Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism, a new exhibition at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York, explores the dynamic historical intersection of politics, religion, and art as reflected through Tibetan Buddhism. The exhibition underscores how Tibetan Buddhism presented a model of universal sacral kingship, whereby consecrated rulers were empowered to expand their realm, aided by the employment of ritual magic between the 8th to the 19th centuries CE. While the force of religion to claim political power is a global phenomenon, Faith and Empire reveals how Tibetan Buddhism once offered such divine means to power and legitimacy to rulers in East Asia. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to the Rubin Museum's Karl Debreczeny about Tibet's dual role as a source of artistic production and political power within East Asia.

JBW: Thanks for speaking with me Curator Karl Debreczeny about Faith and Empire, which recently opened at the Rubin Museum. While the exhibition ties nicely into the Rubin Museum's theme for 2019 - “power” - what provided the impetus for this show?

KD: I have long been interested in the relationship between the Tibetan and Chinese artistic traditions, especially the interest of the various imperial courts (the Tanguts, the Mongols, the Chinese, and the Manchus) in Tibetan Buddhism and their patronage of Tibetan Buddhist Art at the highest levels of artistic production. What was their motivation? What were the sources of their inspiration? Why did they pour so many resources in the recreation of icons in the luxury medium of silk and monumental sculptures in gilt bronze and lacquer? Rulers and imperial courts were less interested in meditation or enlightenment and more concerned with what religion could do for the state: protecting the nation; extending the life, wealth, and authority of its rulers; curing epidemics; controlling the weather; and pacifying or killing its enemies — in a word, power.

Also, as the relationship between politics and religion is a universal phenomenon found across time and cultures, it requires no specialized knowledge to understand, and thus this thematic approach allows the visitors an accessible window into a little-known aspect of this tradition.

JBW: Religion and politics have always enjoyed a symbiotic relationship; indeed, sacred art has served as both an active agent and primary medium of government propaganda throughout human history. Some of the earliest surviving evidence of visual expressions of Tibetan political power in religious art dates to the apogee of the Tibetan Empire, which emerged in 618 CE and came to rule over large parts of what is now China and Central Asia over the course of the 8th century CE.

The Tibetan Empire was so powerful that Tibetans even occupied the famed city of Dunhuang, which was an important center of Buddhist cave temples and religious translation near the eastern terminus of the Silk Road. Could you tell us more about the importance of the Tibetan occupation of Dunhuang, Curator Debreczeny? How did the presence of Tibetans at Dunhuang influence art and artistic production in the region?

KD: From the 7th to the 9th century CE, Tibetans first dramatically stepped onto the world stage in the form of the Tibetan Empire (c. 608–866 CE), which became one of the great military powers of Asia and the greatest military rival of the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). The earliest surviving political expressions of Tibetan power in art date to this period, when the Tibetan Empire ruled over large subject populations in the Hexi area of Gansu, including Dunhuang, an important center of international Buddhist activity at the eastern end of the Silk Road.

9th-century CE Tibetan documents describe Tibetan state patronage at Dunhuang on the occasion of the signing of the Sino-Tibetan Treaty of 822 CE, when this area was ceded by the Tang to the Tibetan Empire. The theme of sacrosanct rulership is stated directly, with the aspiration that the Tibetan emperor become a sacral ruler (chakravartin), exercising authority over the four continents and other kingdoms as well.

Three silver vessels in the exhibition are a testament to the cosmopolitan nature of the Tibetan Empire, embracing many surrounding traditions, including a writing system based on Sanskrit, Buddhism introduced by monks from Khotan in Central Asia and scholars from India, Greek medicine by way of Persia, record keeping drawn from Tang China, and Sasanian silver-working techniques via the Sogdians. Part of this internationalism resulted from Tibetan rule over portions of the Silk Road, an important economic artery that linked Asia with the West.

The earliest surviving Sino-Tibetan artistic exchange also dates to the 8th and 9th centuries CE, when the Tibetan Empire ruled over large Chinese subject populations in the Hexi area of Gansu, including Dunhuang. Tibetans patronized local workshops while introducing new visual forms into the local established traditions, as represented in the exhibition by a painting from the Musee Guimet. When the Tibetan Empire took control of this important center of Buddhist activity in 781 CE, Tibetan Buddhism and art were still in their formative stages. The first Tibetan monastery, Samyé, had been founded only two years earlier in 779 CE, coinciding with the adoption of Buddhism as Tibet's state religion. Thus, the scriptural translation and artistic activities at Dunhuang also had a significant impact on what was to become Tibetan Buddhism.

Moreover, after this area fell to the Tibetans, generations of its largely Chinese inhabitants learned to speak and write Tibetan and were subject to Tibetan laws and overseen by Tibetan officials. The cultural, linguistic, and religious impact of Tibetan culture in Dunhuang far outlived the Tibetan occupation, which ended in 848 CE but left a long-standing legacy in administrative, diplomatic, scriptural, and artistic production, and the Tibetan language was still in widespread use in the region into the 10th century CE.

JBW: After the Tibetan Empire collapsed in 842 CE, there was a protracted period of political fragmentation and chaos in Tibet; the lack of a centralized political or religious authority gave rise to local tantric masters establishing their own authority between the 9th and 12th centuries CE. Tantric practices popular in this period were characterized by more explicit incorporation of sexual and violent imagery. How did these tantric practices affect artistic production and the projection of power through art in Tibet?

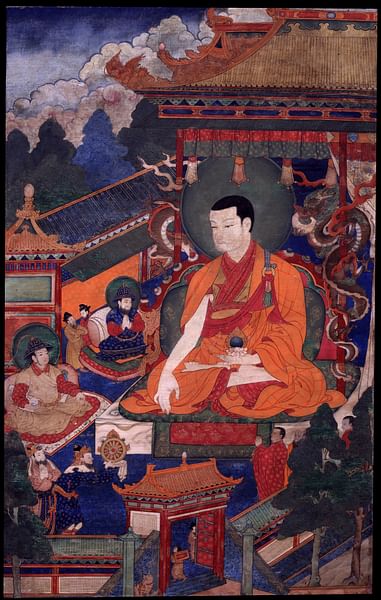

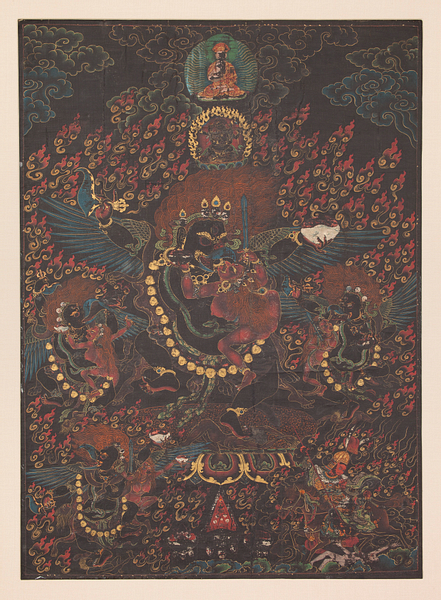

KD: Portraits of tantric masters depicted with qualities of the Buddha were a visual means to project their presence and authority, a conflation of religious and political power. For instance, Lama Zhang (1123-1193 CE) is a fascinating study in the political and martial employment of Tantric Buddhism during the late 12th century. He directly involved himself in political and military affairs, ruled territory, and enforced secular law. He even sent his own students into battle to work siege engines as part of their religious practice. Equipped not only with conventional weapons, Lama Zhang also employed a ritualized warfare of magic spells, purportedly aided by powerful protector deities such as Shri Devi and Mahakala. Lama Zhang's tutelage also helped lay the foundations for the Tangut's involvement with the cult of the wrathful protector deity Mahakala as a means for worldly power.

JBW: The Tangut court of Western Xia - also known as the Empire of Xixia (1038-1227 CE) - was a small but powerful multiethnic kingdom along the Silk Road that established many of the court ritual practices of Tibetan Buddhism and art by the late 12th century CE. Tibetan and Chinese religious and artistic traditions were integrated through Tangut patronage, creating a new visual model of sacral rule that included both political and artistic forms.

How did Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan art serve the state in the legitimization of political authority of a Tangut ruler over a multiethnic kingdom? Additionally, how were Tangut rulers and elites able to engender the lavish system of imperial patronage?

KD: The Tanguts employed a self-conscious multicultural strategy, editing texts in three languages at once: Tangut, Chinese, and Tibetan. Their art also mixed Chinese and Tibetan iconographies as well as stylistic traditions to meet the Tangut patron's particular needs. One hallmark of the Tangut court was the use of the Chinese luxury medium of silk for making Tibetan Buddhist images. Slit-silk (kesi 缂丝) tapestry, for instance, was a technique developed in Central Asia and adopted by the Tangut court for the making of Tibetan Buddhist icons. Tiny seed pearls woven into a silk tapestry in the exhibition reveal the lavishness of these court commissions. The Mongol Empire adopted this tradition of creating Tibetan icons in silk tapestry. The Tanguts were the source of many such imperial court practices integrating Tibetan Buddhist imagery with Chinese media and artistic techniques, and these practices were emulated for centuries.

Tibetan Buddhists, known for the efficacy of their ritual magic, also served the Tangut court as imperial preceptors. One cleric who is tied to the Tangut imperial line, Tsami Lotsawa, is linked to at least 16 texts on the wrathful deity Mahakala, known for its military efficacy, including one called The Instructions of Shri Mahakala: The Usurpation of Government, a short “how-to” work on overthrowing a state and taking power. Later, when Genghis (Chinggis) Khan first laid siege to the Tangut capital in 1210 CE, the Tangut's last Tibetan Buddhist imperial preceptor Tishri Repa (1164-1236 CE) summoned Mahakala. When he threw a dough effigy (torma), he saw a vision of the deity on the battlefield, at which point the dams the Mongols were using to flood the city burst, drowning Mongol troops and forcing Genghis to withdraw. This account of their unusual military setback through effective religious ritual no doubt caught Mongol attention.

JBW: Why was Tibetan Buddhist art especially attractive to the dynasties of imperial China; namely, the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271-1368 CE), the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE), and the Manchu Qing dynasty (1644-1912 CE)? In what ways should we think of medieval and early modern Tibetans as “imperial preceptors” of Chinese dynasties?

KD: For several centuries Tibetan Buddhism offered a divine means to power and legitimacy to rule in Inner Asia and China. Tibetan Buddhism provided both a symbolic path to legitimation in the form of sacral kingship and a more literal means in tantric ritual technologies to physical power in the form of magic. The use of reincarnation as a means of succession was a unique Tibetan model of political legitimacy employed by courts in Tibet and brought to empires to the east. Images were one of the primary means of political propagation, integral to magical tantric rites, and embodiments of power.

Imperial preceptor and state preceptor were some of the important political roles Tibetan Buddhists played in the courts of Inner Asia and China from the late 12th to the early 20th century. The Tanguts first established the practice of making Tibetan Buddhists imperial preceptors, a practice emulated by the Mongols once Xixia was absorbed into the Mongol Empire.

In 1260 CE, Kublai (Qubilai) declared himself Great Khan, leading to fragmentation of the Mongol Empire. His Tibetan preceptor Phakpa initiated Kublai into Tibetan Buddhist sacral rites. In 1270 CE, Kublai Khan appointed the Tibetan cleric Phakpa imperial preceptor, the highest religious authority in the land, just prior to the founding of the Yuan dynasty. These two key political moments, as understood by later Tibetans, are depicted in two portraits of Phakpa in the exhibition. Until the fall of the dynasty, it was Yuan practice to appoint Tibetans as imperial preceptors. While the title 'imperial preceptor' was never revived after the fall of the Yuan, the relationship between the Mongol emperor Kublai and his Tibetan chaplain Phakpa became a model that subsequent imperial courts and Tibetans would invoke it for centuries to come.

Tibetan Buddhist images were also central to state ritual and prominent symbols of state power. For instance, during the 13th century, the wrathful figure of Mahakala became a Mongol state protector and focus of the imperial cult. Mahakala was credited with intervening in several key battles, and temples dedicated to this deity were built throughout the empire. Most famously, during the campaign to conquer southern China, Kublai asked Phakpa for Mahakala to intervene against the Chinese Southern Song. In 1275 CE, Kublai's Nepalese court artist Anige (1244-1306 CE) constructed a temple with its statue facing south, Phakpa performed the rituals, and soon after the Song capital fell. This sculpture became a potent symbol of both Kublai's rule and the Yuan imperial lineage. This association was so strong that four centuries later the Manchus, lacking the proper bloodlines, traced their own spiritual ancestry to Kublai Khan as the rightful inheritors of his Yuan legacy. In 1635 CE, shortly before the founding of their Qing dynasty in 1644 CE, they installed what they declared to be the same statue of Mahakala in their imperial shrine.

Even after the Mongol Yuan dynasty collapsed and the Chinese reclaimed their land, establishing the Ming dynasty, the Chinese court continued to follow Mongol precedents for an imperial Buddhist vocabulary symbolic of divine rule. By this time Kublai Khan's model of rulership was recognized across much of the Eurasian continent. The early Ming rulers employed this accepted language of power to declare their authority. The Yongle emperor (r. 1402-1424 CE) was the first Ming emperor to establish significant ties with Tibetan patriarchs. Yongle had seized the throne, thus a cloud hung over his legitimacy. As part of his strategy to bolster his right to rule, Yongle invited the Tibetan hierarch the Fifth Karmapa (1384-1415 CE) to the early Ming capital of Nanjing.

In dealing with the Karmapa, Yongle consciously drew parallels in his own actions to Kublai Khan's relationship with his Tibetan imperial preceptor Phakpa. According to Tibetan sources, Yongle expressed an interest in re-creating their relationship. The Karmapas were of particular interest to Yongle, as they were prominent preceptors at the late Yuan court and were viewed as anointers of sacral kingship par excellence. Indeed, after the Karmapa's visit, Yongle styled himself a universal sacral ruler (chakravartin). A great deal of Tibetan Buddhist art was produced in the imperial workshops to underline his authority and right to rule.

The Manchus, like the Mongols, were a people from north of the Great Wall who conquered China and assumed Tibetan Buddhism as a means of political legitimacy in ruling a vast multiethnic empire. During their Qing dynasty, Tibetan Buddhism was once again an official religion of the empire. Under the Manchus the visual language of Buddhist imperial rule was further refined and the concepts of sacral legitimacy given a finer point, with a special focus on the cult of the Bodhisattva of Wisdom Manjushri. The Manchu emperors, lacking the proper bloodlines to the Mongol ruling house, traced their own spiritual ancestry to Kublai Khan through the Tibetan succession mechanism of reincarnation. By promoting themselves as emanations of Manjushri they declared themselves Kublai Khan reborn and the rightful inheritors of his Yuan legacy. The production of religious art propagated the Manchu inheritance of Kublai's realm.

It was the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736-1795 CE) more than any other Manchu ruler who realized the potential of patronizing Tibetan Buddhism, as is evidenced by the incredible volume of Tibetan Buddhist images produced by the imperial workshops. The Qianlong emperor's Tibetan Buddhist state preceptor, Changkya Rolpai Dorje (1717-1786 CE) (Fig. 12 Portrait Sculpture of Changkya Rolpai Dorje), had a guiding hand in the formation of Sino-Tibetan imperial Buddhist art of the Qing dynasty, which came to symbolize Manchu rulership. Rolpai Dorje's incarnation lineage was carefully crafted to reflect that the patron-priest relationship between Kublai Khan and Phakpa was reborn, quite literally, in Qianlong and himself. In 1745 CE, Rolpai Dorje initiated Qianlong into the rites of a divinely anointed sovereign, much as Phakpa did for Kublai. Later, when Rolpai Dorje translated Phakpa's biography into Mongolian in 1753 CE, he drew a direct parallel between the two acts, ruminating that he and the emperor were connected through many lifetimes. He also stated directly that Kublai was a predecessor of Qianlong in the Manjushri incarnation lineage. During Lord McCartney's 1793 CE embassy, a Tartar (Mongol) official told the British diplomat that the Qianlong emperor was an incarnation of Kublai Khan, suggesting that this association was well known.

This political engagement with Buddhism does not necessarily signify that leaders ruled these empires as idealized Buddhist kingdoms. Their employment of religious rhetoric was part of their claim to legitimacy, and their deployment of religious ritual was one of the means by which they sought to take and maintain power.

JBW: Of the 60 objects on display at Faith and Empire, which among them are especially notable and why? What challenges did you face in organizing the show and assembling the objects on display?

KD: The painting of the Deities of the Padmakula Mandala is a very rare example of the highest quality of art produced during the period of Tibetan rule of Dunhuang in a Western collection. After all, we are unable to bring the famous wall paintings from Dunhuang into our gallery (though we do discuss them in the publication). It also reflects a new aesthetic that the Tibetans introduced to the territories they ruled.

An early 13th-century CE slit-silk tapestry of the wrathful deity Achala is the best example of Tangut Xixia production of Tibetan icons in silk in an American public collection. The tiny seed pearls woven into the silk reveal the lavishness of these commissions.

A remarkably intricate silk embroidery from the Yongle period of Hevajra has a long inscription that reveals how Tibetan icons produced in the Chinese court could serve political purposes. In this case, it served as both a diplomatic gift to a prominent Tibetan and documentation of imperial legitimacy. This work has never been shown before.

An early 15th-century CE 1.4 m 172 kg (4½-foot-tall 380 lbs.) gilt bronze sculpture from Musée Cernuschi, Paris, originates from a network of Ming court-supported temples along the Sino-Tibetan frontier which were sites of political propagation, a projection of imperial power into contested borderlands, conveyed through a mixture of Chinese imperial architecture and an international Buddhist visual vocabulary. This is probably the most dramatic object in the gallery, and it was one of the most challenging to bring here and install: we had to take the doors off the building to get its crate into the museum.

A life-size hollow dry lacquer sculpture of the Buddha Amitayus is representative of the grand scale of Tibetan Buddhist art produced at the Qing court under the Qianlong emperor, and it was presumably made for one of the many temples they built at the imperial summer capital of Chengde. The Yuan imperial workshops used dry lacquer to recreate large-scale images, so by using these materials, the Qing court connected themselves to the Mongol imperial legacy.

An 8-foot-wide 19th-century CE Mongolian painting of the Kingdom of Shambhala and the Final Battle depicts a millenarian myth of a time when barbarians have taken over the earth and the last king of Shambhala rides forth with his armies to destroy the non-believers, ushering in a new golden age. When various rebellions from Muslims, Christians, and others threatened the Qing, they used this end-of-the-world prophecy to politically mobilize the Mongols to come to the aid of the failing Qing state.

Part of the difficulties of negotiating loans from such a wide range of public and private institutions in both the United States and Europe is, of course, the cost of such an endeavor for a relatively small public institution like the Rubin Museum, so we had to make choices. Also, not all of the objects we had hoped to include were approved. However, all objects essential to the narrative are included in the publication, which is intended as a stand-alone work, with a series of ten essays by a wide range of scholars working in disciplines such as history, art history, and religious studies (including contributions translated from Tibetan and Chinese).

JBW: If there is one thing that the public should know about medieval and early modern Tibetan art and its widespread influence across East Asia, what is it? Moreover, what do you hope visitors come away with following a visit to Faith and Empire?

KD: Tibetan Buddhism played a significant and sustained political role, and it is through this lens that Faith and Empire seeks to place Himalayan art in a larger global context and highlight a dynamic aspect of the tradition related to power, one that may run counter to popular perceptions yet is critical to understanding its importance on the world stage.

Also, I hope that through exploring these universal issues visitors might be inspired to reflect on the relationship between politics and religion in our own time.

JBW: Thank you for your time and consideration, Curator Karl Debreczeny. Congratulations on your exhibition!

KD: Thanks, James! I welcome Ancient History Encyclopedia readers to the Rubin Museum, and I hope they enjoy the show.

Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism runs until July 15, 2019 at the Rubin Museum in New York, NY.

Dr. Karl Debreczeny is Senior Curator, Collections and Research at the Rubin Museum of Art. He received masters' degrees from Indiana University in both art history and Tibetan studies (1997) and earned a doctorate in art history from the University of Chicago (2007). His research focuses on exchanges between Tibetan and Chinese artistic traditions, and he is currently leading a comprehensive assessment of the Rubin Museum collection. He has curated several exhibitions for the Rubin Museum of Art including “The All Knowing Buddha: A Secret Guide” (2014); “Wutaishan: Pilgrimage to Five Peak Mountain” (2007); “Patron and Painter: Situ Panchen and the Revival of the Encampment Style” (2009); “Remember That You Will Die: Death Across Cultures” (2010); and “Lama Patron Artist: The Great Situ Panchen” (2010) at the Smithsonian Freer-Sackler Gallery of Art, Washington DC. His latest publication is Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism, which is available through the University of Washington Press.