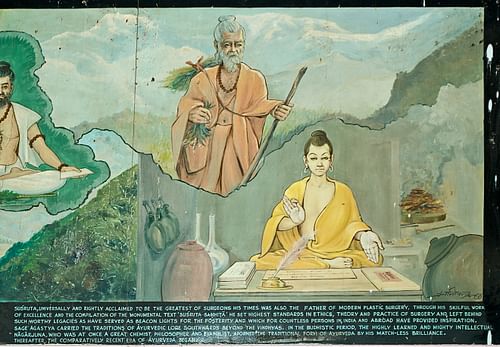

Sushruta (c. 7th or 6th century BCE) was a physician in ancient India known today as the “Father of Indian Medicine” and “Father of Plastic Surgery” for inventing and developing surgical procedures. His work on the subject, the Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta's Compendium) is considered the oldest text in the world on plastic surgery and is highly regarded as one of the Great Trilogy of Ayurvedic Medicine; the other two being the Charaka Samhita, which preceded it, and the Astanga Hridaya, which followed it.

Ayurvedic Medicine is among the oldest medical systems in the world, dating back to the Vedic Period of India (c. 5000 BCE). The term Ayurveda translates as “life knowledge” or “life science” and is the practice of holistic healing which incorporates “standard” medical knowledge with spiritual concepts and herbal remedies in treatment as well as prevention of diseases. It was practiced in India for centuries before the Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460 - c. 379 BCE), known as the Father of Medicine, was even born.

The Great Trilogy of Ayurvedic Medicine describes surgical procedures, diagnostic techniques, and treatments for various illnesses and injuries and even provides instructions for physicians on determining how long a patient will live (in the Charaka Samhita). The work of Sushruta standardized and established earlier knowledge through careful descriptions of how a physician should practice the art as well as specific procedures including performing plastic surgery reconstructions and the removal of cataracts.

The Astanga Hridaya combines the works of Charaka (c. 7th or 6th century BCE) and Sushruta, presenting a comprehensive text on both surgical and medical approaches to treatment, while also offering its own unique perspective. Sushruta's work, however, offers the greatest insight into the medical arts of the three owing to the commentary he provides in-between or included in discussions of various ailments and treatment.

Sushruta the Physician

Little is known of Sushruta's life as his work focuses on the application of medical techniques and does not include any details on who he was or where he came from. Even his birth-name is unknown as “Sushruta” is an epithet meaning “renowned”. He is usually dated to the 7th or 6th centuries BCE but could have lived and worked as early as 1000 BCE; although that seems unlikely as Charaka lived shortly before him or was a contemporary. He has been associated with the Sushruta mentioned in the Mahabharata, the son of the sage Visvamitra, but this claim is not accepted by most scholars.

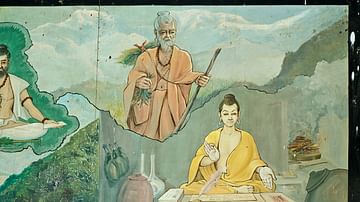

All that is known for certain about him is that he practiced medicine in northern India around the region of modern-day Varanasi (Benares) by the banks of the Ganges River. He was regarded as a great healer and sage whose gifts were thought to have been given by the gods. According to legend, the gods passed their medical insight down to the sage Dhanvantari who taught it to his follower Divodasa, who then instructed Sushruta.

The practice of surgery was already long established in India by the time of Sushruta but in a less-advanced form than what he practiced. He significantly developed different surgical techniques (such as using the head of an ant to sew sutures) and, most notably, invented the practice of cosmetic surgery. His specialty was rhinoplasty, the reconstruction of the nose, and his book instructs others on exactly how a surgeon should proceed:

The portion of the nose to be covered should be first measured with a leaf. Then a piece of skin of the required size should be dissected from the living skin of the cheek and turned back to cover the nose keeping a small pedicle attached to the cheek. The part of the nose to which the skin is to be attached should be made raw by cutting the nasal stump with a knife. The physician then should place the skin on the nose and stitch the two parts swiftly, keeping the skin properly elevated by inserting two tubes of eranda (the castor-oil plant) in the position of the nostrils so that the new nose gets proper shape. The skin thus properly adjusted, it should then be sprinkled with a powder of liquorice, red sandal-wood, and barberry plant. Finally, it should be covered with cotton and clean sesame oil should be constantly applied. When the skin has united and granulated, if the nose is too short or too long, the middle of the flap should be divided and an endeavor made to enlarge or shorten it. (Sushruta Samhita, I.16)

Wine was used as an anesthetic and patients were encouraged to drink heavily before a procedure. When the patient was drunk to a point of insensibility, he or she was tied to a low-lying wooden table to prevent movement and the operation would begin with the surgeon sitting on a stool and tools on a nearby table. The use of wine led to the development of an anesthetic involving both alcohol and cannabis incense to either induce sleep or dull the senses to a stupor during procedures such as rhinoplasty.

Rhinoplasty was an especially important development in India because of the long-standing tradition of rhinotomy (amputation of the nose) as a form of punishment. Convicted criminals would often have their noses amputated to mark them as untrustworthy, but amputation was also frequently practiced on women accused of adultery – even if they were not proven guilty. Once branded in this fashion, an individual had to live with the stigma for the rest of his or her life. Reconstructive surgery, therefore, offered a hope of redemption and normalcy.

Sushruta attracted a number of disciples who were known as Saushrutas and were required to study for six years before they even began hands-on training in surgery. They began their studies by taking an oath to devote themselves to healing and to do no harm to others; very like the later Hippocratic Oath from Greece, which is still recited by doctors in the present day. After the students had been accepted by Sushruta, he would instruct them in surgical procedures by having them practice cutting on vegetables or dead animals to perfect the length and depth of an incision. Once students had proven themselves capable with vegetation, animal corpses, or with soft or rotting wood – and had carefully observed actual procedures on patients – they were then allowed to perform their own surgeries.

These students were trained by their master in every aspect of the medical arts, including anatomy. Since there was no prohibition on dissection of corpses, as there was in Europe for centuries, physicians could work on the dead in order to better understand how to help the living. Sushruta suggests placing the corpse in a cage (to protect it from animals) and immersing it in cold water, such as a running river or stream, and then checking on its decomposition in order to study the layers of the skin, musculature, and finally the arrangement of the internal organs and skeleton. As the body decomposed and became soft, the physician could learn a great deal about how each aspect functioned and how one could help a patient live a healthier life.

Sushruta on Medicine & Physicians

Sushruta wrote the Sushruta Samhita as an instruction manual for physicians to treat their patients holistically. Disease, he claimed (following the precepts of Charaka), was caused by imbalance in the body, and it was the physician's duty to help others maintain balance or to restore it if it had been lost. To this end, anyone who was engaged in the practice of medicine had to be balanced themselves. Sushruta describes the ideal medical practitioner, focusing on a nurse, in this way:

That person alone is fit to nurse, or to attend the bedside of a patient, who is cool-headed and pleasant in his demeanor, does not speak ill of anyone, is strong and attentive to the requirements of the sick, and strictly and indefatigably follows the instructions of the physician. (I.34)

The physician's instructions should be followed without question because of the level of knowledge and expertise in application attained. A physician should always be focused on trying to prevent disease in the body, and this can only be accomplished if one understands how the body works in every aspect. To Sushruta, the practice of medicine was a journey of understanding for which a physician required a keen intelligence in order to recognize what was necessary for good health and how to apply that knowledge in any given situation. In one passage, he makes clear his purpose – or one of his purposes – in writing his compendium:

The science of medicine is as incomprehensible as the ocean. It cannot be fully described even in hundreds and thousands of verses. Dull people who are incapable of catching the real import of the science of reasoning would fail to acquire a proper insight into the science of medicine if dealt with elaborately in thousands of verses. The occult principles of the science of medicine, as explained in these pages, would therefore sprout and grow and bear good fruits only under the congenial heat of a medical genius. A learned and experienced medical man would therefore try to understand the occult principles herein inculcated with due caution and reference to other sciences. (XIX.15)

One needed to be widely read, intelligent, and above all rational, in order to practice medicine but also needed to recognize the various influences which could bear on a person's health. Charaka had already emphasized the importance of understanding a patient's environment and genetic markers in order to treat illness and Sushruta built upon this in encouraging his students to ask the patient questions and encourage honest answers. If a doctor could rule out environmental factors or lifestyle choices in a patient's disease, then genetics could be considered. Sushruta, like Charaka, understood that a genetically transmitted disease might have nothing to do with the health of a patient's parents but possibly with one or both grandparents.

If the disease was not genetic and had nothing to do with a patient's environment, then it was most likely caused by one's lifestyle, which had created an imbalance of the dosha (humors) of bile, phlegm, and air. Dosha were produced when the body acted on food that was eaten. A person's diet, therefore, was considered of vital importance in maintaining health, and a vegetarian diet was encouraged. Sushruta suggests asking the patient dietary questions as well as others pertaining to exercise and even one's thoughts and attitudes as these could also affect one's health.

Sushruta recognized that optimal health could only be achieved through a harmony of the mind and body. This state could be maintained through proper nutrition, exercise, and rational, uplifting thought. In certain cases, however, when the patient's imbalance was severe, surgery was considered the best course. To Sushruta, in fact, surgery was the highest good in medicine because it could produce the most positive results more quickly than other methods of treatment.

The Sushruta Samhita

The Sushruta Samhita devotes chapter after chapter to surgical techniques, listing over 300 surgical procedures and 120 surgical instruments in addition to the 1,120 diseases, injuries, conditions, and their treatments, and over 700 medicinal herbs and their application, taste, and efficacy, which are also dealt with in depth. It has been claimed by some scholars (such as Vigliani and Eaton) that surgery was a last resort in treatment as the ancients tried to avoid cutting into human bodies and explored other methods of healing far more often. Although there is some truth to parts of their claim, it does not apply to Sushruta. Surgery was not considered a last resort by Sushruta but actually the best means of alleviating suffering under certain conditions.

In a number of chapters throughout the book, a condition is described and a treatment suggested which includes details on how a physician should perform a certain surgery from start to finish. These details, in fact, are what marks the Sushruta Samhita as distinct from the earlier Charaka Samhita: Charaka established medical knowledge and practice while Sushruta developed surgical techniques and thus founded the practice known as Salya-tantra or “surgical science”.

According to the scholars S. Saraf and R. Parihar,

The ancient surgical science was known as Salya-tantra. Salya-tantra embraces all processes aiming at the removal of factors responsible for producing pain or misery to the body or mind. Salya (salya-surgical instrument) denotes broken parts of an arrow/other sharp weapons while tantra denotes maneuver. The broken parts of the arrows or similar pointed weapons were regarded as the commonest and most dangerous objects causing wounds and requiring surgical treatment.

Sushruta has described surgery under eight heads: Chedya (excision), Lekhya (scarification), Vedhya (puncturing), Esya (exploration), Ahrya (extraction), Vsraya (evacuation) and Sivya (Suturing). All the basic principles of plastic surgery like planning, precision, haemostasis and perfection find an important place in Sushruta's writings on this subject. Sushruta described various reconstructive methods or different types of defects like release of the skin for covering small defects, rotation of the flaps to make up for the partial loss and pedicle flaps for covering complete loss of skin from an area. (5)

These techniques were brought to bear on a variety of conditions ranging from plastic surgery reconstruction of the nose and cheek to hernia surgery, caesarian section birth, removal of the prostate, tooth extraction, cataract removal, treatment of wounds and internal bleeding, and many others. He further diagnosed and defined diseases of the eyes and ears, prescribed eye and ear drops, established the school of embryology, developed prosthetic limbs, and advanced knowledge of the human body through dissection and the resultant understanding of human anatomy.

His knowledge of how the body worked enabled him to heal without resorting to the supernatural explanation for disease or the use of charms or amulets in healing, but this is not to say that he discounted the power of a belief in higher powers. His commentaries throughout the book make clear that a physician should be aware of, and make use of, every facet of the human condition in order to treat a patient and maintain optimal health.

Conclusion

The Sushruta Samhita touches upon virtually every aspect of the medical arts but was unknown outside of India until around the 8th century CE when it was translated into Arabic by the Caliph Mansur (c. 753-774 CE). Even then, however, the text was unknown in the West until the late 19th century CE when the so-called Bower Manuscript was discovered which mentions Sushruta by name in a list of sages and also includes a version of the Charaka Samhita.

The Bower Manuscript is named for Hamilton Bower, the English army officer who purchased it in 1890 CE, and dates to between the 4th and 6th centuries CE. The existence of this text, written in Sanskrit on birch bark, suggests there may have been others – possibly many – which preserved the writings of Sushruta and other medical sages like him. Even before the discovery of the Bower Manuscript, however, British officials and soldiers in India in the 19th century CE had written home about startling surgical procedures, especially those of cosmetic surgery reconstruction, they had witnessed in the country. Their descriptions of these surgeries correspond closely with Sushruta's instructions in his compendium.

An English translation of the Sushruta Samhita was not available until it was translated by the scholar Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna in three volumes between 1907 and 1916 CE. By this time, of course, the world at large had accepted Hippocrates as the Father of Medicine and, further, Bhishagratna's translation did not receive the kind of international attention it deserved. Sushruta's name remained relatively unknown until fairly recently, as Ayurvedic medical practices have become more widely accepted, and he has begun to receive recognition for his enormous contribution to the field of medicine generally and surgical practice specifically.

Sushruta's holistic view of healing, with an emphasis on the whole patient and not just on the symptoms presented, should be familiar to anyone in the modern day. Physicians today work up a medical history of a patient based on questions asked, research possible genetic causes for a problem, and prescribe treatments ranging from medical to surgical to so-called “alternative” practices. Further, a physician's bedside manner in the modern day is considered important in establishing trust and encouraging the success of treatment. These practices and policies are considered innovations when compared with those as recent as the mid-20th century CE, but Sushruta had already implemented them over 2,000 years ago.