The great temples and monuments of ancient Egypt continue to fascinate and amaze people in the modern day. The sheer size and scope of structures like the Great Pyramid at Giza or the Temple of Amun at Karnak or the Colossi of Memnon are literally awe-inspiring and naturally encourage questions regarding how they were built. All across the Egyptian landscape rise immense structures, thousands of years old, which have given rise to many different theories as to their construction. While a number of very significant questions remain unanswered, the simplest explanation for many can be found in ancient Egyptian inscriptions, texts, wall paintings, tomb inscriptions, art, and artifacts: the ancient Egyptians had an extraordinary command of science and technology.

Ancient monuments and grand temples aside, the ancient Egyptians invented a number of items which one simply takes for granted in the modern day. Paper and ink, cosmetics, the toothbrush and toothpaste, even the ancestor of the modern breath mint, were all invented by the Egyptians. Additionally, they made advances in almost every sphere of knowledge from the manufacture of simple household goods to beer brewing, engineering and construction, to agriculture and architecture, medicine, astronomy, art and literature. Although they did not have command of the wheel until the arrival of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE), their technological skills are evident as early as the Predynastic Period (c. 6000-c. 3150 BCE) in the construction of mastaba tombs, artworks, and tools. As the civilization advanced, so did their knowledge and skill until, by the time of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE), the last to rule Egypt before it was annexed by Rome, they had created one of the most impressive cultures of the ancient world.

Household Goods

The simple handheld mirror one finds so commonplace in the present day was created by the Egyptians. These were often decorated with inscriptions and figures, such as that of the protector-god Bes, and were owned by men and women alike. More ornate wall mirrors were also a part of middle- and upper-class homes and were likewise decorated. The ancient Egyptians were very aware of their self-image and personal hygiene and appearance was an important value.

Toothbrushes and toothpaste were invented because of the grit and sand which found its way into the bread and vegetables of the daily meals. The image presented in the modern day by art and movies of Egyptians with exceptionally white teeth is misleading; dental problems were common in ancient Egypt, and few, if any, had an all-white smile. Dentistry developed to deal with these difficulties but never seems to have advanced at the same rate as other areas of medicine. While it appears doctors were fairly successful in their techniques, dentists were less so. To cite only one example, the queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) actually died from an abscess following a tooth extraction.

Toothpaste was made of rock salt, mint, dried iris petals, and pepper, according to one recipe from the 4th century CE, which dentists in 2003 CE tried and found to be quite effective (although it made their gums bleed). Another earlier recipe suggested ground-up ox hooves and ash, which, mixed with one's saliva, created a cleansing paste for the teeth. This recipe, lacking the mint, did nothing for one's breath and so tablets were created from spices like cinnamon and frankincense heated in a honey mixture, which became the world's first breath mints.

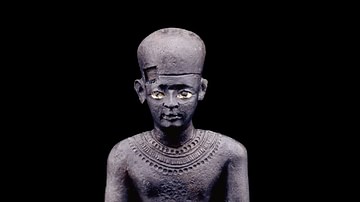

Ornamentation on furniture, although first appearing in Mesopotamia, became more elaborate in Egypt and more refined as time went on. Different colors of ink and different weights of paper were also developed by the Egyptians through their invention of paint cakes and processing of the papyrus plant. Small area rugs one finds in homes all over the world also were either invented or advanced in Egypt (made of the same papyrus plant) as were knick-knacks in the form of cats, dogs, people, and the gods. Small statues of gods such as Isis, Bes, Horus, Hathor, among others have been found as parts of household shrines as the people worshiped their gods in the home more often than at temple festivals. These statues were made of material ranging from sun-dried mud to gold depending on one's personal wealth.

Engineering & Construction

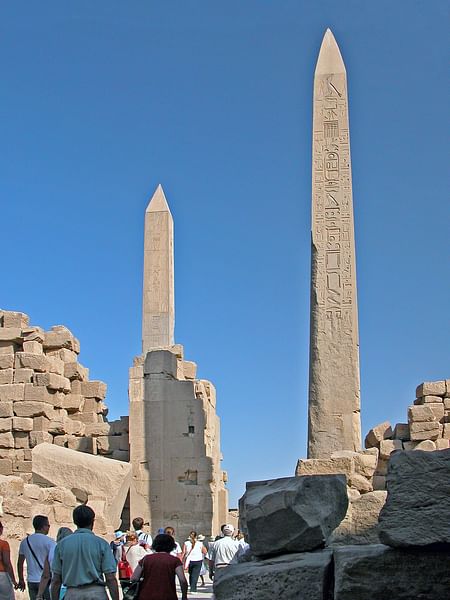

The great temples of ancient Egypt arose from the same technological skill one sees on the small scale of household goods. The central value observed in creating any of these goods or structures was a careful attention to detail. The Egyptians are noted in many aspects of their culture as a very conservative society, and this adherence to a certain way of accomplishing tasks can clearly be seen in their construction of the pyramids and other monuments. The creation of an obelisk, for example, seems to have always involved the exact same procedure performed in precisely the same way. The quarrying and transport of obelisks are well documented (though how the immense monuments were raised is not) and shows a strict adherence to a standard procedure.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser was successfully built according to the precepts of the vizier Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE), and when his plans were deviated from by Sneferu during of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613- c. 2181 BCE), the result was the so-called 'collapsed pyramid' at Meidum. Sneferu returned to Imhotep's original engineering plans for his next projects and was able to create his Bent Pyramid and Red Pyramid at Dashur, advancing the art of pyramid building which is epitomized in the Great Pyramid at Giza.

The technological skill required to build the Great Pyramid still mystifies scholars in the present day. Egyptologists Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs comment on this:

Because of their immense size, building pyramids posed special problems of both organization and engineering. Constructing the Great Pyramid of the pharaoh Khufu, for example, required that more than two million blocks weighing from two to more than sixty tons be formed into a structure covering two football fields and rising in a perfect pyramidal shape 480 feet into the sky. Its construction involved vast numbers of workers which, in turn, presented complex logistical problems concerning food, shelter, and organization. Millions of heavy stone blocks needed not only to be quarried and raised to great heights but also set together with precision in order to create the desired shape. (217)

In order to accomplish this, the vizier would delegate responsibility to subordinates who would further delegate tasks to others. The bureaucracy of the Old Kingdom of Egypt set the paradigm for the rest of the country's history in accounting for every aspect of a building project and making sure each step was proceeding according to plan. Later in the Old Kingdom, Weni, known as the Governor of the South, would leave an inscription detailing how he traveled to Elephantine for granite for a false door for a pyramid and dug five canals for towboats to bring supplies for further construction (Lewis, 33). Records such as Weni's show the immense amount of effort required in building the monuments one finds in Egypt today. There are numerous inscriptions relating to supplies and difficulties in building the pyramids at Giza but no definitive explanation of the practical means by which they were built.

The most popular theory involves ramps which were constructed as the pyramid was raised but this is actually untenable as Brier and Hobbs note:

The problem is one of physics. The steeper the angle of an incline, the more effort necessary to move an object up that incline. So, in order for a relatively small number of men, say ten or so, to drag a two-ton load up a ramp, its angle could not be more than about eight percent. Geometry tells us that to reach a height of 480 feet, an inclined plane rising at eight percent would have to start almost one mile from its finish. It has been calculated that building a mile-long ramp that rose as high as the Great Pyramid would require as much material as that needed for the pyramid itself - workers would have had to build the equivilent of two pyramids in the twenty-year time frame. (221)

A modification of the ramp theory was proposed by the French architect Jean-Pierre Houdin who claims ramps were used but on the inside of the pyramid, not the exterior. Ramps may have been used externally in the initial stages of construction but then were moved inside. The quarried stones were then brought in through the entrance and moved up the ramps to their position. This, Houdin claims, would account for the shafts one finds inside the pyramid. This theory, however, does not account for the weight of the stones or the number of workers on the ramp required to move them up an angle inside the pyramid.

A much more cogent theory has been proposed by engineer Robert Carson who suggests that water power was used. It has been clearly substantiated that the water tables of the Giza plateau are quite high and were more so during the period of the Great Pyramid's construction. Water could have been harnessed and pressure exerted via a pump, as Carson claims, to help raise the stones up a ramp to their intended position. Egyptologists still debate the purpose of the shafts inside the Great Pyramid with some claiming they served a spiritual purpose (so the king's soul could ascend to the heavens) and others a practical left over from construction. Egyptologist Miroslav Verner states that these questions cannot finally be answered as we have no definitive texts or archaeological evidence to point in one direction or another.

While that may be so, Carson's claim for water power in construction makes more sense than many others (such as a hoist being used to transport the stones when, clearly, there is no evidence whatsoever for Egyptian use or knowledge of a crane) and it is known that the Egyptians were acquainted with the concept of the pump. King Senusret (c. 1971-1926 BCE) of the Middle Kingdom drained the lake at the center of the Fayyum district during his reign through the use of canals and pumps were used to divert resources from the Nile in other periods. Ukranian engineer Mikhail Volgin also cites water as central to the Great Pyramid's construction and claims that the pyramids were not designed as tombs at all actually but were immense waterworks depots. He points to the lack of any mummies found in the pyramids, their shape, and the high water table of the Giza plateau as evidence for his claim.

Agriculture & Architecture

Whatever one makes of Volgin's water theory concerning the pyramids, Egyptian society did depend on a reliable supply of clean water for their crops and livestock. Ancient Egypt was an agricultural society and so naturally developed innovations to help cultivate the land. Among the many inventions or innovations of the ancient Egyptians was the ox-drawn plow and improvements in irrigation. The ox-drawn plow was designed in two gauges: heavy and light. The heavy plow went first and cut the furrows while the lighter plow came behind turning up the earth. Once the field was plowed then workers with hoes broke up the clumps of soil and sowed the rows with seed. To press the seed into the furrows, livestock was driven across the field and the furrows were closed. All of this work would have been for nothing, however, if the seeds were denied sufficient water and so regular irrigation of the land was extremely important.

Egyptian irrigation techniques were so effective they were implemented by the cultures of Greece and Rome. It has been noted that the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus (c. 585 BCE) studied in Egypt and may have brought these innovations back to Greece (although he also studied at Babylon and could have learned irrigation techniques there). New irrigation techniques were introduced during the Second Intermediate Period by the people known as the Hyksos, who settled in Avaris in Lower Egypt, and the Egyptians improved upon them; notably through the expanded use of the canal. The yearly inundation of the Nile overflowing its banks and depositing rich soil throughout the valley was essential to Egyptian life but irrigation canals were necessary to carry water to outlying farms and villages as well as to maintain even saturation of crops near the river. Historian Margaret Bunson writes:

Early farmers dug trenches from the Nile shore to the farmlands, using draw wells and then the Shaduf, a primitive machine that allowed them to raise levels of water from the Nile into canals...Fields thus irrigated produced abundant annual crops. From the predynastic times agriculture was the mainstay of the Egyptian economy. Most Egyptians were employed in agricultural labors, either on their own lands or on the estates of the temples or nobles. Control of irrigation became a major concern and provincial officials were held responsible for the regulation of water. (4)

Architecture surrounding these canals was sometimes quite ornate as in the case of the pharaoh Ramesses the Great (1279-1213 BCE) and his city of Per-Ramesses in Lower Egypt. Ramesses the Great was one of the most prolific builders in Egyptian history; so much so that there is no ancient site in Egypt which does not make some mention of his reign and accomplishments. In creating his grand monuments, Ramesses' engineers called upon another invention of the Old Kingdom: the corbelled arch. Without the concept of the corbelled arch, architecture the world over would be significantly diminished and some structures, such as the Great Pyramid, would be impossibilities. The grand halls of the temples of Egypt, the inner sanctums, the temples themselves would all have been likewise impossible if not for this advance in engineering and construction.

Mathematics & Astronomy

Astronomy was important to the ancient Egyptians on two levels: the spiritual and the practical. Egypt was thought to be a perfect reflection of the land of the gods and the afterlife a mirror image of one's life on earth. This duality is apparent in Egyptian culture in every aspect and epitomized in the obelisk which was always raised in pairs and believed to reflect a divine pair appearing at the same time in the heavens. The stars told the stories of the gods' accomplishments and trials but also indicated the passage of time and the seasons. Egyptologist Rosalie David comments on this:

The Egyptians were noted astronomers who distinguised between the "imperishable stars" (the circumpolar stars) and the "indefatigable stars" (the planets and stars not visible at all hours of the night). They used stellar observations to determine the true north and were able to orientate the pyramids with great accuracy...Each temple was possibly aligned toward a star that had a particular association with the deity resident in that building. (218)

On a more practical level, the stars could tell one when it was going to rain, when it was nearing time to plant or harvest crops, and even the best times for making important decisions such as building a home or temple or starting a business venture. Astronomical observations led to astrological interpretations which may have been adopted from Mesopotamian sources via trade. Strictly astronomical examination of the night skies, however, were interpreted in terms of pragmatism and recorded in mathematical calculations measuring weeks, months, and years. Although the calendar was invented by the ancient Sumerians, the concept was adapted and improved upon by the Egyptians.

According to many Egyptologists, mathematics in Egypt was entirely practical. Rosalie David, for example, claims, "Mathematics served basically utilitarian purposes in Egypt and does not seem to have been regarded as a theoretical science" (217). Ancient writers such as Herodotus and Pliny, however, consistently mention the Egyptians as the source of theoretical mathematics, and they are not the sole sources on this. Many ancient writers, Diogenes Laertius and his sources among them, point to philosophers such as Pythagoras and Plato, who both studied in Egypt, and the importance of mathematical knowledge in their belief systems. Plato regarded the study of geometry necessary for clarity of mind and it is thought he took this concept from Pythagoras who first learned it from the priests in Egypt. In his book Stolen Legacy: The Egyptian Origins of Western Philosophy, scholar George G.M. James argues western philosophical concepts are falsely attributed to the Greeks who merely developed Egyptian ideas, and this same paradigm may hold for the study of mathematics as well.

There is no doubt that the Egyptians used mathematics on a daily basis for far more mundane purposes than the pursuit of ultimate truths. Mathematics was used in record keeping, in developing the schematics for machines such as the water pump, in calculating tax rates, and in drawing up designs and siting locations for building projects. Mathematics was also used on a very simple level in the medical arts in writing prescriptions for patients and mixing the ingredients for medicines.

Medicine & Dentistry

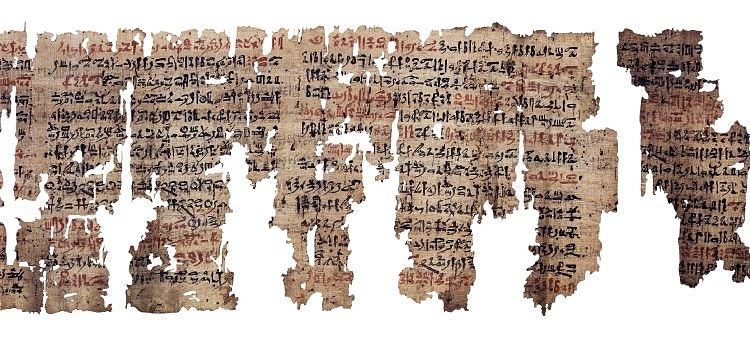

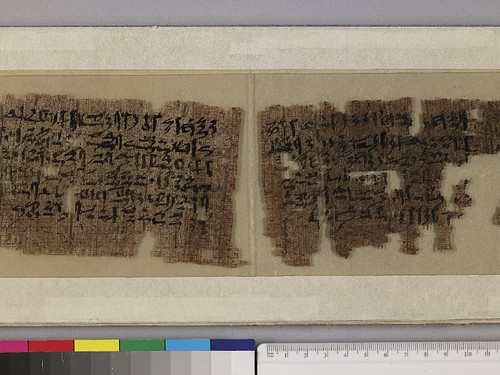

Medicine in ancient Egypt was intimately tied to magic. The three best-known works dealing with medical issues are the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE), the Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE), and the London Medical Papyrus (c. 1629 BCE) all of which, to one degree or another, prescribe the use of spells in treating diseases while at the same time exhibiting a significant degree of medical knowledge.

The Ebers Papyrus is a text of 110 pages treating ailments such as trauma, cancer, heart disease, depression, dermatology, gastrointestinal distress, and many others. The Edwin Smith Papyrus is the oldest known work on surgical techniques and is thought to have been written for triage surgeons in field hospitals. This work shows detailed knowledge of anatomy and physiology. The London Medical Papyrus combines practical medical skill with magical spells for the treatment of conditions ranging from eye problems to miscarriages.

Medical texts, other than these, also give prescriptions for dental problems. Herodotus notes that doctors in Egypt were all specialists in their particular field and this applied to dentists as well as any other. There was a position known as "One Who is Concerned with Teeth", regarded as a dentist and another known as "One Who Deals with Teeth" who may have been a kind of pharmacist. The dentist was often called upon to pull a tooth but it seems that oral surgery was seldom performed. Most of the medical texts dealing with dental issues are preventative or related to pain management.

Based on the evidence of mummies who have been examined, as well as letters and other documents, ancient Egyptians seem to have experienced fairly severe and widespread dental problems. Dentistry does not seem to have evolved at the same pace as other branches of medicine but still was more advanced and showed a greater knowledge of dealing with oral pain than later remedies practiced by other cultures. The first known dental procedure dates to 14,000 years ago in Italy, according to evidence published in 2015 CE, but the first dentist in the world known by name was the Egyptian Hesyre (c. 2660 BCE) who held the position of Chief of Dentists and Physician to the King during the reign of Djoser (c. 2670 BCE) showing that dentistry was considered an important practice as early as Djoser's reign and probably earlier. This being so, it is unclear why dental practices did not evolve to the same degree as other medical fields.

Artwork and many medical texts seem to largely ignore dental problems and toothaches, but non-medical texts address them as most likely caused by a tooth-worm which needed to be driven away by magical spells, extraction, and applying an ointment. This belief most likely came from Mesopotamia, specifically Sumer, as an ancient text from that region predates the Egyptian concept of the tooth-worm. Medical tools have been found which could have been used by dentists, but as none are labeled or referred to clearly in texts, one cannot say for certain. It is clear, however, that dentists had the ability to diagnose oral disease and the technology to operate on gums and teeth.

Art & Literature

Technology also influenced Egyptian art and literature, not only in how it was produced but in content and form. Obviously, the invention of papyrus and ink greatly facilitated writing and advances in copper tools replacing flint in carving improved quality of art; but the world the Egyptians created through their understanding of scientific measurements and technological advancements became both the subject and the canvas artists worked on.

The Poem of Pentaur, for example, which narrates the victory of Ramesses the Great over the Hittites at Kadesh, is not simply written on a sheet of papyrus or a plaque but proclaimed from the sides of temples in Abydos, Karnak, Abu Simbel, and his Ramesseum. The form the artist worked in, the stone of the temple, informs the content of the piece itself: Ramesses' great victory against overwhelming odds. The story is more impressive for the medium in which it is told.

This same is true for the stelae, obelisks, and other monuments throughout Egypt. The literature which is inscribed on these stone pieces gives them their own life while imbuing the story itself with greater meaning as both literary and visual art. In written texts, of course, technological advances appear constantly in stories whether The Tale of Sinuhe where the narrator speaks of his travels in other lands and what he finds lacking there or the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor where the technology of shipbuilding makes the story possible.

The ancient Egyptians believed that balance, harmony, in all aspects of life was most important and this value can be seen in almost all of their advances in the sciences and technology: what was found lacking in life was balanced by what was created by individual ingenuity. Although the gods were thought to have provided all good things to human beings, it was still an individual's responsibility to care for one's self and the greater community. Through their inventions and advances in knowledge, the Egyptians would have believed they were doing the god's will in making even better the grand life and world they had been given.