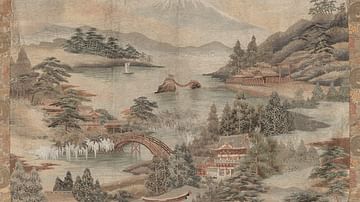

The Shimabara Rebellion was a peasant uprising that occurred from 17 December 1637 to 15 April 1638 in Japan's southern island of Kyushu. Economic desperation, famine, and religious persecution led the peasants of the Shimabara peninsular region to take up arms against the shogunate (military government), culminating in the siege of Hara Castle, where the rebellion was quashed and its leader, a 16-year-old boy, was slain.

Causes

The benevolence that was denied to the peasants of the Shimabara region during the lordship of Matsukura Shigemasa (1574-1630) and his son Katsuie (1598-1638) would not be forgotten by those who had been afflicted by the extreme consequences of their greed and wrath. Overtaxation, due to political grandstanding and the construction of Shimabara Castle, and famine had brought the locals to their knees. While other daimyo (lords) may have shown leniency during times of hardship, the Matsukura duo did not, with there being harsh penalties for those that could not meet their hefty obligations. Punishments included torture and even death, a fate that befell many, including Christians, who were persecuted because of an edict that had been passed in 1612 outlawing the religion. Of the latter, many were thrown into scalding onsen (hot springs) that boiled them alive. Interestingly, Shigemasa's own death came in a similar fashion when upon entering an onsen the sudden change in temperature caused an aneurism which he did not survive.

The peasants, many of whom were former samurai and veterans, were incensed by their treatment and plotted an insurrection in secret on Yushima (Yu Island, colloquially known today as 'Cat Island').

The exact catalyst for the rebellion is in question: some scholars believe it to be due to a local official who kidnapped and tortured the daughter of a farmer who could not pay his taxes, and others point to the magistrate who tore up a portrait that the peasants worshipped after it had miraculously mounted itself on a villager's wall. In both tales, the official is murdered soon after. Another possible beginning is that of the execution of two men, and their families, who had held religious ceremonies after purportedly seeing miracles being performed by a 16-year-old boy known as Amakusa Shiro.

Shiro, or Jerome as he was known after his baptismal ceremony, was seen as a messianic figure and a portent of the end times. The Tokugawa bakufu (military government) framed the boy as being a conniving trickster – a sorcerer who followed a pagan cult. Although some scholars believe him to have been a mere puppet of the rebel ringleaders, he was nonetheless an inspirational figurehead. In the early days of the rebellion, his was a rallying cry to those acolytes of Christianity who were rampaging across Shimabara, Karatsu, and the Amakusa Islands. They terrorised villagers, accepting those that willingly joined them on their crusade and dragging along any that did not, and ransacked temples and shrines even going so far as to decapitate the Jizō stone statues that litter the compounds, a sight that can be seen to this day.

Rebellion

Advancing upon the town of Shimabara, a large rebel force soon amassed at the gates of Shimabara Castle, where, after an initial sally out by the castle defenders had gone awry, the Matsukura samurai forces were forced to shut themselves inside the fortress' walls and await aid. Matsukura Katsuie himself was fortunate enough to have been visiting Edo (modern Tokyo) during the rebellion. The rebels settled in, readying themselves for a protracted siege, before receiving news that Shiro wished for them to bolster the ranks of those rebels in the Amakusa Islands. By that stage, the insurrectionist army that had gathered outside the castle's walls numbered some 8,000, and thus many of them siphoned off and took to their vessels, rushing to the aid of their comrades. A token number of rebels remained to continue the siege.

A governor of the Amakusa Islands, Miyake Tobee, amassed allied forces and set out to face the small band of rebels, his expectation being that there were at most a few hundred insurrectionists. On 29 December, upon engaging the peasants in the Battle of Hondo Castle, Miyake's flank was threatened by rebels from the mainland, and they were ultimately forced to flee towards the safety of Tomioka Castle, with Miyake himself being killed in combat. Although the rebels, after the battle, would have felt confident of their abilities, they were not so of Hondo Castle, which was merely a fort on a hill and could not be properly defended. They moved on to assault Tomioka Castle, but after only a few days of besieging the castle (January 2-6) and not making any substantial efforts towards capturing the fortress, the rebels received news that a massive shogunate army was en route to Shimabara to put down the revolt. Realising the urgency of their situation and the need to secure a defensible position, Shiro commanded that the rebel army should return to their boats and sail for a citadel complex that had been plundered for its resources and long abandoned: the mutilated remains of Hara Castle.

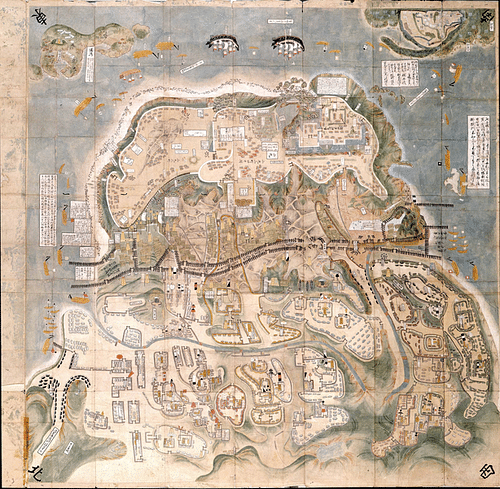

The Siege of Hara Castle

Dismantling their ships, the rebels used the scavenged lumber and other resources to shore up the castle's defensible positions, all the while knowing that the shogunate's army was growing ever closer. Numbering over 100,000 men, the army outnumbered the rebels almost 3 to 1. Its leader Itakura Shigemasa (1588-1638) was intent on rooting out the rebels in quick order, however, his initial probing attacks were met by fierce resistance.

In an attempt to bypass the walls, the besiegers tunnelled underneath them. Their plans were for nought, however, when rebels heard them digging under the earth. Flooding the tunnels with smoke and waste, the attackers were forced to employ other tactics, such as building artillery towers from which to shoot down on the defenders, a ploy that was met with similar failure.

The Protestant Dutch in Nagasaki were called upon to aid the bakufu's campaign, a request that they fulfilled by sending cannons and shot. As the siege continued, increasing pressure was put on them to provide further, more direct assistance. They agreed to send a ship, De Ryp, to lie off the coast of Hara Castle and rain down cannonades upon the defenders. Almost entirely unsuccessful, much of what they fired overshot the rebels and landed in the besiegers' camp. By moving some of the cannons from the ship to land, they created more stable positions from which to fire, however, after a Dutchman was killed involving a mishap with a cannon, they were sent home. During their involvement, the rebels sent an arrow into Shigemasa's camp with a note that mockingly read:

Are there no longer courageous soldiers in the realm to do combat with us, and weren't they ashamed to have called in the assistance of foreigners against our small contingent? (Doeff, 26)

Itakura Shigemasa was eventually killed in an assault on the castle and was replaced by Matsudaira Nobutsuna (1596-1662), who continued to assault and batter the castle's walls. Eventually, as supplies dwindled, the rebels became desperate. On 12 April, the rebels mustered what forces they could and crept out the castle gates, approaching the enemy's camp under the cover of darkness. However, a watchman spotted the lights of their lit matchlocks and alerted nearby troops. Before long, the rebel's small warband was destroyed. Matsudaira had the bellies of those rebels killed cut open and found that many of them had been scavenging what they could to eat, clearly signalling that their food stores were low. This information was backed up by the interrogations of captured rebels and the words of Yamada Emosaku, a traitor amongst the rebels' ranks. It was at this time that an assault on the fortress was ordered, with Matsudaira figuring that the rebels would be weak from food insufficiencies. This time, the rebels could not hold back the inevitable.

Throwing cooking pots and cauldrons down from the ramparts, the rebels weaponised what they could in their desperate attempt to drive off the attackers, but it was not enough, and shogunate soldiers stormed over the walls and into the compound. A mass slaughter ensued over the next 3 days in which very few were left alive. While a handful of rebels did escape, many were hunted down by patrols that combed the countryside for days after the final assault. Shiro Amakusa was eventually rooted out and killed; his decapitated head was displayed on the end of a spear in Nagasaki as a warning to others.

Aftermath

That the Shimabara Rebellion has been attributed to Christianity was in no small part due to the machinations of Tokugawa's court. The shogunate was quick to label the instigators of the rebellion as doomsday cultists to delegitimise and garner public support against them. The accusations eased the public's concerns that similar revolts could break out across the country, for only Kyushu had a large enough population of Christians to warrant such a claim. With the supposed meddling of the Portuguese Jesuit priests, a rebellion, the bakufu reasoned, was an inevitability.

Not long after the dust had settled at Hara Castle did the shogunate move to expel all foreigners from Japan's shores, save for the Dutch who were relegated to a compound in Nagasaki. The Portuguese quickly responded by sending a vessel to Japan, so that they might reestablish their relationship, however, most of the crew were executed and those that were spared were sent fleeing back to Europe with a warning to never return. It would take over 200 years for Japan to finally open its doors to the world again when American Matthew Perry arrived on their shores in the mid-1800s.

The end of the rebellion was the beginning for those known as Kakure Kirishitans, or hidden Christians. Made known in our modern world through the writings of Shūsaku Endō in his novel Silence, hidden Christians kept their faith secret in a world that had become intensely aggressive towards their beliefs. While many apostatised when found out, many others chose to die as a martyr. The rituals of the hidden Christians are still carried out today by those few practitioners who remain.

Conclusion

Born from desperation, whether religious or not, the Shimabara Rebellion has had an indelible effect on the land. The leadership of an exceptional young man led to tens of thousands of peasants rising up against their oppressors and eventually dying en masse. So many died that the bakufu was compelled to repopulate the countryside with peasants from across Japan, and all were forced to align themselves with local Buddhist shrines. Today, one may notice that there are many differing dialects, and localised cultural practices present in the Shimabara peninsula because of these migrations. Finally accepted in Japan, Amakusa Shiro can rest easy knowing that his faith is now undenied and that peace reigns over the once-troubled land.