The War of the Third Coalition (1805-1806) was a major European conflict during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). It was fought by an alliance of nations that included the United Kingdom, Russia, Austria, Sweden, Naples, and Sicily, against the First French Empire of Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815), its client states, and its reluctant ally of Spain.

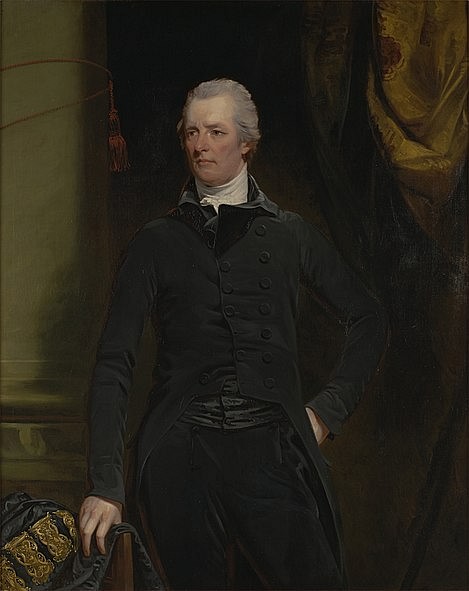

The war was born from unresolved issues left over from the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) and from a desire to check the imperial ambitions of Napoleon himself. After the breakdown of the Treaty of Amiens resulted in war between Britain and France, British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806) embarked on a diplomatic campaign to build a third anti-French coalition. Threatened by increasing French influence in Germany and Italy, and enraged by Napoleon's controversial execution of the Duke of Enghien, several European powers joined Pitt's coalition and began mobilizing their armies in August 1805; notably, Prussia opted to remain neutral.

Napoleon responded swiftly, marching his new Grande Armée into Germany, and eliminating an entire Austrian army in the Ulm Campaign (25 September to 20 October 1805). A little over a month later, he won his greatest victory yet when he defeated a Russo-Austrian army at the Battle of Austerlitz (2 December), forcing the Russians to retreat and the Austrians to sue for peace. Though Austerlitz ensured French military dominance on land, this was offset by the spectacular British naval victory at the Battle of Trafalgar (21 October), which secured Britain's mastery of the seas for the next century.

The defeat of the Third Coalition, and the death of Pitt in January 1806, was a severe blow to Napoleon's enemies. Along with reducing Habsburg power by forcing Austria to cede land and pay 40 million francs in war indemnities, Napoleon reorganized several German client states into the Confederation of the Rhine with himself as their 'Protector'. This required these states to leave the Holy Roman Empire, which resulted in the empire's dissolution in July 1806. Napoleon's newfound dominance of Central Europe alarmed Prussia, which joined France's enemies in the subsequent War of the Fourth Coalition (1806-1807).

A Shattered Peace

The Treaty of Amiens, signed between Britain and France on 25 March 1802, ended the decade-long French Revolutionary Wars. Although the war-weary people of Europe welcomed the respite from perpetual warfare, the fact that the treaty upheld most of France's revolutionary victories while forcing Britain to relinquish its recent colonial conquests all but guaranteed a resumption of hostilities. Relations between the two nations quickly deteriorated. Napoleon's acquisition of the Louisiana Territory from Spain and his decision to dispatch an expeditionary force to reclaim Saint-Domingue (Haiti) was interpreted as a challenge to Britain's colonial empire. Meanwhile, Britain provoked France by refusing to evacuate its troops from Malta, as stipulated in the treaty. After failing to diffuse the situation diplomatically, Britain declared war on 18 May 1803. The peace had lasted just 420 days.

Napoleon had not wanted another war so soon, but now that war had come, he did not hesitate to act. By the end of the month, France had occupied the Electorate of Hanover, the ancestral homeland of King George III of Great Britain. In June, Napoleon began preparations for a large-scale invasion of England. He constructed a military camp at Boulogne, which became the headquarters of a vast new army that numbered 120,000 men by March 1804. He contacted the United Irishmen to coordinate an Irish rebellion in conjunction with the French landing and made plans to gather 750 vessels to transport his army across the English Channel. To eliminate the threat of the Royal Navy, Napoleon concocted a daring plan. Two French fleets would break out of the British blockade at Brest and Toulon, cross the Atlantic, and enter the West Indies to menace the British colonies there. The British fleet would follow them into the West Indies to defend their colonies, at which point the French ships would race back to Europe to escort the army across the Channel. The plan depended on the kind of rapidity that characterized Napoleon's campaigns but was better suited for an army than a navy.

As Napoleon planned his invasion, the British also prepared for war. On 10 May 1804, William Pitt returned to the office of Prime Minister for the second time; a steadfast enemy of the French Revolution, Pitt had engineered the first two coalitions against France and wasted no time organizing a third. Other European powers were less enthusiastic; Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, even went so far as to claim, "France has done nothing to me" (Chandler, 330). However, their attitudes would quickly change in the face of growing French influence. On 18 May 1804, the French Republic became the First French Empire, with the coronation of Napoleon I occurring seven months later. In 1805, Napoleon annexed Piedmont and Elba before crowning himself as King of Italy, in direct violation of previous treaties with Austria. Napoleon also sent shockwaves throughout Europe when he violated the sovereignty of neutral Baden to kidnap and execute the Duke of Enghien, a Bourbon prince. Sweden and Russia were both horrified and cut diplomatic ties with France.

These belligerent actions drove the nations of Europe right into Pitt's arms. In December 1804, Sweden entered an alliance with Britain. The following April, Russia did as well; Tsar Alexander I of Russia felt that Napoleon's growing influence was preventing him from expanding Russian authority. By August 1805, Pitt's third Coalition had been joined by Austria, Naples, and Sicily, who all declared war with the intention of reducing France to its 1792, pre-war borders. The French Empire was joined by its client states, including its new German allies of Bavaria and Württemberg, and by Spain, which had become France's reluctant ally in 1801. Prussia decided to stay out of the war after France offered to give it Hanover in return for its neutrality.

Ulm & Austerlitz

In August 1805, the Allies devised a plan of attack. Archduke Charles was sent into northern Italy with an Austrian army of 96,000 men; the most decisive battles of the previous two coalition wars had taken place in Italy, and the Allied commanders falsely believed that this war would be won there as well. A secondary Austrian army, under General Karl Mack von Leiberich, would invade France's ally of Bavaria, where it would wait to be reinforced by a Russian army under Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov. But as Mack invaded Bavaria and encamped his army at the city of Ulm, the Russians got off to a late start. This has been blamed on the eleven-day difference between the old Julian calendar used by the Russians and the Gregorian calendar used by most of Europe. The Russians were further hindered by the poor infrastructure of Eastern Europe.

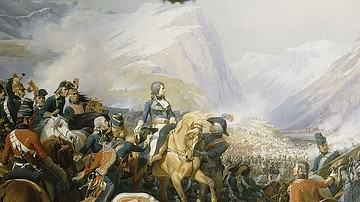

Napoleon, meanwhile, redeployed his invasion army, now numbering 210,000 men, along the Rhine. He ordered Marshal André Masséna to go to Italy with 68,000 men to distract Archduke Charles, while the rest of his army marched toward Mack; this came as a complete surprise since the Allies had not expected Napoleon to abandon his invasion of England. On 25 September, the French army – rechristened as La Grande Armée – crossed the Rhine. The Grande Armée was broken down into seven semi-autonomous corps, which were each commanded by a marshal or general and could operate independently from the main army for hours at a time. This system allowed Napoleon's army to cover more ground and move with remarkable speed; on 7 October, the French reached the banks of the Danube, only twelve days after crossing the Rhine. Mack tried to contest the French crossing of the Danube but was ultimately unsuccessful and could only watch as the French corps surrounded Ulm and trapped his army inside. With his Russian reinforcements still over 160 kilometers (100 mi) away, Mack had no choice but to surrender on 20 October 1805. After less than a month of campaigning, Napoleon had knocked an entire Allied army out of the war.

On 23 October, Kutuzov's 36,000 men finally reached Braunau. Faced with the might of Napoleon's Grande Armée, Kutuzov decided to retreat toward Moravia rather than risk a major battle, though he beat back the French in several rearguard actions. The Russian retreat left the road to Vienna wide open, and Napoleon entered the Austrian capital on 13 November. Despite his recent victories, Napoleon was in a vulnerable position. Deep in enemy territory, his army was dangerously overextended, leaving him with only 75,000 available soldiers. Meanwhile, an Allied army of 90,000 men was gathering at Olmütz (Olomouc) under the command of the emperors of Russia and Austria, and there was a chance Prussia would join the Coalition and field an additional 180,000 men. The French emperor knew he had to force a decisive battle before he was overwhelmed.

To lure the Allies into attacking him on the ground of his own choosing, Napoleon decided to feign weakness. He pulled his troops off the strategically significant Pratzen Heights and deliberately overextended his right flank, before sending an envoy into the Allied camp to ask for an armistice. The Allies fell for the ruse; convinced that Napoleon was weak, they occupied the Pratzen Heights and, on the morning of 2 December, launched the main thrust of their attack against the French right flank. This was exactly what Napoleon had wanted. His right flank was soon reinforced by Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout's III Corps, which had marched 112 kilometers (70 mi) in two days to make it to the battle on time. With most of the Allied troops engaged on the French left or right flanks, Napoleon ordered two divisions into the enemy center. Bloody fighting took place atop the heights, culminating in a climactic struggle between the French and Russian Imperial Guards. By midafternoon, the Allies were driven from the field.

After the Battle of Austerlitz (modern-day Slavkov u Brna), the Russians retreated into Hungary, while Holy Roman Emperor Francis II sued for peace. The subsequent Treaty of Pressburg (Bratislava), signed on 26 December 1805, brought Austria out of the Third Coalition, at the price of large amounts of land ceded to France's German client states and a 40-million-franc indemnity. Austerlitz would cement French military dominance on the European continent for the next decade and would be remembered as one of Napoleon's greatest battles.

Trafalgar

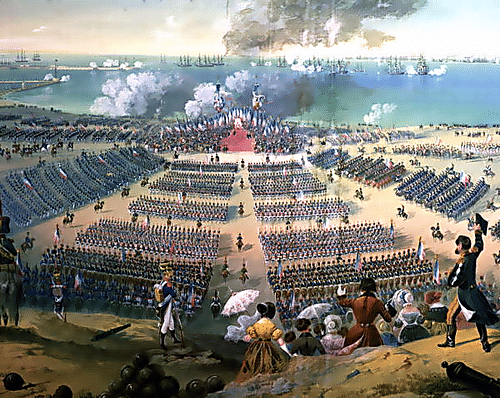

As mentioned earlier, Napoleon's planned invasion of England called for the French fleet to sail into the West Indies, thereby luring the British ships away from Europe. On 30 March 1805, French Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve saw his chance. Eluding the British blockade of Toulon, Villeneuve linked with a Spanish fleet under Admiral Don Federico Gravina at Cadiz before leading the entire Franco-Spanish fleet across the Atlantic, arriving in the West Indies in May. Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, took the bait and pursued Villeneuve to the West Indies. However, by the time Nelson arrived in June, Villeneuve was already rushed back to Europe to link with another French fleet at Brest, which would give him 58 ships with which to commence the invasion of England. Realizing he had been tricked, Nelson dispatched a frigate to London to warn the Channel fleet commanders to be on the lookout for the Franco-Spanish ships.

After his second crossing of the Atlantic, Villeneuve ran into a British fleet under Admiral Sir Robert Calder off northwestern Spain. The ensuing Battle of Cape Finisterre (22 June) was inconclusive, though Villeneuve was prevented from linking up with the French ships at Brest. Instead, he sailed for Cadiz, where he was blockaded by the British; Villeneuve's failure to make it to Brest killed any hope for the invasion of England, leading Napoleon to decide to send the Grande Armée into Germany instead. On 14 September, Napoleon sent new orders to Villeneuve, to break out of Cadiz at the first opportunity and sail to Naples, to aid the French war effort in Italy. Villeneuve was not able to sail until 20 October, when he set out in three columns southeast, toward the Straits of Gibraltar. The next day, Villeneuve was intercepted by Lord Nelson's fleet, near Cape Trafalgar.

From his flagship, the famous HMS Victory, Nelson commanded 17,000 men aboard 27 ships-of-the-line, against the Franco-Spanish fleet, which consisted of 30,000 men aboard 33 ships-of-the-line. On the morning of 21 October, as Villeneuve arranged his ships into a single battle line, Nelson chose the riskier approach of dividing his vessels into two parallel squadrons. Just before noon, Nelson hoisted the signal, "England expects that every man will do his duty," and ordered the attack (Mikaberidze, 209). The two British squadrons fell upon the Franco-Spanish line, each British warship unleashing devastating broadsides as it passed between the enemy ships. The fighting lasted for five hours but resulted in a decisive British victory. The Franco-Spanish fleet lost 17 ships captured and one destroyed. Though the British did not lose a single ship, they suffered the great loss of Lord Nelson himself, who was mortally wounded. The Battle of Trafalgar ensured Britain's mastery of the seas for the next century.

Italian Campaigns

In the autumn of 1805, when Marshal Masséna entered northern Italy at the head of 68,000 men, he was under no illusions as to the importance of his mission. His goal was to keep Archduke Charles' 96,000 Austrians detained in the Italian peninsula, to prevent them from reinforcing the Danube front. Following closely on the archduke's heels, Masséna occupied Verona and seized several key bridges over the Adige River on 17 October, hoping to provoke the Austrians into attacking. News of the calamity at Ulm made Charles hesitant to risk his army in what was now clearly a secondary theater, causing him to withdraw to Caldiero.

Charles' hesitation emboldened Masséna to attack the Austrian entrenchments; despite having a numerical disadvantage, the French fought the Austrians to a standstill at the Second Battle of Caldiero (29-30 October). On 1 November, Charles beat the French back in a series of rearguard actions as he retreated toward Venice, hoping the strength of the Austrian fortifications there would dissuade Masséna from following. He was mistaken; Masséna sent a detachment of Franco-Italian troops to blockade Venice as he continued his pursuit of Charles' army. On 14 November, the Austrians crossed the Isonzo River and set up a defensive position, but the surrender of Austria a few weeks later neutralized the threat of Charles' army.

Now, the French Army of Italy could turn its attentions south, toward Naples. In 1801, King Ferdinand IV of Naples had allied himself to Napoleon and pledged to remain neutral in the ongoing wars; he had, therefore, broken his word when he joined the Third Coalition and allowed a 13,000-man Anglo-Russian expeditionary force to land in Naples on 20 November 1805. Napoleon desired revenge, promising that the Neapolitan Bourbons would be exiled from their throne, condemned to "wander like mendicants through the different countries of Europe, begging help off their relatives" (Mikaberidze, 211). In January 1806, the Anglo-Russian force evacuated Naples, dissatisfied with the state of Neapolitan defenses.

Left to their own devices, the poorly trained Neapolitan army was no match for Masséna's 41,000 troops. Crossing the border on 8 February 1806, Masséna decisively defeated the Neapolitan army at Campo Tenese (9 March). The Bourbons fled the kingdom and Napoleon's brother, Joseph Bonaparte, was installed as King of Naples on 30 March, but the Neapolitans were unwilling to accept Joseph's administration. The region of Calabria rose in revolt and was aided by another British expeditionary force of 5,200 men; though the British defeated a French army at the Battle of Maida (4 July 1806), their victory was too late to save the Third Coalition or the Bourbons' Neapolitan throne.

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Austria was hit the hardest. It was forced to cede Venice to Napoleon's Kingdom of Italy, as well as various German territories to Napoleon's allies of Bavaria and Württemberg, both of which were elevated to the rank of kingdoms. Emperor Francis was forced to recognize Napoleon as King of Italy, Joseph Bonaparte was confirmed as King of Naples, and another of Napoleon's brothers, Louis Bonaparte, was made King of Holland.

In July 1806, Napoleon established the Confederation of the Rhine, a league of German states under the protection of the French emperor that included Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt, and several other principalities. These states were required to exit the Holy Roman Empire and provide a combined 63,000 men to Napoleon's armies. Although the Holy Roman Empire had long existed as little more than a political formality, this was the final nail in its coffin. On 12 July 1806, the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved after a thousand years of existence. Emperor Francis restyled himself as Francis I, Emperor of Austria.

In December 1805, upon learning of Napoleon's triumph at Austerlitz, Prime Minister William Pitt pointed to a map of Europe hanging on his cabinet wall. "Roll up that map," he said. "It will not be wanted these ten years" (Mikaberidze, 213). The failure of his Third Coalition had an adverse effect on Pitt's already frail health, and he died a month later on 23 January 1806. Yet the death of one of France's most stubborn foes did nothing to calm the tide of the Napoleonic Wars. Indeed, Russia, Britain, and Sweden refused to admit defeat. Joined by Prussia, they would fight on in the War of the Fourth Coalition (1806-1807).