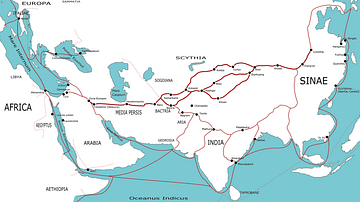

The Silk Road was a network of ancient trade routes, formally established during the Han Dynasty of China in 130 BCE, which linked the regions of the ancient world in commerce between 130 BCE-1453 CE. The Silk Road was not a single route from east to west and so historians favor the name 'Silk Routes', though 'Silk Road' is commonly used.

The European explorer Marco Polo (l.1254-1324 CE) traveled on these routes and described them in depth in his famous work but he is not credited with naming them. Both terms for this network of roads - Silk Road and Silk Routes - were coined by the German geographer and traveler, Ferdinand von Richthofen, in 1877 CE, who designated them 'Seidenstrasse' (silk road) or 'Seidenstrassen' (silk routes). Polo, and later von Richthofen, make mention of the goods which were transported back and forth on the Silk Road.

From West to East these goods included:

- Horses

- Saddles and Riding Tack

- The grapevine and grapes

- Dogs and other animals both exotic and domestic

- Animal furs and skins

- Honey

- Fruits

- Glassware

- Woolen blankets, rugs, carpets

- Textiles (such as curtains)

- Gold and Silver

- Camels

- Slaves

- Weapons and armor

From East to West the goods included:

- Silk

- Tea

- Dyes

- Precious Stones

- China (plates, bowls, cups, vases)

- Porcelain

- Spices (such as cinnamon and ginger)

- Bronze and gold artifacts

- Medicine

- Perfumes

- Ivory

- Rice

- Paper

- Gunpowder

The network was used regularly from 130 BCE, when the Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE) officially opened trade with the west, to 1453 CE, when the Ottoman Empire boycotted trade with the west and closed the routes. By this time, Europeans had become used to the goods from the east and, when the Silk Road closed, merchants needed to find new trade routes to meet the demand for these goods.

The closure of the Silk Road initiated the Age of Discovery (also known as the Age of Exploration, 1453-1660 CE) which would be defined by European explorers taking to the sea and charting new water routes to replace over-land trade. The Age of Discovery would impact cultures around the world as European ships claimed some lands in the name of their god and country and influenced others by introducing western culture and religion and, at the same time, these other nations influenced European cultural traditions. The Silk Road - from its opening to its closure - had so great an impact on the development of world civilization that it is difficult to imagine the modern world without it.

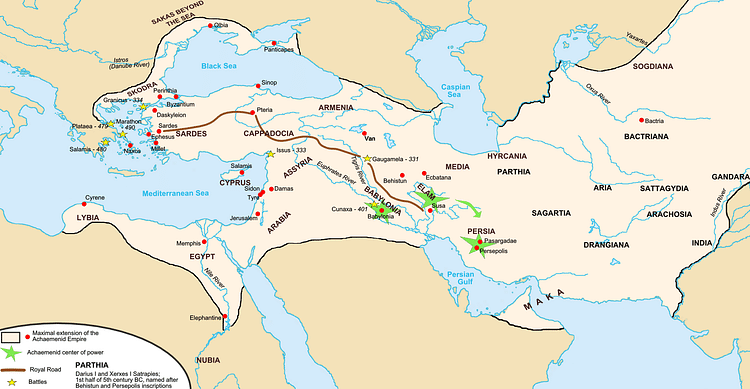

Persian Royal Road

The history of the Silk Road pre-dates the Han Dynasty in practice, however, as the Persian Royal Road, which would come to serve as one of the main arteries of the Silk Road, was established during the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE). The Persian Royal Road ran from Susa, in north Persia (modern day Iran) to the Mediterranean Sea in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) and featured postal stations along the route with fresh horses for envoys to quickly deliver messages throughout the empire. Herodotus, writing of the speed and efficiency of the Persian messengers, stated that:

There is nothing in the world that travels faster than these Persian couriers. Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor darkness of night prevents these couriers from completing their designated stages with utmost speed. (Histories VIII.98)

These lines would, centuries later, form the creed of the United States of America's post office. The Persians maintained the Royal Road carefully and, in time, expanded it through smaller side roads. These paths eventually crossed down into the Indian subcontinent, across Mesopotamia, and over into Egypt.

China & the West

After Alexander the Great conquered the Persians, he established the city (later the Greek Kingdom) of Alexandria Eschate in 339 BCE in the Fergana Valley of Neb (modern Tajikistan). Leaving behind his wounded veterans in the city, Alexander moved on. In time, these Macedonian warriors intermarried with the indigenous populace creating the Greco-Bactrian culture which flourished under the Seleucid Empire following Alexander's death.

Under the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I (r. 260-195 BCE) the Greco-Bactrians had extended their holdings. According to the Greek historian Strabo (63-24 CE) the Greeks “extended their empire as far as the Seres” (Geography XI.ii.i). `Seres' was the name by which the Greeks and Romans knew China, meaning `the land where silk came from' in East Asia. It is thought, then, that the first contact between China and the west came around the year 200 BCE.

The Han Dynasty of China was regularly harassed by the nomadic tribes of the Xiongnu on their northern and western borders. In 138 BCE, Emperor Wu sent his emissary Zhang Qian to the west to negotiate with the Yuezhi people for help in defeating the Xiongnu.

Zhang Qian's expedition led him into contact with many different cultures and civilizations in central Asia and, among them, those whom he designated the `Dayuan', the `Great Ionians', who were the Greco-Bactrians descended from Alexander the Great's army. The Dayuan had mighty horses, Zhang Qian reported back to Wu, and these could be employed effectively against the marauding Xiongnu.

The consequences of Zhang Qian's journey was not only further contact between China and the west but an organized and efficient horse breeding program throughout the land in order to equip a cavalry. The horse had long been known in China and had been used in warfare for cavalry and chariots as early as the Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE) but the Chinese admired the western horse for its size and speed. With the western horse of the Dayuan, the Han Dynasty defeated the Xiongnu. This success inspired Emperor Wu to speculate on what else might be gained through trade with the west and the Silk Road was opened in 130 BCE.

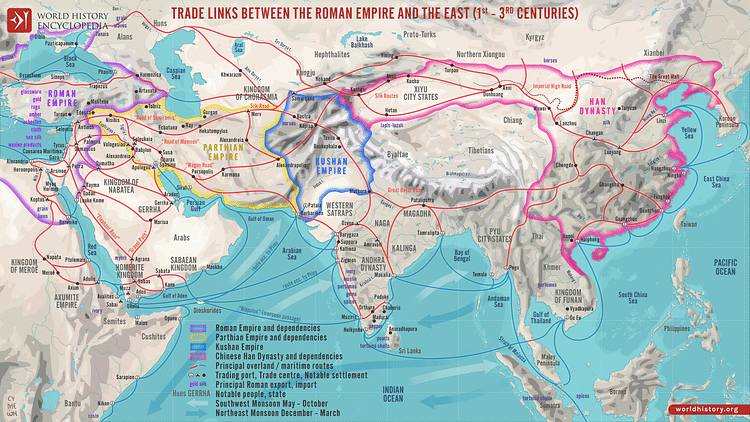

Between 171-138 BCE, Mithridates I of Parthia campaigned to expand and consolidate his kingdom in Mesopotamia. The Seleucid King Antiochus VII Sidetes (r. 138-129 BCE) opposed this expansion and, also wishing revenge for the death of his brother, Demetrius, waged war against the Parthian forces of Phrates II, Mithridates successor. With the defeat of Antiochus, Mesopotamia came under Parthian rule and, with it, came control of the Silk Road. The Parthians then became the central intermediaries between China and the west.

Goods Traded via the Silk Road

While many different kinds of merchandise traveled along the network of trade of the Silk Road, the name comes from the popularity of Chinese silk with the west, especially with Rome. The Silk Road routes stretched from China through India, Asia Minor, up throughout Mesopotamia, to Egypt, the African continent, Greece, Rome, and Britain.

The northern Mesopotamian region (present-day Iran) became China's closest partner in trade, as part of the Parthian Empire, initiating important cultural exchanges. Paper, which had been invented by the Chinese during the Han Dynasty, and gunpowder, also a Chinese invention, had a much greater impact on culture than did silk. The rich spices of the east, also, contributed more than the fashion which grew up from the silk industry. Even so, by the time of the Roman Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE – 14 CE) trade between China and the west was firmly established and silk was the most sought-after commodity in Egypt, Greece, and, especially, in Rome.

The Roman Love of Silk

Prior to becoming Emperor Augustus, Octavian Caesar seized on the controversial topic of silk clothing to denounce his adversaries Mark Antony (l. 83-30 BCE) and Cleopatra VII (l. 69-30 BCE) as immoral. As they both favored Chinese silk, which was increasingly becoming associated with licentiousness, Octavian exploited the link to deprecate his enemies. Octavian would triumph over Antony and Cleopatra; he could do nothing, however, to curtail the popularity of silk.

The historian Will Durant writes:

The Romans thought [silk] a vegetable product combed from trees and valued it at its weight in gold. Much of this silk came to the island of Kos, where it was woven into dresses for the ladies of Rome and other cities; in A.D. 91 the relatively poor state of Messenia had to forbid its women to wear transparent silk dresses at religious initiations. (329)

By the time of Seneca the Younger (l. 4 BCE – 65 CE), conservative Romans were more ardent than Augustus in decrying the Chinese silk as immoral dress for women and effeminate attire for men. These criticisms did nothing to stop the silk trade with Rome, however, and the island of Kos became wealthy and luxurious through their manufacture of silk clothing.

As Durant writes, "Italy enjoyed an 'unfavorable' balance of trade – cheerfully [buying] more than she sold” but still exported rich goods to China such as “carpets, jewels, amber, metals, dyes, drugs, and glass” (328-329). Up through the time of the emperor Marcus Aurelius (r.161-180 CE), silk was the most valued commodity in Rome and no amount of conservative criticism seemed to be able to slow the trade or stop the fashion.

Even after Aurelius, silk remained popular, though increasingly expensive, until the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 CE. Rome was survived by its eastern half which came to be known as the Byzantine Empire and which carried on the Roman infatuation with silk. Around 60 CE the west had become aware that silk was not grown on the trees in China but was actually spun by silkworms. The Chinese had very purposefully kept the origin of silk a secret and, once it was out, carefully guarded their silkworms and their process of harvesting the silk.

The Byzantine emperor Justinian (r. 527- 565 CE), tired of paying the exorbitant prices the Chinese demanded for silk, sent two emissaries, disguised as monks, to China to steal silkworms and smuggle them back to the west. The plan was successful and initiated the Byzantine silk industry. When the Byzantine Empire fell to the Turks in 1453 CE, the Ottoman Empire closed the ancient routes of the Silk Road and cut all ties with the west.

The Silk Road Legacy

The greatest value of the Silk Road was the exchange of culture. Art, religion, philosophy, technology, language, science, architecture, and every other element of civilization was exchanged along these routes, carried with the commercial goods the merchants traded from country to country. Along this network disease traveled also, as evidenced in the spread of the bubonic plague of 542 CE which is thought to have arrived in Constantinople by way of the Silk Road and which decimated the Byzantine Empire.

The closing of the Silk Road forced merchants to take to the sea to ply their trade, thus initiating the Age of Discovery which led to world-wide interaction and the beginnings of a global community. In its time, the Silk Road served to broaden people's understanding of the world they lived in; its closure would propel Europeans across the ocean to explore, and eventually conquer, the so-called New World of the Americas initiating the so-called Columbian Exchange by which goods and values were passed between those of the Old World and those of the New, universally to the detriment of the indigengous people of the New World. In this way, the Silk Road can be said to have established the groundwork for the development of the modern world.