Seleucus I Nicator (l. c. 358-281 BCE, r. 305-281 BCE) was one of the generals of Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) who make up the group of Diadochi ("successors") who divided the vast Macedonian Empire between them after Alexander's death in 323 BCE (the others being Cassander, Ptolemy, and Antigonus). Despite not receiving his share of the fallen king's empire until several years later, Seleucus I Nicator (meaning "unconquered" or "victor") was one of the more capable of the successors to Alexander's empire. Seleucus and his descendants established what became known as the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) which lasted nearly 250 years.

Early Life of Seleucus

As with the other successors to Alexander, Seleucus was the son of a Macedonian nobleman, one of King Phillip II's generals. While little else of his family is known, historians do speak of a dream his mother had in which he was fathered not by Antiochus but by the Greek god Apollo. In the dream she received a unique ring inscribed with the symbol of an anchor. According to the legend, Seleucus was born with the same anchor symbol in the form of a tattoo on his thigh. This oddity of birth led him to later lay claim to a divine kingship; however, some believe the entire story is a concoction, and he simply wished to emulate Alexander's similar claim to divinity. Even though his relationship to Alexander is not fully known (he may or may not have been a close companion), Seleucus followed the young Macedonian king's quest to conquer the Persian Empire and defeat Darius III (r. 336-330 BCE) in a number of engagements, finally conquering the Achaemenid Persian Empire by 330 BCE.

The only certainty concerning Seleucus I's role in the Persian campaign is that he was one of the commanders of the hypaspists - the silver shields. This elect guard served as a buffer between the cavalry and infantry – a kind of elite police force. Each member of the hypaspists was carefully chosen on an individual basis not only for their social standing (there were regular and royal hypaspists) but also for their physical strength and bravery. The hypaspists were known for their adept mobility and often used on special missions in rugged terrain as well as in situations that called for hand-to-hand combat.

Little of Seleucus' presence is mentioned in ancient sources until the Battle of Hydaspes (326 BCE) against King Porus of India. Prior to the battle, as Alexander and his forces crossed the Hydaspes River and prepared to meet the Indian king and his elephants, Alexander changed his normal defensive alignment. He stationed his archers (over 1,000) ahead of his Companion cavalry – this served as a screen against the elephants; they were followed by the infantry, the remaining cavalry, and lastly Seleucus and his hypaspists. Alexander's deployment was sound; he had wanted to avoid putting his cavalry directly against the elephants. Luckily for Alexander and his men, the elephants proved ineffective, actually doing more harm to the Indians than the Macedonians.

As Alexander had moved across Asia battling the Persians from Granicus (334 BCE) through Issus (333 BCE) and Gaugamela (331 BCE), he had hoped to unite the two worlds, spreading Hellenistic culture. Hydaspes, however, proved to be Alexander's last major conflict; he would and could go no further. After defeating King Porus in India, his men balked at going any further. Despite his plans, Alexander was forced to return to Babylon. While there he had to come to terms with rebellions, not only by the Persian provinces but also many of his own men. They resented the presence of Persians within the army and being forced to take Persian wives. (Only Seleucus kept his Persian wife, Apama). Alexander died in 323 BCE before many of these problems could be resolved.

Alexander's Death

While Seleucus's name does not appear among those who chose to rebel against Alexander, it is mentioned just prior to the death of Alexander. The question arose among his generals– what to do with the body of the fallen king if he dies. The historian Plutarch in his The Life of Alexander mentions Seleucus only one time when he wrote: “It was also on this day that Python and Seleucus were sent to the sanctuary of Sarapis to ask if they should bring Alexander there, but the god told them to leave him where he was. And then he died late in the afternoon of the twenty-eighth.”

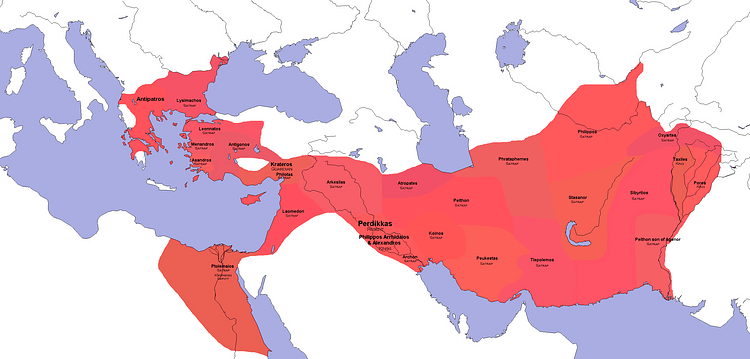

The Successor Wars

The reason for Ptolemy's desire to divide the empire was a selfish one, for he achieved a long time goal and acquired Egypt. While he proved to be a capable “pharaoh,” one of his first acts was to kidnap the body of Alexander and bring him to Egypt. Perdiccos, who saw himself as the true successor to Alexander, had planned to ship the king's body to Macedonia where a tomb was being constructed; however, Ptolemy stole the body as it arrived in Damascus. This action led to an immediate and lengthy war between Peridiccos and Ptolemy. Although he served as an officer under Perdiccos and at first sided with him, Seleucus turned against him and aligned himself with Ptolemy. Some historians even believe he took part in Peridiccos' assassination. As a reward for his assistance, Seleucus was named governor of Babylon by Antipater.

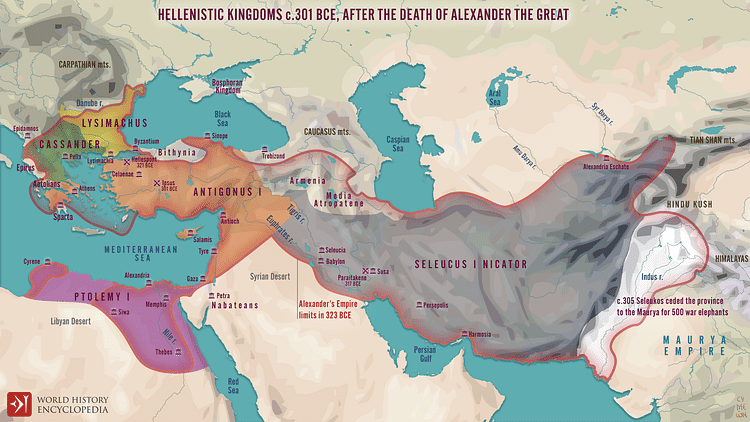

Because of jealousy and ambition among the other successors, Seleucus was unable to maintain his province's borders, and when Antigonos the One-Eyed invaded Babylon, Seleucus fled to Egypt in 316 BCE, seeking assistance and refuge from Ptolemy. In 312 BCE, and with the assistance of Ptolemy, Cassander and Lysimander, Seleucus was able to defeat Antigonos in the Battle of Gaza and regain his lost territory.

Seleucus' Empire

Over the next few years, he assisted in the defeat and death of Antigonos at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE, expanding his empire into Syria. Later, he captured the son of Antigonos, Demetrios, and held him prisoner until Demetrios' death in 285 BCE. Likewise, Seleucus proved himself to be a capable general and strategist in his own right; he expanded his own territory into Asia Minor and India, making peace and securing his southern border with the Indian ruler Chandraguta.

He built the cities of Antioch (his new capital) and Seleucia located on the Tigris River. At the Battle of Corupedium, he defeated and killed Lysimachos, setting his eyes on Macedonia; however, he never succeeded in his conquest, dying in his attempt, killed by the son of his former ally, Ptolemy, who had wanted Macedonia for himself. Seleucus's memory would survive long after him, for his family established an empire that would live for generations to come.