The ancient Egyptian military is often imagined in modern films and other media as a heavily armed and disciplined fighting force equipped with powerful weapons. This depiction, however, is only true of the Egyptian army of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE) and, to a lesser extent, the army of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE), when the first professional armed force was created by Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE). Prior to this time, the army was made up of conscripts from different districts (nomes) who were enlisted by their respective governors (nomarchs). Although this early army was certainly effective enough for its purpose, it was not a group of professional soldiers equipped with the most effective weaponry. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick notes:

Soldiers of the Old and Middle Kingdoms were fairly inadequately equipped. The only development in weapons since Predynastic times had been the replacement of flint blades with those of copper. (464)

Weaponry in ancient Egypt developed in response to its necessity. The early bows, knives, and axes of the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000-c.3150 BCE) through the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) were sufficient in putting down local rebellions or conquering neighbors on the border, who were similarly armed but were not the most efficient. As Egypt expanded its influence throughout neighboring regions and came into conflict with other nations, they needed to make a number of adjustments; one of these was in weaponry.

Early Egyptian Weapons

In the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150-c.2613 BCE), military weaponry was comprised of maces, daggers, and spears. The spear had been developed by hunters during the Predynastic Period and changed very little except, like daggers, the tip changed from flint to copper. Even so, the majority of spear- and arrowheads from the Old Kingdom of Egypt seem to have been largely flint. An Egyptian soldier would have carried a spear and dagger, and a shield probably made of animal hide or woven papyrus.

These weapons were supplemented during the Old Kingdom by archers who used a simple single-arched bow with reed arrows and flint or copper tips. These bows were difficult to draw, were only effective at close range and, even then, were not very accurate. The archers, like the rest of the army, were drawn from the lower-class peasantry and would have had little experience with a bow in hunting. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson describes the Old Kingdom army:

The soldiers of the Old Kingdom were depicted as wearing skull caps and carrying clan or nome-totems. They used maces with wooden heads or pear-shaped stone heads. Bows and arrows were standard gear, with square-tipped flint arrowheads and leather quivers. Some shields, made of hides, were in use but not generally. Most of the troops were barefoot, dressed in simple kilts, or naked. (168)

Weapons, and the military in general, did not begin to develop significantly until the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. When the central government of the Old Kingdom collapsed, it initiated the era known as the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 2181- 2040 BCE) in which the individual nomarchs had more power than the king. These nomarchs would still send conscripts to the government when called upon but were free to exercise their own power and extend it beyond their districts if they wished.

This is precisely what did happen when Mentuhotep II of Thebes (c. 2061-2010 BCE) elevated his city from just another nome in Egypt to the capital of the country. Mentuhotep II defeated the ruling party at Herakleopolis c. 2040 BCE and united the country under Theban rule.

The Middle Kingdom Army

Mentuhotep II initiated the Middle Kingdom through military might, but it was Amenemhat I who organized the first professional fighting force. As in earlier eras, these soldiers were equipped with weapons sufficient for their purpose but were still far from what they would eventually become. Strudwick describes the Middle Kingdom forces:

The heavy infantry carried wood and leather shields, copper-headed spears and swords. The light infantry were armed with bows and primitive arrows made from a bronze alloy and reed shafts. Troops had neither protective helmets nor armour. (464)

Archers in this period still used the same single-arched bow and the same type of arrows, carried in a long quiver slung over the back by a strap. Daggers were copper blades riveted to handles and the sword was simply a long dagger. Since the blades were riveted to the handles, instead of the weapon being cast as a single piece, they were not as strong. One powerful blow from an opponent could snap a sword's blade from its handle.

Other weapons used at this time were the slicing axe and the spear. The slicing axe was a long wooden shaft with a crescent copper blade fitted into a notch at one end. The weapon would be wielded with two hands in a swinging motion, almost like a scythe, moving from side to side. A Middle Kingdom sword would have proved fairly ineffective against this weapon.

Although it does not seem the soldiers wore armor at this time, they did have protective gear in the form of leather shirts and kilts. These would not have afforded much protection against a volley of arrows or the slicing axe but were probably better than nothing. A typical soldier in the field would have been equipped with a sword, shield, and spear, and probably a dagger for close fighting. Archers would have naturally carried their bow and arrows and probably a dagger.

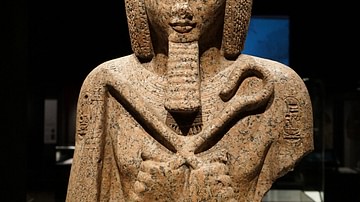

This was the army of Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE), considered the greatest king of the era and the most powerful warrior. Senusret III became the basis for the later legends of the great king Sesostris who, according to the Greek writer Diodorus Siculus, conquered the known world of his time. Senusret III, of course, did no such thing, but he did expand Egyptian territory through numerous military campaigns and ruled so effectively that his reign is largely responsible for the Middle Kingdom's enduring reputation as a 'golden age.' Even so, all of these weapons and the army itself would soon change dramatically through an event the Egyptians of the Middle Kingdom could not ever have conceived of.

The Hyksos & Egyptian Weaponry

The Middle Kingdom is considered the 'classical age' of Egyptian culture and history, but toward the end, the central government became weak and distracted by its own difficulties. A people known as the Hyksos, who had probably been trading with Egypt for some time, were allowed to gain a permanent foothold in Lower Egypt at the city of Avaris and soon were powerful enough to enforce their will through political and military measures.

Egypt had never experienced anything like the Hyksos before, and later writers would routinely refer to this time (known as the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt, c. 1782-1570 BCE) as the 'Hyksos Invasion,' a term which is still used today. There never was an invasion of the Hyksos, however, and claims to the contrary consistently focus on propaganda from the New Kingdom of Egypt or Manetho's wildly exaggerated version of events as cited in Josephus. While there was certainly armed conflict between the Hyksos and the Egyptians, there is no archaeological evidence and no solid textual evidence for the level of destruction and slaughter the New Kingdom scribes regularly ascribe to the Hyksos.

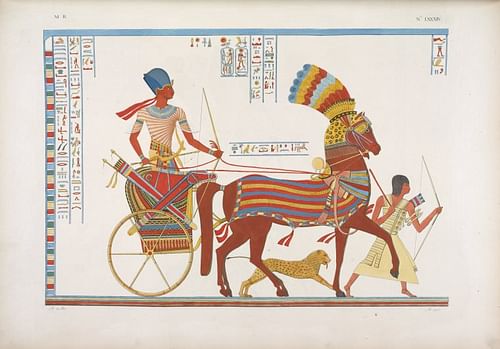

There is ample evidence, however, that the Hyksos improved Egyptian culture in a number of significant ways and, notably, through weaponry. Prior to the arrival of the Hyksos, the Egyptians had no knowledge of the horse or horse-drawn chariot, they were still using the single-arched bow and were equipped with swords which were not always reliable in pitched battle. Egyptologist Barbara Watterson describes the contributions of the Hyksos to Egyptian weaponry:

The Hyksos, being from western Asia, brought the Egyptians into contact with the peoples and the culture of that region as never before and introduced them to the horse-drawn war chariot; to a composite bow made from wood reinforced with strips of sinew and horn, a more elastic weapon with a greater range than their own simple bow; to a scimitar-shaped sword, called the Khopesh, and to a bronze dagger with a narrow blade cast in one piece with the tang. The Egyptians developed this weapon into a short sword. (60)

The Khopesh (also given as Khepesh) sword was cast entirely of bronze and the handle then wound with hide and cloth and, with more expensive blades, ornamented. This curved sword was much more effective than any the Egyptians had used in the past. The war chariot, manned by archers with the new composite bow and a large quiver attached to the side, would prove one of Egypt's most significant military assets, and the battle axe, made of bronze attached to a haft, was far more effective than the flint or copper axes bound to wooden shafts in the past. The slicing axe is probably the only weapon which Hyksos technology could not improve upon.

The New Kingdom Army

The Hyksos did far more than simply provide the Egyptians with better weapons; they gave them a reason to use them. Egypt had never been governed by a foreign power before, but during the Second Intermediate Period, the Hyksos held the ports of Lower Egypt and a significant amount of territory in the region while the Nubians had been able to expand into Upper Egypt and establish fortifications there. Only Thebes in Upper Egypt, between these two foreign powers, was ruled by Egyptians until Ahmose I of Thebes (c. 1570-1544 BCE) drove the Hyksos from the country, defeated the Nubians, and unified Egypt under his rule, initiating the New Kingdom.

Interestingly, excavations at the site of Avaris have uncovered weapons of both the Hyksos and the Egyptian forces from the assault of Ahmose I. These finds show that the Hyksos' blades had become inferior not only to the Egyptians' but to their own earlier work. It seems that, by this time, the Hyksos were making weapons largely for ceremonial, rather than practical, use. Egyptologist Janine Borriau notes:

Battle axes and daggers from stratum D/3 were of unalloyed copper, whereas weapons from earlier strata were made of tin bronze, which produced a weapon with a far superior cutting edge...In contrast, weapons of the same period from Upper Egypt were made of tin bronze and this would have given the Thebans a clear advantage in hand-to-hand fighting. (Shaw, 202)

Ahmose I used these weapons effectively against both the Hyksos and the Nubians to secure Egypt and then embarked on a campaign of conquest which his successors would continue. The monarchs of the New Kingdom were determined that never again would a foreign nation gain such power in Egypt and so expanded the country's borders to provide a buffer zone which then grew into the Egyptian Empire. The campaigns of Ahmose I through those of Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE) steadily expanded Egypt's territory, which then grew further under later pharaohs. As the army encountered new adversaries, they learned from them as Strudwick explains:

By the New Kingdom, the Egyptian army had begun to adopt the superior weapons and equipment of their enemies - the Syrians and Hittites. The triangular bow, the helmet, chain-mail tunics, and the Khepesh sword became standard issue. Equally, the quality of the bronze improved as the Egyptians experimented with different proportions of tin and copper. (466)

The weapons of the Egyptian army were now quite different from those of the Old Kingdom and so was the military itself. Bunson writes:

The army was no longer a confederation of nome levies but a first-class military force...organized into divisions, both chariot forces and infantry. Each division numbered approximately 5,000 men. These divisions carried the names of the principal deities of the nation. (170)

Unlike the early army which went to battle under the banners of their nomes and clans, the New Kingdom army fought for the welfare of the entire country, bearing the standards of the universal gods of Egypt. The king was the commander-in-chief of the armed forces with his vizier and subordinates handling the logistics and supply lines. The chariot divisions, in which the pharaoh rode, were directly under his command and divided into squadrons with their own captain. There were also mercenary forces, like the Medjay, who served as shock troops.

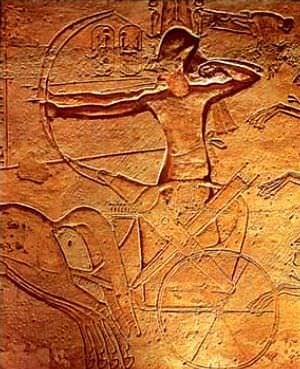

Iron Weapons & Decline

Shields in the early New Kingdom were made of wood covered with animal hide, and the swords continued to be of tin bronze until after the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE between the Egyptians under Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) and Muwatalli II (1295-1272 BCE) of the Hittites. This engagement was the campaign Ramesses II was most proud of and the victory he had announced through inscriptions, monuments, and the famous Poem of Pentaur and The Bulletin which narrate the triumph. Modern scholars have concluded that the battle was more of a draw than a victory for either side, but both the Egyptians and their Hittite adversaries claim to have won the day.

The Battle of Kadesh resulted in the world's first peace treaty in 1258 BCE between Ramesses II and Hattusili III, the successor of Muwatalli II. Egyptologist Jacobus Van Dijk explains the new relationship which was then formed between the two powers:

As a result of the peace treaty with the Hittites, specialist craftsmen sent by Egypt's former enemy were employed in the armoury workshops of Pieramesse to teach the Egyptians their latest weapons technology, including the manufacture of the much sought-after Hittite shields. (Shaw, 292)

These shields, like the Hittite swords and armor, were made of iron, and the city of Per-Ramesses became an important industrial center for the manufacture of arms as Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson describes:

State-of-the-art high-temperature furnaces were heated by blast pipes worked by bellows. As the molten metal came out, sweating laborers poured it into molds for shields and swords. In dirty, hot, and dangerous conditions, the pharaoh's people made the weapons for pharaoh's army. (313-314)

These iron weapons could not be made in great quantity, however. Forging iron required charcoal from burnt lumber, and Egypt had few trees. Egypt entered the so-called Iron Age II in c. 1000 BCE but still could not generate the number of iron weapons they needed to equip the whole army. Ramesses II's successor, Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE) would defeat the combined forces of the Libyans and Sea Peoples using the tin bronze sword as would Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) in the final battle between the Sea Peoples and Egypt.

Ramesses III is the last effective monarch of the New Kingdom. Although the Egyptian military had iron weapons by c. 1000 BCE, grand war chariots, and a professionally trained force, the army was only as effective as those who commanded. As the New Kingdom declined, the army followed suit, and even though there were brilliant monarchs who ruled in both the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Period of Ancient Egypt, they no longer, for the most part, had the resources or skill to effectively deploy the army in the field.