The autumn of 1793 saw the Jacobins consolidate their authority in France as the Reign of Terror intensified and the Jacobins' defeated rivals were executed by guillotine. Yet the dominant Jacobins disagreed over the direction the French Revolution (1789-1799) should now take, causing them to devolve into factionalism. The ensuing power struggle ended with a victory for Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794).

Dictatorship by Committee

The declaration of Terror as 'the order of the day' on 5 September 1793 signaled the beginning of the rule of the Committee of Public Safety, a body of twelve men whose tight grip on France has sometimes been characterized as a Jacobin dictatorship. The ostensible purpose of the Committee's Reign of Terror was to save the French Republic from the bad actors corrupting its body politic – to sacrifice a gangrened limb to save the rest of the body, in the colorful words of Committee member Jacques Billaud-Varenne.

In the spirit of such patriotic amputation, the Committee enacted the Law of Suspects on 17 September, which led to the arrests of hundreds of thousands of people nationwide, accused of counter-revolutionary activity. The Committee's tight control over the French military led to the brutal suppression of the anti-Jacobin federalist revolts, as well as a string of successes in the French Revolutionary Wars against the powers of Europe. Additionally, the Jacobins consolidated their power by sending their old rivals beneath the guillotine's blade; moderate Girondins, monarchist Feuillants, and old regime aristocrats died one after the other, their blood filling the gutters of Paris.

As the pile of bodies mounted, the Revolution itself ground to a halt. On 10 October, the National Convention agreed that France's provisional government would remain revolutionary (i.e. dictatorial) until the peace, and the new Constitution of 1793 was shelved before it could ever be implemented. For the famously self-righteous Robespierre, who believed moralistic virtue to be the most important quality of a healthy republic, this was necessary to both cleanse the body politic and win the foreign war. Other Jacobins were uneasy with an indefinite pause to a seemingly endless revolution and advocated for different courses of action.

The Hébertists

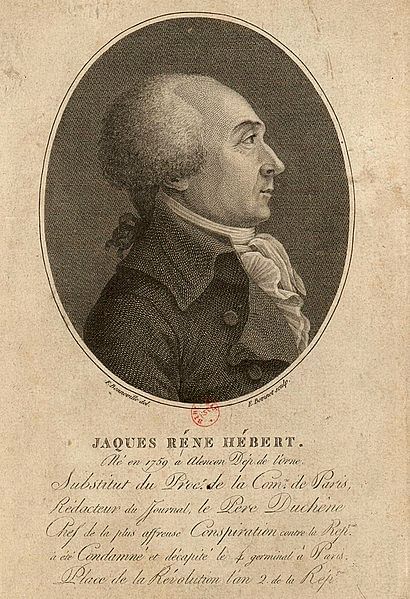

On the extreme left were the Hébertists, who claimed the role of the voice of the lower-class sans-culottes and who dominated the radical Cordeliers Club and the Paris Commune. The Hébertists called for an acceleration of the Terror and an escalation of the Revolution itself, which took the form of attacks against religion; the Hébertists oversaw many of the programs of dechristianization carried out during the Terror and propped up their own atheistic Cult of Reason. This group was led by relative newcomers to revolutionary leadership including Pierre Gaspard Chaumette, Charles-Philippe Ronsin, and of course, Jacques René Hébert, the journalist after whom they were named; Hébert's popular and obscenity-ridden newspaper, Le Père Duchesne, filled the void for provocative calls to action left by the assassination of Marat.

Robespierre and the entrenched Jacobin leadership wrote off the Hébertists as ultra-revolutionary agitators who wanted nothing more than to steal their government positions. Robespierre, who agreed with Voltaire that belief in a higher power was essential for civic well-being, was disgusted by the Hébertists' anticlerical brand of atheism, and felt threatened by their calls for more radical measures; certainly, Robespierre believed, the Hébertists would only alienate neutral nations from the Revolution and drive more French provinces to rebellion. Prominent French historians have been no kinder to the Hébertists, with Jules Michelet describing them as "weasels with pointy snouts ideally adept for sniffing blood" (Furet, 363).

On 5 September 1793, Hébert and Chaumette had led an insurrection on the National Convention, demanding fixed prices on bread and the deaths of counter-revolutionary conspirators. While this event began the Terror and led to the rise of the Committee of Public Safety, Robespierre and his allies were distrustful of the Hébertists' ambitions. Over the next two months, the Hébertists' anti-Christian policies became more egregious as churches across France were vandalized or rededicated to Reason, including the Notre-Dame in Paris. Christian iconographies were replaced with revolutionary images, while priests were humiliated and even forced to marry. The French Republican calendar was created to erase Christianity from the minds of the public, and in Nantes, scores of priests and nuns were drowned in the freezing Loire River. For the virtue-obsessed Robespierre, it was vital that the Hébertists be stopped before they permanently corrupted the soul of the Republic. All that he needed was an excuse to bring them down.

The Indulgents

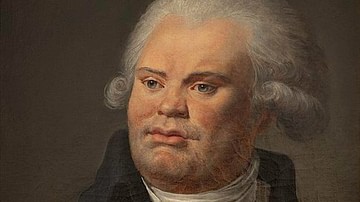

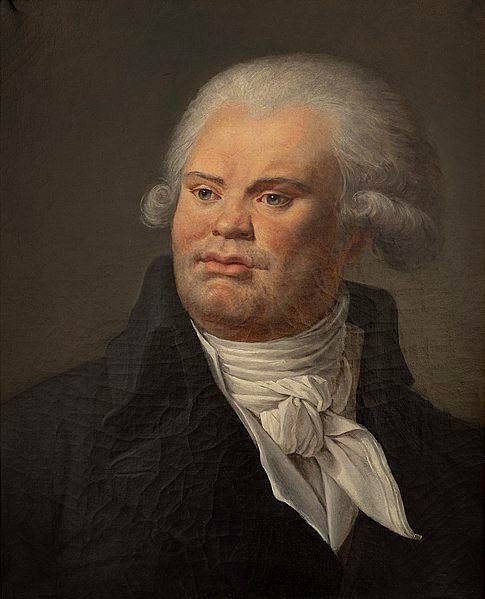

The primary challenge to the Hébertists would not come directly from Robespierre but from a group of Jacobins who sought to scale back the Terror and who wished to prevent the Hébertist-led Paris Commune from accumulating more power. This group, called the Indulgents, took on the title of the Revolution's moderate faction, made vacant by the fall of the Girondins. Centered around Georges Danton (1759-1794), the Indulgents, or Dantonists, called for peace to be made with the European powers and for thousands of counter-revolutionary suspects to be amnestied. Some even wished to end or regress the Revolution.

Danton, who had once urged the government to be 'terrible' so the people would not have to be, perhaps adopted this more lenient approach in a pragmatic attempt to save the Republic. Yet Danton had also recently suffered the death of his first wife and had lost control of his beloved Cordeliers Club to the Hébertists. Possibly, he was truly ready to bring the Revolution to a close; perhaps the revolutionary titan with the booming voice was tired.

Of the other prominent Jacobins who became Indulgents, some did so because they regretted the role they had played in bringing the Terror into existence; when the death sentence was pronounced against 22 Girondin leaders on 30 October, Camille Desmoulins (1760-1794), whose newspapers had helped turn public opinion against them, was heard to cry, "My God! My God! It is I who kills them!" (Scurr, 289). Others were motivated by self-preservation. This was the case with Fabre d'Eglantine, poet, a long-time friend of Danton's, and father of the French Republican Calendar. Fabre had become embroiled in a plot by several deputies of the National Convention to enrich themselves through the liquidation of the French East India Company, by bribing and extorting former directors. Knowing that the moralizing Jacobins would be unlikely to forgive such corruption should the scandal be brought to light, Fabre sought to knock them off his trail and advance the Indulgent cause in one swift stroke, by throwing the Hébertists under the bus.

Foreign Plot

Fabre approached Robespierre in mid-October, warning him of a 'foreign plot' to undermine the National Convention and topple the Republic. Supposedly masterminded by British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806), the plot was allegedly being carried out by agents who had infiltrated the Revolution; Fabre specifically named the Prussian-born Anacharsis Cloots as well as one of Robespierre's colleagues on the Committee of Public Safety, Hérault de Séchelles. More importantly, Fabre accused the Hébertists of being involved.

Whether Robespierre truly believed Fabre or not, this was a golden opportunity to tear down his enemies. Two prominent Hébertists, Ronsin and François-Nicolas Vincent, were arrested alongside several of the foreign 'agents' implicated by Fabre. On 16 October, Robespierre's young ally and protégé Louis Antoine de Saint-Just (1767-1794) gave a speech denouncing the Hébertists; Robespierre himself spoke against them on 21 November, condemning atheism as 'aristocratic'. On 5 December, journalist Camille Desmoulins started a newspaper entitled Le Vieux Cordelier (the old Cordelier) in which he denounced the excesses of the Hébertists and called for clemency to those imprisoned under the draconian Law of Suspects. Beneath this incessant onslaught, the Hébertists went quiet.

Robespierre and his allies took advantage of this victory and were able to implement the Law of 14 Frimaire in December, which further centralized power in the hands of the Committee of Public Safety, cementing its role as the de facto government of France. This law would later be known as the 'constitution of the Terror'; amidst the battle between the Indulgents and Hébertists, the Committee's power only grew.

Le Vieux Cordelier

Meanwhile, Desmoulins continued to print his Le Vieux Cordelier, which had proved immensely popular, showing that many people had already grown weary of the Terror. The first two issues had primarily been directed against the Hébertists and had both been approved by Robespierre before publication. Now that the Hébertists had gone quiet, Desmoulins saw no reason to stop and continued to speak out against the Terror in his next two issues.

Issue 3 of Le Vieux Cordelier called into question the authority of the dreaded Revolutionary Tribunal, while Issue 4 was a direct appeal to Robespierre himself to put an end to the bloodshed. In these issues, Desmoulins also took the dangerous step of advocating a return to the revolutionary principles of 1792 – pre-Terror and pre-Jacobin rule. This idea was not taken kindly by many Jacobin leaders; while they had resisted the chaotic acceleration of Terror by the Hébertists, there was still much to be gained by keeping the Terror going under their control. Moreover, Robespierre had not pre-approved the contents of these latter issues, making him feel undermined. Desmoulins' friends could tell that he was overstepping himself; "Camille," one of them warned, "you seem very close to the guillotine" (Scurr, 299). But Desmoulins disregarded these warnings, confident in his friendship with Robespierre, who had been his old schoolmate.

Indeed, Robespierre initially kept his patience with Desmoulins, shrugging him off as an unthinking youth led astray by bad company. One night at the Jacobin Club, Robespierre publicly resisted calls to expel Desmoulins from the Jacobins, instead suggesting that it would be enough to burn Desmoulins' pamphlets. In response, Desmoulins, quoting Jean-Jacques Rousseau, exclaimed, "Burning is no answer" (ibid). Immediately, Robespierre's expression darkened. Desmoulins, who knew that Rousseau was Robespierre's idol, had deliberately used the quote to provoke his old friend. Turning toward Desmoulins, Robespierre erupted in anger:

What! You try and justify your aristocratic works! Understand this, Camille, that were you not Camille there would be no indulgence for you. Your intentions are bad. Your citation: 'Burning is no answer'! Is it applicable here? (Scurr, 299)

Rather than backing down, Desmoulins made things worse, reminding Robespierre that he had shown him the drafts of his paper; Robespierre replied that he had only seen the first two. Things got so heated that Danton had to step in, urging Desmoulins to accept Robespierre's critiques. The damage, however, was done; the next night, Robespierre attacked Fabre d'Eglantine, whose involvement in the corrupt East India scandal had finally come to light. As expected, this act of immorality disgusted the 'Incorruptible' Robespierre, who attacked Fabre with such vitriol that he was forced to flee the Jacobin Club, hounded by loud cries of "guillotine him!" On 8 January 1794, Fabre was expelled from the Jacobins, as was Desmoulins two nights later.

Fall of the Hébertists

On 21 December 1793, Collot d'Herbois, member of the Committee of Public Safety, returned to Paris from his brutal suppression of the Revolt of Lyon. Himself an ultra-revolutionary, Collot was enraged by the treatment of the Hébertists in his absence, accusing his colleagues of having grown soft on counter-revolutionaries and demanding the release of Ronsin and Vincent. Such was granted, on the basis of a lack of evidence against them; with Collot's arrival, the Hébertists gained the confidence to go on their own offensive and attack the Indulgents.

Robespierre was in little mood to help them; with Desmoulins's newspapers and Fabre's corruption, he had been made to look a fool and was inclined to write off the entire Indulgent movement as nothing but hypocrisy. Shortly after his public argument with Desmoulins, Robespierre had collapsed, perhaps out of emotional exhaustion, and remained sporadically ill for the rest of January. He also spent much of February and March confined at home, leaving Saint-Just to take care of public appearances. In one of his increasingly rare speeches during this period, Robespierre attacked the Indulgents and Hébertists with equal fury:

In my view, Camille and Hébert are equally wrong…I assure all faithful members of the Mountain that victory lies within our grasp. There are only a few serpents left to crush. (Scurr, 302)

Reiterating Robespierre's sentiment, Saint-Just declared that there were three deadly sins against a republic: "one is to be sorry for state prisoners; another is to be opposed to the rule of virtue; and the third is to be opposed to the Terror" (Scurr, 305). Both the Indulgents and Hébertists satisfied the criteria of these crimes, of which Saint-Just insisted there was only one punishment: death. To avoid such a fate, the Hébertists decided to utilize their popularity with the sans-culottes. On 4 March, Hébert and Jean-Baptiste Carrier, back from overseeing the Drownings at Nantes, covered a bust of Liberty in the Cordeliers Club with a black veil, the signal for insurrection. Such a tactic had worked on 2 June to tear down the Girondins; it would not work now.

No throngs of angry citizens rose in revolt. Instead, Hébert and 19 of his most prominent followers were arrested. On 24 March, they were tried alongside those who were arrested for their alleged participation in the 'foreign plot'; Robespierre rightly assumed that trying the two groups together would increase the likelihood of a guilty verdict. The largest crowd to ever be assembled before a guillotine came out to watch Hébert die, followed by Ronsin, Vincent, Anacharsis Cloots, and the others; "they died like cowards without balls" said one onlooker (Schama, 816). Despite the Hébertists' claim to represent the people, the crowd felt little sympathy for their deaths, aware of how many heads had rolled because of them.

Fall of Danton

The deaths of the Hébertists left only the Indulgents standing between Robespierre and his idealistic republic. Fabre d'Eglantine had already been arrested for his part in the East India Company scandal, though it was clear he would not long be separated from his friends. On 22 March, Robespierre attended a dinner at which Danton was also a guest. During the meal, Danton asked Robespierre why there were so many victims of the Terror, and why so many innocents had to die. "Who says anyone innocent has perished?" Robespierre coldly responded (Scurr, 309).

Biographer Ruth Scurr describes this heated dinner, in which Danton spoke candidly with Robespierre, asking him to end the Terror for the good of France. But Robespierre, the 'Incorruptible', would not dare sacrifice his principles, not even to save lives. "I suppose that a man of your moral principles would not think that anyone deserved punishment,' snapped Robespierre. With an air of sadness, Danton replied, "And I suppose that you would be annoyed if none did" (ibid). Robespierre abruptly stood and stormed off leaving Danton, and any hope of reconciliation, behind.

That same evening, Robespierre allowed the Committee to add Danton's name to the list of proscriptions, something he had violently opposed before. Scurr writes that his signature on the arrest warrant was the smallest of his colleagues, perhaps a sign that he felt shame in sending a friend to the scaffold. One member of the Committee, Robert Lindet, boldly refused to sign the warrant, stating, "I am here to save the citizens, not to kill patriots" (Davidson, 216). According to one story, Danton went to see Robespierre one last time on 29 March, to again try and reconcile the differences between them. Upon walking into the assembly, Danton saw Robespierre engaged in an apparently friendly conversation with Camille Desmoulins. Relieved, Danton went home; he and Desmoulins were arrested that same night.

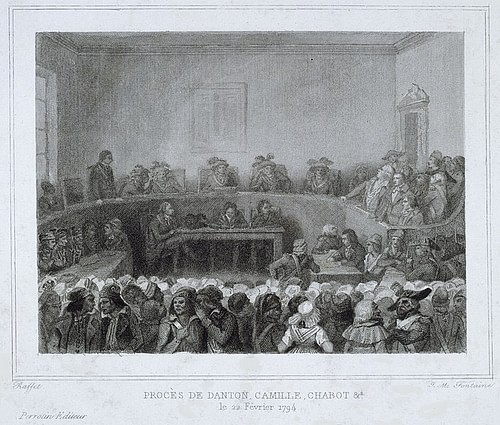

Danton was arrested alongside his closest friends, including Desmoulins and Pierre Philippeaux; for good measure, Robespierre also had Hérault de Séchelles arrested and tried beside them. Thanks to Fabre, they would all be tried in connection to the East India scandal, as well as a general charge of attempting to overthrow the government. On 2 April, the start of their trial, a large crowd packed the courtroom, a testament to Danton's enduring popularity; such would not save him now, a fact Danton well knew. When asked for his name and address, Danton grimly replied, "My abode will soon be nothingness, and my name in the pantheon of history" (Scurr 313). Still, he used his practiced theatrics to great effect, thundering on about his patriotism and the injustice of his trial until the Tribunal president ordered him to be silent.

Unsurprisingly, the guilty verdict was rendered. Danton spent his last hours trying to calm Desmoulins who panicked like a frightened child, asking over and over, "will they kill my wife too?" (Scurr, 316). On 5 April 1794, when the tumbril carrying the condemned rolled through the streets of Paris, Danton only lost his composure once, angrily ranting and raving when they passed Robespierre's residence. On the scaffold, Danton was the last to die, forced down beneath a blade that was covered with the blood of his friends. Defiantly, he looked at the executioner and said, "Show my head to the people. It will be worth seeing" (Davidson, 216).

With the deaths of the Hébertists and the Indulgents, the power struggles in the Reign of Terror were over. Robespierre had his victory, however hollow it must have felt. For three months he and his allies would continue to control France's destiny, further intensifying the Terror in their endless quest for a utopia of virtue. But the Hébertists and the Indulgents had surviving friends, who would help bring about the fall of Maximilien Robespierre on 27 July 1794 (9 Thermidor Year II), bringing an end to the Terror.