Richard Strauss (1864-1949) was a German conductor and composer of both innovative late-Romantic and Modernist music. He is best known for his symphonic poems and operas like Salome and Elektra, both of which caused a sensation. Strauss gained a whole new generation of admirers when his Also sprach Zarathustra was used in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Early Life

Richard Strauss was born in Munich, Germany, on 11 June 1864. Richard's father Franz-Joseph was the principal horn player in the court orchestra of Munich, and his mother, Josephine Pschorr, was from a Munich family which owned a successful brewery business (the Pschorr brand still exists today). Richard inherited his father's musical talent and more, since by the age of four he could play the piano and by the age of eight the violin, too. He composed from age six. With his mother's money and father's connections in the music business, Richard was soon able to publish some of his own compositions, which included songs, sonatas, and symphonies. Richard, at the same time as developing his musicianship, studied philosophy and the history of art at the University of Munich. By his early 20s, he was already demonstrating "the paradoxical mixture of skilful economy and provocative lavishness that became the hallmark of his later style" (Sadie, 299).

Later, as a conductor, Strauss was not a particular fan of woodwind instruments, he once said, "If you can hear them at all, they are too strong" (Wade-Matthews, 142). In contrast, as a composer, he used them often, starting with his first major work the Serenade for wind instruments. Initially extravagant on the podium, Strauss' mature conducting style was particular, especially regarding his own compositions when the "critics could not get over the flamboyance of the music contrasted with the restraint of his gestures" (Schonberg, 486).

In the early 1880s, Strauss wrote his Suite in B flat, First Horn Concerto, a cello sonata, and a number of songs. His Second Symphony was given its premiere in New York. In 1885, the composer secured the position of assistant to the famed conductor Hans von Bülow (1830-1894). The position took Strauss to Meiningen in central Germany, and it turned out to be a great one for the young composer, since within a month von Bülow stepped back and Strauss became the main conductor of the well-respected Meiningen orchestra.

Romanticism & Symphonic Poems

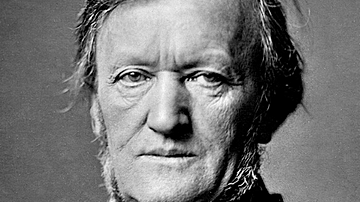

In 1886, Strauss took up a conducting post at the Munich court opera, a position he held for three years. Strauss had been an admirer of the operas of Richard Wagner (1813-1883) and of his fellow composer's ideas of Gesamtkunstwerk, that is, creating a 'total' artwork which seamlessly combined poetry, drama, and music. It was not opera that Strauss focussed on, though, but the tone poem (the term Strauss preferred) or symphonic poem, a format which has orchestral music that is inspired by a single idea taken from literature, art, or nature. Strauss' first symphonic poem was Aus Italien, composed while he was in Italy in 1886.

Strauss' star was rising, and he was appointed the assistant conductor at the Weimar court in 1889. He also found time to compose through the 1890s, notably the symphonic poems Macbeth, Don Juan (a runaway success), and Don Quixote amongst many others. Thus Spoke Zarathustra was another success in 1896, and it caught the public imagination in the next century when it featured in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Although he adheres to classical forms in his symphonic poems, "in the best of them there is a humour and sense of slightly ironic detachment which shows Strauss moving away from the romantic seriousness of his predecessors" (Arnold, 1756). These symphonic poems made Strauss internationally famous, and their innovative style meant that "an aura of sensation surrounded the slim, tall man and his outrageous music" (Schonberg, 485). Ironically, though, the symphonic poem format itself was about to go completely and permanently out of fashion. If Strauss was to continue to innovate, it had to be in a different form.

Family Relations

Strauss married the soprano singer Pauline de Ahna in 1894. As a wedding present, Strauss presented his wife with four songs (4 Lieder, op. 27). For a man whose music caused endless sensational headlines in the press, Strauss lived a remarkably quiet family life: "never was there the least hint of scandal in his private life" (Schonberg, 486). Richard and Pauline had a son, Franz (nicknamed Bubi), who was born in 1897.

The Strauss Operas

In the 1890s, Strauss turned to the field of opera. He composed his first opera Guntram in 1894, but it was not a success. It was seven years before he made a second attempt: Feuersnot (Fire Famine), but that fared no better than Guntram. In 1898, Strauss was appointed the chief conductor of the Berlin Royal Opera. Undeterred by the poor showing of his first operas, Strauss was third time lucky with Salome in 1905. The one-act libretto of Salome is based on the play by Oscar Wilde which caused a great scandal. The plot has the imprisoned John the Baptist declare the coming of the Messiah. King Herod asks Salome to dance, which she does on the condition she may have one wish. Salome asks for the head of John the Baptist, dances, and so receives it, and then kisses and caresses it (hence the scandal). Herod (like a good number of critics) is disgusted and orders his soldiers to crush Salome to death with their shields. The score of Salome shows the influence of Wagner and was "a masterpiece of sensuous, overblown late Romanticism" (Wade-Matthews, 425). Besides the storyline, some critics were shocked at the modernity of the orchestration, others thought it a masterpiece – Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) was of the latter opinion.

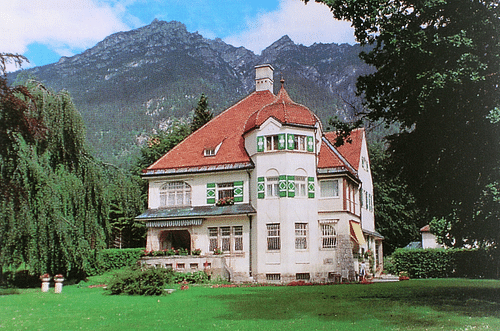

Salome, despite some initial wrangling with censors in various countries, gained Strauss more international fame following its premiere in Dresden in December 1905, New York in 1907 (where it was withdrawn after a single performance due to public outrage), and London in 1910. With his earnings, the composer built himself a huge villa in the mountain resort of Garmisch in Bavaria. Strauss became very wealthy, for "it was known that Strauss drove a hard bargain and liked the sound of crisp money as much as the sound of crisp strings" (Schonberg, 486). He was particularly enthusiastic about extending copyright protection for composers, and in this endeavour he was successful.

The next opera, Elektra, is based on the play of that name by the writer of the Greek tragedy Sophocles (c. 496 to c. 406 BCE). The one-act libretto is by Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929) and tells of Elektra, who plots revenge for the death of her father Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, at the hands of his wife (and Elektra's mother) Klytemnestra. In a family bloodbath, Elektra is helped by her brother Orest who kills Klytemnestra in the royal palace while Elektra kills her mother's lover Aegisth. Elektra gets her comeuppance for her dark deeds when she collapses and dies while dancing in short-lived triumph. The opera premiered in January 1909 at Dresden's Court Opera. Elektra was an international success, securing Strauss' status as one of the world's most important composers and a true master of the soprano voice.

Der Rosenkavalier (The Knight of the Rose) is a comic opera in the mode of similar works by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) with its farcical romance involving a bit of cross-dressing. The three-act libretto is again by Hofmannsthal. The opera premiered in January 1911 to great acclaim and was staged in London and New York two years later. There were plans to make a cinema version of the opera, but Strauss turned down a handsome fee because the producers would not agree to his demand for an uncut version.

Strauss did not give up entirely on symphonic poems in this period of intense opera writing. In 1915, he completed his Ein Alpensinfonie (An Alpine Symphony), an ambitious work with an expanded orchestra (so much so, it is rarely performed today). Inspired by the idea of climbing an alpine peak from dawn to dusk, the unusual percussion section included wind and storm machines.

Further collaborations for operas with Hofmannsthal between 1914 and 1932 included Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten (The Woman Without a Shadow) – Strauss thought this his best opera –, Die ägyptische Helena (The Egyptian Helen), and Arabella. These scores displayed a new luxurious elegance, which resulted in some critics lamenting the change from the more experimental dissonance Strauss had employed in Salome and Elektra. Strauss himself acknowledged that he thought those two earlier operas had tested the limits of what an audience could bear to listen to, and now he stepped back to focus on more depth of meaning rather than sensational effects.

Other collaborators for librettos through the 1930s included Stefan Zweig for Die schweigsame Frau (The Silent Woman) and Joseph Gregor for Friedenstag (Peace Day), Daphne, and Die Liebe der Danaë (Danaë's Love). Strauss' final opera was the one-act Capriccio (libretto by Clemens Krauss and Strauss), which premiered in Munich in 1942. It is, perhaps, a fitting conclusion to the composer's operatic career since the plot revolves around an unresolved debate as to which is more important in an opera, the words or the music.

Associations with Nazism

As the German Nazi Party took power and extended its influence on the arts through the 1930s, Strauss became associated with Nazism. The composer was appointed president of the Nazi Reichsmusikkammer (Reich Chamber of Music) in 1933. In 1935, Strauss was dismissed from the position because his daughter-in-law was of Jewish parentage. He also made a dangerous stand and refused to cut professional ties with his librettist Zweig, who was Jewish. Strauss was consequently required to resign from all of his official positions, but this did not prevent him working further with the regime, notably providing the score for a film on the 1936 Berlin Olympics. During the Second World War (1939-45), Strauss resided in Austria. After the conflict, he moved to Switzerland. The composer was investigated for his past associations with the German Nazi party but was cleared by a denazification tribunal. As the music historian D. Arnold notes, "Strauss found himself accused of co-operating with the [Nazi] regime, though the evidence suggests that he was simply apolitical, and that he did attempt to help his Jewish friends" (1757). Nevertheless, the composer's position is ambiguous, and the fact remains that Strauss' music and reputation have struggled to extract themselves from the shadow of Nazism ever since.

Richard Strauss' Most Famous Works

The most famous works by Richard Strauss include (with first performance dates noted in brackets for the operas):

Over 200 songs

Serenade for wind instruments

Macbeth symphonic poem

Don Juan symphonic poem

Tod und Verklärung – Death and Transfiguration symphonic poem

Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche – Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks symphonic poem

Also sprach Zarathustra – Thus Spoke Zarathustra symphonic poem

Don Quixote symphonic poem

Ein Heldenleben – A Hero's Life symphonic poem

Symphonia domestica symphonic poem

Salome opera (1905)

Elektra opera (1909)

Der Rosenkavalier – The Knight of the Rose opera (1911)

Ariadne auf Naxos – Ariadne on Naxos opera (1912)

Ein Alpensinfonie – An Alpine Symphony symphonic poem

Capriccio opera (1942)

Vier letzte Lieder – Four Last Songs

Death & Legacy

Strauss' post-war work includes Metamorphosen, a work principally for solo strings and meant to represent the demise of Germany under Nazism and the destruction during the war of such great cultural buildings as the opera houses of Dresden, Munich, and Vienna. He also wrote concertos for horns and oboe and several sonatas for wind instruments.

His collection Vier letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs) was composed in 1948 (but not performed until 1950). These songs are for solo singers with orchestral accompaniment and with texts based on the poems of Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff and Hermann Hesse. Strauss had intended there to be a fifth song, but it was never completed. To the end, Strauss, despite his earlier forays into the Modernist musical landscape, adhered to the Romantic movement, which he had outlived, preferring to ignore the developments in music made by such figures as Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) and Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971). This made Strauss' work ripe for criticism from the new generation of Modernist composers, but his position as one of the great composers of the late-19th and early-20th century was by now secure, as evidenced by a festival of his work held in London in 1947. Richard Strauss died at his villa in Garmisch on 8 September 1949.