The art of the Renaissance period in Europe (1400-1600 CE) includes some of the most recognisable and best-loved paintings and sculptures in the world. Masters were often skilled in both painting and sculpture, and by studying the art of antiquity and adding their theoretical knowledge of mathematical perspective and new painting techniques, they produced truly unique works of art. Realism, detail, drama, and subtle layers of meaning became features of religious and secular art. Now, artists finally broke free from their old craftworker status and achieved a new position as vital contributors to the culture and prestige of the societies in which they lived.

Defining features of Renaissance art include:

- an interest in capturing the essential elements of classical art, particularly the form and proportions of the human body.

- an interest in the history of contemporary art and forging a continuous path of development.

- a blending of pagan and religious iconography but with humanity as its focus.

- a tendency towards monumentality and dramatic postures.

- an interest in creating an emotional response from the viewer.

- the development of precise mathematical perspective.

- an interest in hyperrealistic and detailed portraits, scenes, and landscapes.

- an interest in the use of bright colours, shade, and capturing the effects of light.

- the development in use of oil paints and fine prints.

- the use of subtle shapes and everyday objects to give extra meaning.

- an increase in the prestige of artists as superior craftworkers who combined intellectual studies with practical skills.

Medieval Origins

It used to be thought that Renaissance art sprang out of nowhere in a miraculous rebirth of ideas and talent but investigation by modern historians has revealed that many elements of Renaissance art were being experimented with in the 14th century CE. Artists like Giotto (d. 1337 CE) were keen to make their paintings more realistic and so they used foreshortening to give a sense of depth to a scene. Giotto's use of foreshortening, light and shadows, emotion, and dynamic choice of scenes can be best seen in his religious frescos in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua (c. 1315 CE). These techniques, and the artist's success at making characters come alive, would be hugely influential on later artists. For this reason, Giotto is often referred to as the 'first Renaissance painter' even if he lived before the Renaissance proper.

Wealthy patrons were the driving force behind Renaissance art in a period when the vast majority of artistic works were made on commission. Churches were the usual beneficiaries of this system in the first part of the Renaissance. Painted panels for altarpieces and frescos were the most common form of artistic decoration, often showing the sacra conversazione, that is the Virgin and Child surrounded by saints and well-wishers. Monumental altarpieces several metres high were often elaborately framed to mimic contemporary developments in architecture. The most famous altarpiece of all is the 1432 CE Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441 CE). Early Renaissance subjects, then, are very similar to those popular through the Middle Ages.

Private patrons such as Popes, Holy Roman Emperors, kings, and dukes all saw the benefit of beautifying their cities and palaces, but they were also very interested in gaining a reputation for piety and a knowledge of the arts and history. Once a patron found an artist they liked, they often employed them long-term as their official court artist, setting them all kinds of tasks from portraits to livery design. Patrons were paying and so they often made specific requests on the details of a piece of art. Further, although an artist could use their skills and imagination, they did have to remain within the bounds of convention in that figures in their work had to be recognised for who they were. It was, for example, no good making a fresco of a saint's life if nobody recognised who that saint was. For this reason, the evolution in art was relatively slow, but as some artists gained great fame, so they could develop new ideas in art and make it distinct from what had gone before.

The Classical Revival

A defining feature of the Renaissance period was the re-interest in the ancient world of Greece and Rome. As part of what we now call Renaissance humanism, classical literature, architecture, and art were all consulted to extract ideas that could be transformed for the contemporary world. Lorenzo de Medici (1449-1492 CE), head of the great Florentine family, was a notable patron, and his collection of ancient artworks was a point of study for many artists. Young artists, training in the workshops of established masters, also had access to ancient art there or at least reproduction drawings.

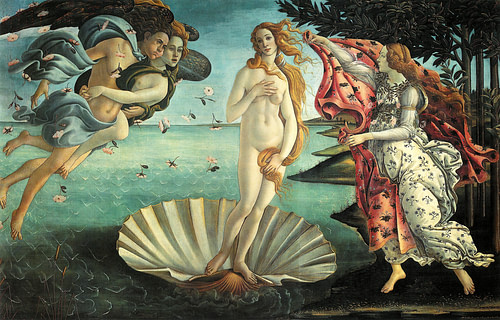

Artists directly imitated classical artworks or parts of them within their own works. In 1496 CE, for example, Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) sculpted the Sleeping Cupid (now lost) which he purposely aged to make it appear an authentic ancient work. Another recreation of antiquity, this time an entirely imaginary one, is The School of Athens fresco by Raphael (1483-1520 CE). Completed in 1511 CE and located in the Vatican, this fresco shows all the major thinkers from the ancient world. Common images from classical mythology were especially popular. These were again reimagined and, in some cases, they have even overtaken ancient art in our minds when we think of certain subjects. The Birth of Venus (c. 1484 CE, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) by Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510 CE), is a case in point. Finally, the depiction of ancient architecture and ruins was a particular favourite of many Renaissance artists to give background atmosphere to both their mythological and religious works.

The Increased Status of Artists

Another new development was the interest in reconstructing the history of art and cataloguing who exactly were the great artists and why. The most famous scholar to compile such a history was Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574 CE) in his The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors (1550 CE, revised 1568 CE). The history is a monumental record of Renaissance artists, their works, and the anecdotal stories associated with them, and so Vasari is considered one of the pioneers of art history. Artists also benefited from having specific biographies written about their lives and works, even when they were still alive such as the 1553 CE Life of Michelangelo, written by Ascanio Condivi (1525-1574 CE). Artists also wrote texts on techniques for the benefit of others, the earliest being the Commentaries by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455 CE), written about 1450 CE. As the Commentaries includes details of Ghiberti's own life and works, it is also the first autobiography by a European artist.

This interest in Renaissance artists, their private lives, and how they came to create masterpieces reflects the elevated status they now enjoyed. Artists were still seen as craftsmen like cobblers and carpenters, and they were compelled to join a trade guild. This began to change during the Renaissance. Artists were obviously different from other artisans because they could acquire widespread fame for their works and create a sense of civic pride from their fellow citizens. However, it was the intellectual endeavours of painters like Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE) and Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528 CE) that finally elevated painters to the status of 'artists', a term previously restricted to those who studied the traditional liberal arts such as Latin and rhetoric. Artists took a keen interest in studying the history of art, what was going on in the art world elsewhere, wrote treatises on their craft, and made experiments in mathematical perspective. All of these things elevated art to a science.

Another defining feature of Renaissance artists, especially those belonging to the High Renaissance (1490-1527 CE) is their extraordinary ability in a variety of media. Figures like Michelangelo and Leonardo were as accomplished painters as they were sculptors, and both, like many other masters, turned their hand to architecture, too. Such successful masters ran large workshops and these were training grounds for the next generation of artists.

A greater confidence in their skills, knowledge, and contribution to culture in general can be seen in the increasing number of artists who painted self-portraits. Another symptom was the frequent signing of artworks, sometimes in very prominent parts of the picture (even if the assistants in a master's workshop frequently finished off works).

A Gallery of 50 Renaissance Paintings

Painting & New Techniques

Renaissance painters were versatile and often experimented but, generally, as the Renaissance wore one, they used the fresco technique for walls, tempera for panels, and oil for panels or canvas. Fresco - painting on a wet plaster background - and tempera - using pigments mixed with egg yolk - were both techniques employed long before the Renaissance period. Experiments were, however, made using oil paints (pigments mixed with linseed or walnut oil) which gave richer colours, a wider range of tones, and more depth than traditional colours. Oils permitted more details to be shown in the painting and allowed brush strokes to become a visual effect. By the end of the 15th century CE, then, most major artists were using oils when working at an easel, not tempera. The disadvantage of oils was that they quickly deteriorated if used on walls instead of true fresco.

There were different painting styles and techniques depending on location. For example, the colore (or colorito) technique was prevalent in Venice (where contrasting colours were used to effect and define a harmonious composition) while disegno was preferred in Florence (where line drawing of form took precedence). Other techniques perfected by Renaissance artists include chiaroscuro (the contrasting use of light and shade) and sfumato (the transition of lighter into darker colours).

The painting's subject was another opportunity for experimentation. Painting figures with dramatic poses became a Renaissance fashion, best seen in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome (1512 CE). A tremendous sense of movement is created by the artist's use of contrapposto, that is the asymmetry between the upper and lower body of the figures, a technique used by Leonardo and many others. Another idea was to create shapes in a scene, especially triangles. The aim of this was to create a harmonious composition and give extra depth, as can be seen in Leonardo's Last Supper mural in Milan's Santa Maria delle Grazie (c. 1498 CE) or the Galatea by Raphael (c. 1513 CE, Villa Farnesina, Rome).

Artists strove for an ever-greater sense of reality in their paintings, and this could be done by reproducing the perspective one would expect to see in a three-dimensional view. Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506 CE) used techniques of foreshortening just as Giotto had done. See his The Agony in the Garden (c. 1460 CE, National Gallery, London). Mantegna was also keen on painting his scenes as if one were looking at them from below, another trick which gave his work depth. Sometimes depth was achieved in the middle ground of the painting while figures dominated the foreground, bringing them closer to the viewer. It was a technique innovated by Pietro Perugino (c. 1450-1523 CE) and can be best seen in the Marriage of the Virgin (c. 1504 CE, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan) by Raphael, once a pupil of Perugino.

Meanwhile, painters like Piero della Francesca (c. 1420-1492 CE) went further and used precise mathematical principles of perspective, as can be seen in his Flagellation of Christ, (c. 1455 CE, National Gallery of Marche, Urbino). Some critics felt that some artists went too far in their use of perspective and so the original sense of their painting was lost; Paolo Uccello (1397-1475 CE) was a particular victim of this claim. Uccello's The Hunt (c. 1460 CE, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) is certainly an audacious painting with its panoramic view of a symmetrical forest receding into an ever-darker background while the foreground is dominated by the hunters and their hounds, all converging towards a distant central point.

Another step towards a greater reality was to ensure the scene had a single light source which provides matching areas of shadow in all elements of the painting. See, for example, the 1480 CE Ecstasy of Saint Francis (Frick Collection, New York) by Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430-1516 CE). Artists even began to play tricks on the viewer such as the mirror in Jan van Eyck's The Arnolfini Wedding portrait (1434 CE, National Gallery, London) which shows reflections of figures who must be standing next to the viewer. All of these techniques had the additional advantage of creating a 'wow factor' from viewers not used to seeing such innovations.

Renaissance painters wanted to add another level of meaning to their work than just the visual first impression. Mythological scenes were often packed with symbolism, meant to sort out the well-educated viewer from the less so. Titian (c. 1487-1576 CE) even described his mythological paintings as a form of poetry, what he called poesia, such was the density of classical references within them. See, for example, his Bacchus and Ariadne (c. 1523 CE, National Gallery, London).

Portraiture was yet another area where Renaissance artists excelled. The most famous example is Leonardo's Mona Lisa (c. 1506 CE, Louvre, Paris), which shows an unidentified woman. Leonardo has not only painted a likeness but also captured the mood of the sitter. Contours, perspective, and gradations in colour are all combined to give the image life. Further, the casual posture and three-quarter view of the lady are another hint at movement. This painting was hugely influential on portraits thereafter. Another development was the use of everyday objects in portraits to hint at the sitter's character, beliefs, and interests. The Netherlandish painters were particular masters at realistic portraits, and their ideas spread to Italy where they can be seen in the work of, for example, Piero della Francesca, notably his painting of Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino (c. 1470 CE, Uffizi, Florence).

Sculpture & Breaking the Classical Mould

While many religious subjects remained popular in sculpture like the Pietà - the Virgin Mary mourning over the body of Jesus Christ - conventional iconography soon gave way to more innovative treatments. Donatello (c. 1386-1466 CE), for example, experimented with sacrificing technique and finish to capture the emotion of a figure, a strategy best seen in his wooden Mary Magdalene (c. 1446 CE, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence).

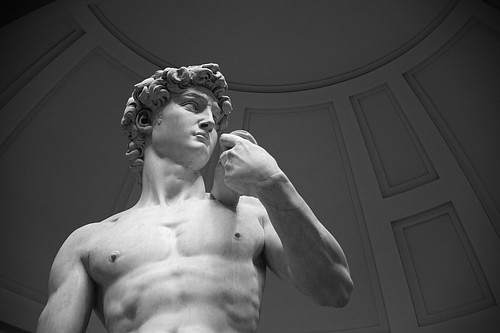

The classical revival saw sculptors create their own versions of ancient figures in wood, stone, and bronze. Most famous of all is Michelangelo's David (1504 CE, Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence). Representing the biblical king who, in his youth, famously killed the giant Goliath, the marble figure is much larger than life-size, around 5.20 metres (17 feet) tall. It reminds of colossal statues of Hercules from antiquity, but the tension of the figure and his thoroughly determined face are Renaissance inventions.

Donatello produced his version of David in bronze (1420s or 1440s CE, Bargello, Florence) and this work was another dramatic departure from ancient sculpture. The posture creates a sensuous figure that could not have been produced in antiquity. Both Michelangelo's and Donatello's David remind of the close link between art and function during the Renaissance. David appeared on the official seal of Florence, and as the slayer of Goliath, it was a timely reminder of the Florentines' struggles against the rival city of Milan.

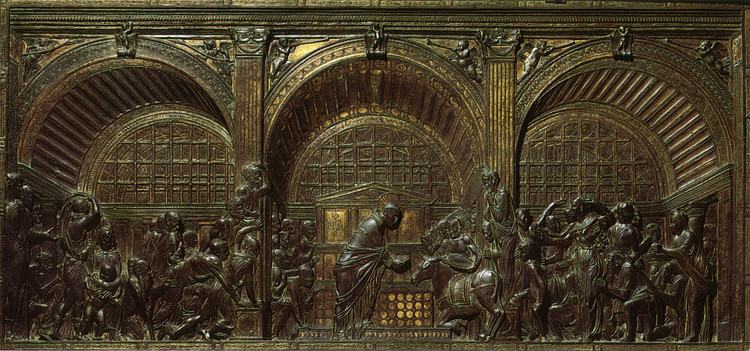

A related art to sculpture was engraving. Donatello was again involved here, producing superb low relief bronze panels for the baptistery of Sienna and several Florentine churches. The technique of carving a scene with a shallow depth yet still achieving a sense of perspective was known as 'flattened relief' or rilievo schiacciato. A very different technique was to create metal panels with figures so high in relief they are almost in the round. The most famous example of this technique is Lorenzo Ghiberti's 'Gates of Paradise', the doors for Florence's Baptistery of San Giovanni (completed in 1452 CE). The gilded panels attached to the doors show biblical scenes and even a bust of Ghiberti himself.

From 1420 CE, prints made from woodcuts were popular, but it was the development of engraving copper plates from the 1470s CE that really saw prints become a true art form. Copper plates gave a much greater precision and detail. Mantegna and Dürer were two notable experts at this, and their engravings became highly collectible. The most successful printer was Marcantonio Raimondi (1480-1534 CE), and his prints of fine art helped spread ideas to northern Europe and vice-versa.

The Legacy of Renaissance Art

Collecting art became a hobby of the wealthy, but as the middle classes became richer, so, too, they could acquire art, albeit not quite so great. Workshops like the ones run by Ghiberti began not exactly to mass-produce art but to at least employ standardised elements taken from an existing catalogue. In short, art was no longer restricted to the wealthy, and for those still unable to afford originals, they could always buy prints. Prints also spread artists' reputations far and wide. Thanks to the expansion of the art market, masters were now free to produce art as they thought it should be, not as a patron thought.

Renaissance art was continuously evolving. Mannerism, for example, is a vague term which initially referred to the oddly different art which came after the High Renaissance. Mannerism then acquired a more positive meaning - stylishness, ambiguity of message, contrast, and generally playing with the techniques and standardisations earlier Renaissance artists had set. See, for example, the 1548 CE Miracle of Saint Mark Rescuing a Slave by Tintoretto (c. 1518-1594 CE, Academia, Venice). From Mannerism would come the next major style in European art, the highly decorative Baroque, which took the rich colours, fine details, and energetic poses of Renaissance art to a new extreme of overwhelming drama and decoration.