The Spanish Requirement or Requerimiento was a document intended to be read out to and agreed upon by indigenous peoples during the Spanish conquest of the Americas. Created in 1513, the document outlined the history of Christianity, the superiority of the pope, and the obligation from this day onwards for all indigenous peoples to submit themselves to Spanish royal authority.

Ignoring the fact that the text of the Requerimiento was usually incomprehensible to its intended audience, the document was really a way for the Spanish to ease the guilt of their imperialism. Although legally obliged to declare the contents of the Requerimiento, in practice most conquistadors simply had someone – a friar, for example – skim through the most pertinent elements of the document and shout it across the battlefield as the cannons were being loaded to be fired. Despite the absurdity of the document and its delivery, the Requerimiento illustrates that even in this relatively early stage of European global imperialism, rulers were not entirely confident they had every right to trample over people in another part of the world, Christian or otherwise. If anything, the Requerimiento was written for the benefit of the Spanish rather than the indigenous people claimed to be its actual audience.

A Bloody Conquest Justified

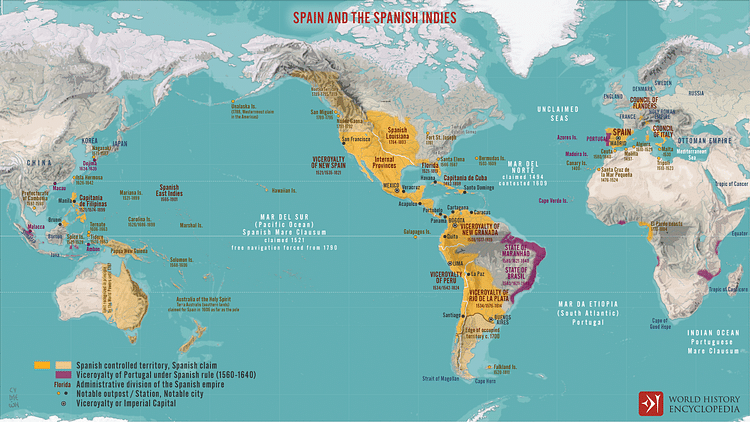

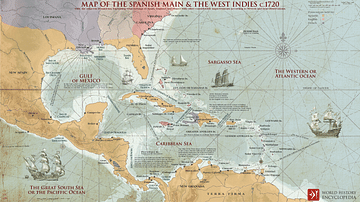

The European colonization of the Americas began in 1492 and the landing of Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506) in the Caribbean. Although Columbus and the Spanish monarchy were actually interested in finding a direct sea route to China and the spices of the East, the chance discovery of the islands of the Caribbean was exploited for all it was worth. Backed by a papal bull that justified conquest and with their rivals the Portuguese dealt with in the audacious 1484 Treaty of Tordesillas, the Spanish Crown was keen to get colonizing.

The Spanish took over Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic/Haiti) in 1494, Puerto Rico in 1508, Jamaica in 1509, and Cuba in 1511. In the spring of 1513, Juan Ponce de León (1474-1521) was the first European to make a documented landing in Florida. In the same year, Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475-1519) crossed the Isthmus of Panama and became the first European to sight the Pacific Ocean. The New World began to look like a very promising place for the newcomers.

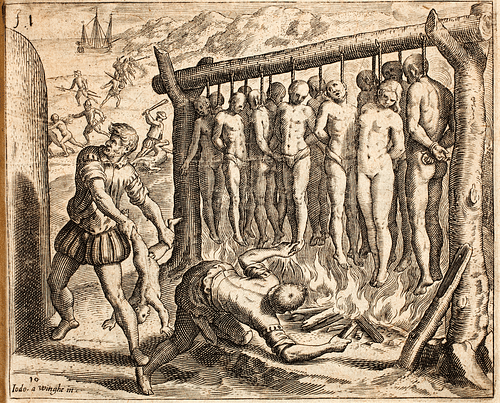

In this process of colonization, indigenous peoples were robbed, tortured for their valuables, and dispossessed of their land. Thousands were killed in warfare and resistance, many were simply murdered. Even those who survived then had to face the fatal threat of European-born diseases. The conquistadors on the ground may not have cared very much about the human cost of their adventures, but there were some voices of protest back in Spain in both the Church and the government. For many figures in higher authority, conquest was not only an opportunity to gain resources, it also brought a duty to teach indigenous peoples the fundamentals of Christianity. The official line was that native peoples who peacefully accepted the Spanish monarch as their new ultimate overlord should be given in return the opportunity to save their souls and be provided with protection from physical harm and abuse. To make these concepts clear for both conquerors and conquered, in 1513 the Spanish Crown tasked the noted jurist Juan López de Palacios Rubios with creating an extraordinary document, the Requerimiento.

The Requerimiento allowed many to ease their guilt at the tremendous destruction of conquest. Arguments like the lack of technological advancement in the cultures that were attacked, the interpretation that rulers governed only through a system of tyranny, that non-Christian rulers could not possibly hold any authority from God to rule, along with the growing evidence of the more dramatic elements of indigenous religious practices like human sacrifices and occasional cannibalism, were all held up as a justification that Spain was bringing light to a dark corner of God's kingdom. The conquest of the New World came to be viewed in a similar light to the Crusades. The Requerimiento offered the indigenous people a peaceful solution to a new political, military, and religious reality, if they chose to reject it, then the Spanish were, they thought, legally and morally justified in pursuing whatever means possible to complete their aims of conquest.

Contents

The Requerimiento consisted of around 1,000 words split into four parts as summarised here by the historian D. M. Carballo:

- The European biblical vision of cosmogenesis and partitioning of the Americas between Spain and Portugal by the papal bull and Treaty of Tordesillas.

- Spain's legitimate right to evangelize in the Americas by virtue of the first.

- A plea that native peoples submit to the king and pope.

- A promise of war and violence if they do not submit, including the enslavement of women and children.

An example passage here tells of the story of Creation and the development of different kingdoms on earth:

God our Lord, one and eternal, created the heavens and the earth, and one man and one woman, from whom we and you and all men of the world were and are descended and procreated, as well as all who should come after us. Owing to the great number which have come from them…it was necessary that some men should go to one part, and others to another, and then they should be divided in many Kingdoms and provinces, those who could not be sustained and preserved in one.

(Alan Covey, 203)

The indigenous peoples were expected to accept these peaceful overtures and the new status quo where they were now subjects of the Spanish Crown and prospective members of the Christian Church. If they did not accept these terms, then the document concluded with a series of ominous threats:

We shall make war against you in all ways and manners…and shall do all the harm and damage that we can…[and all] the deaths and losses [that result will be] your fault, and not that of Their Highnesses, nor ours, nor of these gentlemen in our company.

(Cervantes, 80)

Practicalities

Although the Requerimiento was meant to be read out on first contact or before a battle, it was often read only in Spanish and so was incomprehensible to its intended audience. The document might be read out across a battlefield when a friar or notary could be given this duty and as he would have made sure he was standing well out of range of missiles, even if the audience could have grasped its meaning, they would not have heard the words being spoken. Offering a translation of the document in the language of the people concerned was only a recommendation. Even when efforts were made to translate the document, the result was so confusing that it might as well have remained in Castilian Spanish. Communication was so ineffective that many of the conquistadors believed it was solely for their own benefit or God's that they were reading out the Requerimiento. After having listened to or read the document, the locals were then expected to sign their agreement to it.

The Requerimiento was read out to indigenous tribes across the continent for decades. At the very first reading of it, by the notary Rodrigo de Colmenares in Colombia on 19 June 1513, it was already noticed by an eyewitness that "it would seem that these natives will not listen to the theology of the Requerimiento and we have no one here who can help them understand it" (Cervantes, 80). Still the document was read out time and time again, including to such elevated figures as the Inca ruler Atahualpa (r. 1532-3) when the conquistadors first made contact with him. Hernando de Soto (c. 1500-1542) did the honours that day on 15 November 1532, but at least Atahualpa was blessed with having an interpreter on hand. The document was still being read out in the 1540s, for example, by those Spanish forces operating against the Chichimeca north of the Valley of Mexico.

When it was understood, the Requerimiento was often rejected out of hand by native leaders who could see no reason to give up their powers, wealth, and way of life to these intruders, at least not without a fight. While some indigenous leaders were more wily, pretending to agree to the declaration but then blithely ignoring it, some were more openly defiant. The Maya at Chichen Itza in 1532 famously responded to the reading out of the Requerimiento with the following: "We already have kings oh noble lords! Foreign warriors, we are the Itza!" (Thomas, 199)

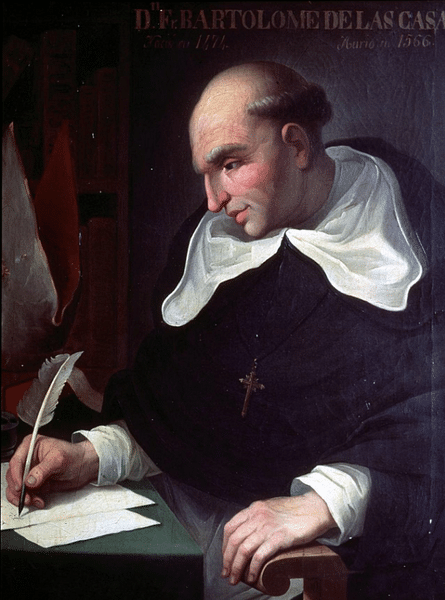

There were voices of protest in Spain and in the colonies by those who recognised the Requerimiento for the charade it was. The noted Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484-1566) once reported that he did not know whether to laugh or cry upon hearing the full Requerimiento statement. Las Casas described the document as "unjust, impious, scandalous, irrational, and absurd" (Cervantes, 81).

Besides the obvious arguments that the whole affair was unrealistic and impractical, there were those who questioned its legality and the absurd presumption and keystone of the document that 'the World' was the same as 'Christendom'. There was, too, a debate as to how far one could carry papal authority to convert non-believers and just what means, military or otherwise, justified the ends of converting them. Distinguished voices such as that of the Dominican jurist Francisco de Vittoria argued that foreign princes had just as much right to rule their people as the Holy Roman Emperor did to rule his. These arguments, although they continued through the 16th century, were largely academic, though, and had little effect on the participants on either side of the conquest in the New World itself. The Requerimiento remained, as the historian F. Cervantes puts it, "a confection of religious idealism and naked self-interest" (80).