The Protestant Reformation in the Netherlands was among the most violent and destructive of any region during the first 50 years of the movement, ultimately informing the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648), but causing massive destruction and death prior to that conflict through religious intolerance and the inability to compromise by either faction.

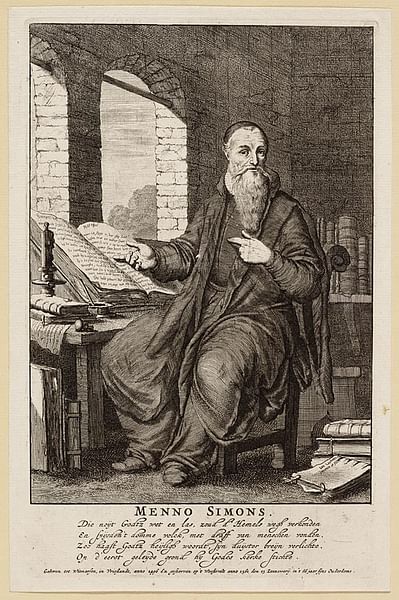

The Reformation first arrived in the Low Countries (Netherlands) around 1530 and was advanced through the evangelical efforts of Melchior Hoffman (l. c. 1495 to c. 1543), originally an adherent of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) before adopting the views of Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) and then aligning himself with the Anabaptists. Hoffman advocated for the slaughter of the 'godless' – defined as not only Catholics but any Protestant sect that believed differently – and was countered c. 1535 by another Anabaptist leader, Menno Simons (l. 1496-1561), and his message of non-violence.

These two factions – the Melchiorites and Mennonites – each with different visions of the Christian message, were only two of the many dissenting Protestant sects in the Low Countries c. 1530-1648, which also included those Anabaptists who did not adhere strictly to either, the Calvinists (followers of John Calvin, l. 1509-1564), the Remonstrants (who supported the Arminianism of Jacobus Arminius (l. 1560-1609), Zwinglians, and other splinter groups influenced by Luther, Andreas Karlstadt (l. 1486-1541), Thomas Müntzer (l.c. 1489-1525), Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551), and others.

The Netherlands was ruled by Spain under the Catholic King Philip II (r. 1556-1598), son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556), who continued and broadened his father's anti-Protestant policies. Charles V had introduced the Inquisition to the Netherlands, and Philip II gave inquisitors and local magistrates a free hand in identifying and destroying those defined as 'heretics'. These policies were further enforced by Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle (l. 1517-1586), who led the Inquisition until he was recalled in 1564, then by Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the 3rd Duke of Alba (l. 1507-1582) whose persecutions, along with high taxes and general discontent over Spanish rule, led to the Eighty Years' War.

After over one hundred years of violence, destruction, and death, largely in the name of the Christian religion, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) ended the war and established the Protestant and independent Dutch Republic of seven provinces in the north while the Southern Provinces remained Catholic and under the control of Spain. The years of violence, destruction, and death leading up to the Eighty Years' War differ from persecutions of Protestants elsewhere in severity, numbers killed, governmental policies encouraging the killings, and religious fanaticism on both sides.

Protestant Sects & the Edict of 1556

Martin Luther's 95 Theses began the Reformation after they were posted in 1517, but ten years later, Lutheranism still had no foothold in the Low Countries. Zwingli's teachings in Zürich, Switzerland inspired the establishment of the Anabaptists who were the first to make inroads into the Low Countries, owing primarily to their initial acceptance of differing views and their insistence on the imminent end of the world which all should prepare for. The apocalyptic preaching of Anabaptist ministers drew large numbers of converts fearing for the state of their souls at the Last Judgment.

Melchior Hoffman shared many of the beliefs of the Anabaptists and finally was baptized into the sect in 1530 in Strasbourg, afterwards arriving in the Low Countries and making converts to Anabaptism at Leeuwarden. Executions of Anabaptists in the Low Counties began at Leeuwarden in 1531. The iconoclasm of the Anabaptist Melchiorites resulted in the destruction of churches and Catholic statuary between 1531-1535, with many participants jailed or executed, and an estimated 30,000 Anabaptists suffering the same fate between 1537-1547. Hoffman himself was imprisoned during this time, dying in jail c. 1543, after his failed prediction of the Second Coming at Münster in 1533, which largely informed the Münster Rebellion (1533-1534) and the attendant loss of life there.

In 1535, Menno Simons, formally a Catholic priest turned Anabaptist, published a tract against the use of violence, especially by Christians against other Christians. Those who accepted his views then identified themselves as Mennonites at the same time that the Melchiorites had separated themselves from mainstream Anabaptists and others, following different leaders, followed suit. In 1555, Charles V, who had been trying to control and contain the rapidly splintering 'heresies' in the Low Countries through the Inquisition, turned the problem over to his son, who assumed control of the region before becoming king in 1556. One of Philip II of Spain's early decrees was a continuance of Charles V's "Edict of Blood" from 1550. Issued in 1556, it reads, in part:

No one shall print, write, copy, keep, conceal, sell, buy or give in churches, streets, or other places, any book or writing made by Martin Luther, John Oecolampadius, Huldrych Zwingli, Martin Bucer, John Calvin, or other heretics reprobated by the Holy Church…nor break, nor otherwise injure, the images of the holy virgin, or canonized saints, nor in his house hold conventicles, or illegal gatherings, or be present at any such in which the adherents of the above-mentioned heretics teach, baptize, and form conspiracies against the Holy Church and the general welfare.

Moreover, we forbid all lay persons to converse or dispute concerning the Holy Scriptures, openly or secretly, especially on any doubtful or difficult matter, or to read, teach, or expound the Scriptures unless they have duly studied theology and been approved by some renowned university…or to preach secretly, or openly, or to entertain any of the opinions of the above-mentioned heretics on pain, should anyone be found to have contravened any of the points above mentioned, as perturbators of our state and of the general quiet, to be punished in the following manner…

That such perturbators of the general quiet are to be executed, to wit: the men with the sword and the women to be buried alive, if they do not persist in their errors; if they do persist in them, then they are to be executed with fire; all their property in both cases being confiscated to the crown…

We forbid all persons to lodge, entertain, furnish with food, fire, or clothing, or otherwise to favor with anyone holden or notoriously suspected of being a heretic…and anyone failing to denounce any such we ordain shall be liable to the above-mentioned punishments…

All who know of any person tainted with heresy are required to denounce and give them up to all judges, officers of the bishops, or others having authority on the premises, on pain of being punished according to the pleasure of the judge. Likewise, all shall be obliged, who know of any place where such heretics keep themselves, to declare them to the authorities, on pain of being held as accomplices, and punished as such heretics themselves would be if apprehended…

The informer, in case of conviction of the alleged heretic, should be entitled to one half of the property of the accused, if not more than one hundred pounds Flemish; if more, then ten percent of all such excess…If any man being present at any secret conventicle, shall afterwards come forward and betray his fellow members of the congregation, he shall receive full pardon. (Lindberg; Source 11.2; p. 196-197)

The Edict of 1556, as it clearly states, addressed any Protestant sect, but primarily Calvinism, established in the Low Countries in the 1540s, spreading quickly and gaining enormous support. The Calvinists had arrived in large numbers following the persecutions in France by King Francis I of France (Francois I, r. 1515-1547) enacted in 1534 after the Affair of the Placards, during which Calvinists posted anti-Catholic messages throughout France. More would arrive in the years leading up to and during the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) and would form powerful political blocs. The Mennonites were also a target as their pacifist views and rejection of participation in public affairs were seen as a threat to the state, which placed a bounty on Menno's head; he was never caught, however, and died of natural causes in 1561.

The edict, posted publicly on placards throughout the region in August 1556, encouraged neighbor to betray neighbor not only in hope of personal gain but out of safety concerns for oneself and one's family; if one betrayed a heretic to the Inquisition, one was less likely to be suspected of heresy oneself. It did nothing, however, to stop the spread of Protestant sects (who issued their Belgic Confession of Faith to Philip II in 1562) or the proliferation of street preachers, who often drew large crowds in urban centers, fields, farms, and marketplaces.

Hedge Preaching & Persecution

These open-air religious services, led largely by Calvinists, came to be known as hagenpreken (sing. hagenpreek, "hedge sermon" or, more commonly, "hedge preaching"). In a report to the then-governor Margaret of Parma (l. 1522-1586, illegitimate daughter of Charles V), in 1566, an official reported:

I am forced to tell Your Highness that last night there were two more preaching. The largest had 4,000 people…on the road to Tournai and was led by a preacher named (or so I believe) Cornille de La Zenne, a blacksmith's son from Roubaix. His beliefs have made him a fugitive from justice for quite a while now…We fear that as soon as the harvest is in and the barns full (in two- or three-weeks' time) they will take over the countryside and starve the cities. Thus, they will use poverty to force people to follow them. I think, therefore, that orders should be given soon to find some way to stop these meetings. I have been told by some that certain French gentlemen are ready to aid the treasonous rebellion when it comes. I am hopeful that we can rely on the nobles of the Low Countries.

On Sunday 7 July 1566 – despite the rules – there were more sermons, this time at noon in Stallendriesche. Thousands of people from the city and the country came along including many of the common people who had little training in the Bible and the Church Fathers. The preachers said that the truth was being presented and the Gospel preached correctly for the first time. To prove this, the preachers quoted the Bible loudly and forcefully. They encouraged the audience to check what they said against what was in their Bibles to see that they were preaching truthfully. (Lindberg; Source 11.5, p. 199)

This same year, the Great Iconoclasm (Beeldenstorm, "statue storm") was unleashed throughout the summer during which Calvinist mobs destroyed Catholic churches and iconography. Margaret of Parma tried to address the chaos diplomatically and brokered an accord with Calvinist leaders granting them freedom of religion in exchange for their promise to allow Catholics the same. These leaders had no control over the many Protestant sects, however, all of whom disagreed in one way or another with each other and only found common ground in their hatred for the Catholic Church which, according to their beliefs, was satanic and an enemy of the True Faith.

Cardinal Granvelle had been recalled by this time, and so Margaret turned the problem over to the stadtholder (administrator) William the Silent (l. 1533-1584, also known as William of Orange), who, though Catholic at this time, had been raised Lutheran and was sympathetic to the Protestant cause. William's epithet of "the Silent" had nothing to do with a speech impediment but was given because of his ability to keep his thoughts to himself, especially in the presence of opposing views. Having been both Protestant and Catholic, he was a strong advocate of freedom of religion.

Before William could take the matter in hand, however, Philip II had already ordered the Duke of Alba to the region. Alba's persecution of the Calvinists was immediate and so harsh that Margaret of Parma resigned as governor, wanting no further part in the atrocities. Alba's religious persecutions, furthering the agenda of the Inquisition, along with Philip II's Edict of 1555, high taxes to pay for foreign wars, and seeming neglect of the region by Spain in anything other than the slaughter of Calvinists, combined to ignite the Eighty Years' War in 1568.

Conclusion

William the Silent broke with Spain and Catholicism to command the Protestant forces until his assassination in 1584 during the same approximate period that the Duke of Alba led the Catholic armies of Spain with citizens of the Low Countries supporting one or the other. The Dutch Protestants and Catholics united for a brief interim against the Spanish forces when the latter turned to sacking cities but, for the most part, continued killing each other in the name of their respective religious visions. The States-General of the Low Countries had already rejected Philip II's reign prior to the war's outbreak, but in 1581, it was made official through the Act of Abjuration, which reads in part:

Let all men know that, in consideration of the matters considered above and under pressure of utmost necessity, we have declared and declare hereby by a common accord, decision, and consent, the King of Spain forfeit his lordship, principality, jurisdiction, and inheritance of the countries, and that we have determined not to recognize him hereafter in any matter concerning the principality, supremacy, jurisdiction or domain of these Low Countries, nor to use or permit others to use his name as Sovereign Lord over them after this time. (Lindberg; Source 11.13, p. 203)

The States-General, at the urging of William the Silent, offered the crown to the French noble Francis, Duke of Anjou and Alençon (l. 1555-1584), who accepted but allowed his greed to lead him to invade Antwerp in 1583, where he was defeated, and then he went back to France. The crown was also offered to Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603), who declined but offered an English protectorate including military aid. Throughout this same period, religious divisions continued resulting in more deaths including the assassination of William the Silent in 1584 by the Catholic zealot Balthasar Gerard, responding to a bounty Philip II had placed on William's head.

As the war raged on, and more people died, Philip II refused to recognize the Act of Abjuration or any appeals to compromise or for religious tolerance, responding to the latter suggestion in a writ in 1585:

In spite of everything, I would regret very much to see this toleration conceded without limits. The first step [for Holland and Zeeland] must be to admit and maintain the exercise of the Catholic religion alone and to subject themselves to the Roman Church, without allowing or permitting, in any agreement the exercise of any other faith whatever in any town, farm, or special place set aside in the fields or inside a village…And in this there is to be no exception, no change, no concession by any treaty of freedom of conscience…They are to embrace the Roman Catholic faith and the exercise of that alone is to be permitted. (Lindberg; Source 11.14, p. 204)

Philip II was hardly the sole source of dissension and conflict, however. Even before Dutch resentment of Spanish rule erupted in war, people were killing each other in the Low Countries over differences in religion. During the period of the Eighty Years' War known as the Twelve Years' Truce (1609-1621) when hostilities between Spain and the Low Countries ceased, Protestants fought each other over religion with different factions claiming the others had betrayed Calvin's vision and were not 'true Christians'. Anabaptists rejected the strict pacifism of the Mennonites, Calvinists rejected the Anabaptists, and both rejected the Lutherans.

Although the policies the Spanish kings decreed were harsh and certainly contributed to the Eighty Years' War, Charles V, Philip II, and his successors Philip III (r. 1598-1621) and Philip IV (r. 1621-1665) were adhering to a Catholic tenet articulated early in the Protestant Reformation against the claims of Luther and which became central to the Catholic Counter-Reformation (1545 - c. 1700) later: that if there is no single authority to determine truth from false belief in religion, then anyone can claim their particular truth as ultimate truth without reference to an objective standard.

This claim by the Church proved prophetic within the first five years of the publication of Luther's 95 Theses as Protestant sects broke from his vision to form their own. This paradigm was apparent in Germany as early as 1521 and then repeated itself elsewhere afterward, but perhaps nowhere with more devastating loss of life and property than in the Netherlands in the period leading up to and through the Eighty Years' War.