Calligraphy established itself as the most important ancient Chinese art form alongside painting, first coming to the fore during the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE). All educated men and some court women were expected to be proficient at it, an expectation which remained well into modern times. Far more than mere writing, good calligraphy exhibited an exquisite brush control and attention to composition, but the actual manner of writing was also important with rapid, spontaneous strokes being the ideal. The brushwork of calligraphy, its philosophy, and materials would influence Chinese painting styles, especially landscape painting, and many of the ancient scripts are still imitated today in modern Chinese writing.

Materials

The highly flexible brushes used in calligraphy were made from animal hair (or more rarely a feather) cut to a tapering end and tied to a bamboo or wood handle. The ink used was made by the writer himself by rubbing a dried cake of animal or vegetable matter mixed with minerals and glue against a wet stone. Wood, bamboo, silk (from c. 300 BCE), and then paper (from c. 100 CE) were the most common writing surfaces, but calligraphy could also appear on such everyday objects as fans, screens, and banners. The best material was paper, though, and the invention of finer quality paper - credited to Cai Lun in 105 CE - helped the development of more artistic styles of calligraphy because its absorbency captured every nuance of the brushstroke.

Methods of Application

A connoisseurship quickly developed, and calligraphy became one of the six classic and ancient arts alongside ritual, music, archery, charioteering, and numbers. Accomplished Chinese calligraphers were expected to use varying thicknesses of brushstroke, their subtle angles, and their fluid connection to each other - all precisely arranged in imaginary spaces on the page - to create an aesthetically pleasing whole.

The historian R. Dawson gives the following description of the attraction of calligraphy created with an expert brush compared to the printed version:

The printed characters are like figures in a Victorian photograph, standing stiffly to attention; but the brush-written ones dance down the pages with the grace and vitality of the ballet. The beautiful shapes of Chinese calligraphy were in fact compared with natural beauties, and every stroke was thought to be inspired by a natural object and to have the energy of a living thing. Consequently Chinese calligraphers sought inspiration by watching natural phenomena. The most famous of all, Wang Xizhi, was fond of watching geese because the graceful and easy movement of their necks reminded him of wielding the brush, and the monk Huai-su was said to have appreciated the infinite variety possible in the cursive style of calligraphy known as grass-script by observing summer clouds wafted by the wind. (201-202)

Calligraphy Scripts

There were five main scripts in ancient Chinese calligraphy:

- Seal script (zhuan shu) - in use from c. 1200 BCE

- Clerical script (li shu) - from c. 200 BCE

- Regular script (kai shu, zhen shu or zheng shu) - from c. 200-400 CE

- Cursive script (xing shu) - from the 4th century CE

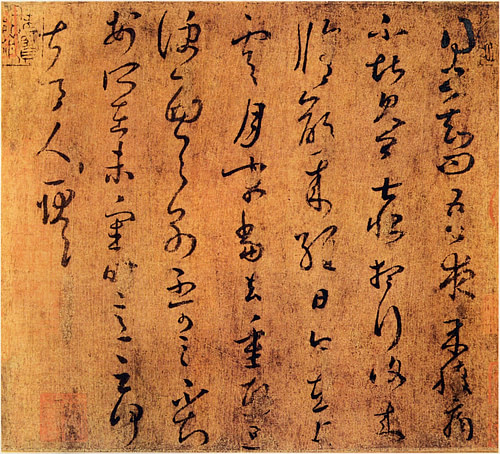

- Drafting script - (cao shu) - from the 7th century CE

Seal script, as its name suggests, was a formal style used for seals and other official documents because it has strokes of an even thickness and fewer direction changes, which made it easier for carvers to reproduce. Clerical script with its heavy stroke endings was also formal and reserved for record keeping by clerks and officials. Later, it became the common script for inscriptions. Both Seal and Clerical script were revived as artistic scripts in the 17th and 18th centuries CE. Regular script was the standard form for printing and remains the most commonly used today. The more flamboyant Cursive script was the most popular choice for artistic expression and used too in the notes added to paintings. Finally, Drafting script, sometimes also called Grass script, was so called because it was the quickest to produce and 'wildest' in that the artist stretched convention to its limits so that some characters become difficult to recognise immediately.

Despite these broad types, each calligrapher's writing style was, of course, his or her own. A calligrapher might aim for precision over spontaneity, prefer flamboyance to grace or concentrate on the spaces left blank within the composition. Besides aesthetic results writing was also judged for other purposes, as the historian M. Dillon here explains:

As a person's writing was regarded as a clue to temperament, moral worth, and learning, emperors of the Tang and Song dynasties often selected their ministers on the basis of the quality of their calligraphy…The life of the calligraphic tradition was sustained by the notion that calligraphy could convey the spontaneous feelings of the truly perceptive individual through an outflowing of spirit at a particular instant. (37)

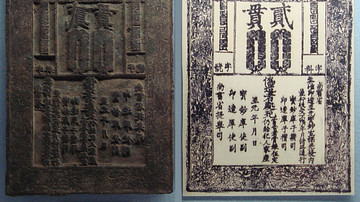

Famous Calligraphers

Just like in any other art, the most gifted practitioners of calligraphy became famous for their work and their scripts were copied and used in such innovations as printed books. The most revered of all Chinese calligraphers, as mentioned already, was Wang Xizhi (c. 303 - c. 365 CE), although he was a student of Lady Wei (272-349 CE). No examples of either figure's writing survive, except possibly in extant copies of Xizhi's. Wang Xizhi's son, Wang Xianzhi (344-388 CE), was another famous practitioner, the pair often referred to as 'the two Wangs'. Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322 CE) was another celebrated calligrapher who produced such precise characters placed neatly into square boxes on his paper that printers used his script for their own type blocks.

Examples of the scripts and styles created by these masters were often copied onto wood or stone to preserve them and from which ink rubbings (bei) were made. Thus, the paper copies could be distributed and the scripts could be imitated by lesser calligraphers everywhere. Such copies were also useful to emperors who wished to promote one style over another during their reign, and they have become an invaluable record of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy which continues to be consulted and imitated today.

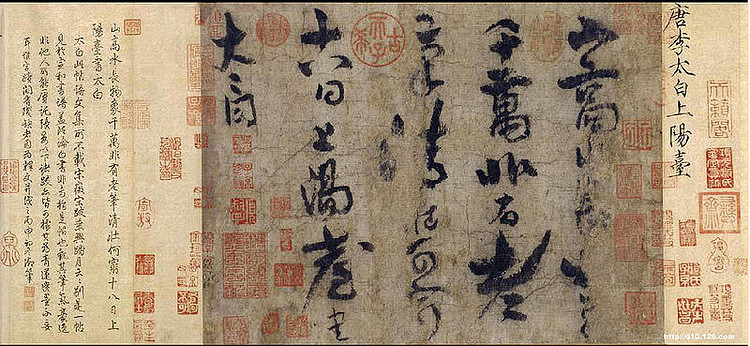

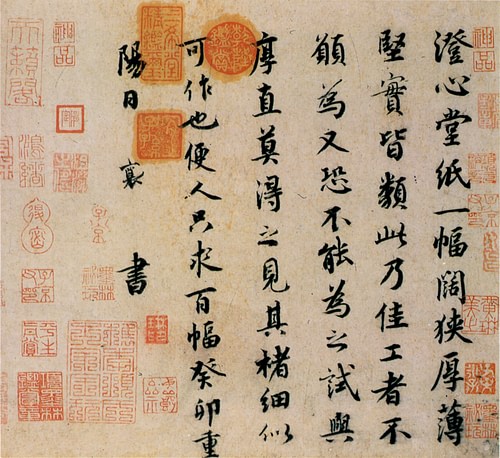

Examples of famous calligraphy survive in the form of letters, introductions to books, pieces of prose, religious texts, notes made on paintings, and engraved stele, tombstones and tablets, where the stonemason faithfully copied the work of a noted calligrapher. Examples of fine calligraphy by famous writers were even collected in ancient times, especially in the libraries of emperors or even buried with them in their tombs. So valued were these pieces that forgeries were made and sold as genuine to collectors. As another indicator of the value put on examples of calligraphy by great past masters, the actual meaning of the text is often irrelevant to prices and collectibility. There are many scraps (tie) which may be very old and highly valued but are, in fact, merely comments on the weather or a note for a gift of oranges.

Influence on Painting

The techniques and conventions of writing would influence painting where critics looked for the artist's forceful use of brushstrokes, their spontaneity, and their variation to produce the illusion of depth. Another influence of calligraphy skills on painting was the importance given to composition and the use of blank space. Finally, calligraphy remained so important that it even appeared on paintings to describe and explain what the viewer was seeing, indicate the title (although by no means all paintings were given a title by the original artist) or record the place it was created and the person it was intended for. Eventually, such notes and even poems became an integral part of the overall composition and an inseparable part of the painting itself.

There was a fashion, too, for adding more inscriptions by subsequent owners and collectors, even adding extra portions of silk or paper to the original piece to accommodate them. From the 7th century CE, owners frequently added their own seal in red ink, for example, and if a piece changed hands, then the new owner would add their seal so that the history of the work's ownership can sometimes be traced back hundreds of years. Chinese paintings, it seems, were meant to be perpetually handled and embellished with fine calligraphy.