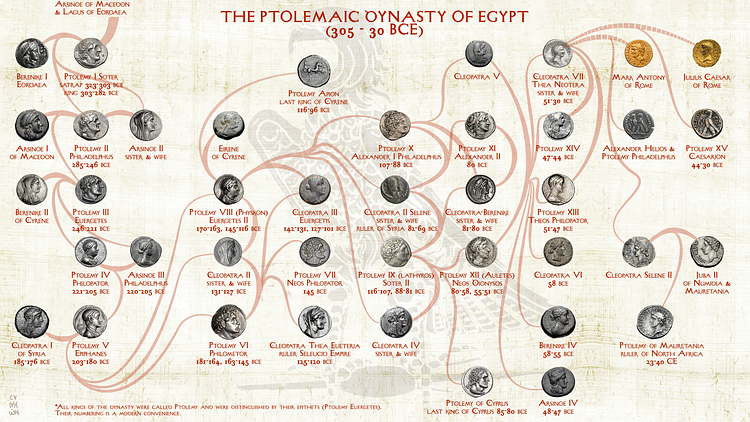

The Ptolemaic Dynasty controlled Egypt for almost three centuries (305-30 BCE), eventually falling to the Romans. Oddly, while they ruled Egypt, they never became Egyptian. Instead, they isolated themselves in the capital city of Alexandria, a city envisioned by Alexander the Great. The city was Greek both in language and practice. There were no marriages with outsiders; brother married sister or uncle married niece. The last Ptolemaic queen, Cleopatra VII (l. c. 69-30 BCE), remained Macedonian but spoke Egyptian as well as other languages. Except for the first two Ptolemaic pharaohs, Ptolemy I and his son Ptolemy II, most of the family was fairly inept and, in the end, only maintained authority with the assistance of Rome.

A Greek Family of Egyptian Pharaohs

One of the unique and often misunderstood aspects of the Ptolemaic dynasty is how and why it never became Egyptian. The Ptolemies coexisted as both Egyptian pharaohs as well as Greek monarchs. In every respect they remained completely Greek, both in their language and traditions. This unique characteristic was maintained through intermarriage; most often these marriages were either between brother and sister or even uncle and niece. This inbreeding was intended to stabilize the family; wealth and power were consolidated. Although it was considered by many an Egyptian and not Greek occurrence – the mother goddess Isis married her brother Osiris – these sibling marriages were justified or at least made more acceptable by referencing tales from Greek mythology in which the gods intermarried; Cronus had married his sister Rhea while Zeus had married Hera.

Of the fifteen Ptolemaic marriages, ten were between brother and sister while two were with a niece or cousin. This meant that even Cleopatra VII, the last Ptolemy to rule Egypt and the subject of playwrights, poets, and movies, was not Egyptian but Macedonian. According to one historian, she was a descendant of such great Greek queens as Olympias, the overly-possessive mother of Alexander the Great.

However, in her defense, Cleopatra was the only Ptolemy to learn to speak Egyptian and make any effort to know the Egyptian people. Of course, this inbreeding was less than ideal; jealousy was rampant and conspiracies were common. Ptolemy IV supposedly murdered his uncle, brother, and mother, while Ptolemy VIII killed his fourteen-year-old son and chopped him into pieces.

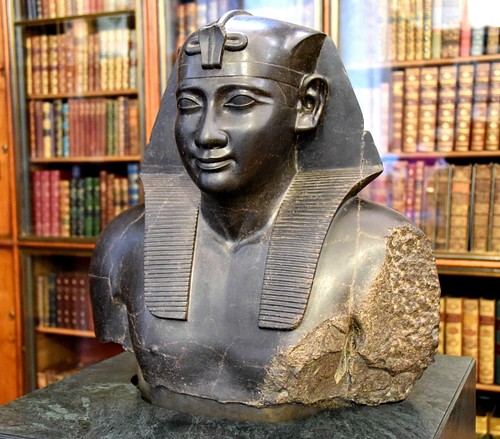

Ptolemy I Soter

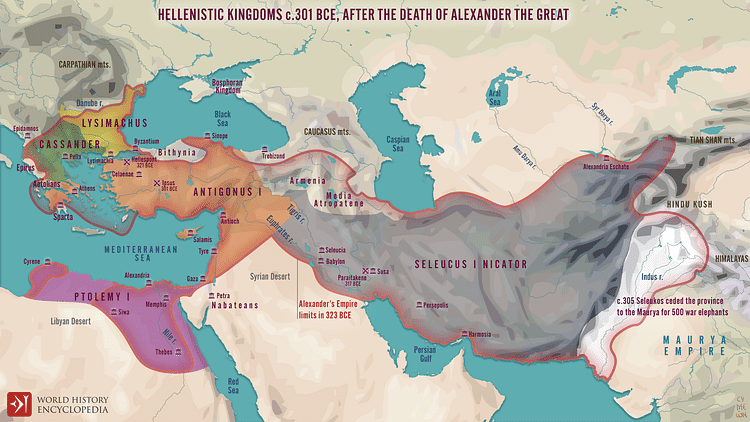

The sudden death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE brought chaos and confusion to his vast empire, for he died without naming an heir or successor, saying instead that the empire was left 'to the best.' Those commanders who had faithfully followed him from Macedon across the desert sands of western Asia were left to decide for themselves the fate of the kingdom. Some wanted to wait until the birth of Roxanne and Alexander's son, the future Alexander IV, while others chose a more immediate and self-serving remedy: to simply divide it among themselves. The final decision would bring decades of war and devastation. The vast territory was split among the most loyal of Alexander's generals: Antigonus I the One-Eyed, Eumenes, Lysimachus, Antipater, and lastly, Ptolemy, the 'most enterprising' of Alexander's commanders.

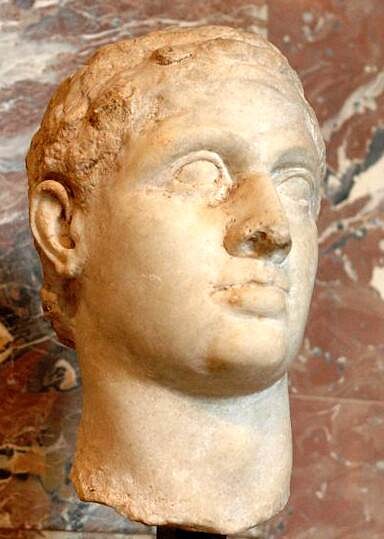

Ptolemy I Soter (Savior) (366-282 BCE) was a Macedonian nobleman and, according to most sources, the son of Lagos and Arsinoe. He had been a childhood friend of Alexander, his official taster, bodyguard, and even possibly a relative; rumors abound that he was the illegitimate son of Philip II, Alexander's father. After the king's death, he led the campaign to divide the empire among the leading generals and in the Partition of Babylon, and to his delight, he received the land he had always craved: Egypt. In Ptolemy's eyes, Egypt was the ideal land, rich in resources.

After years of oppression under the Persians, the people of Egypt welcomed Alexander and his conquering army. The Persian conquerors had been intolerant of Egyptian religion and customs. Alexander was far more tolerant, even embracing their gods and praying at their temples. He had even built a temple to honor the Egyptian mother goddess Isis. However, in Egypt, Ptolemy saw vast potential, albeit selfishly. There was wealth beyond measure, largely dependent on agricultural production; its borders were easy to defend with Libya lying to the west and Arabia to the east (he was wise not to trust his fellow commanders); and it was friendly to his home of Macedon.

Unfortunately, while the partition may have granted Egypt to Ptolemy, there were some who did not trust the cagey commander, namely Perdiccas, the self-appointed successor to Alexander. So Cleomenes of Naucratis, who had been named the Egyptian finance minister by Alexander, was appointed by Perdiccas as an adjunct or hyparchos to watch (or spy) on Ptolemy. Realizing Perdiccas' ploy, Ptolemy knew he had to free himself of Cleomenes, so he accused the unwary minister of 'fiscal malfeasance' - not a completely trumped-up charge - and had him executed. With Cleomenes gone, he could now rule alone without anyone watching over his shoulder, and in doing so, he would establish a dynasty that would last for almost three centuries until the time of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra VII. During Ptolemy's four-decade rule of Egypt, he would put the country on sound economic and administrative footing.

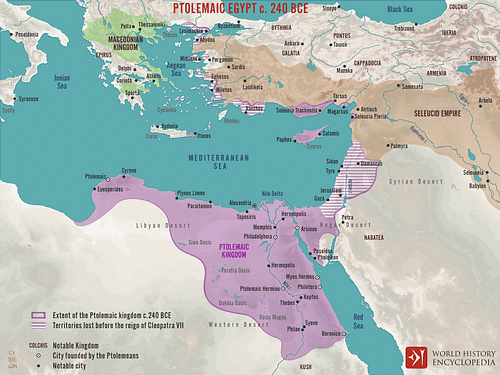

After the death of Cleomenes, Ptolemy I quickly and firmly began to establish himself in Egypt. His sole purpose was to make Egypt great again. Reluctantly, however, he became involved in the ongoing Wars of the Successors (the destructive battles between Alexander the Great's generals). While Ptolemy I did not intentionally seek territory outside Egypt, he would, however, take advantage of an occasion if it arose and he would occupy the island of Cyprus in c. 318 BCE. Another opportunity found him fighting a Spartan named Thribon who had seized the city of Cyrene on the North Africa coast. After a quick, decisive victory, he turned the fallen conqueror over to the city who promptly executed him. Unfortunately, Ptolemy could not avoid some involvement with the other commanders, and he gave refuge to Seleucus and later supported Rhodes against the invading forces of Demetrius the Besieger, son of Antigonus.

Still, there was his ongoing rivalry with Perdiccas. The hostility did not subside when Ptolemy stole Alexander's body as it was being transported to a newly built tomb in Macedon. As the king's chiliarch, Perdiccas had established himself securely after Alexander's death, always hoping to reunite the empire. He possessed the signet ring as well as the king's body, preparing to return it to Macedon. However, at Damascus the body inexplicably disappeared. Ptolemy I had stolen and taken the body to Memphis and then to Alexandria where the golden sarcophagus was displayed in the center of the city. Perdiccas, to say the least, was outraged. However, to those in Egypt the legitimacy of the Ptolemaic dynasty lay in its connection to the fallen king. Even in death, he played a major role in both the Egyptian and Ptolemaic imagination. The theft of Alexander was too much for Perdiccas. The long disagreement finally ended in war (322 – 321 BCE). He stepped up his military assault on the Ptolemaic pharaoh, but after three failed attempts to cross the Nile into Egypt and the loss of over two thousand soldiers, his army had had enough and executed him. There were few if any tears among the other commanders for Perdiccas had not been very popular.

Ptolemy II Philadelphus

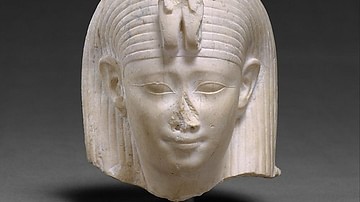

Ptolemy I died in 282 BCE, and as his successor he named his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus (Sister-loving) (308-246 BCE). The younger Ptolemy had served as co-regent with his father since 285 BCE. Ptolemy II married the daughter of the Thracian regent/king Lysimachus, Arsinoe I. For alliance purposes, after the death of his first wife, Lysimachus had chosen to marry Arsinoe II, the daughter of Ptolemy I and his mistress Berenice, around 300 BCE. It was a marriage he would regret. For reasons unknown – probably to secure the throne of Thrace for her own son – Arsinoe II convinced her husband to kill his oldest son (by his first marriage) and heir on the trumped-up charges of treason. The murder of the popular young commander caused an uproar among many of his fellow officers.

After the death of Lysimachus, Ptolemy married his sister (and the king's widow) Arsinoe II Philadelphus. Unlike many of his successors, Ptolemy II expanded Egypt with the reclaiming of Cyrene (the city had declared independence from Egypt) and acquisitions in Asia Minor and Syria. He fought two wars – the Syrian Wars – against Antiochus I and Antiochus II (260-252 BCE) and married his daughter Berenice to Antiochus II. Unfortunately, he also fought and failed in the Chremonidean War against Macedon (267-261 BCE). In Egypt, he established trading posts along the Red Sea, completed construction on the Pharos, and enlarged the library and museum. To honor his parents he established a new festival, the Ptolemaeia.

Syrian Wars

Apparently, Ptolemy II was one the last truly great pharaohs of Egypt. Many of those who followed failed to strengthen Egypt both internally and externally. Jealousy and in-fighting were common. Upon the death of his father in 246 BCE, Ptolemy III Euergetes (Benefactor) (284-221 BCE) came to the throne. He married Berenice II from the Greek city of Cyrene. Among their six children were Ptolemy IV and a princess also named Berenice.

The princess' sudden death brought about the Canopus Decree (238 BCE) which, among other proclamations, honored her as a goddess. One interesting suggestion made in the decree was for a new calendar, one that included 365 days with one additional day every four years, but it was not adopted. In 246 BCE Ptolemy III invaded Syria to support his sister's husband Antiochus II in the Third Syrian War against Seleucus II but only acquired towns in Syria and Asia Minor.

His successor and son Ptolemy IV Philopator (Father-loving) (244-205 BCE) came to the Egyptian throne in 221 BCE. Keeping with family tradition, he married his sister Arsinoe III in 217 BCE. He gained a small degree of success in the Fourth Syrian War (219-217 BCE) against Antiochus III. However, largely ineffective, his only other accomplishment was the building of the Sema, a tomb to honor both Alexander and the Ptolemies. Unfortunately, he and his wife were both murdered in a palace coup in 205 BCE.

Ptolemy V Epiphanes (Made-Manifest) (210-180 BCE) was the son of Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III and due to the sudden death of his parents inherited the throne as a small child. He married the Seleucid princess Cleopatra I in 193 BCE. Unfortunately, war and revolt by Seleucid and Macedonian kings with hopes to seize Egyptian lands followed his ascension. Following the Battle of Panium in 200 BCE Egypt lost valuable territory in the Aegean and Asia Minor, including Palestine. In 206 BCE dissidence arose in the Egyptian city of Thebes, and it would remain outside Ptolemaic control for twenty years.

Ptolemy V's successor Ptolemy VI Philometor (Mother-Loving) began his reign, like his father, as a small child, serving with his mother until her unexpected death in 176 BCE. Despite having serious troubles with his brother, the future Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II (Benefactor), he married his sister Cleopatra II and began his tumultuous reign. Egypt was invaded twice (169-164 BCE) by Antiochus IV; his army even approached the city of Alexandria. With the assistance of Rome, Ptolemy VI regained nominal control of Egypt, but his reign – ruling with his brother and wife – remained full of unrest. In 163 BCE his brother and he finally reached a compromise whereby Ptolemy VI acquired Egypt while Ptolemy VIII ruled Cyrene. In 145 BCE, Ptolemy VI died in battle in Syria.

Civil War

Little is known of the reign or person known as Ptolemy VII or if indeed he ever really reigned, but Ptolemy VIII, the younger brother of Ptolemy VI, stepped onto the throne in 145 BCE. In true Ptolemaic fashion, he married his brother's widow, Cleopatra II, only to replace her with her daughter, his niece, Cleopatra III. A civil war ravaged Egypt lasting from 132 to 124 BCE; it especially devastated the capital city of Alexandria, which happened to hate Ptolemy VIII. Actually, this was not uncommon for there was little love if ever between the city's citizens and the royal family. This intense loathing brought about extreme persecution and expulsion for the inhabitants of the city. Finally, an amnesty was reached in 118 BCE.

Ptolemy VIII was succeeded by his eldest son in 116 BCE. Ptolemy IX Soter II (Savior) (142-80 BCE) was also known as Lathyrus (Chickpea). Like many of his predecessors, he would marry two of his sisters, Cleopatra IV, mother of Berenice IV, and Cleopatra V Serene who gave him two sons. He ruled jointly with his mother Cleopatra III until 107 BCE when he fled to Cyprus after being overthrown by his brother. He regained the throne in 88 BCE and ruled until his death in 80 BCE.

The Rise of Rome

The next few pharaohs made little impact if any on Egypt, and for the first time, a rising power in the west made a major impact, Rome. Ptolemy X Alexander I (140-88 BCE) was the younger brother of Ptolemy IX and had served as governor of Cyprus until his mother brought him to Egypt in 107 BCE, replacing his brother. In 101 BCE he supposedly murdered his mother Cleopatra IV. He then married the daughter of Cleopatra V Serene (his niece), Berenice III. He left Egypt after being expelled in 88 BCE only to be lost at sea. He was succeeded briefly by his youngest son Ptolemy XI Alexander II (100-80 BCE). After awarding Egypt and Cyprus to Rome, Ptolemy XI was placed on the throne by the Roman general Cornelius Sulla and ruled jointly with his step-mother Cleopatra Berenice until he murdered her. Unfortunately, he was then himself murdered by the Alexandrians.

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos (also known as Auletes) was another son of Ptolemy IX succeeding Ptolemy XI in 80 BCE. He married his sister Cleopatra Tryphaena. Unfortunately, his close relationship with Rome caused him to be despised by the Alexandrians and expelled in 58 BCE. However, he regained the throne with the assistance of the Syrian governor Gabinius and was only able to remain through bribes and his ties to Rome as the Roman Senate actually distrusted him.

The next pharaoh, Ptolemy XIII (63-47 BCE), was the brother and husband of the infamous Cleopatra VII. His time on the throne was short-lived. He had joined unsuccessfully with his sister Arsinoe in a civil war, choosing to oppose both Julius Caesar and Cleopatra in a fight for the throne. Initially, he had expected to gain favor with Caesar when he killed the Roman general Pompey, who had sought refuge in Egypt and presented the severed head to Caesar. However, the Roman commander grew irate because he wanted to kill Pompey himself. Ptolemy XIII's army was defeated after an intense battle, and he drowned in the Nile River when his boat overturned. Arsinoe was taken to Rome in chains (later to be released).

Following Ptolemy XIII was another brother, Ptolemy XIV (59-44 BCE), who had served briefly as governor of Cyprus and later married his sister (on the wishes of Caesar), ruling until his abrupt death possibly caused by poisoning on the orders of his big sister.

The Last Ptolemaic Pharaoh Cleopatra

Lastly, the final pharaoh of Egypt was Cleopatra VII who is known to history as simply Cleopatra. She ruled Egypt for 22 years, controlling much of the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Like many of the women of her era, she was highly educated, being groomed for the throne by her father Ptolemy XII in the traditional Greek (Hellenistic) manner. She endeared herself to the Egyptian people, participating in many Egyptian festivals and ceremonies as well as being the only Ptolemy to learn the Egyptian language besides speaking Hebrew, Ethiopian, and other dialects.

To secure the throne after defeating her brothers and sister, she realized she had to remain friendly with Rome. Her relationship with Julius Caesar has been the subject of the dramatists and poets for centuries. With the death of Caesar and the balance of power in Rome in question, she sided, unfortunately, with the Roman general Mark Antony, only to lose it all at the Battle of Actium. Regrettably, she failed to find compassion in Octavian, the future Roman emperor Augustus, and committed suicide. Her son by Caesar, Caesarion (Ptolemy XV), was put to death by Octavian. Her other children, Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus were younger and were brought to Rome to be raised by Octavian's wife. As with the rest of the Mediterranean – described once as a Roman lake – Egypt submitted to Roman rule and the power of the Ptolemies ended.

Hellenization & Alexandria

One of the most significant features of Ptolemaic rule was its policy of Hellenization, integrating Greek language and culture into Egyptian daily life. There was no attempt to become assimilated into Egyptian civilization. One of Ptolemy I's first moves was to relocate the center of government from its traditional location at Memphis - it would remain the religious center - to the newly built city of Alexandria.

Alexandria had a more strategic location, much closer to both the Mediterranean Sea and Greece. Because of this move, Alexandria grew into more of a Greek rather than an Egyptian city. In fact, the Ptolemies would rarely leave the city and then only take a pleasure cruise down the Nile. As with much of the former Alexandrian empire, Greek would become the language of government and commerce.

Ptolemy I also established Alexandria as the intellectual center of the Mediterranean when he built a massive library and museum there. While the museum provided seating for quiet reflection, the library amassed a collection of thousands of papyrus scrolls, attracting men of philosophy, history, literature, and science from all over the Mediterranean for decades to come. Ptolemy I's advisor on the project was Demetrius of Phaleron, a graduate of Aristotle's Lyceum in Athens; the library truly became a center of Hellenistic culture. Unfortunately, the library and its contents were destroyed in a series of fires during its years under Roman control.

In the city's harbor, Ptolemy began the construction of the Pharos, a massive lighthouse (to be completed by his son Ptolemy II). The Lighthouse of Alexandria was an immense structure of three stories. Its beacon was visible for miles and was lit both day and night, eventually becoming one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. Aside from Alexandria, another city, less glamorous, was built in Upper Egypt: Ptolemais was founded as a center for the influx of newly arrived Greek residents.

While it may appear that Ptolemy I intended to transform Egypt into another Greece, in many ways he still respected the Egyptian people and recognized the importance of religion and tradition to their society. Both he and his successors supported the many local cults. To keep peace with the temple priests, he restored numerous religious objects stolen by the Persians. However, while the old Egyptian gods were respected – one did not want to anger the gods – two new cults arose: the first was dedicated to Alexander the Great, which for the Greek population served as a way to express their continued loyalty to the Ptolemies. A second cult, which never gained popularity, was devoted to the god of healing Serapis. Locally, the temple priests remained as a part of the ruling class – another test of their allegiance to the Ptolemies.

Lastly, while the capital may have been moved, the basic administrative structure was retained, although many of the Egyptian scribes had difficulty writing in Greek. Egypt had a closely controlled economy; much of the land was royal land and permission was needed to fell a tree or even to breed pigs. Record-keeping was important, all land was surveyed and livestock inventoried. Of course, since Egypt had an economy based on agriculture, taxes based on the census and land surveys were essential. Under Cleopatra VII there was a salt tax, a dike tax, and even a pasture tax. Fishermen even had to relinquish twenty-five percent of their catch.