Walpurgis Night (30 April, annually) is a modern-day European and Scandinavian festival derived from the merging of the ancient pagan celebration of Beltane with the commemoration of the canonization of the Christian Saint Walpurga (l. c. 710 - c. 777). The event focuses on renewal, rebirth, and letting go of dark energies from the past year.

The ancient Celtic Sabbat (religious festival) of Beltane, which had merged with Germanic May Day, was Christianized at some point after 870 to celebrate the canonization of Walpurga (also given as Walburga and Valborg), a British Christian missionary who became famous for miraculous healing powers, especially concerning the effects of witches' spells, in Germany.

Saint Walpurga was canonized, and her relics moved from her abbey at Heidenheim to the city of Eichstatt, on 1 May 870. The date was most likely chosen to correspond to the earlier Beltane in keeping with the medieval Church's policy of rededicating pagan festivals to the worship of Christian saints and events in the Church calendar.

The festival is often referred to as “the second Halloween” by Neo-Pagans in the present day as it bears a number of similarities to the observance of Samhain (31 October) when bonfires are lighted, people gather for parties, and children go trick-or-treating. It is also recognized as a “thin time” or an “In-Between” when the veil between the living and the dead is at its thinnest and departed loved ones can return to visit the living while, at the same time, one must be on guard against malevolent supernatural forces which can do the same.

This last aspect of the modern-day celebration has its roots firmly in the Beltane festival which was a Celtic celebration of renewal. The night of 30 April was considered either the awakening of troublesome spirits in the spring or the last chance for the dark forces of the winter months to trouble the living.

The Germanic version of this celebration, the night before May Day, was known as Hexennacht (Witches Night) when witches had unusually potent powers and rituals were observed to keep them at bay, reduce their ability to cast spells, and drive them and whatever forces they unleashed away from the community.

In the present day, Walpurgis Night celebrations combine elements of the pagan Celtic and Germanic customs with the veneration of the Christian saint. Fires are lighted, people gather for parties to release the negative energies of the past year, and this continues until the next day, 1 May, which traditionally marked the beginning of the fertile time of spring. The year 2020 is the first in over 100 years that Walpurgis Night celebrations have been canceled or, at least, discouraged by government agencies due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the prohibitions against large gatherings of people which could spread the disease.

Pagan Festivals & the Church

Any description of ancient pagan festivals comes from the work of medieval Christian writers who denounced them prior to their Christianization. Even so, a number of these writers detailed the “atrocious” acts of the pagans and so unwittingly preserved them. Even without such accounts, one may still glimpse the pre-Christian aspects of many Christian festivals, including the present-day Walpurgis Night which retains a number of elements of the ancient past.

The Church's policy of Christianizing pagan holidays is well-established. Scholar Martin W. Walsh comments:

With the fall of the Roman Empire, it was in the Church's interest, in its gradual conversion of Celtic and Germanic Europe, to translate important aboriginal calendar dates into Christian terms. Pope Gregory the Great…outlines such a policy of appropriation and transmutation. It would be a mistake, however, to view this Christianization of the pagan calendar as a straightforward process, the product of a continuous, rational, campaign. Rather, we should speak of an evolving rapprochement of the two calendars, liturgical and traditional, over the early-medieval centuries, resulting in a rich mix of festival practice. (Lindahl et al., 133)

The traditional calendar of the Celts was cyclical – beginning and ending in the fall – and is referred to in the present-day as the Wheel of the Year. There is no evidence of an ancient “wheel of the year” calendar corresponding to the famous symbol in the present-day but plenty pointing to the observance of the Sabbats the modern calendar represents.

- Samhain (31 October)

- Yule (20-25 December)

- Imbolc (1-2 February)

- Ostara (20-23 March)

- Beltane (30 April-1 May)

- Litha (20-22 June)

- Lughnasadh (1 August)

- Mabon (20-23 September)

Samhain (“summer's end”) was the New Year's Day, marking the end of the season of warmth and light and the beginning of the time of darkness and cold. The festivals observed between Samhain and Beltane, apart from their religious significance, were celebrated to break up the winter months and give people something to look forward to. Beltane, however, signaled the beginning of the days of light returning in full – a promise given at Ostara (the Spring Equinox) when people celebrated rebirth and renewal – and was recognized as the coming of summer.

Beltane & May Day

In Europe, 1 May was celebrated as the beginning of spring following the tradition begun by the Romans. The festival of Floralia (festival of the goddess of fertility and flowers) was observed in ancient Rome between 27 April and 3 May and included sporting events, drinking, feasting, dancing, and various other entertainment.

In regions influenced more by the Celts, the festival of Beltane included these same diversions but with the addition of the phallic symbol of the Maypole, decked with long strands of ribbon which participants would grasp as they danced in a circle around it. The Maypole would later make its way from regions like Britain to mainland Europe (though some scholars argue for the reverse course in transmission). A May Queen would be chosen from among the young women of the village or city and crowned with a wreath of flowers representing Flora. The phallic Maypole represented one of the most vital aspects of the celebration: fertility and the renewal of life.

There were many rites enacted to protect and 'seal' a home against invisible presences but one of the most basic involved the head of the household attaching a rowan branch to the ceiling and carrying a lighted candle from the front door to the back of the house and to the four corners, in a certain set pattern, to create an invisible pattern of eight points which symbolized balance and harmony and served to ward off forces of imbalance and distress.

Other rituals included a kind of trick-or-treat activity among the younger people who would gather boughs from the woods and decorate doors and windowsills in the neighborhood; for their efforts, they were paid with eggs. These 'decorations' were not just for aesthetic purposes, however, but were thought to further ward off supernatural threats.

The festival was hardly fraught with fear, however, and these precautions were taken to ensure a merry and carefree celebration of life and renewal. Various types of strong drink were brewed for the event – Mai Bock beer, May wine, a type of mead called Sima – and a great feast prepared. In the same way that mischievous or malevolent spirits might make themselves known, the souls of the departed were also thought to return at this time – just as at Samhain – since Beltane marked the 'in-between' of the dark times of winter and the light of the summer months. Foods were prepared with these souls in mind as people prepared favorite dishes of their deceased loved ones.

The alcohol, said to be consumed in great volume, was not only to celebrate the arrival of better weather but also acted as a preventative against unwelcome supernatural guests while serving as a kind of beacon for the souls of the departed one wished to attend the event: the more people drank, the louder they became, and the sounds of the boisterous living were thought to drive away dark spirits and welcome those who would recognize, and respond to, the sounds of a grand party. Alcohol also encouraged another vital aspect of Beltane and May Day: various mating rituals, divination games regarding the identity of one's future spouse, and – especially – sexual dalliances among the young people of the community.

Saint Walpurga's Life & Celebration

This festival was still observed in Christian times when a young British nun named Walpurga came to Germany, following her brothers – Saint Willibald and Saint Winibald – both of whom would found religious communities. Walpurga was born in Devon, Britain, and her religious father died while on pilgrimage when she was eleven years old. She was educated at the Wimborne Abbey in Dorset where she took orders, lived, and taught until c. 741 when her uncle, St. Boniface (l. c. 675-754), enlisted her brothers in his missionary work in Germany and Walpurga joined them there.

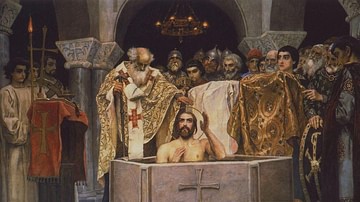

Walpurga died on 25 February 777 and was buried at Heidenheim. People continued to come to the monastery to pray at her tomb, and many reported she granted them miraculous cures from beyond the grave. In 870, her remains were removed to the town of Eichstatt and interred at the Benedictine Abbey of St. Walpurgis in the diocese founded by her brother Willibald when they had first arrived in Germany. The date given for this move and her canonization is 1 May and, although her feast day is 25 February, the Church encouraged a celebration of the saint on this date to Christianize the old pagan festivals associated with it.

Development & Modern-Day Celebrations

How, precisely, the observance of Walpurgis Night developed after it was established is unclear. Reports of miraculous occurrences continued after Walpurga's remains were transferred to Eichstatt and people would come to visit her shrine and participate in the commemoration of her canonization. This practice eventually led to the development of the modern-day festival which blended the old pagan rituals with new Christian observances such as anointing one's self with holy water and, especially, banishing witches and the bad luck of the past year; just as Walpurga is said to have been able to do.

The first known mention of S. Walpurgis Nacht (or S. Walpurgis Abend) is to be found in the Calendarium perpetuum of Johann Coler (1603). It was also mentioned in the writings of Johannes Preatorius in 1668. Translated into English, and stripped of its Catholic connotation, Saint Walpurgis Nacht becomes Walpurgis Night. (5)

By this time, the festival had merged completely with May Day and Beltane rituals and was patronized by the upper class, as Walsh describes:

Maytide was conspicuously celebrated by the landed aristocracy in outdoor fetes with boating and music, dancing about the first violet of spring, and various forms of dalliance, all celebrated by the great secular poets of the Romance and Germanic languages, the troubadours and minne-singers. Dalliance was also practiced on the commoner's level, with Lords and Ladies of the May and various nocturnal woodland jaunts. (Lindahl, et. al., 135)

These 'jaunts' Walsh alludes to were the same sexual liaisons which were such an integral part of the Beltane celebrations.

By this time, the celebration of Saint Walpurgis Night had spread from Germany to other countries. In Sweden, it was known as Valborg (as Walpurga was known there), and in Finland, it was called Vappu while the Netherlands kept the name Walpurgisnacht. In Germany, the ancient concept of 30 April as the night of witches meant that Walpurgisnacht combined, not only with Beltane but with Hexennacht and witches were burned in effigy, a practice which also spread abroad, especially to Finland. These observances, and others concerning banishing witches, were, of course, encouraged by Walpurga's famous reputation for nullifying the power of witchcraft.

The event seems to have lost some of its luster during the 18th century when there are fewer accounts of its observance, but it was revived in the 19th century by university students who seized upon Walpurgis Nacht as an occasion for drinking, dancing, mischief-making, and sexual encounters. This revival also spread from Germany to other countries (though this is disputed as Finland claims the transmission was in reverse) and developed into the modern-day celebration which some Neo-Pagans refer to as a “second Halloween”.

Some municipalities hold firework displays while others allow for controlled fires in public places. Alcohol is still central to the celebration as is the practice of making as much noise as one can and, of course, welcoming the souls of the departed whose loss one has mourned and providing them with their favorite foods.

Conclusion

Walpurgis Night has been the target of the same condemnation by conservative religious groups as Halloween has weathered over the years. The charges leveled by these critics, who usually want the event suppressed, are the same for both celebrations: that they focus on death, the macabre, and encourage destructive or unhealthy behaviors.

Those who participate in the event, however, are taking part in an ancient ritual that celebrates life and its eternal continuation, and as for the types of behavior engaged in, they are hardly any worse than what one might experience at Christmas or Easter family gatherings. If one believes that Christianity's central message is the hope of new life, renewal, and redemption, then one should have no problem with a festival which revolves around those very concepts.

In 2020, celebration of Walpurgis Night was suspended for the first time in over a century but not because of right-wing Christian complaints. The Covid-19 pandemic, requiring social distancing and quarantine to curb its spread, prevented the celebration of the festival. In the Swedish town of Lund, the authorities dumped one ton of chicken manure in the central park – where up to 30,000 residents come annually for the celebration – to deter people from gathering.

As unfortunate as actions such as this one may be, they are, rightly, considered essential in stopping the spread of a worldwide pandemic. There is little doubt, however, that the ancient festival will be celebrated again in the future, and with even greater delight and hope for better days, once the virus has become just a bad memory to be burned in effigy with any other.

![Spirit of the Witch : Religion & Spirituality in Contemporary Witchcraft (Paperback)--by Raven Grimassi [2003 Edition] ISBN: 9780738703381](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41GCV50s9XL._SL160_.jpg)