shoguns had formally changed their foreign trade policy. As the military leaders of Japan grew suspicious of foreigners and the spread of Christianity, all Portuguese were expelled from the country and trade halted with the likes of Macao. Even Japanese people abroad were not permitted to return home and if they tried, execution awaited them. The catalyst for this expulsion had been the Shimabara Rebellion of December 1637 to April 1638. The shogunate blamed the uprising on the Shimabara peninsula of Kyushu on Christians, although many of the 35-40,000 people killed during the disturbance were of that religion and many of the protestors were peasants unhappy over tax increases and were not concerned with religious matters.

Macao sent delegates to the Tokugawa shogun to negotiate a reopening of Portuguese trade in 1640, but these four unfortunate ambassadors were imprisoned, tried, and then executed along with 57 of their attendants and crew. The trade was never revived and even a visit from a royal ambassador of the Portuguese king in July-August 1647 brought no change of policy, but at least he was allowed to return to Lisbon.

This period of cultural isolation, known in Japan as the Sakoku Period (‘chained off nation’), continued until the mid-19th century, even if a very small number of Dutch traders were permitted to stay on the tiny man-made island of Dejima in the Nagasaki Bay. The Dutch could not leave the island without express permission from the shogun, and they seem to have been tolerated because they had no interest in spreading their religion. Not until the mid-19th century did European ‘foreign devils’, particularly the British and Americans, return to live and trade in Japan.