King Sejong the Great (15 May 1397 to 8 April 1450 CE) ruled Korea from 1418 to 1450 CE as the fourth king of the Joseon Dynasty (also spelled Choson). One of only two Korean kings called 'the Great' today, Sejong had a major impact on Korea and Koreans. His greatest achievement was creating Hangul, the Korean alphabet, but his patronage of science, technology, literature, and medicine all had a large impact on Korea and Koreans.

Rise to the Throne

Sejong, born as I Do, had an unusual path to the Joseon throne. He was the third son of King Taejong, which put him third in line at birth. However, his father favored him as opposed to his older sons, Yangnyeong and Hyoryeong. Yangnyeong was removed from succession, either voluntarily abdicating the title of prince or having it removed by his father; historians are not yet sure which is true.

Taejong's second son, Hyoryeong, took up life in a monastery after Yangyeong's removal as prince, leaving Sejong to be the heir. This was further solidified when a group of 15 subjects brought forth a petition (Gongnon in Korean) to King Taejong. They proposed that the most virtuous member of the royal family should receive the prince's crown instead of the person next in the line of succession, which would have been Yangyeong's first-born son.

King Taejong accepted this petition, and he gave Sejong the title of prince and heir to the throne. Sejong's rise to king was complete when Taejong retired to allow his son to rule in 1418. However, Taejong continued to influence both the court and the new king until his death in 1422. After his father's death, Sejong left a legacy in everything from military campaigns, scientific advances, and literature to medicine, time-keeping, and cartography. As a ruler, Sejong grounded his decisions and policies in Confucian thought, suppressing Korean Buddhism and Islam in the process.

Military Campaigns

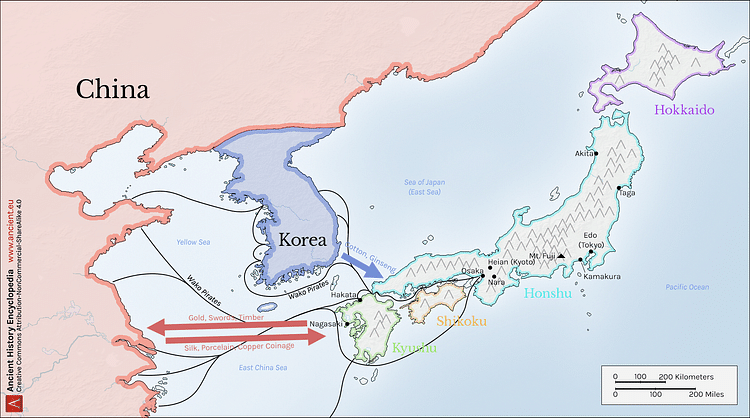

Sejong's father, Taejong, and grandfather Taejo expanded the borders of the young Joseon Dynasty by repelling the last Mongols off the Korean peninsula and fighting back Japanese wako pirates from the island of Tsushima. Sejong worked to solidify these newly expanded borders and oversaw the Gihae Eastern Expansion (called the Ōei Invasion in Japanese sources) to quell the pirates from Tsushima once and for all.

The Gihae Expansion was successful, with the Sō rulers of Tsushima surrendering to Sejong in 1419. Tsushima – known as Daemado in Korean – then became a territory of the Joseon Dynasty, a claim which Korea made until 1951. Although the pirate attacks did not completely disappear, the raids of Korean ships and land were greatly suppressed. With the main militaristic threats of Korea dealt with, Sejong turned his head to more humanistic ventures.

Science & Technological Advances

Sejong quickly saw a need for resident scientists in his court, and two years after becoming king, in 1420, he created the Hall of Worthies (Jiphyeonjeon). The Hall of Worthies acted both as advisors to the king and as an academic research engine. Many of the inventions and scientific writings from Sejong's reign came from the scientists he appointed to the Hall of Worthies.

King Sejong inherited his father's advancements in moveable type printing and expanded its capacity to become the leading East Asian nation in printing at the time. While the Chinese ignored this new technology, the Joseon Koreans embraced it and increased printing speeds by 20 times upon finalizing the design in 1434. This increased capacity for printing would help Sejong publish and circulate his other scientific and medical advancements throughout his reign.

Other technological advances patronized by Sejong included devices to measure meteorological events. Sejong oversaw the invention of rain gauges and water marks as a way to objectively measure and record the rainfall in different parts of the kingdom. The invention of a device for measuring wind speed and direction with a cylindrical cloth added an extra layer of data for Sejong-era scientists.

To further astronomical knowledge, Sejong ordered the building of an observatory platform in the royal Gyeonbok Palace, where state-of-the-art instruments were available for scientists to use. Other inventions of the time include a portable sundial with a built-in compass and a precise water clock. The water clock was invented by Jang Yeong-Sil, who was born a peasant, but Sejong noticed his scientific ability and creativity and offered to bring him to court and pay him to work on inventions.

Cartography was another science Sejong supported. With the addition of land taken from the Japanese and Mongols by his grandfather, father, and the Gihae Expansion, Korean maps needed updating. Sejong's cartographers used astronomical observations measured with new inventions to create maps which, even today, are exceptionally accurate. Scientists also moved the prime meridian on their maps to Seoul, the capital, instead of Beijing or Nanjing, the Chinese capitals of the time. This allowed the maps of Korea to be much more accurate than before.

A final major area of advancement under Sejong was agriculture. Sejong instructed his scientists to compile an agricultural book, the Nongsa Jikseol. This book included descriptions of materials and best practices from all the regions of Korea. Sejong wanted to help Korean farmers learn the best ways to enhance crop yield. Further, Sejong revamped taxes for farmers so that in poor crop years the farmers would pay less in taxes. This allowed them to focus on growing their food for the kingdom.

Social Advances

In addition to reforming taxes for farmers (called Gongbeop), Sejong dispatched aides and ministers throughout Korea to gauge his people's opinions on the new system before implementation – a 17-year process of surveying the public and debating with high ministers. After the population and the ministers agreed the new progressive tax system was better than the original Jo-Yong-Jo system implemented about 400 years earlier by the Goryeo Dynasty, Sejong finally implemented the tax reform. This back-and-forth of survey and debate before implementing a new taxation system shows Sejong's benevolence towards his subjects and desire for a better Korea.

Illustrated by the tax reform, Sejong ruled and wrote laws in accordance with Confucian ideals. He believed that laws needed to fit with the will and belief of the people, that they needed to be followed by the king as well as the people, and that they could not be amended or abolished without due debate.

Medical Advances

Sejong, initially using his father's list of issues in Korea's medical system, advanced both the study of medicine and the distribution of health services to the population. The first change Sejong made was to reorganize Korea's healthcare system. He introduced different offices that focused on one class only, as opposed to the former system which was in charge of all care for all classes. One office provided medical care to the royal family; another office provided care to high-ranking officials, and another provided care to other officials. The general populace received their care from more localized offices.

This revamped healthcare system represented the bureaucratic system in the Joseon period, with the king and royal family on top, followed by advisors and ministers, then officials. Sejong also stressed the delivery of medicine to the general population more than previous kings and made healthcare more affordable by instructing state medical programs to source local ingredients and drive the cost of medicine down.

Sejong also reformed medical research and training. He created a group of scholars dedicated to studying medical texts of China, hand-picked from people passing the civil service entrance exam (the Gwageo). In 1433, Sejong and his Hall of Worthies published the Hyangyak Jipseongbang, a text which compiled all medical knowledge in Korea with an emphasis on local ingredients and knowing the limitations of those ingredients. This was a move towards native Korean medicine as opposed to importing Chinese traditional medicine as before. In 1445 a further encyclopedia of medical knowledge and recipes, the Uibang Yuchwi, was published.

Hangul – The Korean Alphabet

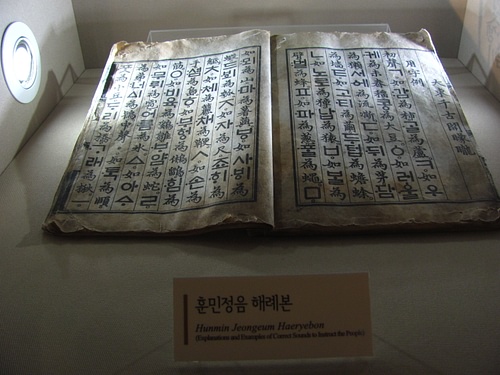

Even with many other advances, Sejong's biggest legacy is the creation and introduction of the Korean language's native alphabet, Hangul (called Chosongul in North Korea, meaning "Joseon Writing"). Historians are not sure when exactly Sejong began developing the alphabet, but he finalized it in 1443 and published it in 1446 as the Hunmin Jeongeum.

Before introducing Hangul, the Korean language was written with Classical Chinese characters, abridged with notes to account for the differences in languages. (Korean and Chinese, while both languages of East Asia, are not related). This meant that only those able to afford education – the ruling and upper classes – could read and write. Sejong wanted to change this so that even peasants could learn to read and write within days – much to the opposition of the elite classes.

Hangul is an alphabet where each of the 28 (currently 24) letters represents either a consonant or a vowel. Sejong designed the consonants to roughly mimic the position of the mouth and tongue when saying each letter, making it easy for Koreans to learn to read and write using Hangul. To form words, the letters are arranged in syllable blocks, so that each syllable of a word is one block of two to four letters.

For example, Sejong's name has two syllables, "Se" and "jong". The letters of his name, in order, are: ㅅ (s), ㅔ (e), ㅈ (j), ㅗ (o), ㅇ (ng, one letter in Korean). His first syllable is, therefore, 세, and the second syllable is 종. Together, his name in Hangul is 세종 (Se-jong).

The ease with which Hangul could be learned by anyone scared Sejong's high ministers and advisors. The ability of peasants to read and write threatened their families' positions in the court, as it increased the pool of potential civil servants. After Sejong's death, the elite classes restricted its use. It lived on, however, through fiction writings and women's use of it to communicate with members of their family back home while they were off at court.

After being prohibited under Japanese occupation in the early 1900s, much of the Korean population adopted the alphabet as a symbol of independence and nationalism. Upon independence from Japan in 1946, the country adopted Hangul as the official script of the Korean language, 500 years after its initial publication.

Legacy

Sejong died in 1450 after ruling for 32 years. His reign saw unparalleled scientific and technological advancement in Korea and brought about a period of political stability. While the Joseon Dynasty ruled Korea from 1392 to 1897, Sejong is remembered as one of the most important rulers of the period. His greatest achievement was creating Hangul, the Korean alphabet, but his patronage of science, technology, literature, and medicine all had a large impact on Korea and Koreans. So much so that South Korea's new administrative center, Sejong City, is named after him.