Magic was an integral aspect of life in ancient Egypt. The world was created through the power of heka (magic) as Atum stood on the primordial mound of the ben-ben in the middle of the endless waters of chaos with the god Heka, who personified magical power. It was Heka who allowed for the gods to perform their duties through heka and, most importantly, maintained the concept of ma'at, harmony and balance in the universe.

When one became sick and consulted a doctor, the prescription and rituals used to heal involved magical spells. Magic was invoked in the hope of a woman becoming pregnant, throughout her term, and at the birth of the child when the Seven Hathors were thought to appear to divine the infant's destiny. Throughout one's life this same belief persisted, and at death, it was magical charms, rituals, and incantations which assured the soul of easy passage to eternal life in the paradise of the Field of Reeds. Magic also factored in one's afterlife through the spells provided in The Book of Coming Forth by Day, better known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead.

While many of these supernatural initiatives invoked the blessings of the gods, their primary purpose was to ward off evil spirits or to appease the gods in case one had angered them. An ancient Egyptian also had to be aware of the presence of angry ghosts and, of course, of living humans who meant them harm. To maintain one's health and safety, therefore, rituals and incantations were used which are now known as the Execration Texts.

'Execration' means to denounce or curse a person, entity, or object one finds detestable, dangerous, or offensive in some way. These texts were not only curses but specific formulae designed to ward off or destroy harmful entities before they had a chance to harm someone or, in the case of physical or mental illness, to drive the evil spirit out and banish it from returning.

Execration texts, therefore, are the earliest known form of exorcism and were used regularly. Over one thousand of these ritual texts have been excavated thus far in Egypt. The best-known execration texts in the modern day are the famous curses inscribed on tombs warning of punishment for any who entered the tomb unwelcomed or unpurified. The famous 'Curse of Tutankhamun' also known as 'the mummy's curse', well known from Hollywood movies, is the best example of an execration text.

Origin & Development

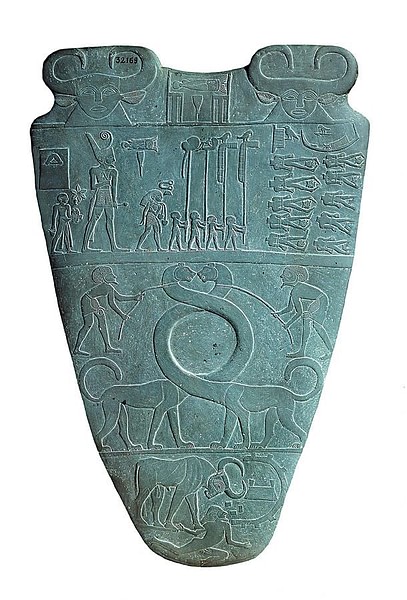

The execration texts date from the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) and continue through to Roman Egypt; almost the entirety of ancient Egypt's history. The practice of ritually slaying one's enemies through some sort of ceremony, however, dates to the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) as suggested by various inscriptions. A scene on the famous Narmer Palette (c. 3150 BCE) showing decapitated enemy soldiers has been interpreted by some scholars as evidence of an execration ritual in which a small number of one's enemies are depicted in defeat to denote the much larger numbers which would be destroyed through the same magic. Egyptologist David P. Silverman explains:

If the blessed dead became the recipients of cult and correspondence, less favoured spirits were widely feared for their potential destructive wrath. Medical spells frequently cite the unholy dead as the enemy afflicting the patients, the source of illness and disease. As is evident from the "Letters to the Dead", even favoured spirits might inflict injury when angered and petitioners were quick to beg for leniency and favour. Threatening to all - both pharaoh and commoner alike - the danger that these malignant spirits posed required some form of response, and a series of rituals was devised for their suppression. (144)

These rituals took the form of a written text and corresponding action which diminished the power of one's adversary while increasing one's own. An example of this is the Magical Lullaby in which a mother or caregiver would recite prescribed words to ward off evil spirits but, it is thought, also had the herbs and vegetables on hand in the room - such as garlic hanging by an entrance - to keep such spirits at bay.

Execration rituals, from the earliest to the latest, were enacted by writing the curse or incantation on a red pot and then smashing it. The color red symbolized both danger and vitality and was often used by scribes in their texts to denote a particularly menacing deity such as Set. The Magical Lullaby does not follow this pattern completely, however, as it was more of a charm of protection than an offensive attack.

These rituals seem to have been used against natural and supernatural enemies from the beginning but, during the Old Kingdom of Egypt, increasingly took on more and more significance in protecting one's self from unseen, mystical forces. The Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom contain execration spells to help the soul of the departed avoid evil spirits in the afterlife and Text 214 gives an execration ritual to ward off evil prior to purification rites. By the time of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE), the ritual concerning the supernatural snake Apophis was practiced.

Overthrowing Apophis

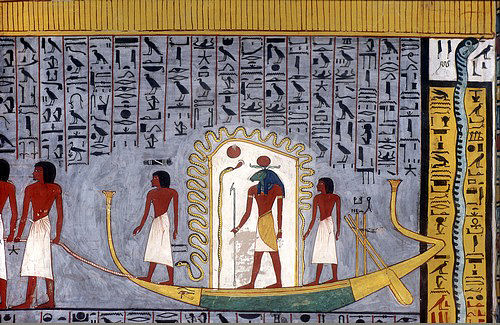

Apophis was the great serpent who attacked the barge of the sun god every night as it traveled through the underworld. The snake was thought to have either existed in the waters of chaos before creation or to have been born of the saliva of the goddess Neith when she first stepped out of those waters onto the ben-ben. Apophis represented the unified, undifferentiated world of chaos before order was instituted by the gods. Once creation was initiated the primordial oneness of existence was broken into duality: male and female, light and dark, day and night. The goal of Apophis was to destroy the sun god, the giver of light and life, and return everything to its original state.

Many of the most important and powerful gods, as well as the justified dead, sailed on the sun god's barge specifically to help protect him from Apophis in the underworld. Even the god Set, usually considered a force of chaotic destruction and often associated with Apophis, is seen aboard the ship driving the beast away. Each night the gods battled Apophis and were victorious - the snake was killed and cut into pieces - but throughout the next day he would regenerate and attack again that night.

This story first appears in texts from the Middle Kingdom, in which Apophis is first named, but ceremonies concerning him were no doubt observed earlier and became more numerous in the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-1069 BCE). At this time the execration text, The Book of Overthrowing Apophis, was written down and observed regularly. Participants would make wax figures of the serpent which would then be hacked into pieces, spit on, sometimes urinated on, and burned. By participating in this ritual, the living were helping the gods in their struggle against the serpent, were associating themselves with the justified dead, and were making sure that the sun would rise again the next morning.

Personal Defense & State Rituals

A text like The Book of Overthrowing Apophis linked one to the community, the gods, the dead, and the natural world and elevated the individual to an integral aspect of the functioning of the universe. The Magical Lullaby kept the forces of evil at bay and guaranteed the safety of one's children. Medical texts called upon more powerful supernatural forces to defeat and drive away those which were attacking a patient. There were many other kinds of texts, however, which were for one's personal use against private and public enemies. By the time of the New Kingdom, state rituals were common in which execration texts were used to empower the pharaoh. Silverman describes the process:

Although the texts and rituals described by these texts vary widely, the standard pattern of the exorcsim is clear: a 'rebellion formula' listing the names of Egypt's potential enemies is inscribed on a series of red pots or figurines, which are subsequently broken, incinerated, and buried. Although this is obviously a state ritual, there seems to have been some local input on textual choices. Most sections of the formula list the names of living rulers of lands neighboring Egypt, based on information that was surely provided by the royal chancellery. To these sections, however, is appended a list of Egyptians, all qualified as 'dead', who also pose a threat. (145)

The destruction of a person's name, image, or both was the most effective means of neutralizing their power because one was erasing them from history. Individuality and one's personal story were vitally important to the ancient Egyptians. One needed to be remembered in order to continue to exist. Food and drink offerings were an important part of the mortuary rituals for this very reason: family members would have to remember the deceased every time they brought these offerings to the tomb. In an execration ritual, one was destroying the elements of one's enemy which gave that person power and substance: their name and their likeness. State rituals were enacted to punish subversives and traitors and to lessen the power of Egypt's enemies, but individuals used the same kind of formula in their private lives.

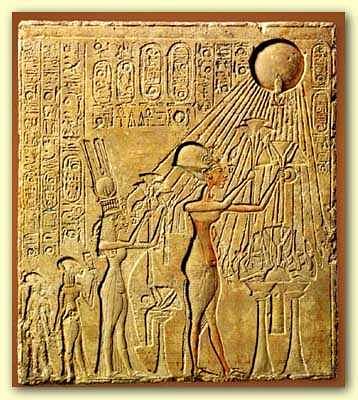

In protecting one's self against the threat of an angry ghost, for example, one would find that ghost's tomb and deface it, erasing the name and image, and would then perform a further ritual involving a written text on a red pot which was then smashed. Execration rituals were also performed, in this same way, by nobility against political enemies. The so-called 'heretic king' Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) was erased from history by the last king of the 18th Dynasty Horemheb (1320-1292 BCE) for his attempt at abolishing the traditional religion of Egypt and instituting his own brand of monotheism.

Another royal example of the execration ritual is the disappearance of queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) after her death. Hatshepsut was one of the most successful and effective monarchs in Egyptian history, but shortly after she died, her monuments were defaced and her name erased from inscriptions. It has been suggested that this was done by her successor and stepson Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE) who may have considered it impious for a woman to have reigned as a man. Her name would have been erased in order to prevent other women from following her example. Women had ruled Egypt prior to Hatshepsut, however, so there may have been some other reasoning at work. Thutmose III does not seem to have borne his stepmother any animosity and left her name untouched in temples and inscriptions which were out of the public eye.

Erased from Time

Execration texts dealing with spiritual forces are by far the most numerous. People could write to their dead friends and relatives any time they wished and these messages would be delivered to the tomb with the food and drink offerings. The letters to the dead often include flattery or even threats in trying to persuade the departed soul to help with some problem, but if this did not work, one would resort to the execration ritual.

As in the case of Akhenaten, one would attempt to completely blot the person's name from history. The final purpose was nothing less than erasing an individual from existence both in this world and the next. Without a name or likeness for people to remember there was no way one could continue to live. If one found one's self afflicted by a supernatural force and could identify it as the ghost of someone one had known, one could take care of the problem by destroying the essence of one's enemy.

In addition to the text written on the red pot, execration figurines were made. These are similar to the famous Voodoo Doll in purpose. A clay figure was made in the likeness of one's adversary, their name was written on it, and then it was stabbed using a knife or nails, spit on, urinated on, smashed, burned, and buried. Some of these figurines have been found in cemeteries where they were only stabbed multiple times and then buried or show signs of having their arms and legs hacked off prior to burial. Following such a ritual, the participant or participants could expect an end to their troubles because their enemy not only no longer existed but, in the memory of the gods, never had; they were erased from time and eternity.

Execration rituals may seem familiar to modern readers because they are still in use around the world. People regularly engage in similar rites when a romantic relationship ends badly. These rituals now go by many different names formally or informally but all involve destroying the gifts, property, or likeness of the person who caused the end of the relationship. Burning of pictures, letters, and souvenirs of the past is central to these rituals which allow one to let go of the failed relationship and move on. This would have been the same psychological benefit the execration texts provided in ancient Egypt. Whether an enemy's soul was truly erased or not, the person who enacted the ritual believed they had triumphed over their adversary and this belief alone would have gone far in alleviating whatever injustice or hurt they had been suffering from.