Schooldays (c. 2000 BCE) is a Sumerian poem describing the daily life of a young scribe in the schools of Mesopotamia. The work takes the form of a first-person narration and dialogue in relating the challenges the student faces and how he resolves them by having his father bribe his teacher with expensive gifts.

The poem (also known as Sumerian School Days, Edubba A, and Diary of a Scribe) was popular reading as evidenced by the over 21 copies, and fragments of others, that have been found throughout the region that was once Mesopotamia, especially in Iraq and Syria, the most complete tablet coming from the ruins of ancient Nippur, modern-day Iraq. Whatever the original purpose of the composition was, it became part of the curriculum of the Sumerian scribal school known as the edubba ("House of Tablets") and was copied and memorized as one of the more difficult texts to master prior to graduation.

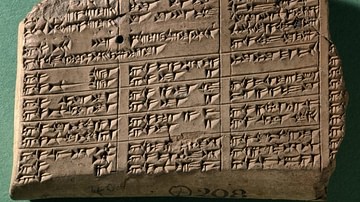

Students progressed in classes from the early stage of simply learning how to make clear wedge-shaped characters of cuneiform script in clay to work with more difficult texts known as the Tetrad (groups of four compositions) then the Decad (groups of ten), and finally to the most complex works, which included pieces such as A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe (also known as Edubba C), The Debate Between Sheep and Grain, and others including Schooldays (a modern-day title for the work). The satirical tone and detail of Schooldays has led to comparisons with A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe, which is also interpreted as satire.

Although the text was discovered earlier, the largest fragment was first translated in 1909. The nearly complete text, as given below, was not translated until 1949. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer, in his History Begins at Sumer, describes the work as "the first case of apple-polishing" on record as the focus of the work shifts midway from the trials of the student in his daily life at school to his resolution of the problem by inviting his teacher to his home for dinner and lavish gifts. The piece ends with the teacher, who had previously beaten the student for various infractions of the rules and laziness in his work, praising him as a scholar and promising him better treatment in the future, even though there is no evidence the student plans on changing any of his habits.

Summary & Commentary

At the Sumerian scribal school, students as young as 8 years old would begin their education in mastering cuneiform script as well as the various fields of knowledge they would be expected to write about, ranging from mathematics and accounting to botany, agricultural and tax records, literature, religion, and other subjects. The students were almost uniformly male, although girls from prestigious families were allowed to attend if their parents wanted them to become doctors, priestesses, or participate in the family business at the highest levels. Kramer comments:

The original goal of the Sumerian school was what we would term "professional" – that is, it was first established for the purpose of training the scribes required to satisfy the economic and administrative demands of the land, primarily those of the temple and palace. (History, 4)

As cuneiform script had over 600 characters which needed to be imprinted clearly in the moist clay that served as writing tablets, students were expected to devote themselves completely to their studies each day, practice at home every night, and be prepared to deliver their homework flawlessly to the teacher the next day. In the course of a school day, furthermore, students were expected to follow the rules set down by the headmaster or "school father" as these rules were designed to encourage personal discipline and general order. If one failed to produce work in clear copy (a "good hand") or broke any of these rules, one was caned – which most likely meant a beating across the backside and legs with a stout stick – but, by any definition, meant corporal punishment.

According to Kramer, Schooldays was written by a teacher at one of these schools, perhaps at Nippur, as a satire on how a wayward and lazy student might finally resolve his conflict with his primary instructor. The piece begins with the author/teacher asking the student, "Where did you go from the earliest days?", in other words, "What did you do from the time you were young?" The student's answer begins the action of the story.

The student relates how he went to school each day, ate the lunch prepared for him by his mother, tended to his studies, and returned home to recite his lessons for his father and receive praise. The significance of lines 9-12 is that education was not compulsory but voluntary and one's father paid for one's tuition and school supplies. To make sure this money was well spent, it seems (from this work and other sources), a student would recite the lessons of the day for the head of the household each evening upon returning from school.

The anxiety of the student over possibly being late for school (and caned for the offense) is expressed in lines 15-17 and, as soon as he arrives that morning, he is reprimanded for tardiness and then caned for submitting shoddy work. Lines 30-47 detail the student's trials in being caned throughout the day for various infractions including talking in class instead of studying, getting up from his seat without permission, and leaving the grounds without asking leave.

All of these punishments are administered by different teachers – the master of cuneiform (drawing), of the Sumerian language, of "the gate" (presumably meaning a kind of truant officer) - but would have been approved by the "school father" who presided over the education of the student population and would be understood as this student's primary teacher. The student becomes so discouraged by the beatings, he wants to quit school ("I forsook the scribal art", line 48). In line 53, however, he decides upon a plan and suggests it to his father: they will try to get on the teacher's good side by inviting him to dinner as an honored guest and bribing him with gifts.

The rest of the poem relates how the teacher accepts the invitation and is placed in the seat of honor at dinner. He is served by the student (who also recites his lessons flawlessly for the room) and is flattered by the father who then presents him with expensive clothing and a ring. The teacher, overjoyed at receiving "a gift over and above my earnings" (line 81), not only forgives the student for any lapses but promises him he will "rank the highest of [all] the schoolboys" (line 88) in the future. The student's success in school is assured, and the poem ends with praise for Nisaba (given here as Nidaba, another version of her name), the Sumerian goddess of writing and accounts, who was traditionally praised at the end of compositions.

Text

The following translation is by Samuel Noah Kramer from his article Schooldays: A Sumerian Composition Relating to the Education of a Scribe as cited by World History Commons online site and supplemented by Kramer's History Begins at Sumer and The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Line numbering absent in the original has been added below for clarification. Ellipses indicate missing words or lines.

1."Schoolboy, where did you go from earliest days?"

"I went to school."

"What did you do in school?"

"I read my tablet, ate my lunch,

5. prepared my tablet, wrote it, finished it; then

my prepared lines were prepared for me

(and in) the afternoon, my hand copies were prepared for me.

Upon the school's dismissal, I went home,

Entered the house, (there) was my father sitting.10. I spoke to my father of my hand copies, then

Read the tablet to him, (and) my father was pleased;

Truly I found favor with my father."

[I said] "I am thirsty, give me drink,

I am hungry, give me bread,

15. Wash my feet, set up the bed, I want to go to sleep;

Wake me early in the morning,

I must not be late, (or) my teacher will cane me."

When I awoke early in the morning,

I faced my mother, and

20. Said to her: "Give me my lunch, I want to go to school."

My mother gave me two rolls, I left her;

My mother gave me two rolls, I went to school.

In the tablet-house, the monitor said to me:"Why are you late?" I was afraid, my heart beat fast.

25. I entered before my teacher, took (my) place.

My "school-father" read my tablet to me,

[he said] "The ... is cut off," caned me.

I ... to him lunch ... lunch.

The teacher in supervising the school duties,

30. Looked into house and street in order to pounce upon someone, [he said] "Your ... is not ...," caned me.My "school-father" brought me my tablet.

What was in charge of the courtyard said, "Write," ... a peaceful place.

I took my tablet, ...

35. I write my tablet, ... my...

Its unexamined part my... does not know.

Who was in charge of ... [said] "Why, when I was not here, did you talk?" caned me. Who was in charge of the ... [said] "Why, when I was not here, did you not keep your head high?" caned me.

40. Who was in charge of drawing [said] "Why, when I was not here, did you stand up?" caned me.

Who was in charge of the gate [said] "Why, when I was not here, did you go out?" caned me.

Who was in charge of the ... [said] "Why, when I was not here, did you take45. the ...?" caned me.

Who was in charge of the Sumerian [said] "You spoke ...," caned me.

My teacher [said] "Your hand is not good," caned me.

I neglected the scribal art, [I forsook] the scribal art,

My teacher did not ...,

50. ... d me his skill in the scribal art.

The ... of words, the art of being a young scribe,

the ... of the art of being a big brother, let no one ... to school."

[I said to my father] "Give me his gift, let him direct the way to you,

let him put aside counting and accounting;

55. the current school affairs the schoolboys will ..., verily they will ... me."

To that which the schoolboy said, his father gave heed.

The teacher was brought from school;

having entered the house, he was seated in the seat of honor.

The schoolboy took the ..., sat down before him;

60. whatever he had learned of the scribal art,

he unfolded to his father.

His father, with joyful heart

says joyfully to his "school-father":

"You 'open the hand' of my young one, you make of him an expert,65. show him all the fine points of the scribal art.

You have shown him all the more obvious details of the tablet-craft, of counting and accounting,

You have clarified for him all the more recondite details of the ... Pour out for him ... like good wine, bring him a stand,

70. make flow the good oil in his ...-vessel like water,

I will dress him in a [new] garment, present him a gift, put a band [a ring] about his hand."

They pour out for him ... like good date-wine, brought him a stand,

made flow the good oil in his ...-vessel like water,

75. he dressed him in a [new] garment, gave him a gift, put a band about his hand.

The teacher with joyful heart gave speech to him:"Young man, because you did not neglect my word, did not forsake it,

May you reach the pinnacle of the scribal art, achieve it completely.

80. Because you gave me that which you were by no means obliged (to give),

you presented me with a gift over and above my earnings, have shown me great honor,

may Nidaba, the queen of the guardian deities, be your guardian deity,

may she show favor to your fashioned reed,

85. may she take all evil from your hand copies.

Of your brothers, may you be their leader,

Of your companions, may you be their chief,

May you rank the highest of (all) the schoolboys,... who come from the royal house.

90. Young man, you "know" a father, I am second to him,

I will give speech to you, will decree [your] fate:

Verily your father and [mother] will support you in this matter,

As [that] which is Nidaba's, as that which is thy god's, they will present offerings and prayers to her;

95. the teacher, as that which is your father's verily will pay homage to you;

in the ... of the teacher, in the ... of the big brother,

your ... whom you have established,

your manly [kinfolk] verily will show you favor.

You have carried out well the school duties, have become a man of learning.100. Nidaba, the queen of the place of learning, you have exalted.”

O Nidaba, praise!

Conclusion

The "big brother" mentioned in the poem was the title of older students who would serve as teaching assistants to the professors and so line 96, following the rest of the teacher's praise, suggests that the young student will now be honored even by those more advanced than he. The teacher's effusive praise of his formerly tardy and poorly prepared student, only after he has been given the grandest treatment and fine gifts, marks the piece clearly as satire even if one misses earlier details.

As with A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe, Schooldays would have been memorized, copied, and recited either before one's teacher or before one's class, prior to graduation. The piece was most likely written to provide some light-hearted work and recitation to balance out some of the other advanced texts which dealt with weightier matters, such as The Curse of Agade or Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld.

Although understood as satire, Schooldays – like A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe – is considered an accurate representation of the life of a Sumerian student and teacher in the 2nd millennium BCE. Scholars routinely note the lines pertaining to corporal punishment for breaking the rules of the edubba, the difficulty of mastering the scribal art, and how teachers were paid so poorly they could not afford luxuries such as new clothes or jewelry, as corresponding to what is known of the reality of the educational system of ancient Mesopotamia.

Kramer describes the poem as "one of the most human documents ever excavated in the Near East" and notes how "its simple, straightforward words reveal how little human nature has really changed throughout the millenniums" (History, 10). The poem remains as relatable to an audience in the present day as it was over 4,000 years ago and continues to be just as popular. In ancient Mesopotamia, it was copied repeatedly by hand to share with others; today it is frequently anthologized. In either era, it speaks clearly to the same human impulses and desires.