Serapis is a Graeco-Egyptian god of the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) of Egypt developed by the monarch Ptolemy I Soter (r. 305-282 BCE) as part of his vision to unite his Egyptian and Greek subjects. Serapis’ cult later spread throughout the Roman Empire until it was banned by the decree of Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE).

Some form of the god existed prior to the Ptolemaic Period and may have been the patron deity of the small fishing and trade port of Rhatokis, later the site of the city of Alexandria, Egypt. Serapis is referenced as the god Alexander the Great invoked at his death in 323 BCE, but whether that god – Sarapis – is the same as Serapis has been challenged as it is thought more likely Sarapis was a Babylonian deity.

Serapis was a blend of the Egyptian gods Osiris and Apis with the Greek god Zeus (and others) to create a composite deity who would resonate with the multicultural society Ptolemy I envisioned for Egypt. Serapis embodied the transformative powers of Osiris and Apis – already established through the cult of Osirapis, which had joined the two – and the heavenly authority of Zeus. He was therefore understood as Lord of All from the underworld to the ethereal realm of the gods in the sky.

The cult of Serapis spread from Egypt to Greece and was among the most popular in Rome by the 1st century CE. The cult remained a powerful religious force until the 4th century CE when Christianity gained the upper hand. The Roman emperor Theodosius I proscribed the cult in his decrees of 389-391 CE, and the Serapeum, Serapis’ cult center in Alexandria, was destroyed by Christians in 391/392 CE, effectively ending the worship of the god.

Ptolemy I & Serapis

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, his generals divided and fought over his empire during the Wars of the Diadochi. Ptolemy I took Egypt and established the Ptolemaic Dynasty, which he envisioned as continuing Alexander’s work of uniting different cultures harmoniously. Egypt had been controlled by the Persians, except for brief periods, from 525 BCE until Alexander took it in 332 BCE, and they welcomed him as a liberator. Alexander had hoped to blend the cultures of the regions he conquered with his own Hellenism, but the Greeks and Egyptians were still observing the traditions of their own cultures at the time of his death. Ptolemy I made a fusion of these cultures among his top priorities and focused on religion as the means to that end.

The Egyptians still worshipped the same gods they had for thousands of years, and Ptolemy I recognized they were unlikely to accept a new deity, so he took aspects from two of the most popular gods – Osiris and Apis – and blended them with the Greek king of the gods, Zeus, drawing on the already established Egyptian cult of Osirapis, to create Serapis. The historian Plutarch (l. c. 45/46-120/125 CE) describes Serapis’ creation and the establishment of his cult center at Alexandria:

Ptolemy Soter saw in a dream the colossal statue of Pluto in Sinope, not knowing nor having ever seen how it looked, and in his dream the statue bade him convey it with all speed to Alexandria. He had no information and no means of knowing where the statue was situated but, as he related the vision to his friends, there was discovered for him a much-traveled man by the name of Sosibius who said that he had seen in Sinope just such a great statue as the king thought he saw. Ptolemy, therefore, sent Soteles and Dionysius, who, after a considerable time and with great difficulty, and not without the help of providence, succeeded in stealing the statue and bringing it away. When it had been conveyed to Egypt and exposed to view, Timotheus, the expositor of sacred law, and Manetho of Sebennytus, and their associates conjectured that it was the statue of Pluto, basing their conjecture on the Cerberus and the serpent with it, and they then convinced Ptolemy that it was the statue of none other of the gods but Serapis. It certainly did not bear this name when it came from Sinope but, after it had been conveyed to Alexandria, it took to itself the name which Pluto bears among the Egyptians, that of Serapis. (Moralia; Isis and Osiris, 28)

Serapis was intended to be, in Plutarch’s words, "god of all peoples in common, even as Osiris is" and the fact that a Greek (Timotheus) and an Egyptian (Manetho) agreed on the statue’s identity was taken as a sign from the god that he would assume this role. Ptolemy I built a grand temple for his worship, the Serapeum, which came to house the statue from Sinope. With Serapis at the center of religious devotion, Ptolemy I began a rigorous building program which was continued by his son and successor Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 285-246 BCE) who had co-ruled with him since 285 BCE. The great Library at Alexandria, begun under Ptolemy I, was completed by Ptolemy II, who also added to the Serapeum and finished building the Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The Composite God

Plutarch’s story of the stolen statue of Pluto has been challenged, and some scholars claim it was already a statue of Serapis taken from the Serapeum at Memphis. However that may be, the statue is understood to have been a representation of an underworld deity, either the Graeco-Roman Hades/Pluto or Serapis who, as a blend of Osiris and Apis, was also associated with the underworld.

Osiris was the dying and reviving god figure who had been killed by his brother Set and revived by his sister-wife Isis and her sister Nephthys. Once he was returned to life, however, he was found to be incomplete and so descended into the otherworld where he reigned as king and judge of the dead while his son, Horus, reigned on earth. Osiris was therefore associated with death and the afterlife but also with regeneration, rebirth, and transformation. Osiris had been a popular god in Egypt since the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) and, in time, came to be associated with Apis.

Apis was among the most important and highly regarded deities of Egypt, worshipped from the First Dynasty of Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2890 BCE) through the end of the Ptolemaic Period in 30 BCE. He was originally a fertility god who then became the herald of the great god Ptah and then Ptah incarnate. Apis was thought to incarnate himself in a bull (the Apis Bull) who was cared for and venerated, as any embodiment of the divine was, for 25 years when, if it was not diseased or had not suffered some serious accident, was ceremonially sacrificed. While it had lived it had embodied Ptah and, in death, was linked to Osiris, and this belief led to the development of the cult of Osirapis.

Ptolemy I took this established cult and added the Greek god Zeus to it. Zeus was the king of the Olympian gods, often referred to as Father, and understood as the god of thunder as well as cosmic justice. Zeus was recognized as the deity who had established order and maintained it both for humans and immortals and was also the father of many of the best-known deities of the ancient Greek pantheon such as Apollo and Artemis, Hermes, Persephone, and the Nine Muses, among others. Serapis not only embodied these three gods, however, but drew on others associated with the sun, afterlife, earth energy, and healing. Scholar Richard H. Wilkinson comments:

The hybrid god Serapis was a composite of several Egyptian and Hellenistic deities introduced at the beginning of the Ptolemaic Period in the reign of Ptolemy I. The god thus answered the needs of a new age in which Greek and Egyptian religion were brought face to face and the new deity was created to form a bridge between the two cultures. Linguistically, the god’s name is a fusion of Osiris and Apis, and a cult of Osirapis had in fact existed in Egypt before the rule of Ptolemies, but to this Egyptian core were added a number of Hellenistic deities which predominated in the god’s final form. Zeus, Helios, Dionysus, Hades, and Asclepius all added aspects of their respective cults, so that Serapis emerged as a thoroughly Egypto-Hellenistic deity who personified the aspects of divine majesty, the sun, fertility, the underworld and afterlife, as well as healing. The mythology of Serapis was, therefore, the mythology of his underlying deities, but the aspects of afterlife and fertility were always primary to his nature. The consort of Serapis was said to be Isis, the greatest Egyptian goddess in Hellenistic times. (127-128)

Isis was not only considered the greatest goddess in the later periods of Egyptian history but had been for thousands of years before. Isis’ association with Serapis was simply a development of her already-established link with her husband-brother Osiris but, politically and culturally, helped to boost Serapis’ standing. Isis was so popular that, by the time of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) she was the only deity worshipped by all the people of Egypt, and the other gods were understood as aspects of the one goddess.

Worship & Iconography

Temples dedicated to Serapis were constructed throughout Egypt, all seemingly based on his central cult center of the Serapeum of Alexandria. The Alexandrian Serapeum was modeled on the Serapeum at Memphis where the original statue may have been taken from, and the others that were built were smaller versions of the one at Alexandria. Scholar Geraldine Pinch comments:

The Ptolemies undertook massive temple rebuilding programs to legitimize their rule in the eyes of the Egyptians and their gods. Native Egyptian society was more temple centered than ever, and the priesthood became the custodians of Egyptian culture. Working for a temple was virtually the only form of advancement available to talented Egyptians…Yet this was not a period of decadence. Egyptian art, literature, and theology continued to flourish and develop. (37)

The priests focused the type of devotion previously shown to many deities – such as Amun, Ra, Osiris, Isis, Hathor, and Bastet – on Serapis alone who embodied the same power, grace, and responsibilities as these others. An example of this is the area of temples known as mammisi (birth house) which were formerly associated with the goddess Hathor and god Bes but now formed part of a Serapeum and were decorated with images and texts relating to the god Horus who, in this context, was an aspect of Serapis.

People would come to these temples as they always had to the homes of the gods and offer sacrifices in hopes of answers to their prayers or in thanks for those that had been heard. The priests conveyed the sacrifices to the statue of the god, as Egyptian clergy always had, and assured the people their prayers were heard. Unlike earlier Egyptian deities, however, often depicted with the heads of animals, Serapis was entirely anthropomorphic, as Wilkinson notes:

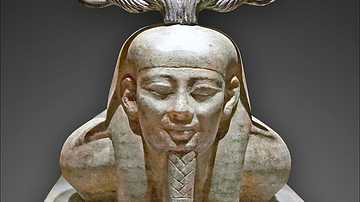

The Hellenistic elements of Serapis dominate the god’s iconography and attributes. He was portrayed in anthropomorphic form as a man wearing a Greek-style robe with Greek hairstyle and full beard and usually bearing a tall corn modius or measure on his head. In some depictions, Serapis is also given curving ram’s horns. Sometimes, as a result of the chthonic and fertility aspects of the god and his consort Isis, the two deities were depicted as serpents – one, with a beard, representing Serapis. (128)

The container on the god’s head represented abundance and fertility which, combined with his afterlife associations, linked Serapis with transformation in life and after death. From the Serapeum at Alexandria, the Ptolemies encouraged worship of Serapis throughout Egypt, but in actual practice, he was never as popular as the gods who inspired him. The cult of Isis, linked with Osiris, kept its standing, and the rituals associated with Apis remained unchanged until the end of the Ptolemaic Period. Serapis was much more popular outside of Egypt as his cult spread from the trade center at Naucratis to Greece and, later, to Rome as part of the cult of Isis.

Political Power of the Cult

Prior to Rome’s annexation of Egypt, however, Serapis retained devotees in Egypt through the reign of Cleopatra VII (51-30 BCE), the last monarch of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Even though he was not the most popular god in Egypt, he still exerted considerable power, most notably as a unifying force among the populace who recognized in the deity the attributes they venerated in their personal god of choice. His worship was encouraged by the dynasty that created him who understood the power of religion to unify people in a much deeper fashion than any political program. To this end, the government authorized the priests of Serapis to work toward empowering his cult and gaining more adherents. Scholar Alan B. Lloyd comments:

The priests enjoyed considerable political power, not least because their good will was evidently seen by the Ptolemies as the key to the acquiescence of the Egyptian population, and some of them, like Manetho of Sebennytus, played a major role in Ptolemaic cultural politics. The High Priests of Memphis were particularly important from this point of view, both because they were the most significant figures in the second city in the kingdom and because they were the supreme pontiffs of Egypt at the time, with wide-ranging contacts and influence in the country as a whole. The Ptolemies did everything they could to ensure this support. (Shaw, 407)

After the death of Cleopatra VII and the annexation of Egypt by Rome, the Serapis cult remained a potent force and traveled, via trade and military movements, to Rome.

Conclusion

From Rome, the cult spread throughout the Roman Empire as far north as Britain where evidence of the gods’ worship has been found at London and York and across North Africa to Sabratha and surrounding cities as well as to Asia Minor, notably at Ephesus. As he was linked with the afterlife and transformation, Serapis became known as a redeemer god and savior who granted believers eternal life. Correspondence during the reign of Hadrian (117-138 CE) seems to conflate references to Serapis with those of the new messiah Jesus Christ.

Some ancient writers and historians seem to have confused a reference in a letter from emperor Hadrian regarding devotees of Serapis calling themselves "Bishops of Christ" with adherents actually referring to themselves as "Bishops of the Savior", Serapis, as Christians had nothing to do with the cult of Serapis. It is also possible that Hadrian himself misunderstood or conflated worship of Serapis with that of Christ as both focused on a redeemer and the gift of eternal life after death.

The cult was still popular in the late 4th century CE when the Christian emperor Theodosius I initiated his persecution of pagan cults through a series of decrees. In 381 CE, he outlawed certain types of divination, but pagan temples were still allowed to operate more or less as they had before. Between 389 and 391 CE, however, Theodosius I made a more concerted effort to root out paganism through the Theodosian Decrees which increasingly made the practice of non-Christian rituals untenable.

In 391 CE, these decrees encouraged the anti-pagan riots in Alexandria during which images of Serapis on homes and public buildings were forcibly removed and replaced by the Christian cross despite opposition from owners or inhabitants. In the same year, or possibly 392 CE, a Christian mob inspired by the patriarch Theophilus destroyed the Serapeum in Alexandria, ending the cult of Serapis; surviving temples were later turned into churches, and Serapis was forgotten along with the other gods replaced by Christianity.