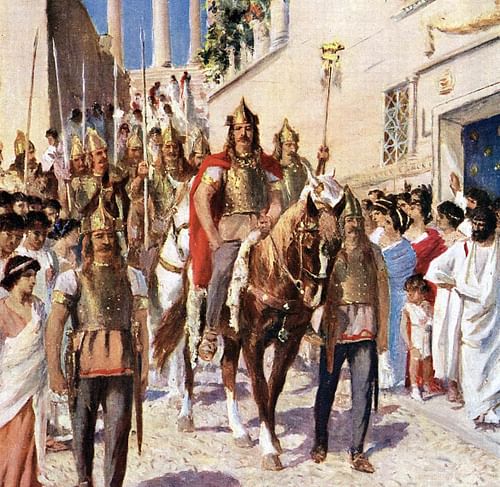

In August of 410 CE Alaric the Gothic king accomplished something that had not been done in over eight centuries: he and his army entered the gates of imperial Rome and sacked the city. Although the city and, for a time, the Roman Empire would survive, the plundering left an indelible mark that could not be erased. Alaric and his army marched through the Salarian Gates and pillaged a city that had earlier suffered famine and starvation. Although they left churches such as Saint Peter and Saint Paul untouched, the army destroyed pagan temples, burned the old Senate House, and even kidnapped Emperor Honorius' sister Galla Placidia.

The Goths

Since the early days of the Empire, Rome had continually struggled with the protection of its frontier borders. So, when the Gothic tribes - the Tervingi and Greuthungi - sought refuge from the marauding Huns, the Romans contemplated the options and eventually allowed them to settle on the Balkan frontier, of course, at a cost. Alliances were made and alliances were broken. Many in Rome remained unhappy with the decision and viewed the Goths as nothing more than barbarians although most of them were, in fact, Christian. Unreasonable demands were made of the new settlers, and they suffered at the hands of unscrupulous commanders. Facing starvation due to inadequate provisions and a lengthy famine, the Goths rose up against the Romans and began a long series of raids and pillaging of the countryside.

The differences between the two culminated in the Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE. Emperor Valens (r. 364-378 CE) who had only sought only personal glory was soundly defeated. It was a defeat that not only cost the lives of many veteran soldiers but also revealed the military weaknesses of the west. Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) replaced Valens as emperor and another alliance in 382 CE was signed. This new alliance offered land for the Gothic setters in exchange for their providing soldiers for the Roman army. With the defeat of Emperor Magnus Maximus (r. 383-388 CE) in Gaul, Theodosius reunited (for the last time) both the east and west and immediately banned all forms of pagan worship. It appeared that Rome and the Gothic tribes might be, for a time, finally at peace.

Shadow Emperors in the West

With the Theodosius' death in 395 CE, his two young sons Arcadius (r. 395-408 CE) and Honorius (r. 395-423 CE) were named as his successors - Arcadius in the east and Honorius in the west. Since Honorius was only ten at the time, Flavius Stilicho, the magister militum or commander-in-chief, was named as regent. The half-Vandal half-Roman Stilicho's attempt to assume regency over the east failed. It was something that would plague him for years to come.

Unfortunately for the west, the emperors from Valens to Romulus Augustus (r. 475-476 CE) proved to be highly incompetent, isolating themselves from forming policy and becoming increasingly dominated by the military. They were sometimes referred to as the “shadow emperors.” Honorius did not even live in Rome but had a palace at Ravenna. The east and west began to gradually drift apart as the west became more and more susceptible to attack. The weakness of the west became evident when in 406 CE Vandals, Alans, and Suevi crossed the frozen Rhine into Gaul, eventually marching further south into Spain. The Roman troops who normally defended Gaul had been withdrawn to face a usurper from Britain, the soon-to-be Constantine III. With a government in crisis, the time had finally come for the Gothic tribes to rise up against the Romans.

Stilicho

The Goths had never completely trusted the Romans holding to their promises of 382 CE and hoped to rewrite the old alliance made with Theodosius. The Goths especially disliked the clause making them provide soldiers to the Roman army. It was a condition they believed would severely weaken their own defences. The disparity between Rome and the Goths grew, forcing them to return to the practice of ransacking the Balkan countryside. Although long desired by Rome, this was an area that was technically part of the empire that belonged to the east. Still hoping to rewrite the alliance, the Goths changed their strategy and planned to forge a new deal with Arcadius; a plan that would ultimately fail.

Alaric, who had fought at the Battle of the River Frigidus and even allied himself with Stilicho, turned his attentions to the west and Emperor Honorius, eventually leading to the invasion of Italy in 402 CE. His demands for peace were simple: he wanted to be named a magister militum - a title that would give him prestige and help the Gothic status in the empire, - food subsidies, and a percentage of the crops raised in the region. Stilicho, speaking on the behalf of Honorius, said no to all of the demands. With no hope for a new alliance, the two sides clashed twice with no clear winner, both sides suffering heavy losses. Alaric was forced to retreat having been cut off from his supplies.

Despite their differences, Stilicho hoped to appease Alaric with a new alliance: rights in exchange for securing the frontier border against future invasions. In the new proposal Alaric and Stilicho would work together to secure the Balkans for the west. Stilicho had had his eye on the Balkans since being named Honorius' regent. He believed the Balkans would provide additional (and much needed) troops for the Roman forces in the west. Alaric moved eastward and waited for his new ally to arrive. Unfortunately, Stilicho would never arrive. He was detained; the Gothic king Radagaisus crossed the Danube and invaded Italy only to be defeated and executed, the Vandals and their allies crossed the Rhine into Gaul, and Constantine III, the usurper from Britain, was declared emperor by his army and soon had Gaul and Spain under his control. Stilicho was overwhelmed and desperately needed money to wage war against the invaders. Alaric, still waiting in the east, also demanded money. His new ally, Stilicho, appealed to the Roman Senate to approve a possible peace with Alaric. Unfortunately, the hawkish Roman senator Olympius disagreed and wanted only war.

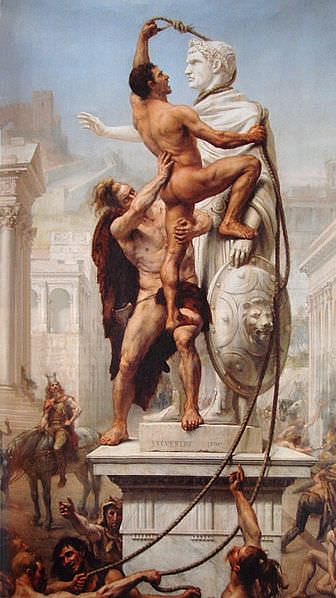

Sack of Rome

All the problems appeared to be the fault of Stilicho. Accusations were also aimed at Stilicho, questioning his intent in the east. Honorius, now listening more to Olympus than Stilicho, agreed, and his former regent was arrested and executed. The only real chance for peace with Alaric was gradually disappearing. Alaric took the death of Stilicho to be a sign of things to come and turned his attention to Italy; towns such as Concordia, Cremona, and Ariminum soon fell to his army. Instead of obviously seizing the Ravenna home of Honorius, he turned his attention to Rome, believing it would be a more suitable hostage. He surrounded all 13 gates. Supplies in the city soon ran low: food was rationed, corpses littered the streets, a stench filled the air, but Honorius refused to help. The Tiber was cut off from access to the port of Ostia and supplies of grain from North Africa. Rome became a “ghost town.”

With the arrival of Alaric's brother-in-law Athaulf with additional forces of Goths and Huns, Rome, who had vowed to fight to the bitter end, realized a truce must be reached. Alaric agreed to lift the siege in exchange for 12 tons of gold, 13 tons of silver, 4,000 silk tunics, 3,000 fleeces, and 3,000 pounds of pepper. The Roman Senate was desperate: statues had to be melted and the treasury was completely emptied, but the siege was over and supplies began arriving.

Although Alaric and his brother had riches, they still hoped to negotiate a new alliance with Honorius. The Senate agreed and the reluctant emperor appeared willing to talk. Representatives from the Senate were sent to Ravenna. In reality, however, the talks were only a delaying tactic until Roman troops arrived from the east. Alaric would soon learn of the treachery behind the emperor and his commander Olympius. Although Honorius agreed in principle to much of an alliance, he agreed with Olympius that any land grant would spell disaster for Rome. Land grants would mean no revenue for the empire, no revenue meant no army, and no army meant no empire. While there still appeared to be some hope, Alaric and his army withdrew from the city.

Honorius used the Gothic army's departure to dispatch 6,000 soldiers to Rome. Alaric spotted the Romans, pursued them, and wiped out all 6,000 troops. About the same time, Athaulf and his Gothic force were attacked by the Romans under the leadership of Olympius. Losing over 1,000 men, Athaulf reorganized and attacked the Roman forces, causing Olympius to retreat to Ravenna. Honorius was desperate and quickly dismissed Olympius who fled to Dalmatia.

Honorius turned to his commander-in-chief Jovius who invited Alaric and Athaulf to Ariminum to negotiate a new alliance. Jovius had been instrumental in forging the alliance between Stilicho and Alaric. The Romans had no alternative. If they fought Goths they faced the possibility of diminishing the Roman forces and thereby opening the door for an invasion from Constantine. Although he had little trust in the emperor's promises, Alaric still hoped for a settlement. Alaric's terms were simple: an annual payment of gold, an annual supply of grain, and land for the Goths in the provinces of Venetia, Noricum, and Dalmatia. In addition he wanted a generalship in the Roman army. The reply was yes to the grain supply but no to the land and generalship. Alaric left the meeting, threatening to sack and burn Rome. After a few days to regain composure, Alaric wanted an end to war and said he would be willing to settle for land in Noricum. Honorius completely refused, leaving the enraged Goth with little alternative but to march on Rome.

A surprise attack by the Roman commander Sarus left little hope for any truce. With a little help from inside the city, the Salarian gate was opened, and Alaric and his army of 40,000 marched into the city. While leaving the Christian churches untouched and those seeking refuge inside alone, the Goths raided the pagan temples and the homes of the rich, demanding gold and silver. Many houses of the rich and some, not all, public buildings were burned. Historian Peter Heather in his book The Fall of the Roman Empire claims that Alaric did not want to the sack the city. He had been outside the city for months and could have sacked it at any time. His only goal was, as it always had been, to negotiate a new alliance, rewriting the one forged in 382 CE. Others, however, saw the sacking of the city in a different light. Heather wrote that many non-Christians believed that fall of the city was due to the abandonment of the imperial religion while Saint Augustine, speaking on behalf of the Church, saw it as an indication of the empire's centuries-old desire to dominate.

Aftermath

The next two decades would bring drastic changes to the west. The Goths would leave Rome and eventually find a permanent home in Gaul. Shortly after leaving the city, Alaric would die of illness - his gravesite is unknown - leaving his brother to lead the Goths. Leadership of the west would also change: Honorius would die in 423 CE while the usurper Constantine III would be defeated by Constantius. Athaulf would not lead the Goths very long. After marrying Galla Placidia, he would die (possibly murdered) in 415 CE. Galla would return to her brother's forgiving arms. She would be forced to marry Constantius. Their son would be Valentinian III (425-455 CE), the future emperor in the west. She would serve as her son's regent. In 476 CE the barbarian Odoacer and his army would ride into Italy and depose the young emperor Romulus Augustus. Oddly, the conqueror would not assume the title of emperor. Although arbitrary, the year 476 CE is recognized by most historians to indicate the fall of the west, but the sack of the city in 410 CE had brought the city to its knees, and it never recovered. The Byzantine Empire in the east would, however, survive until falling to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE.