The artworks of ancient Egypt have fascinated people for thousands of years. The early Greek and later Roman artists were influenced by Egyptian techniques and their art would inspire those of other cultures up to the present day. Many artists are known from later periods but those of Egypt are completely anonymous and for a very interesting reason: their art was functional and created for a practical purpose whereas later art was intended for aesthetic pleasure. Functional art is work-made-for-hire, belonging to the individual who commissioned it, while art created for pleasure - even if commissioned - allows for greater expression of the artist's vision and so recognition of an individual artist.

A Greek artist like Phidias (c. 490-430 BCE) certainly understood the practical purposes in creating a statue of Athena or Zeus but his primary aim would have been to make a visually pleasing piece, to make 'art' as people understand that word today, not to create a practical and functional work. All Egyptian art served a practical purpose: a statue held the spirit of the god or the deceased; a tomb painting showed scenes from one's life on earth so one's spirit could remember it or scenes from the paradise one hoped to attain so one would know how to get there; charms and amulets protected one from harm; figurines warded off evil spirits and angry ghosts; hand mirrors, whip-handles, cosmetic cabinets all served practical purposes and ceramics were used for drinking, eating, and storage. Egyptologist Gay Robins notes:

As far as we know, the ancient Egyptians had no word that corresponded exactly to our abstract use of the word 'art'. They had words for individual types of monuments that we today regard as examples of Egyptian art - 'statue', 'stela', 'tomb' -but there is no reason to believe that these words necessarily included an aesthetic dimension in their meaning. (12)

Although Egyptian art is highly regarded today and continues to be a great draw for museums featuring exhibits, the ancient Egyptians themselves would never have thought of their work in this same way and certainly would find it strange to have these different types of works displayed out of context in a museum's hall. Statuary was created and placed for a specific reason and the same is true for any other kind of art. The concept of "art for art's sake" was unknown and, further, would have probably been incomprehensible to an ancient Egyptian who understood art as functional above all else.

Egyptian Symmetry

This is not to say the Egyptians had no sense of aesthetic beauty. Even Egyptian hieroglyphics were written with aesthetics in mind. A hieroglyphic sentence could be written left to right or right to left, up to down or down to up, depending entirely on how one's choice affected the beauty of the finished work. Simply put, any work needed to be beautiful but the motivation to create was focused on a practical goal: function. Even so, Egyptian art is consistently admired for its beauty and this is because of the value ancient Egyptians placed on symmetry.

The perfect balance in Egyptian art reflects the cultural value of ma'at (harmony) which was central to the civilization. Ma'at was not only universal and social order but the very fabric of creation which came into being when the gods made the ordered universe out of undifferentiated chaos. The concept of unity, of oneness, was this 'chaos' but the gods introduced duality - night and day, female and male, dark and light - and this duality was regulated by ma'at.

It is for this reason that Egyptian temples, palaces, homes and gardens, statuary and paintings, signet rings and amulets were all created with balance in mind and all reflect the value of symmetry. The Egyptians believed their land had been made in the image of the world of the gods, and when someone died, they went to a paradise they would find quite familiar. When an Egyptian obelisk was made it was always created and raised with an identical twin and these two obelisks were thought to have divine reflections, made at the same time, in the land of the gods. Temple courtyards were purposefully laid out to reflect creation, ma'at, heka (magic), and the afterlife with the same perfect symmetry the gods had initiated at creation. Art reflected the perfection of the gods while, at the same time, serving a practical purpose on a daily basis.

Historical Progression

The art of Egypt is the story of the elite, the ruling class. Throughout most of Egypt's historical periods those of more modest means could not afford the luxury of artworks to tell their story and it is largely through Egyptian art that the history of the civilization has come to be known. The tombs, tomb paintings, inscriptions, temples, even most of the literature, is concerned with the lives of the upper class and only by way of telling these stories are those of the lower classes revealed. This paradigm was already set prior to the written history of the culture. Art begins in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) through rock drawings and ceramics but is fully realized by the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) in the famous Narmer Palette.

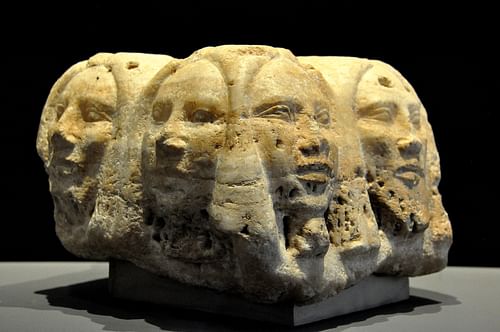

The Narmer Palette (c. 3150 BCE) is a two-sided ceremonial plate of siltstone intricately carved with scenes of the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by King Narmer. The importance of symmetry is evident in the composition which features the heads of four bulls (a symbol of power) at the top of each side and balanced representation of the figures which tell the story. The work is considered a masterpiece of Early Dynastic Period art and shows how advanced Egyptian artists were at the time.

The later work of the architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) on the pyramid of King Djoser (c. 2670 BCE) reflects how far artworks had advanced since the Narmer Palette. Djoser's pyramid complex is intricately designed with lotus flowers, papyrus plants, and djed symbols in high and low relief and the pyramid itself, of course, is evidence of the Egyptian skill in working in stone on monumental artworks.

During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) art became standardized by the elite and figures were produced uniformly to reflect the tastes of the capital at Memphis. Statuary of the late Early Dynastic and early Old Kingdom periods is remarkably similar although other art forms (painting and writing) show more sophistication in the Old Kingdom. The greatest artworks of the Old Kingdom are the Pyramids and Great Sphinx of Giza which still stand today but more modest monuments were created with the same precision and beauty. Old Kingdom art and architecture, in fact, was highly valued by Egyptians in later eras. Some rulers and nobles (such as Khaemweset, fourth son of Ramesses II) purposefully commissioned works in Old Kingdom style, even the eternal home of their tombs.

In the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181 -2040 BCE), following the collapse of the Old Kingdom, artists were able to express individual and regional visions more freely. The lack of a strong central government commissioning works meant that district governors could requisition pieces reflecting their home province. These different districts also found they had more disposable income since they were not sending as much to Memphis. More economic power locally inspired more artists to produce works in their own style. Mass production began during the First Intermediate Period also and this led to a uniformity in a given region's artwork which made it at once distinctive but of lesser quality than Old Kingdom work. This change can best be seen in the production of shabti dolls for grave goods which were formerly made by hand.

Art would flourish during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) which is generally considered the high point of Egyptian culture. Colossal statuary began during this period as well as the great temple of Karnak at Thebes. The idealism of Old Kingdom depictions in statuary and paintings was replaced by realistic representations and the lower classes are also found represented more often in art than previously. The Middle Kingdom gave way to the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE) during which the Hyksos held large areas of the Delta region while the Nubians encroached from the south. Art from this period produced at Thebes retains the characteristics of the Middle Kingdom while that of the Nubians and Hyksos - both of whom admired and copied Egyptian art - differs in size, quality, and technique.

The New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE), which followed, is the best-known period from Egypt's history and produced some of the finest and most famous works of art. The bust of Nefertiti and the golden death mask of Tutankhamun both come from this era. New Kingdom art is defined by high quality in vision and technique due largely to Egypt's interaction with neighboring cultures. This was the era of Egypt's empire and the metal-working techniques of the Hittites - who were now considered allies if not equals - greatly influenced the production of funerary artifacts, weaponry, and other artwork.

Following the New Kingdom, the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE) and Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE) attempted with more or less success to continue the high standard of New Kingdom art while also evoking Old Kingdom styles in an effort to recapture the declining stature of Egypt. Persian influence in the Late Period is replaced by Greek tastes during the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE) which also tries to suggest the Old Kingdom standards with New Kingdom technique and this paradigm persists into Roman Egypt (30 BCE - 646 CE) and the end of Egyptian culture.

Types of Art, Detail, & Symbol

Throughout all these eras, the types of art were as numerous as human need, the resources to make them, and the ability to pay for them. The wealthy of Egypt had ornate hand mirrors, cosmetic cases and jars, jewelry, decorated scabbards for knives and swords, intricate bows, sandals, furniture, chariots, gardens, and tombs. Every aspect of any of these creations had symbolic meaning. In the same way the bull motif on the Narmer Palette symbolized the power of the king, so every image, design, ornamentation, or detail meant something relating to its owner.

Among the most obvious examples of this is the golden throne of Tutankhamun (c. 1336-c.1327 BCE) which depicts the young king with his wife Ankhsenamun. The couple is represented in a quiet domestic moment as the queen is rubbing ointment onto her husband's arm as he sits in a chair. Their close relationship is established by the color of their skin, which is the same. Men are usually depicted with reddish skin because they spent more time outdoors while a lighter color was used for women's skin as they were more apt to stay out of the sun. This difference in the shade of skin tones did not represent equality or inequality but was simply an attempt at realism.

In the case of Tutankhamun's throne, however, the technique is used to express an important aspect of the couple's relationship. Other inscriptions and artwork make clear that they spent most of their time together and the artist expresses this through their shared skin tones; Ankhesenamun is just as sun-tanned as Tutankhamun. The red used in this composition also represents vitality and the energy of their relationship. The couple's hair is blue, symbolizing fertility, life, and rebirth while their clothing is white, representing purity. The background is gold, the color of the gods, and all of the intricate details, including the crowns the figures wear and their colors, all have their own specific meaning and go to tell the story of the featured couple.

A sword or a cosmetic case was designed and created with this same goal in mind: story-telling. Even the garden of a house told a story: in the center was a pool surrounded by trees, plants, and flowers which, in turn, were surrounded by a wall and one entered the garden from the house through a portico of decorated columns. All of these would have been arranged carefully to tell a tale which was significant to the owner. Although Egyptian gardens are long gone, models made of them as grave goods have been found which show the great care which went into laying them out in narrative form.

In the case of the noble Meket-Ra of the 11th Dynasty, the garden was designed to tell the story of the journey of life to paradise. The columns of the portico were shaped like lotus blossoms, symbolizing his home in Upper Egypt, the pool in the center represented Lily Lake which the soul would have to cross to reach paradise, and the far garden wall was decorated with scenes from the afterlife. Every time Meket-Ra would sit in his garden he would be reminded of the nature of life as an eternal journey and this would most likely lend him perspective on whatever circumstances might be troubling at the moment.

Techniques

The paintings on Meket-Ra's walls would have been done by artists mixing colors made from naturally occurring minerals. Black was made from carbon, red and yellow from iron oxides, blue and green from azurite and malachite, white from gypsum and so on. The minerals would be mixed with crushed organic material to different consistencies and then further mixed with an unknown substance (possibly egg whites) to make it sticky so it would adhere to a surface. Egyptian paint was so durable that many works, even those not protected in tombs, have remained vibrant after over 4,000 years.

Although home, garden, and palace walls were usually decorated with flat two-dimensional paintings, tomb, temple, and monument walls employed reliefs. There were high reliefs (in which the figures stand out from the wall) and low reliefs (where the images are carved into the wall). To create these, the surface of the wall would be smoothed with plaster which was then sanded. An artist would create a work in minature and then draw grid lines on it and this grid would then be drawn on the wall. Using the smaller work as a model, the artist would be able to replicate the image in the correct proportions on the wall. The scene would first be drawn and then outlined in red paint. Corrections to the work would be noted, possibly by another artist or supervisor, in black paint and once these were taken care of the scene was carved and painted.

Paint was also used on statues which were made of wood, stone, or metal. Stonework first developed in the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt and became more and more refined over the centuries. A sculptor would work from a single block of stone with a copper chisel, wooden mallet, and finer tools for details. The statue would then be smoothed with a rubbing cloth. The stone for a statue was selected, as with everything else in Egyptian art, to tell its own story. A statue of Osiris, for example, would be made of black schist to symbolize fertility and rebirth, both associated with this particular god.

Metal statues were usually small and made of copper, bronze, silver, and gold. Gold was particularly popular for amulets and shrine figures of the gods since it was believed that the gods had golden skin. These figures were made by casting or sheet metal work over wood. Wooden statues were carved from different pieces of trees and then glued or pegged together. Statues of wood are rare but a number have been preserved and show tremendous skill.

Cosmetic chests, coffins, model boats, and toys were made in this same way. Jewelry was commonly fashioned using the technique known as cloisonne in which thin strips of metal are inlaid on the surface of the work and then fired in a kiln to forge them together and create compartments which are then detailed with jewels or painted scenes. Among the best examples of cloisonne jewelry is the Middle Kingdom pendant given by Senusret II (c. 1897-1878 BCE) to his daughter. This work is fashioned of thin gold wires attached to a solid gold backing inlaid with 372 semi-precious stones. Cloisonne was also used in making pectorals for the king, crowns, headdresses, swords, ceremonial daggers, and sarcophagi among other items.

Conclusion

Although Egyptian art is famously admired it has come under criticism for being unrefined. Critics claim that the Egyptians never seem to have mastered perspective as there is no interplay of light and shadow in the compositions, they are always two dimensional, and the figures are emotionless. Statuary depicting couples, it is argued, show no emotion in the faces and the same holds true for battle scenes or statues of a king or queen.

These criticisms fail to recognize the functionality of Egyptian art. The Egyptians understood that emotional states are transitory; one is not consistently happy, sad, angry, content throughout a given day much less eternally. Artworks present people and deities formally without expression because it was thought the person's spirit would need that representation in order to live on in the afterlife. A person's name and image had to survive in some form on earth in order for the soul to continue its journey. This was the reason for mummification and the elaborate Egyptian burial rituals: the spirit needed a 'beacon' of sorts to return to when visiting earth for sustenance in the tomb.

The spirit might not recognize a statue of an angry or jubilant version of themselves but would recognize their staid, complacent, features. The lack of emotion has to do with the eternal purpose of the work. Statues were made to be viewed from the front, usually with their backs against a wall, so that the soul would recognize their former selves easily and this was also true of gods and goddesses who were thought to live in their statues.

Life was only a small part of an eternal journey to the ancient Egyptians and their art reflects this belief. A statue or a cosmetics case, a wall painting or amulet, whatever form the artwork took, it was made to last far beyond its owner's life and, more importantly, tell that person's story as well as reflecting Egyptian values and beliefs as a whole. Egyptian art has served this purpose well as it has continued to tell its tale now for thousands of years.

![Narmer Palette [Two Sides]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/4412.jpg?v=1700078649)