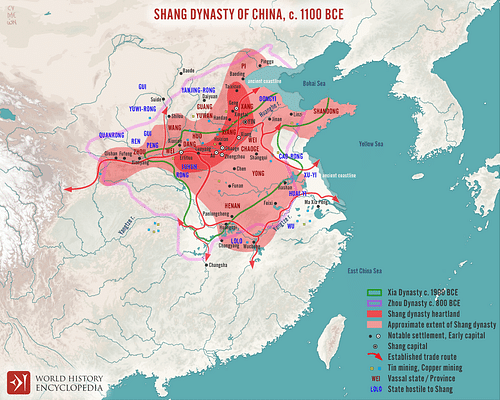

The Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) was the second dynasty of China, which succeeded the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070-1600 BCE) after the overthrow of the Xia tyrant Jie by the Shang leader, Tang. Since many historians question whether the Xia Dynasty really existed, the Shang Dynasty may have actually been the first in China and the origin of Chinese culture.

The stability of the country during the Shang Dynasty led to numerous cultural advances such as industrialized bronze casting, the calendar, religious rituals, and writing. The first king, Tang, instantly began to work for the people of his country instead of for his own pleasure and luxury and provided a role model for his successors. These men created a stable government, which would continue for 600 years, but eventually, according to the records of the Chinese historians, they lost the Mandate of Heaven which allowed them to rule.

The Shang were overthrown by King Wu of Zhou in 1046 BCE who founded the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE). The Zhou would be the last before the Qin Dynasty (221-210 BCE) which unified China and gave it its name. By the time of the Zhou and Qin dynasties, Chinese culture was already formed, so if one discounts the Xia Dynasty as a politically motivated fabrication of later historians, one must conclude that the Shang Dynasty is responsible for the foundations of Chinese culture and civilization. If one accepts the Xia as historical reality, then it was still during the Shang Dynasty that the most important aspects of the culture were developed.

King Tang of Shang

Tang ruled the kingdom of Shang, a vassal state under the higher rule of the Xia Dynasty. His years of rule are disputed. Historian Joshua J. Mark notes how "The dates popularly assigned to him (1675-1646 BCE) do not in any way correspond to the known events in which he took part and must be considered erroneous." The last emperor of the Xia Dynasty, Jie, was a tyrant who lived for his own pleasure at the expense of his people. Tang endured this treatment as long as he could for the sake of harmony and peace and because, most of all, it was believed that the Xia ruled according to the mandate of heaven, the principle that the gods gave certain people the right to rule over others. Eventually, Tang came to see that the Xia had lost the mandate and led his people in revolt.

At the Battle of Mingtiao, fought in the midst of a huge rainstorm of thunder and lighting, Tang defeated Jie. Jie ran from the field and sought safety in exile, eventually dying from an illness. Tang abolished Jie's tyrannical policies and excessive taxes and instituted a new government, which worked for the people instead of against them.

Although Tang, and his successors, kept a standing army of around 1,000 troops at the ready, he lowered the number of conscripts and the amount of time one needed to serve. He also began government-funded social programs for the poor. One of these included giving specially marked gold coins to poor people who had needed to sell their children to survive a famine; the coin was issued so they could buy their children back. The country suffered from famine a number of times during Tang's reign but was on the whole very prosperous.

Stability & Economy

Historian Justin Wintle notes that "the presence [on both banks of the Yellow River] of vast quantities of loess - an exceptionally fertile alluvial sediment" and the Shang's prudent use of this soil, led to their ability to "grow significantly more food than they, or their dependents, required, thus releasing labor for such enterprises as the Shang tombs, the Great Wall of China, the Grand Canal and the early proliferation of cities" (6). One of the reasons the Xia dynasty's place in history is questioned by modern historians is that there is no way to really tell if the cities assigned to the Xia are not actually early Shang because the Shang Dynasty built so many.

The Shang initiated the technique of hangtu ('stamped-earth') in constructing these cities. Wintle explains that hangtu "involves compacting soil, usually with up-ended logs or beams, into a hard base which is then used as a platform upon which to erect wooden edifices, or built up using the same process to form walls and ramparts. Its appearance, especially in the north of China, denotes considerable manpower resources" (11). The use of hangtu, and the ornate tombs and public building projects of the Shang, all point to political stability and a thriving economy which allowed people the freedom from subsistence farming to participate in such projects. The best example of this can be seen in the city of Erligang in Zhengzhou.

Erligang

In 1952 the remains of a vast city from the Shang Dynasty were discovered near the modern city of Zhengzhou. This city had walls 32 feet (10 m) high and an amazing 65 feet (20 m) thick which ran for over four miles (7 km) to enclose an area of over one square mile (3 km²). Wintle notes that "nothing of comparable magnitude belonging to the same period has been detected elsewhere in east Asia and it is calculated that to build Erligang would have taken 12,000 men ten years" (16). The excavations also uncovered bronze foundries, which were used to craft weapons and statues. The weapons of the Shang military were all bronze and finds at excavations have shown that they were well armed. Still, the arts were as important to the Shang as military campaigns. The bronze statues found at Erligang are far superior in craftsmanship and size to those found anywhere else from the same time.

Besides work in bronze, the craftspeople of the Shang Dynasty were also experts in stonework, especially jade. Grave goods of very ornate jade workmanship have been found, including bodies covered in jade shingles, like armor plates. In textiles, the artists were equally skilled. Work in silk and other woven materials was of a very high quality which is clear from the clothing of carefully preserved bodies from Shang Dynasty tombs.

Bone workshops were also discovered at Erligang. Bone workshops in ancient China were industrial centers where artisans created objects from bone and stone for ceremonial or decorative purposes, and their presence at Erligang, along with the bronze foundries and artifacts, indicates enormous wealth. Throughout early Chinese history, artisans usually worked from rural homes to make their pieces in bone or stone; an industrial complex of the size at Erligang would have meant that the city could attract skilled craftsmen from other areas to live and work in the city.

Chinese Religion

The prosperity and stability of the Shang Dynasty not only produced a thriving economy and great works of art but also allowed for development of religious thought and ritual. Historian Joshua J. Mark writes:

Prior to the Shang, the people worshipped many gods with one supreme god, Shangti, as head of the pantheon. Shangti was considered 'the great ancestor' who presided over victory in war, agriculture, the weather, and good government. Because he was so remote and so busy, however, the people seem to have required more immediate intercessors for their needs and so the practice of ancestor worship began.

The Shang Dynasty not only developed ancestor worship but also the link between the people and the king and the king and the gods. This led to a completely harmonious understanding of life where the planes of the divine and the human, the rulers and the ruled, were intertwined. Religious thought cannot develop when one is concerned for one's safety or family, and so, this is further proof of the stability of the Shang Dynasty and of the validity of the later records claiming it was a time of great happiness and prosperity for the people.

Taoism is thought to have developed during this time and the folk religion (including ancestor worship) which grew out of Taoist teachings. These religious developments included a belief in an afterlife and allowed one to call on one's ancestors for help in one's life. It also meant that the king who ruled over the land was not ruling by chance or whim but by the will of the all-powerful gods and in harmony with one's ancestors. Joshua J. Mark comments on this:

When someone died, it was thought, they attained divine powers and could be called upon for assistance in times of need. This practice led to highly sophisticated rituals dedicated to appeasing the spirits of the ancestors which eventually included ornate burials in grand tombs filled with all one would need to enjoy a comfortable afterlife. The king, in addition to his secular duties, served as chief officiate and mediator between the living and the dead and his rule was considered ordained by divine law. Although the famous Mandate of Heaven was developed by the later Zhou Dynasty, the idea of linking a just ruler with divine will has its roots in the beliefs fostered by the Shang.

The Calendar, Writing & Music

The traditional Chinese calendar was lunar, based on the moon, but the farmers needed a solar calendar so they could tell when the best times were to plant and harvest their crops. During the Shang Dynasty a man named Wan-Nien measured time over a one-year period by measuring the shadows throughout a day using a sun-dial and a water clock. He established the two solstices of the year and, after that, the two equinoxes and so created the calendar known as the Wan-lien-li or the "perpetual calendar". Before Wan-Nien, the Chinese believed there were 354 days in a year, but Wan-Nien proved there are 365.

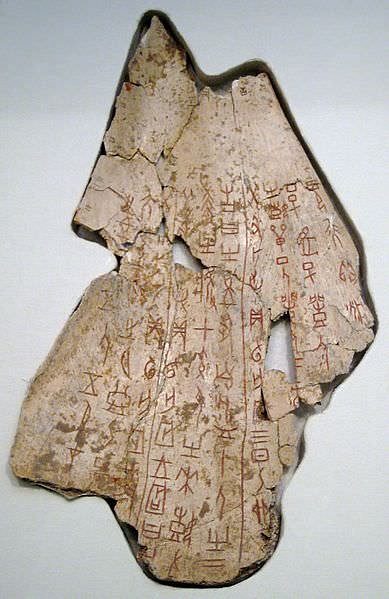

The exact date of Wan-Nien's work is unknown but when it comes to the invention of writing there is a little more certainty. Writing developed in China gradually through the use of oracle bones. Oracle bones were shells of turtles or bones of animals, which were used in divination. If a person wanted to know their future they would go to a fortune-teller who would carve a question on a bone or shell. If one wanted to know whether to attend a friend's wedding, the fortune teller would write "I will go to my friend's wedding" on one part of the shell and "I will not go to my friend's wedding" on another part. These were not necessarily words but could have been symbols, pictograms. The shell or bone would then be placed in a fire until it cracked. The fortune-teller would interpret that crack to answer the question.

This practice led to the development of writing as people had more complex questions for the oracle bones than whether to attend a wedding. By c. 1250 BCE writing had developed in recognizable form. As Wintle puts it, "the first unambiguous appearance of a Chinese script in the form of inscribed oracle bones" comes from the city of Anyang at this time (17). The script found on these bones is archaic but is definitely Chinese script and able to be read.

The invention of writing aided in the discipline of science as observations could be recorded more accurately. The Oracle Scripts are accounts of eclipses and other celestial events written by astronomers of the time. Their works also show advances in mathematics during the same period and the development of odd and even numbers and principles of accounting. The I-Ching (also known as The Book of Changes) was either written or compiled at this same time (c. 1250-1150 BCE). The I-Ching is a book of divination with roots going back to the fortune-tellers of the rural areas and their oracle bones.

Musical instruments were also developed by the Shang. At Yin Xu, near Anyang, excavations have revealed instruments from the Shang period such as the ocarina (a wind instrument), drums, and cymbals. Bells, chimes, and bone flutes have been discovered elsewhere. The founding of the city of Anyang, which would become the capital of the Shang Dynasty, corresponds to the height of its power.

Decline & Fall

The Shang Dynasty may have gone through a brief decline prior to the founding of Anyang, around 1300 BCE, when separate states under Shang rule seem to have broken away economically, if not politically. Archaeologists have come to this conclusion through a study of the trade at the time which indicates a rise in the economy of independent states but not, as before, of the whole region under Shang control. This claim is in doubt, however, as the physical evidence is not decisive.

The two greatest emperors after Tang were Pan Geng, who moved the capital to Yin (so that the dynasty is sometimes referred to as Yin Shang), and Wu Ding. Wu Ding is one of the only Shang emperors whose existence is corroborated by the physical evidence of archaeology. He reigned for 58 years from 1250-1192 BCE and during this time the country developed many of the most important advances listed above as well as those in medicine, dentistry, and the fine arts.

After Wu Ding's reign, the dynasty began to decline until the last emperor, Zhou (also known as Xin) who forgot his duty to his people and concentrated on gratifying his own desires. He spent most of his time with his concubine Daji and not only neglected his duties but made his people pay for his luxuries and idleness. He became a worse tyrant than Jie of the Xia Dynasty had been and was finally overthrown by King Wu, of the province of Zhou, at the Battle of Muye in 1046 BCE.

The Shang Dynasty was replaced by the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) which began to dissolve in its final years into the phase known as the Warring States Period (c.481-221 BCE). During this time, the seven states which had been under Zhou control fought each other for supreme rule of the country. The state of Qin (pronounced 'chin') was victorious and China takes its name today from the Qin Dynasty. Unlike the Shang or the Zhou, the Qin began badly and only became worse over time until they were overthrown by the Han. The Shang Dynasty, which was responsible for so many important advancements in culture, was looked back upon as a golden age of prosperity and, in many ways, it was.

![China - History From Neolithic Cultures through Great Qing Empire (10) by Tanner, Harold M [Paperback (2010)]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/31HbtYMRV3L._SL160_.jpg)