Shamanism was widely practised in Korea from prehistoric times right up to the modern era. It is a belief system which originated in north-east Asian and Arctic cultures, and although the term shamanism has since acquired a wider meaning across many different cultures, in ancient Korea it kept its original form where self-appointed practitioners promised to contact and influence the spirit world in order to assist the living. Shamans were given their authority by those who believed in their worth. As such it is not a religion, and there was no hierarchical priesthood, no texts, and no dogma to adhere to. For much of Korea's recorded history, Buddhism was the official state religion, but shamanism continued to be important to the ordinary, largely peasant population. Its influence on ancient Korean culture is most tangible in surviving art, architecture, literature, and music.

Rituals & Practitioners

In shamanism, called in Korean misin or 'superstition,' it is thought that there is another world besides that of the living, and in this spirit world there are both good and bad entities who can influence human affairs. In addition, shamanism was mixed with elements of animism, where natural features such as trees, mountains, rocks, and rivers are believed to possess their own spirits, and with the idea of geomancy, where any placement of houses, temples, and graves, for example, is carefully considered to take into account and best benefit from the location of such spirit-dwellings and life forces. A shaman, at least for believers, has the ability not only to establish contact with these spirits but to actually enter their world. Alternatively, in a kut ritual, a spirit or specific god may temporarily possess or cohabit the body of the shaman and be capable of holding a conversation. He or she does this in an altered state of consciousness or trance which is reached through prolonged chanting and dancing accompanied by drumming and bell ringing. Finally, shamans were also credited with healing powers and the ability to promote positive effects on the body such as fertility and longevity.

Female shamans were known as mudang while males were paksu or pansu, with evidence that there were many more of the former, largely because it was one of only four professions that women were allowed to pursue. To become a shaman did not require any particular ceremony, learning, or initiation. Self-appointed, shamans often claimed a spiritual experience, typically during an illness, and so practised then onwards. Daughters of mudang commonly followed their mother's footsteps and became shamans too. These shamans had no particular place or temple in which to practice their abilities but performed wherever they were needed. Some shaman shrines did exist, such as those in mountain areas dedicated to Sanshin, the Mountain God.

Shamans had no affiliation with any particular body nor any religious responsibility, believers employed them at their own risk, as it were. However, many people did believe in their ability to act as a medium between this world and the spirit realm. One group of spirits, in particular, the chosang or ancestral spirits, could be troublesome and were blamed for all manner of negative occurrences. A shaman was then employed to contact these spirits and find out the reason for their restlessness so that they might be mollified into departing from the affairs of the living.

Mudang and paksu must have had many successes for shamans are thought to have been amongst the community leaders in the early societies of ancient Korea, even perhaps to have been the single ruler. One of the terms for early Silla kings was chachaung or shaman. The possibility is further suggested by the designs of gold crowns from the 5th-6th century CE royal tombs of the Silla kingdom. These crowns have tree-like appendages, a motif commonly found in the art of shamanism, and similar to those from Siberian tribes. The contemporary Baekje (Paekche) kingdom also produced a type of branch-like adornment for their royal crowns. Korean mythology describes leaders such as the founder of the Korean race Dangun as having shamanist qualities or heritage, and he is sometimes portrayed in art as Sanshin (or vice-versa).

Coexistence with Other Religions

From the Goryeo dynasty (918 - 1392 CE) onwards, as Confucian principles and Buddhism grew in importance, shamanism diminished in terms of its influence on government and state affairs. Some queens did employ their own personal shamans and sometimes they were called on by governments in times of crisis like severe droughts or floods, but during the Joseon dynasty from the 14th century CE there were specific measures to exclude shamans from the royal court.

All shamans had to be registered, and a government official was appointed to supervise their activities. This was due to the adoption of Neo-Confucianism and a general aristocratic disapproval of shamanism with its unseemly dancing and mixes of the sexes at rituals. However, it continued to hold a strong influence over the ordinary, largely rural population, who had no qualms about accepting the validity of this and other religions from traditional ancestor worship to state-endorsed Buddhism. Indeed, folk religion had long been an eclectic mix of shamanism, animism, simplified Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism, and this is evidenced in the equally eclectic imagery seen in Korean folk art.

Shaman Art

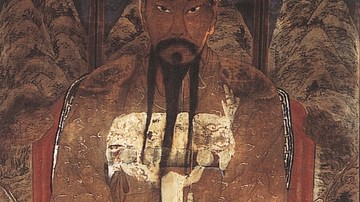

Shaman paintings, usually an artist's or even shaman's attempt to capture the experience of a kut ritual, were created on silk, paper, and cotton. They are rather primitive without any attempt to present perspective but do possess a boldness and vitality. The subject matter can be also rather limited with a small cast of gods appearing with great frequency. The Mountain God Sanshin is a favourite, and he is depicted as an old man with a long white beard, usually sitting under a pine tree and accompanied by his tiger messenger. Other popular gods include Yongwang, the Dragon King, and Haenim and Talnim, the sun and moon spirits respectively. Some gods are of Buddhist origin such as the Sambul chesok or Three Buddhas who appear on so many paper fans used by shamans in rituals.

During rituals, these paintings were hung on walls or, if outside, placed on screens or pegged to suspended lines. White, blue, and yellow are the most common colours used in such paintings. Paintings frequently incorporate elements of Buddhism, indeed Buddhist monks were tasked with painting them, and so the scenes can contain both figures of Buddha and Shaman figures like Chilseong, the Seven Star spirit, and constellations important to shamanism such as the Great Bear as well as the north pole star and nine planets. In these mixed-style paintings red is used much more than in purely shamanistic works. Another form of painting was pujok, the temporary posters pinned to doorways, walls, and chests to ward off evil spirits. These most often depicted rudimentary drawings of tigers, dogs, cockerels, and lions.

Other art forms include the shaman-influenced royal crowns of the Three Kingdoms period already mentioned and bronze star-shaped rattles or bells, also from ancient tombs, which were probably used in rituals and date to the 3rd century BCE. Shamanism influenced Buddhist architecture, notably the stone pagodas set in front of temples which sometimes had seven circular rings to represent the seven stars of the Great Bear constellation. Buddhist sculpture, too, sometimes took inspiration from shaman iconography. For example during the 11th century CE very large figures of Buddha as Maitreya (the coming Buddha) were carved out of natural boulders and many wear unique tall hats which some scholars suggest may represent a link with shamanism. Examples can be found at Paju and at the Gwanchok temple in Nonsan.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.